Siege of Buda (1849)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Siege of Buda (Hungarian: Buda ostroma) was the siege of the Buda castle, part of the twin capital cities of the Kingdom of Hungary by the Hungarian revolutionary army led by General Artúr Görgei, during the Hungarian War of Independence. It was part of the Spring Campaign, fought between 4 and 21 May 1849 and ended with the Hungarian capture of the castle by assault on 21 May. Actually it was the only fortress in the 1848-1849 Hungarian Freedom War, which was taken by the assault of the besieging troops of any of the fighting parts, the others being taken only after agreements between the besiegers and the besieged, with the capitulation of the latters, the capture of Buda on 21 May 1849 by assault being the only exception from this. The siege of Buda was also the shortest siege in the Hungarian Freedom War of 1848-1849 (18 days). With the capture of the Buda Castle ended the complete liberation of the Hungarian capital cities (Buda and Pest), and thanks to this the second Hungarian revolutionary Government led by Bertalan Szemere together with Lajos Kossuth, the Governor-President of Hungary returned from Debrecen the interim capital of the Hungarian revolution, in the real capital of Hungary. At 21 May 1849, the same day with the capture of Buda, the two emperors: Franz Joseph I of Austria and tsar Nicholas I of Russia signed the final treaty which decided the involvement of 200 000 Russian soldiers (and a 80 000 strong reserve force, in the case that they were needed) in Hungary, in order to help the Habsburg Empire to crush the Hungarian revolution.

Towards Vienna or to Buda?

After the relief of Komárom from the imperial siege, and the retreat of the Habsburg forces to the Hungarian border, the Hungarian army had two choices where to continue its advance.[2] One was Pozsony and Vienna, in order to force the enemy to fight finally on his own ground, or to return eastwards and to occupy the Buda Castle held by a strong imperial garrison of 5000 men, under the lead of Heinrich Hentzi.[2]

The first choice was supported mainly by the chief of the general staff, Lieutenant-Colonel József Bayer, and initially by Görgei, the second choices main supporter was General György Klapka, the head of the I. Corps.[3] The main reason for the first plan were, supported initially by Görgei was the threat of the Russian intervention, which the Hungarian commander hoped that his army will face with more chance of success, if they destroy the Austrian imperial army before the Tzar's troops arrival.[3]

However Görgei was quickly convinced by the supporters of the other choice: those who wanted to liberate the castle of Buda first. So he changed his mind and supported the second choice.[3] The reason was that although the first choice seemed very attractive, but it was nearly impossible to achieve a success. While the Hungarian army gathered before Komárom had less than 27 000 soldiers, the imperial army which waited them around Pozsony and Vienna was more than 50 000 strong, so it was two times bigger than Görgei's forces. Furthermore, the Hungarian army was in shortage of ammunition.[2] On the other hand the capturing of the Buda castle seemed more achievable at that moment, Klapka arguing that it is not suited for withstanding a siege, and it can be taken quickly with a surprise attack,[4] and besides it was also very important from many view-points. It could be achieved with the available Hungarian forces, a strong imperial garrison in the middle of the country could have represent a big danger if the main Hungarian army wanted to move towards Vienna, because the attacks made from the castle, would have cut the Hungarian supply lines, so it needed a Hungarian blockade with important forces in order to prevent them to come out. Also the fact that the only permanent bridge on the Hungarian part of the Danube (temporary pontoon bridges existed in many places), the Chain Bridge, was under the control of the imperial garrison of the Buda Castle, which made impossible the transport of the supplies for the Hungarian armies fighting in the West, thus this having a real strategical importance, underlined the importance of the occupation of the castle as soon as possible.[5] Furthermore the presence of Josip Jelačić's corps in Southern Hungary made the Hungarian commanders to think that the Croatian ban could advance towards Buda in any moment to relieve it, cutting Hungary in two.[2] So the Hungarian staff understood, that without taking the Buda Castle, the main army cannot make a campaign towards Vienna, without putting the country in a grave danger, and that in that moment it was impossible to achieve the victory against the numerically and technologically superior imperials gathered on the Western border of Hungary. This shows that the arguments of those historians who wrote that Görgei made a mistake by not continuing the attack towards Vienna, because he had a great chance to take the Austrian capital and win the war,[6] are wrong, and at that moment (before the arrival of the Hungarian reinforcements from the south) the only place which could bring a victory, was the Castle of Buda.

Besides the military arguments, in favor of the siege of Buda stood political ones too. The Hungarian parliament, after the declaration of the independence of Hungary, wanted to convince the foreign states to acknowledge Hungary's independence, and they knew that they have more chance of achieving this after the total liberation of their capital city Buda-Pest. And the capital city also included the Buda castle.[2] So the council of war held on 29 April 1849 decided to besiege the Buda Castle, and only after the arriving of the Hungarian reinforcements which from southern Hungary, they will start an attack against Vienna to force the empire to ask for peace and to recognize the independence of Hungary.[2]

The castle before the siege

After the ending of the Turkish occupation of Buda, in 2 September 1686, after a bloody siege of the Austrian forces, the castle was property of the Hungarian king (and in the same time Holy Roman Emperor until 1804, and after that Austrian Emperor), defended by foreign (not Hungarian nationality) soldiers led by a foreign officer.[7] After the Hungarian revolution had won, and the Batthyány Government had been formed, the castle was still defended by foreign soldiers, who had to recognize the Hungarian Government's authority. Because he did not wanted to recognize the Hungarian authority, the commander of the garrison, Lieutenant General Karl Kress, at 11 of May 1848, resigned and departed.[7] Also those foreign units stationed in the castle, who were against the Hungarian revolution, like the 23. Italian infantry regiment, who clashed in 11 June 1848 with the newly conscripted Hungarian soldiers, ending with many deaths. The 23. Italian infantry regiment after this conflict, following the order of the Hungarian War Ministry, was taken out of Hungary.[8]

Following the campaign against Hungary of the imperial armies led by Field Marshal Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, started in mid December 1848, the retreat of the Hungarian armies, and the Hungarian defeat in the Battle of Mór, on 5 January 1849 the Habsburg troops entered in the Hungarian capitals, Buda and Pest.[9] The free Hungarian parliament, the National Defense Committee (interim government of Hungary), and a big column of civilians with their goods, flee on the snowy and cold winter to East to the Tisza river installing the interim capital to Debrecen.[10] The first thing Windisch-Grätz ordered, after entering in Buda was to occupy the castle and the Gellért Hill.[9] Windisch-Grätz named Lieutenant General Ladislas Wrbna as the commander of the Buda Military District, with other words the military commander of the imperial troops from the capitals. But at the end of February, when the high commander prepared to attack the Hungarian army, he took Wrbna with him in the campaign, leaving Major General Heinrich Hentzi, the commander of the imperial garrison of the Castle of Buda, as the substitute military commander of the troops from Buda and Pest.[11]

During April 1849 the main imperial troops led by Field Marshal Windisch-Grätz suffered one defeat after another and retreated towards the Western border of Hungary. The Hungarian victory of Nagysalló on 19 April, had decisive results for the imperial occupation troops stationed in Hungary.[12] It opened the way towards Komárom, bringing its relieving to just a couple of days distance.[12] In the same time it brought the imperials in the situation of being incapable to stretch their troops on a very large front which this Hungarian victory created, so instead of uniting their troops around Pest and Buda, as they planned, Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden, the high commander of the imperial forces from Hungary, had to order the retreat from Pest being in danger to fall in the pincers of the Hungarian troops.[12] When he learned about the defeat in the morning of 20 April, he wrote to Lieutenant General Balthasar Simunich, the commander of the besieging forces of Komárom, and to Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg, the Minister-President of the Austrian Empire, that in order to secure Vienna and Pozsony, from a Hungarian attack, he is forced to retreat the imperial troops from Pest, and even from Komárom.[13] He also wrote that the spirit of the imperial troops is very low, and because of this they cannot fight another battle for a while, without suffering another defeat.[14] So the next day he ordered the evacuation of Pest, leaving an important garrison in the fortress of Buda, to defend it against the Hungarian attacks. He ordered to Jelačić to remain for a while in Pest, and than to retreat towards Eszék in Bácska where the Serbian insurgents, allied with the Austrians were in a grave situation after the victories of the Hungarian armies led by Mór Perczel and Józef Bem.[15]

On 24 April the last imperial soldiers left Pest and in the same morning 7th o'clock seven hussars, from the II. Hungarian army corps, entered in the city, being welcomed by the cheers of the happy crowds formed by the citizens, who have been waiting for so long to be liberated.[16] In the next day in Buda, Hentzi convoked two meetings with his officers, and decided that he will defend the Castle of Buda until his last breath.[17]

Preparations for the defense of Buda

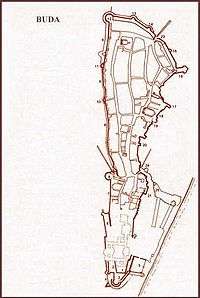

The Castle of Buda, or with other name the Upper Town of Buda (budai felsőváros) lies on a hill 167 meters above sea level, and 70 meters above the Danube, which flows under it.[18] This so called Castle Hill (Várhegy) has an oblong irregular shape of a sharp triangle with its top towards South and basis towards North. Its length is 660 meters, in its northern, wider side with the Royal Palace is 156 meters height, while in its southern edge is 163 m height and 150 m wide.[18] The castle hill is surrounded by suburbs, from East by the 260 meters wide Danube, while from the South by the 235 meters high Gellért Hill, from South-West by the 158 meters high Naphegy, also from South-West by the 168 meters high Little Gellért Hill (Kis-Gellérthegy), from West by the 249 meters high Kissváb Hill (Kissvábhegy), North-West by the 249 meters high Rókus Hill (Rókushegy or Rézmál), also from North-West by the 265 meters high Ferenc Hill (Ferenchegy or Vérhalom), also from North-West by the 161 meters high Kálvária Hill (Kálvária-hegy), from North by the 232 meters high József Hill (Józsefhegy or Sezmlőhegy), and finally also from North by the 195 meters high Rózsa Hill (Rózsadomb).[18] From East, from across the Danube there are no heights near the Castle. The height of the walls surrounding the castle were not uniform. The continuity of the walls was interrupted by old circular bastions, called rondellas, and newer, polygonal bastions, in a distance from each other which enabled to shoot on the enemy which attacked the walls between them.[19] The fact that under the walls were no moats, and except the 4 entrances to the castle, the hill was surrounded by houses, gardens and , could ease the job of the besiegers.[19] The castles defenses were on the standards of the 16th century, because the ulterior castle modernization periods had almost no effect on this castle without exterior walls and defenses, consisting only by a "core fort".[19] The most important defenses of the castle were its walls surrounding the edges of the Castle Hill. This wall was built in different periods, and in the 163 years which passed between the siege of 1686 and 1849, was repaired in different ways, and because of this it was of different widths, being without embrasures, protective structures, etc., lacking the most elementary elements of the modern siege technology.[19] The gates were mostly vestiges of the past than real castle gates, lacking trenches or drawbridges.[19] Comparing it with Hungarian castles like Arad, Temesvár, Komárom, Gyulafehérvár, Pétervárad or Eszék, it can be said that it was centuries behind of these, and because of this the intention of defending it, was surprising for many people. But the imperials understood the importance of keeping the Castle of Buda as long as they can, both of political and symbolic causes, as well because having accumulated there huge military equipment, and did not wanted to cede all of these so easily.[19]

The strengthening of the castle of Buda in the post-Revolutionary Hungary started, after the Croatian troops led by Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić entered in Hungary in order to overthrow the national Hungarian government led by Lajos Batthyány, and were advancing to the Hungarian capitals. But the first plans for this were written after Jelačić was defeated at Pákozd at 29 September 1849, and retreated from Hungary.[20] Although the enemy retreated, the fear created by it, made the Hungarians to think about strengthening Buda and Pest. They cut places of arms in the rock of the Gellért Hill.[21] At the beginning of October 1848, Artillery Lieutenant József Mack wrote in the newspaper called Kossuth Hírlapja (Kossuth's Gazette) a detailed plan to defend the capitals.[22] In this work Mack wrote that it is not true that the castle cannot be defended, writing that with the 50 cannons from the castle, they can easily hold any enemy at the distance. He wrote that only from the Gellért Hill an enemy artillery could be dangerous to the castle, but with only 6 cannons of 24 fonts he can prevent anyone to install their batteries on that hill.[23] He also wrote that the cannons can prevent also the enemy rocket batteries to burn down the city. About the necessary forces to hold the castle Mack wrote that 2500 soldiers and 300 artillerymen are enough.[23] In the Autumn of 1848 the Hungarian patriotic militiamen formed an artillery corp, and received a battery made of guns of 6 fonts.[24] In December 9 cannons and 2 howitzers arrived, which, according to an inscription which was on one of them, were made in 1559. Some of these cannons would be actually used in the defense of the castle in May 1849.[24]

With the beginning of the victorious Hungarian Spring Campaign, especially after their defeat in the Battle of Isaszeg, the imperial commanders started to be more and more concerned about the defense of the capitals and the Buda Castle. Hentzi made a defense plan of the capitals, and after this was criticized because it did not included the Buda Castle, he quickly made another one.[25] But this plan was also criticized by Colonel Trattnern, the director of the imperial military engineering, critics which proved to be right later.[26] Hentzi taught that the cannons from the 1-4th rondellas (circular bastions) need almost no protection trenches, the gates are well protected by the artillery, which can easily prevent enemy artillery to position itself before them, the circular wall of the castle is so strong, that 12 font cannons cannot damage it, so it is unnecessary to make earth revetments around it, an attack of the enemy on the Chain Bridge can easily stopped with gunfire, it is no need of shell-proof shelters, because the Hungarians have no mortars, Svábhegy is too far from the castle to be dangerous, contrary to the side of the Royal Palace, which is close to the Little Gellért Hill.[27]

In mid April, some signs showed that the imperials will retreat from Pest, like the return of the cotton bags to the inhabitants confiscated before by the commandment, in order to build defenses around the town.[28] On the other hand Welden wrote an letter to Hentzi in which he orders him to defend the Danube line, or at least the Buda castle until "the condition of the defense utilities of the castle [walls, bastions], and your food suply makes it possible".[29] The high commander drew Hentzi's attention to respond only with bullets and grapeshot against attacks and gun fire coming from the direction of Pest, and to not use cannons, in order to spare the splendid buildings of the city, allowing him to do the opposite only if the population of Pest would behave towards the imperials in an unacceptable manner.[29] But Hentzi will not respect this order, and will bombard Pest, destroying the Classicist styled buildings from the shores of the Danube, and others from Pest, despite the fact that the inhabitants of the city did nothing in order to provoke him, and the personal request of Görgei in this regard.[30] The letter informs Hentzi that the food supply of the castle is enough for 6 weeks and there is enough ammunition for the defense. It also states that the cannons to find in Buda and Pest must be brought in the castle, the waterworks which enables the defenders to be supplied with water from the Danube, must be strengthened with banqettes for cannons, the palisades from the left bank of the Danube, because they could be advantageous for the enemy, must be removed.[31]

Major General Heinrich Hentzi was (1785-1849) was an experienced officer with deep knowledge in engineering , so he was suitable for leading the technical and logistical preparations for the defense of the castle.[32] He actually started the preparations in January 1849, after he was appointed as the leader of the renovations of the castle, after he presented himself to Field Marshal Windisch-Grätz when he occupied the capitals.[32] In the winter of 1849 Hentzi conducted the building of the edifices which protected the exits of the Chain Bridge and the palisade from the left exit of the Chain Bridge and the Újépület (New Building).[32] But after finishing those, the works stopped, because they left without money.[32]

In 24 April, when the troops of Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić left the capitals for southern Hungary, Hentzi burned the pontoon bridge across the Danube, and than announced the people who lived in the castle to gather provisions of food for two months and water, and those who cannot do this, to leave.[32] In the next days, until 3d of May, Hentzi gathered enough beef cattle and other food for his soldiers, to make enough ammunition for the infantry and artillery, and to strengthen the fortifications of the castle.[32] Under his command the engineering captains Pollini and Gorini conducted the work of 200 soldiers and many people from the Swabian villages around the capitals, and many workers from the capitals to strengthen the weak points of the fortifications, paying them a salary. They also made parapets and coverings for the cannons. Hentzi also commanded the fabrication of ammunition.[32]

Hentzi commanded that the Waterworks of Buda which supplied the castle with water from Danube to be fortified with palisade both from South and North, in order to be defended by his soldiers, and a defense edifice in the currently Clark Ádám Place, in which they could hide.[33] He named a chevau-léger captain to be the leader of the firemen, and in order to prevent as it was possible a fire to break out during the siege, he commanded that the residents of the castle to remove from their attics all inflammable materials.[33] He named a detachment of pioneers to be ready to remove the grenades or bombs which could fell in houses, in order to prevent greater damages.[33]

The northern fortified waterworks stood around the pumping station allowing the observation of the Chain Bridge to prevent an attack from there. Hentzi ordered that the planks which enabled the crossing of the unfinished bridges, were removed.[34] He also ordered that on the iron beams which led to the piers of the bridge, 4 so called Rambart boxes, filled with 400 kg of cannon powder, to be put. These 4 boxes were linked by wooden tubes in which was put tinder. In order to make the explosion of the chests more destructive, big stones were put in them.[34] The southern fortified waterworks assured the defense of the aqueduct which supplied the Royal Palace with water.[34]

Hentzi positioned his troops in the castle of Buda and outside, around the Waterworks and the exit of the Chain Bridge, in the following way:

- The 3d battalion of the 5th border guard infantry regiment: the defense line which linked the barricade pointing to Víziváros (Water City), the Waterworks Fortress, and the prmenade called Ellispszis.

- The 3d battalion of the 12th (archduke Wilhelm) infantry regiment: the defense building at the exit in Buda of the Chain Bridge, the barricade at the Vízikapu (Watergate) the houses numbering 80-85., used in the defense in the Waterworks Fortress, the Royal Palace, the stairs which led to the Castle from the lower barricade, and the lower part of the Palace Garden.

- The 3d battalion of the 10th (the Ban's) infantry regiment: Bécsi kapu, the I,, II., V. and VII. bastions. The I. circular bastion with a sentinel post with a grenade thrower, and the sentinel post from under the Royal Palace, on the curtain wall, which looked towards Krisztinaváros.

- - The 1. battalion of the 23th (Ceccopieri) infantry regiment: the Palaces Gate, before the barricade at the gate at Vízikapu, at the grenade thrower from between the I. and II. circular bastions, and also little units at the Nádor-barrack, at the so called Country House (országház), at the military depot, at the town hall and at the meat factory.

- The 1. lieutenant-colonel company of the 1. (archduke John) dragoon regiment: a platoon stationed in a shed to down left from the Palace's gate, the other in the Gróf Sándor house.[35]

The two battalions from the Waterworks Fortress, together with one of the dragoon platoon, were used as vanguards outside of Buda, towards Óbuda and the vineyards of the Buda hills.[36]

Major General Hentzi, together with the 57 artillery received from Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden, and the other 28 cannons which he repaired and adjusted, before the siege he had totally 85 cannons,[36] placed on the designated strategical places, as follows:

- two 6,two 12 fonts cannons, one 10 fonts howitzer, one 18 fonts cannon on the I. rondella

- three 12 fonts cannons on the II. rondella

- one 3 and two 12 fonts cannons on the III. rondella

- one 3 and three 12 fonts cannons on the IV. rondella

- one 10 fonts howitzer on the V. bastion

- one 6, one 12, and one 18 fonts cannons on the VI. rondella

- one 6 fonts cannon on the Vienna Gate

- one 18, two 24 fonts cannons and three 10 fonts mortars on the VII. bastion

- two 12, one 18 fonts cannons and two 10 fonts howitzer on the VIII. bastion

- four 60 fonts mortars on the IX., or Fisherman's Bastion (Halászbástya))

- one 3 fonts cannon on the Watergate

- two 12 fonts cannons and three 60 fonts mortar on the X. bastion

- three 30 and three 60 fonts mortars on the front facade of the Military Depot (Hadiszertár)

- two 12 fonts cannons on the XI. bastion

- two 24 fonts cannons, two 10 fonts howitzers, two 10 fonts mortars and four 60 fonts mortars on the Upper terrace

- one 10 fonts howitzer on the Middle terrace

- three 12 fonts cannons and two 18 fonts guns on the Lower terrace

- two 3 fonts cannons in the main guard

- three 6 fonts cannons and one 7 fonts howitzer in the northern Waterworks Fortress

- four 6 fonts cannons and one 7 fonts howitzer in the southern Waterworks Fortress

- twelve wall guns on the Ellipsz[37]

In reserve remained four 3, one 18, three 12 fonts cannons and one destroyer battery[38]

Marching of the Hungarian besieging troops to Buda, and their preparations for the siege

After the relieving of Komárom in 26 April, and the decision in the war council from 29 April of the Hungarian commanders, to besiege Buda, on the next day the I. army corps, led previously by General János Damjanich, but now by General József Nagysándor, who took his excellent predecessors place, because of and accident of the latter, which made him unable to serve the Hungarian cause,[39] departed from Komárom towards Buda, following the orders given in the same day by the High Command of the Hungarian army, which ordered to all the designated troops to do so.[40] In the following days, from the Hungarian troops stationed at Komárom, the III. corps too marched to Buda, while the VII. corps went towards West, to Győr, in order to observe the movements of the imperial armies from the Western border of Hungary.[41] The II. army corps of General Lajos Aulich which troops were mainly on the Eastern banks of the Danube, also received order to move to the other bank of the Danube, as well as the division led by György Kmety, which was stationed at Esztergom, to participate in the encirclement of the Buda castle.[41] Although the main Hungarian troops moved towards Buda, but they brought no massive siege artillery with them, only the artillery used in field battles, which unfortunately could not be very effective in sieges. It seems that, the Hungarian commanders led by Görgei taught that Hentzi did not finished yet the strengthening of the castle of Buda for the siege and it can be easily occupied with a surprise attack, if they arrive there quickly.[3] So the Hungarian army corps hurried for Buda, wanting not to be slowed down by the heavy artillery. This mistake of Görgei prolonged the siege with many days, which could have been used for the preparations for the offensive in the Western front,[42] because Hentzi strengthened the castle in time, which made impossible the occupation of Buda without heavy siege artillery. The main Hungarian troops arrived on 4 May to Buda, and all gathered on the Western bank of the river around the castle, in order to start its encirclement. Only the Szekulits division of the II. army corps remained on the Eastern side.[41] The Hungarian troops positioned themselves as follows:

- The Kmety division north-east from Buda at the Danube's bank in the Víziváros quarter of Buda

- Near it, to northe-west from the castle was the III. corps led by General Károly Knezić, on the section between the Kálvária Hill and the Kissváb Hill

- Between Kissváb Hill and the Little Gellért Hill the I. corps led by General József Nagysándor was positioned

- The section between the Little Gellért Hill and the Danube was occupied by the II. corps led by General Lajos Aulich[43]

The Hungarians started to position their field artillery on the heights surrounding the castle: the Gellért Hill (one 12 fonts battery), on Naphegy, Kissváb Hill (one 12 fonts battery), Kálvária Hill (two extended batteries).[44] The most near battery to the castle was installed on Naphegy, to 600–700 meters from it.[45]

On 4 May Görgey sent a messenger, an Austrian officer who was prisoner of war, to Hentzi, to ask him to surrender, proposing him a fair captivity.[45] He argued that the castle is not suited to withstand a siege.[46] Görgey also promised not to attack the castle from the side facing Pest, but that if Hentzi would have been fire with his artillery at Pest than he would show no mercy, and after capturing the castle, he will order the execution of all the prisoners.[47] Additionally, Görgey appealed to Hentzi's supposed Magyar sympathies (Hentzi having been born in Debrecen), but Hentzi replied that his loyalty was to the Kaiser.[48] In the same response, Hentzi also argued that the castle can be defended,[47] threatening Görgey, demanding him not attack with the artillery the castle from any direction, because than he will destroy the city of Pest with a huge bombardment.[45]

Siege

Attack against the water defenses

After receiving the negative response from Hentzi, Görgei gave order to his artillery to start shooting the castle. But the defenders responded to this shooting with even greater fire, forcing the Hungarian batteries to cahnge place in order not to be destroyed.[49] This showed that momentarily the Hungarian field artillery was too weak against the imperial cannons. Another problem was that the Hungarian artillery had not enough ammunition.[49] On 6 May General József Nagysándor wrote in his report that the ammunition ended, and he is forced to stop the cannonade against the castle. He also writes that if he will not receive the rockets and grenades he asked, he would not be able to attack the aqueduct.[49] In reality these weapons were already in Pest, but being sent before on the railway via Szolnok to Pest, but they lost their trace in Pest, and found the weapons only after a week.[49]

On 4 May Görgey sent Colonel György Kmety to attack the water defenses, which were between the Castle Hill and the Danube, being the only place outside of the castle still occupied by the imperials, because letting those in the hands of the Hungarians, would have been put in danger the supplying with water the Austrian defenders.[45] Kmety's order was to burn the Waterworks, surrounded by ramparts made of piles. The Hungarian colonel led two battle hardened battalions, the 10th and the 33th, supported by two cannons of 6 fonts.[45] When arrived near the imperial defenses, Kmety's troops encountered a heavy artillery fire from side, from the Austrian units positioned on the Fisherman's Bastion and on the Joseph Bastion, and from face from the defenders of the Watergate, the entrance in the Waterworks.[45] Despite of this, the 10th battalion reached the rampart, but there the defenders unleashed on them a heavy grapeshot and fusillade, which forced them to retreat.[45] Furthermore, Kmety and many of his soldiers were injured during the mission.[45] During the retreat the battalion disintegrated, and the soldiers sought refugee in the houses nearby. Kmety repeated the attack with the 33th battalion too, but again without success.[45] In this attack Kmety lost around 100 men.[50] After this Kmety wrote a report to Görgey, declaring that the Waterworks are impossible to be taken, because the imperial cannons from the castle dominate the road to it, causing heavy losses to the attackers, preventing any success.[45]

Before the arrival of the siege artillery

The failure of the attack against the Waterworks, showed that, because of the great fire power of the imperial artillery and infantry, the castle cannot be taken by ladders, and only by piercing the walls of the castle with heavy siege artillery. This failure also made clear to Görgei that the conquest of the castle would not be an easy task, but it will necessitate a long siege, conducted with heavy siege weapons which the besieging troops lacked (they had only light cannons, used in open field battles).[45] So he wrote a letter to Richard Guyon, the commander of the fortress of Komárom, and ordered him to send siege cannons from there.[45] On 6 May General Guyon sent 5 wall piercing cannons (4 of 24 fonts, and one of 18 fonts),[45] which arrived on 9 to 10 May, but without almost no ammunition.[51] In spite of all the solicitations of Görgei, Guyon was reluctant to send the other siege cannons towards Buda, arguing that this will leave Komárom defenseless, despite the fact that in reality these weapons were not part of the weapon depot of the named fort, because they were captured some days earlier (26 April) from the imperials, in the Battle of Komárom.[52] The English born general sent the rest of the siege cannons towards Buda only after the request of Governor Lajos Kossuth.[53] While they waited for the arrival of the siege cannons from Komárom, Görgei ordered the construction of the place for the installation of a wall piercing siege battery and a field gun battery (which had the mission to cover the siege battery against enemy fire) on Nap Hegy ("Sun Hill"), one of the hills in Buda, because he considered that the I. (Fehérvár) rondella, lying in their direction, was the weakest point of the castle.[50] The field gun battery was to cover the siege battery against castle ordnance. The batteries were more or less completed by 14 May, and the ordnance installed in the early hours of the 16th.[45]

During the wait for the siege weaponry, Görgei ordered fake night attacks against the castle to keep them busy and to divert Hentzi's attention from his plans.[53] The days of 5–7 May passed with low artillery activity on both sides.[53]

The besieging army was by no means inactive in the period between 5 and 16 May. In the early hours of 5 May, Kmety’s forces again approached the water defenses, upon which Hentzi started to bombard the Water City (Víziváros), showing again that he has no consideration for the life of the civilian city dwellers, and the Hungarians withdrew.[54] On 10th, an epidemic of cholera and typhus broke out among the defenders.[51]

On the night of 10–11 May, Hentzi ordered a breakout to rescue the wounded and sick Austrians from the Víziváros hospitals. In the attack participated a border guard company and a sapper squad.[51] The first attempt was beaten back, but when the imperial troops, led by captain Schröder, tried again in greater force at 7 am, they were successful, liberating 300 sick Austrian soldiers, causing heavy losses to Kmety's troops stationed here.[51][54]

On 12 May the fights continued with minor fights, and on 13th with an artillery duel.[51]

At first, Hentzi paid no attention to the construction of the siege batteries by the Hungarians, and put all of his effort into fulfilling his pledge to fire on Pest.[45] His rage against the buildings and the population of Pest was not tempered even by the delegation of the people of Buda, who begged him to stop the destruction of Pest, saying that if he does not accept this, they will leave the castle. Hentzi replied that they can leave the castle if they will, but he threatened that he will bombard Pest with explosive and incendiary projectiles if the Hungarian army does not stop the siege. In the next day around 300 citizens left the castle of Buda.[51] Unfortunately Hentzi kept his promise and firing went on nearly every day from 4 May onwards, and became particularly intense on 9 and 13 May, resulting in the burning and destruction of the beautiful neoclassical buildings of the Al-Dunasor (Lower Danube Row).[55] The population of Pest fled from the bombardment outside the city.[51] Hentzi's attack on the civilian buildings and the population were incompatible with the war ethics, and were condemned by the Hungarian commanders. On 13th Görgei wrote a letter to the governor Kossuth, about the destruction caused by Hentzi's senseless bombardment of Pest:

Yesterday night commander Hentzi fulfilled his promise gruesomely. With well aimed shots he managed to set in several places the splendid Danube Row on fire. The fire, helped by the strong wind, spread rapidly, and reduced the most beautiful part of Pest to ashes. - It was a terrible view! The whole city was covered by a sea of flames, and the burning bombshells showered like a rain of stars, with gruesome thundering in the swirling smoke, on the poor town. It is impossible to write down this sight accurately; but I saw in this whole phenomenon the burning of the torch lit for the the funeral feast of the dying Austrian dynasty, because those, who in this country had the smallest consideration for this perfidious dynasty, the events from yesterday obliterated it forever. This is why although I bemoan, from my heart, the destruction of the capital city, this outrageous act of the enemy, which I was powerless to prevent, and which I did nothing in order to provoke it, will make me to try with all my power to avenge it by investing even more power to besiege the castle, and I feel as my most sacred duty, to liberate the capital, as soon as possible, from this monstrous enemy.[56]

In the night of 14 May, Hentzi tried to destroy the pontoon bridge from the Csepel Island by floating down the river 5 vessels destined to burn the bridge and two vessels loaded with stones in order to destroy it, but because of the lack of the sappers who had the order to accomplish this task, only one vessel was lit, before they released them on the stream.[57] But these ships floated not as were expected on the middle of the river stream, but neared the shores, being spotted by the Hungarian sappers at the Rudas Baths, who than on their boats neared them and grappled them to the shores.[57]

The real siege begins

After the arrival of the heavy siege artillery, the Hungarian army finally could win superiority over the defenders artillery, and on 16 May start the real bombardment against the castle. After the installation of the siege cannons, the Hungarian artillery positioned itself, fore an effective siege in the following way:

- one 6 fonts half battery in Pest at the Ullmann tobacco warehouse

- one 6 fonts half battery on the Margaret Island

- one 6 fonts half battery at the port for steamboats from Óbuda. This had the mission to prevent any activity of the Nádor steamboat, which was in Austrian hands

- one 6 and one 7 fonts howitzers at Bomba Square

- one 6 fonts battery on the first post of the Kálvária Hill

- some 12 fonts cannon and six 10 fonts howitzers on the second post of the Kálvária Hill

- two 60 fonts mortars at the brick manufacture from the Vienna Gate (Bécsi kapu)

- one battery of 12 and 18 fonts cannons with a furnace destined to heat the cannon balls on the Kissváb Hill

- one wall piercing battery of 24 fonts cannons at the left side of the Naphegy Hill

- some 12 and 18 fonts cannons in 16 ballasts behind a trench at the right side of the Naphegy Hill

- four 18 fonts cannons along the Calvary stations on the road to the Gellért Hill

- two 24 fonts cannon and a furnace destined to heat the cannon balls on the highest point of the Gellért Hill

- four 18 and two 60 fonts mortars on the slope of the Gellért Hill, in the direction of Rácváros

- one 10 fonts howitzer on the Gellért Hill, on the road to the Calvary

- one 10 fonts howitzer on the Gellért Hill, 200 steps downstairs, near a vineyard

- one 12 fonts battery, to left from the previous one

- two 60 fonts bomb mortars, in a scoop near to the highest Calvary station

- one 12 fonts cannon and a 10 fonts howitzer behind parapets near the Danube, at the same height of the Rudas Baths

- one 24 fonts cannon in Rácváros, at the Zizer house[58]

With these cannons, together with those which the army had before, the Hungarians finally could shot cannonballs inside the castle, disturbing continuously the defenders in their resting and the movements of their troops.[59] The siege artillery finally started its work on 16 May, shooting the walls but also the buildings within the castle reported by the spies, to be the depots and the barracks of the enemy troops. The continuous shooting started at 4 o'clock in the morning until 6 o'clock in the afternoon,[59] by next day had shot a hole in the section of wall south of the Fehérvár Rondella.[54]

On 16 May, was when Hentzi sensed that the siege was becoming critical. He understood that the main Hungarian attack will not occur against the Waterworks from East, but from the West, against the gap created by the Hungarian artillery at the Fehérvár rondella.[60] In the council made in that night, he proposed the continuation of the bombardment of Pest, but engineering captain Philipp Pollini objected, arguing that it would be better to shot against the Hungarian artillery, in order to try to destroy them. The council accepted Pollini's plan, so at 18,30 o'clock all the cannons which were withdrew before in order to protect them against the Hungarian artillery, were sent back to the walls in order to fight the Hungarian cannons.[61]

Firing continued into the evening, and one round set fire to the roof of the palace. In revenge, Hentzi fired on Pest again next day.[54]

This so enraged Görgey that he ordered his forces to execute reconnaissance in force in the early hours of 18 May, and if the action was sufficiently successful it would be converted into a full assault.[54] The I. Corps had to attack the hole in the Fehérvár Rondella, the III. Corps attacked the IV. rondella with ladders, and Kmety's division had to make a demonstration attack against the Waterworks.[59] The attack failed. Firstly, approach to the walls was hampered by a system of obstacles put in place by the castle guard. Secondly, the gap was not ready to be climbed, and the ladders brought by the soldiers were too short.[54] Görgei in his memoirs recognizes that the failure is mainly his guilt, because he did not checked before if the hole on the wall is great enough to be passable by the soldiers. He wrote that he ordered the attack rashly, because of the anger he felt about the bombardment of Pest ordered by Hentzi, wanting to punish him by the taking the castle as quick as possible.[59] The shortness of the siege ladders also contributed to the failure. The Hungarian losses as a result of this failed attack, were around 200 soldiers.[60] After the attack, Görgei asked for more ladders, which arrived a day later, at 19 May from Pest.[60]

On 18 May Hentzi tried to fill the gap created by the Hungarian artillery in the neighborhood of the Fehérvár rondella, but a downpour during the night washed away the whole barrier.[54] A battery was set up on the Fehérvár Rondella, which on 19 May succeeded in temporarily silencing two Hungarian guns on 19 May, but the gap grew ever wider,[54] to 15 fathoms wide, becoming unfillable.[61] That night, another attempt was made to block up the gap, but heavy musket and artillery fire from the Hungarian side prevented the imperial engineers from doing effective work.[54] In these fights, engineering captain Philipp Pollini, who conducted the futile works to barricade the gap, was killed by the Hungarian firing.[61]

Seeing the intensification of the Hungarian siege, and the effectiveness of the Hungarian artillery, the defenders lost their martial spirit. An Austrian fugitive told to the Hungarians, that: ... the soldiers from the castle are depressed, wanting to escape from the siege.[61]

After the failure of the assault on the night of 17–18 May, Görgey ordered a detachment consisting of few companies to harass the defenders every night until 2 am.[54] At 2 o'clock all the firing stopped. Görgei's plan was to make the defenders believe, that after 2 am. they will be safe, and can take a rest until morning.[62] Then, on 20 May, he issued the command to capture the castle.[54] On the night of 20 to 21 May, the Hungarian artillery, as usual bombarded the castle until 2 o'clock in the night, than it stopped.[63]

Final assault

The decisive assault was to start at 3 am on 21 May after every piece of ordnance had fired on the castle from every direction.

The II. Corps, led by General Lajos Aulich, attacked from the south.[64] The 3d battalion attacked the southern Palace Gardens (Palotakert), while the 2. battalion the Waterworks. The other units of the army corps remained in reserve.[63] The soldiers of II Corps had soon penetrated the castle via the large garden at the west wall. Not having ladders, they climbed the walls on each others’ backs. The attackers entered by ladders at the Ferdinand Gate and on the rubble of the destroyed wall on the east side facing the Danube. Here, the surrounded imperial soldiers soon lay down their arms.[65]

Kmety’s division had the task of capturing the Waterworks from north, sending to attack the 3d battalion and the 1. jäger company.[54]

But the main events occurred on the Northern and Western parts of the castle where the I. and the III. Hungarian Army Corps attacked.

It was the 2nd battalion of the I Corps led by General József Nagysándor, who started the attack on the Northern side, charging into the gap, while the 4th battalion attacked the terraces from the South West of the Castle Hill. The rest of the I. army corps remained in reserve.[63] The attack made little headway at first because the defenders at the gap made by the Hungarian siege cannons, were firing from the front and from the sides on them.[63] But the covering cannonade of the Hungarian artillery caused to the defenders huge losses, and thanks to this and the determination of the attackers, Col. János Máriássy, divisional commander of I Corps, managed to take two battalions against the defenders of the gap from the side, via the castle gardens, and thus assisted the main assault to get through.[66] Thus the Hungarian troops entered through the gap.[63] The first units which broke in the castle into the gap, were the 44th and 4th. Honvéd companies led by Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Driquet, and the "Don Miguel" infantry, being supported by the fire of their comrades from the 34th and 17th companies, who climbed the wall from East to the rondella, and by the 4th company who fired from down, behind their back.,[63] and pushed the defenders deeper and deeper in the inside, on the streets of Buda castle.[54] The 1. battalion charged to South, occupying the weapon depots, the other two battalions headed to the south end of the castle, attacking from behind the imperials from the Palace gardens, easing the task of the soldiers of the II. Corps to climb the walls, and enter the castle from there.[67]

The 5th battalion of the III Corps, led by General Károly Knezić, mounted an assault on the northern castle wall, the Vienna Gate and the Esztergom Rondella, climbed the Vienna Gate and the neighboring stretch and 30 soldiers fell before they managed to fight themselves on the top of the gate and to enter the castle.[66] The reserves of the III. corps waited between the Városmajor and the brick manufacture.[63] The attackers then started to advance along Úri Street and Országház Street towards the Fehérvár Gate and the Szent György Square, to help the soldiers of the I. corps, whereupon the defenders found themselves under fire from two sides: from the soldiers of the I. and the III. Hungarian corps.[63][65] At 4 o'clock am., the Italian soldiers of the Ceccopieri regiment, who fought on the Western walls of the Southern end of the Castle Hill, on the Palace's side, in the region of the Riding Hall (Lovarda) and the Stables, surrendered, and thanks to this around 500 Hungarian soldiers could enter in the Saing George Square (Szent György tér).[67] At 5 am, Gen. József Nagysándor was pleased to report to Görgey that there were nine battalions in the castle.[65]

It was at this critical point that Hentzi, hearing what is happening on Szent György Square, rushed with two border guard and another two infantry companies of the Wilhelm regiment, and stood at the head of the defenders trying to repel the Hungarians. He soon received a fatal bullet wound in his stomach, the bullet leaving his body through his rear chest.[68][69] With him received fatal wounds also captain Gorini, the commander of the Wilhelm companies and captain Schröder.[67] The wounding of the castle commander effectively meant the castle had fallen to the Hungarian army. The rest of the defenders from the Szent György Square surrendered under the command of Lieutenant Kristin.[67] However Hentzi did not dyed, after his wounding, he was transported in the hospital on the Iskola (School) Square, and was put on a bed in the office of chief medical officer Moritz Bartl.[69]

Hentzi had previously ordered the evacuation of the water defences, and the troops from there were redeployed in the castle.[68] Kmety’s troops thus secured the water defenses too. When imperial Col. Alois Alnoch von Edelstadt, in charge of the water defenses, seeing the hopelessness of the situation and observing that the Szekulics brigade from the Pest side trying to cross on the Chain Bridge towards Buda,[70] he tried to blow up the Chain Bridge, but succeeded only in blowing himself up.[68]

The last imperial troops to surrender were those in the palace,[68] so at 7 o'clock the whole Castle of Buda was liberated.[67]

General Görgei used 19 infantry battalions, 4 jäger companies and sapper units in the final attack.[63] Against the probable outbreak attempts from the castle of the imperial cavalry, he put his troops in a constant alert.[63]

The imperials lost 30 officers and 680 soldiers, from which 4 officers and 174 soldiers died because of the epidemics which broke out in the castle during the siege. 113 officers and 4091 soldiers surrendered and became prisoners of the Hungarians.[70] 248 of cannons of various types, 8221 projectiles, 931 1 (quintal) gunpowder, 5383 q saltpetre, 894 q sulfur, 276 horses, 55 766 cash Forints.[70]

The Hungarians, according to László Pusztaszeri lost 1 captain, 4 lieutenants, 15 sergeants, 20 corporals and 630 soldiers,[70] while according to Róbert Hermann 368 dead and 700 wounded (József Bayer's report), or 427 dead and 692 wounded (Lajos Asbóth's report) soldiers and officers.[65]

As the result of the senseless imperial bombardment against Pest and the fights, it burned down 40 buildings in Pest, 98 in Buda, it suffered heavy damages 61 buildings in Pest and 537 in Buda. The most affected were the Lower Danube Row neoclassical buildings, which were lost forever, and the Royal Palace of Buda.[70]

Aftermath

After the castle was taken, the wounded Hentzi was found in the hospital he was taken, by the Hungarian officer, Lieutenant János Rónay, where the Austrian commander was declared prisoner.[69] Chief medical officer Moritz Bartl told to the Hungarian officer, that Hentzi's wound is fatal, and cannot be saved. Rónay behaved kindly towards him, but when Hentzi wanted to shake hands with him, he refused, saying that he respects him as an excellent general, but he will not shake his hand, because of the bombardment of Pest. Hentzi replied that his cannons could destroy the whole Pest, but he didn't, he just shot in the buildings which he had the orders to do it.[69] As we showed before, Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden's orders to Hentzi contained nothing about the destruction of Pest, he allowing him to bombard the city from the Eastern bank of the Danube, only in exceptional situations, when the civilians would behave towards the castle in an unacceptable manner. Than Lieutenant Rónay transported Hentzi to the Hungarian headquarters, but while headed to the destination, on the Dísz Square, the people recognized Hentzi, and wanted to harm him because of what he did to Pest, and only the strong opposition of Lieutenant Rónay saved the wounded general from being lynched.[71] Arriving to the destination many Hungarian officers (Gen. József Nagysándor, Col. Lajos Asbóth, and in the end Görgei himself) visited Hentzi, behaved kindly towards him, but when they asked, what is his wish, he replied that he wants to dye. When asked why he wants this, he replied that he knows that if he will recover, Görgei will hang him, remembering the threat of the Hungarian general in his letter to him, demanding the surrender of the castle, if he will bombard Pest, or blow the Chain Bridge. Görgei indeed did not forgot his promise made in 4 May, declaring in that day to Lieutenant-Colonel Bódog Bátori Sulcz, that he will hang Hentzi in the next day if he will recover, saying that the Austrian general does not deserve to be named as hero.[71] In the evening the health condition of Hentzi became critical, and Rónay sent for a priest, but seemingly they did not found any, maybe because no priest wanted to give him the extreme unction. Hentzi died at 22 May 1 o'clock in the morning.[71] His and Col. Alnoch's bodies were put in two unpainted coffins, and sent to the graveyard, under the escort of a Huszár squad, in order to protect the bodies from the populations anger. In 1852 the emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria ordered a monument destined to Heinrich Hentzi, which in October 1918 was dismantled.[72]

The storming of Buda castle was the zenith of the Honvéd army’s glory.[68] It also yielded a substantial quantity of arms and materiel, providing a solid foundation for the following military operations. They were indeed soon to be necessary, because Welden was preparing for another attack when he heard of the fall of Buda. Hearing the fall of the Buda castle, Welden renounced to his attack plans.[68] It was now clear that Austria alone would be unable to put down the Hungarian struggle for independence. It is telling that the very day Buda was captured, Francis Joseph I finalised an agreement by which Tsar Michael I of Russia would send 200,000 soldiers to crush the Hungarian Revolution. The Emperor marked his gratitude for this friendly assistance by kissing the hand of the Tsar.[68]

Since 1992, the Hungarian Government has celebrated the last day of the battle, 21 May, as National Defence Day (Hungarian: a honvédség napja).[73]

Notes

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 32–33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hermann 2013, pp. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 338.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 340.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 341.

- ↑ Bánlaky József: A magyar nemzet hadtörténete XXI, Buda visszavétele (1849. május elejétől végéig). Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. 2001

- 1 2 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 110.

- ↑ Hermann 1996, pp. 96–97.

- 1 2 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 113.

- ↑ Hermann 1996, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 116.

- 1 2 3 Hermann 2004, pp. 243.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 301.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 291.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 124.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 128.

- 1 2 3 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 132.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 111, 177. footnote.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 111.

- 1 2 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 111, 178. footnote.

- 1 2 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 112.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 118.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 119.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 119, 202. footnote.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 120.

- 1 2 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 121, 210 footnote.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 256.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 122, 210 footnote.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 134.

- 1 2 3 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 135.

- 1 2 3 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 136.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 136–137.

- 1 2 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 137.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 138–141.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 141.

- ↑ Bóna 1987, pp. 131.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 142–143.

- 1 2 3 Hermann 2013, pp. 29.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 338–339.

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 352.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hermann 2013, pp. 30.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 352–353.

- 1 2 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 353.

- ↑ Deak, I (1998). "An Army Divided: The Loyalty Crisis of the Habsburg Officer Corps in 1848-1849". In Karsten, P. The Military and Society: A Collection of Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. p. 211.

- 1 2 3 4 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 367.

- 1 2 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 368.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 370.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 368–369.

- 1 2 3 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 369.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hermann 2013, pp. 31.

- ↑ Hermann 2013, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 370–371.

- 1 2 Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 278.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 275–276.

- 1 2 3 4 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 372.

- 1 2 3 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 373.

- 1 2 3 4 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 374.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 374–375.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 375.

- ↑ Aggházy I. 2001, pp. 317.

- 1 2 3 4 Hermann 2013, pp. 33.

- 1 2 Hermann 2013, pp. 31–33.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 376.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hermann 2013, pp. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 Hermann Róbert, Heinrich Hentzi, a budavári Leonidász, Aetas, p. 57

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 377.

- 1 2 3 Hermann Róbert, Heinrich Hentzi, a budavári Leonidász, Aetas, p. 58

- ↑ Hermann Róbert, Heinrich Hentzi, a budavári Leonidász, Aetas, p. 59

- ↑ "Jeles Napok – Május 21. A magyar honvédelem napja ("Important Days - Hungarian Defence Day")". jelesnapok.oszk.hu (in Hungarian). National Széchényi Library. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

Sources

- Aggházy, Kamil (2001), Budavár bevétele 1849-ben I-II ("The capture of the Castle of Buda in 1849") (in Hungarian), Budapest: Budapest Főváros Levéltára, ISBN 963-7323-27-9

- Bánlaky, József (2001). A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme ("The Military History of the Hungarian Nation) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Arcanum Adatbázis.

- Hermann, Róbert (2001), 1848-1849 a szabadságharc hadtörténete ("Military History of 1848-1849") (in Hungarian), Budapest: Korona, ISBN 963-9376-21-3

- Hermann, Róbert (2004). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc nagy csatái ("Great battles of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848-1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi. p. 408. ISBN 963-327-367-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (1996). Az 1848–1849 évi forradalom és szabadságharc története ("The history of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Videopont. p. 464. ISBN 963-8218-20-7.

- Hermann, Róbert. "Buda bevétele, 1849. május 21." (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on February 16, 2009.

- Hermann, Róbert (February 2013), "Heinrich Hentzi, a budavári Leonidász" (PDF), Aetas

- "Buda visszavívása". Múlt-kor történelmi portál (in Hungarian). 20 May 2004. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- "Várharcok az 1848-49-es szabadságharcban" (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on October 6, 2008.

- "Buda bevétele, 1849. május 21.". Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- Kapronczay, Károly (1998). "A szabadságharc egészségügye". Valóság ("Reality") (in Hungarian) (3): 15–23. Archived from the original on January 18, 2005. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- Zakar, Péter (1999). A magyar hadsereg tábori lelkészei 1848-49-ben. (in Hungarian). Budapest: METEM könyvek. Retrieved 27 January 2009.