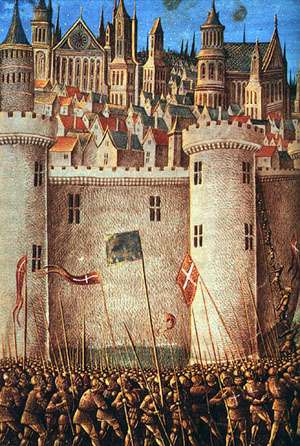

Siege of Antioch

The Siege of Antioch took place during the First Crusade in 1097 and 1098. The first siege, by the crusaders against the Muslim-held city, lasted from 21 October 1097 to 2 June 1098. Antioch lay in a strategic location on the crusaders' route to Palestine. Supplies, reinforcements and retreat could all be controlled by the city. Anticipating that it would be attacked, the Muslim governor of the city, Yaghi-Siyan, began stockpilling food and sending requests for help. The Byzantine walls surrounding the city presented a formidable obstacle to its capture, but the leaders of the crusade felt compelled to besiege Antioch anyway.

The crusaders arrived outside the city on 21 October and began the siege. The garrison sortied unsuccessfully on 29 December. After stripping the surrounding area of food, the crusaders were forced to look farther afield for supplies, opening themselves to ambush and while searching for food on 31 December, a force of 20,000 crusaders encountered a relief force led by Duqaq of Damascus heading to Antioch and defeated the army. However, supplies dwindled and in early 1098 one in seven of the crusaders was dying from starvation and people began deserting in January.

A second relief force, this time under the command of Ridwan of Aleppo, advanced towards Antioch, arriving on 9 February. Like the army of Duqaq before, it was defeated. Antioch was captured on 3 June, although the citadel remained in the hands of the Muslim defenders. Kerbogha began the second siege, against the crusaders who had occupied Antioch, which lasted from 7 June to 28 June 1098. The second siege ended when the crusaders exited the city to engage Kerbogha's army in battle and succeeded in defeating them. On seeing the Muslim army routed, the defenders remaining in the citadel surrendered.

Background

There are a number of contemporaneous sources relating to the Siege of Antioch and the First Crusade. There are four narrative accounts: those of Fulcher of Chartres, Peter Tudebode, and Raymond of Aguilers, and the anonymous Gesta Francorum. Nine letters survive relating to or from the crusading army; five of them were written while the siege was underway and another in September, not long after the city had been taken.

While there are many sources the number of people on crusade is unclear because they fluctuated regularly and many non-combatants on pilgrimage accompanied the soldiers. Historian Jonathan Riley-Smith offers a rough guide, suggesting that perhaps 43,000 people (including soldiers, armed poor, and non-combatants) were involved in the Siege of Nicaea in June 1097, while as few as 15,000 may have taken part in the Siege of Jerusalem in July 1099.[1]

Lying on the slopes of the Orontes Valley, in 1097 Antioch covered more than 3.5 square miles (9 km2) and was encircled by walls studded by 400 towers. The river ran along the city's northern wall before entering Antioch from the northwest and exiting east through the northern half of the city. Mount Silpius, crested by a citadel, was the Antioch's highest point and rose some 1,000 feet (300 m) above the valley floor. There were six gates through which the city could be entered: three along the northern wall, and one on each of the south, east, and west sides.

The valley slopes made approaching from the south, east, or west difficult, so the most practical access route for a large number of people was from the north across flatter ground. The city's defences dated from the reign of the Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century. Though Antioch changed hands twice between then and the arrival of the crusaders in 1097, each time it was the result of betrayal rather than inadequacy of the defences.[2]

After the Byzantine Empire reconquered Antioch in 969 a programme of fortification building was undertaken in the surrounding area to secure the gains. As part of this, a citadel was built on Mount Silpius in Antioch. High enough to be separate from the city below, historian Hugh Kennedy opined that it "[relied] on inaccessibility as its main defence".[3] At its fall to Seljuk Turks in 1085, Antioch was the last Byzantine fortification in Syria.[4] Yaghi-Siyan was made Governor of Antioch in 1087 and held the position when the crusaders arrived in 1097.[5]

Yaghi-Siyan was aware of the approaching crusader army as it marched through Anatolia in 1097; the city stood between the crusaders and Palestine.[6] Though under Muslim control, the majority of Antioch's inhabitants were Christians.[5] Yaghi-Siyan had previously been tolerant of the Christian populace, however that changed as the crusaders approached. To prepare for their arrival he imprisoned the Eastern Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, John the Oxite, turned St Paul's Cathedral into a stable and expelled many leading Christians from the city. Yaghi-Siyan then sent out appeals for help: his request was turned down by Ridwan of Aleppo because of personal animosity, however Yaghi-Siyan was more successful in his approaches to other nobles in the region and Duqaq of Damascus, Toghtekin, Kerbogha, the sultans of Baghdad and Persia, and the emir of Homs all agreed to send reinforcements. Meanwhile, back in Antioch Yaghi-Siyan began stockpiling supplies in anticipation of a siege.[6]

Knowing they had to capture Antioch, the crusaders considered how best to go about the task. Attrition suffered during the army's long journey across Anatolia meant the leaders considered leaving an assault until reinforcements arrived in spring. Tatikios, the Byzantine advisor to the crusade, suggested adopting tactics similar to those used by the Byzantines themselves when they moved to capture Antioch in 968. They had installed themselves at Baghras some 12 miles (19 km) away and from there conducted a blockade of the city by cutting of its lines of communication.[7] Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse, was alone in advocating assaulting the city.[8] In the end, the crusaders chose to advance on Antioch and establish a siege close to Antioch.[7]

First siege

Starting the siege

On 20 October 1097 they reached a fortified crossing, known as Iron Bridge, on the Orontes River 12 miles (19 km) outside Antioch. Robert II, Count of Flanders and Adhemar of Le Puy led the charge across the bridge, opening the way for the advancing army. Bohemond of Taranto took a vanguard along the river's south bank and headed towards Antioch on 21 October and the crusaders established themselves outside the city's north wall.[7] The crusaders divided into several groups. Bohemond camped outside Saint Paul's Gate near the northernmost corner of the city walls and immediately to the west were Hugh I, Count of Vermandois; Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy; Robert II, Count of Flanders; and Stephen II, Count of Blois. Adhemar of Le Puy and Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse, took up positions outside the Dog Gate either side of where the Orontes penetrated Antioch's defences. Godfrey of Bouillon was stationed west of the Duke's Gate in the northwest of the city walls. The bridge across the Orontes outside Antioch's west walls remained under Yaghi-Siyan's control at this point.[9] The ensuing nine-month siege has been described as "one of the great sieges of the age".[10]

The sources emphasise that a direct assault would have failed.[11] For instance Raymond of Aguilers noted that the chaplain of Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse, said "[Antioch] is so well fortified that it need not fear attack by machinery nor the assault of man, even if all mankind came together against it".[12] According to Fulcher of Chartres the leaders resolved to maintain the siege until the city was forced into submission.[11] Though his figures may not be accurate, Raymond of Aguilers gave an account of the army defending the city: "There were, furthermore, in the city two thousand of the best knights, and four or five thousand common knights and ten thousand more footmen".[13]

One of the problems of camping so close to the city was that it left the besiegers vulnerable to sorties from the garrison and even missiles. For the first fortnight of the siege the crusaders were able to forage in the surrounding area as the defenders chose not to leave the safety of the city walls,[14] however in November Yaghi-Siyan learned that the crusaders felt the city would not fall to an assault so was able to turn his attentions from the defensive to harrying the besiegers.[15] He mobilised his cavalry and began harassing the besiegers. With the immediate area stripped clean, the crusaders' foraging parties had to search further afield for supplies leaving them more vulnerable and on several occasions were attacked by the garrisons of nearby fortifications.[14] Yaghi-Siyan's men also used the Dog Bridge, outside the Dog Gate to harass the crusaders. Adhemar of Le Puy and Raymond IV's men, who were camped closest to the bridge attempted to destroy it using picks and hammers but made little impact on the strong structure while under missile fire from Antioch's defenders. Another attempt was made to render the bridge unusable, this time with a mobile shelter to protect the crusaders, but the garrison sortied and successfully drove them away. Soon after three siege engines were built opposite the Dog Gate. In the end, the crusaders erected a blockade on the bridge to obstruct potential sorties.[16]

The port of St Symeon on the Mediterranean coast, 9 miles (14 km) west of Antioch would allow the crusaders to bring reinforcements. Raymond of Aguilers mentions that the English landed at the port before the crusade reached Antioch, but did not record whether a battle for control of St Symeon took place. Reinforcements in the form of thirteen Genoese ships reached St Symeon on 17 November, and though the route from Antioch to St Symeon ran close to the city walls, meaning the garrison could impede travel, joined up with the rest of the crusaders.[17][18] According to the Genoese chronicler Caffaro di Rustico da Caschifellone, the Genoese suffered heavy casualties en route from St Symeon to Antioch.[19] Bohemond's troops built a counterfort outside Saint Paul's Gate in Antioch's northeast wall to protect themselves against missiles from Antioch's defenders. Known as Malregard, the fort was built on a hill and probably consisted of earthen ramparts. The construction has been dated to around the time the Genoese arrived.[20] The crusaders were further bolstered by the arrival of Tancred,[8] who set up camp to the west of his uncle, Bohemond.[9]

Winter

As the crusaders' food supply reached critical levels in December,[20] Godfrey fell ill. On 28 December Bohemond and Robert of Flanders took about 20,000 men and went foraging for food and plunder upstream of the Orontes. Knowing the crusaders' force had been divided, Yaghi-Siyan waited until the night of 29 December before making a sortie. He attacked Count Raymond's encampment across the river, and though caught by surprise Count Raymond was able to recover and turn Yaghi-Siyan's men back. He almost succeeded in reversing the attack entirely, forcing a way across the bridge and establishing a foothold on the other side and holding open the city gates. As the crusaders threatened to take the city, a horse lost its rider and, in the ensuing confusion in the dark, the crusaders panicked and withdrew across the bridge with the Turks in pursuit. The stalemate was restored, and both sides had suffered losses.[21]

While Count Raymond was repulsing a sally from Antioch's garrison, an army under the leadership of Duqaq of Damascas was en route to relieve Antioch. Bohemond and Robert of Flanders were unaware that their foraging party was heading towards Duqaq's men. On 30 December news reached Duqaq while his army was at Shaizar that the crusaders were nearby. On the morning of 31 December Duqaq marched towards Bohemond and Robert's army and the two met at the village of Albara. Robert was the first to encounter Duqaq's men as he was marching ahead of Bohemond. Bohemond joined the battle and with Robert fought back Duqaq's army and inflicted heavy casualties. Though they fought off Duqaq's army, which retreated to Hama, the crusaders suffered too many casualties to keep foraging and returned to Antioch.[22] As a result of the fight the crusaders lost the flock they had gathered for food[14] and returned with less food than they needed.[23] The month ended inauspiciously for both sides: there was an earthquake on 30 December, and the following weeks saw such unseasonably bad rain and cold weather that Duqaq had to return home without further engaging the crusaders.[23] The crusaders feared the rain and earthquake were signs they had lost God's favour, and to atone for their sins such as pillaging Adhemar of Le Puy ordered that a three-day fast should be observed. In any case at this time supplies were running dangerously low, and soon after one in seven men was dying of starvation.[22]

Though local Christians brought food to the crusaders they charged extortionate prices. The famine also affected the horses, and soon only 700 remained.[23] The extent to which the crusader army was affected is difficult to gauge, but according to Matthew of Edessa one in five crusaders died from starvation during the siege and the poorer members were probably worse off.[24] The famine damaged morale and some knights and soldiers began to desert in January 1098, including Peter the Hermit and William the Carpenter. On hearing of the desertion of such prominent figures, Bohemond despatched a force to bring them back. Peter was pardoned while William was berated and made to swear he would remain with the crusade.[25]

Spring

The arrival of spring in February saw the food situation improve for the crusaders.[26] That month Tatikios repeated his earlier advice to resort to a long-distance blockade but his suggestion was ignored;[26] he then left the army and returned home. Tatikios explained to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos that Bohemond had informed him that there was a plan to kill him, as they believed Alexios was secretly encouraging the Turks. Those close to Bohemond claimed that this was treachery or cowardice, reason enough to break any obligations to return Antioch to the Byzantines. News arrived that a Turkish army was approaching and Bohemond used the situation to his advantage. He declared that he would leave unless he was allowed to keep Antioch for himself when it was captured.[27] Knowing fully that Bohemond had designs on taking the city for himself, and that he had probably engineered Tatikios' departure in order to facilitate this, Godfrey and Raymond did not give in to his demands, but Bohemond gained the sympathies and cooperation of the minor knights and soldiers.

Yaghi-Siyan had reconciled with Ridwan of Allepo and the advancing army was under his command.[28] In early February news reached the besiegers that Ridwan had taken nearby Harim where he was preparing to advance on Antioch. At Bohemond's suggestion, the crusaders sent all their cavalry (numbering about 700 knights) to meet the advancing army while the infantry remained behind in case Antioch's defenders decided to attack. On the morning of 9 February, Ridwan moved towards the Iron Bridge. The crusaders had moved into position the previous night and charged the advancing army before it reached the bridge. The first charge caused few casualties, but Ridwan's army followed the crusaders to a narrow battlefield. With the river on one side and the Lake of Antioch on the other, Ridwan was unable to outflank the crusaders and exploit his superior numbers. A second charge had more impact and the Turkish army withdrew in disorder. At the same time, Yaghi-Siyan had led his garrison out of Antioch and attacked the crusader infantry. His offensive was forcing the besiegers back until the knights returned. Realising Ridwan had been defeated, Yaghi-Siyan retreated inside the city. As Ridwan's army passed through Harim panic spread to the garrison he had installed there and they abandoned the town, which was retaken by the Christians.[29]

According to Orderic Vitalis an English fleet led by Edgar Atheling, the exiled King of England, arrived at St Symeon on 4 March carrying supplies from the Byzantines. Historian Steven Runciman repeated the assertion, however it is unknown where the fleet originated and would not have been under Edgar's command. Regardless, the fleet brought raw materials for constructing siege engines, but these were almost lost on the journey from the port to Antioch when part of the garrison sallied out. Bohemond and Raymond escorted the material, and after losing some of the materials and 100 people, they fell back to the crusader camp outside Antioch.[30] Before Bohemond and Raymond, rumours that they had been killed reached Godfrey who readied his men to rescue the survivors of the escort. However, his attention was diverted when another force sallied from the city to provide cover for the men returning from the ambush. Godfrey was able to hold off the attack until Bohemond and Raymond came to his aid.[31] The reorganised army then caught up with the garrison before it had reached the safety of Antioch's walls. The counter-attack was a success for the crusaders and resulted in the deaths of between 1,200 and 1,500 of Antioch's defenders.[30] The crusaders set to work building siege engines, as well as a fort, called La Mahomerie, to block the Bridge Gate and prevent Yaghi-Siyan attacking the crusader supply line from the ports of Saint Simon and Alexandretta, whilst also repairing the abandoned monastery to the west of the Gate of Saint George, which was still being used to deliver food to the city. Tancred garrisoned the monastery, referred to in the chronicles as Tancred's Fort, for 400 silver marks, whilst Count Raymond of Toulouse took control of La Mahomerie. Finally the crusader siege was able to have some effect on the well-defended city. Food conditions improved for the crusaders as spring approached and the city was sealed off from raiders.

Fatimid embassy

In April a Fatimid embassy from Egypt arrived at the crusader camp, hoping to establish a peace with the Christians, who were, after all, the enemy of their own enemies, the Seljuks. Peter the Hermit, was sent to negotiate. These negotiations came to nothing. The Fatimids, assuming the crusaders were simply mercenary representatives of the Byzantines, were prepared to let the crusaders keep Syria if they agreed not to attack Fatimid Palestine, a state of affairs perfectly acceptable between Egypt and Byzantium before the Turkish invasions. But the crusaders could not accept any settlement that did not give them Jerusalem. Nevertheless, the Fatimids were treated hospitably and were given many gifts, plundered from the Turks who had been defeated in March, and no definitive agreement was reached.

Capture of Antioch

The siege continued, and at the end of May 1098 a Muslim army from Mosul under the command of Kerbogha approached Antioch. This army was much larger than the previous attempts to relieve the siege. Kerbogha had joined with Ridwan and Duqaq and his army also included troops from Persia and from the Ortuqids of Mesopotamia. The crusaders were luckily granted time to prepare for their arrival, as Kerbogha had first made a three-week-long excursion to Edessa, which he was unable to recapture from Baldwin of Boulogne, who had taken it earlier in 1098.

The crusaders knew they would have to take the city before Kerbogha arrived if they had any chance of survival. Weeks earlier, Bohemond had secretly established contact with someone inside the city named Firouz, an Armenian guard who controlled the Tower of the Two Sisters.[32] Firouz's motivation was unclear even to Bohemond, perhaps avarice or revenge, but he offered to let Bohemond into the city in exchange for money and a title.[32] Bohemond then approached the other crusaders and offered access to the city, through Firouz, if they would agree to make Bohemond the Prince of Antioch.[32] Raymond was furious and argued that the city should be handed over to Alexios, as they had agreed when they left Constantinople in 1097, but Godfrey, Tancred, Robert, and the other leaders, faced with a desperate situation, gave in to Bohemond's demand.[32]

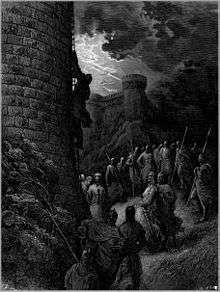

Despite this, on 2 June, Stephen of Blois and some of the other crusaders deserted the army. Later on the same day, Firouz instructed Bohemond to feign a march south over the mountains to ostensibly confront Kerbogha, but then to double-back at night and scale the walls at the Tower of the Two Sisters where Firouz held watch. This was done. Firouz allowed a small contingent of crusaders to scale the tower (including Bohemond), who then opened a nearby postern gate allowing a larger contingent of soldiers hiding in the nearby rocks to enter the city and overwhelm the alerted garrison.[32] The crusaders subsequently massacred thousands of Christian civilians along with Muslims, unable to tell them apart, including Firouz's own brother.[32] Yaghi-Siyan fled but was captured by Armenian and Syrian Christians some distance outside the city.[32] His severed head was brought to Bohemond.[32]

Second siege

By the end of the day on 3 June, the crusaders controlled most of the city, except for the citadel, which remained in hands of Yaghi-Siyan's son Shams ad-Daulah. John the Oxite was reinstated as patriarch by Adhemar of Le Puy, the papal legate, who wished to keep good relations with the Byzantines, especially as Bohemond was clearly planning to claim the city for himself. However, the city was now short on food, and Kerbogha's army was still on its way. Kerbogha arrived only two days later, on 5 June. He tried, and failed, to storm the city on 7 June, and by 9 June he had established his own siege around the city.[33]

More crusaders had deserted before Kerbogha arrived, and they joined Stephen of Blois in Tarsus. Stephen had seen Kerbogha's army encamped near Antioch and assumed all hope was lost; the deserters confirmed his fears. On the way back to Constantinople, Stephen and the other deserters met Alexios, who was on his way to assist the crusaders, and did not know they had taken the city and were now under siege themselves. Stephen convinced him that the rest of the crusaders were as good as dead, and Alexios heard from his reconnaissance that there was another Seljuk army nearby in Anatolia. He therefore decided to return to Constantinople rather than risking battle.[33]

Discovery of the Holy Lance

Meanwhile, in Antioch, on 10 June an otherwise insignificant priest from southern France[34] by the name of Peter Bartholomew came forward claiming to have had visions of St. Andrew, who told him that the Holy Lance was inside the city.[35] The starving crusaders were prone to visions and hallucinations, and another monk named Stephen of Valence reported visions of Christ and the Virgin Mary.[33] On 14 June a meteor was seen landing in the enemy camp, interpreted as a good omen.[35] Although Adhemar was suspicious, as he had seen a relic of the Holy Lance in Constantinople,[35] Raymond believed Peter. Raymond, Raymond of Aguilers, William, Bishop of Orange, and others began to dig in the cathedral of Saint Peter on 15 June, and when they came up empty, Peter went into the pit, reached down, and produced a spear point.[35] Raymond took this as a divine sign that they would survive and thus prepared for a final fight rather than surrender. Peter then reported another vision, in which St. Andrew instructed the crusader army to fast for five days (although they were already starving), after which they would be victorious.

Bohemond was skeptical of the Holy Lance as well, but there is no question that its discovery increased the morale of the crusaders. It is also possible that Peter was reporting what Bohemond wanted (rather than what St. Andrew wanted) as Bohemond knew, from spies in Kerbogha's camp, that the various factions frequently argued with each other. Kerbogha of Mosul was indeed suspected by most emirs to yearn for sovereignty in Syria and often considered as a bigger threat to their interests than the Christian invaders. On 27 June, Peter the Hermit was sent by Bohemond to negotiate with Kerbogha, but this proved futile and battle with the Turks was thus unavoidable. Bohemond drew up six divisions: he commanded one himself, and the other five were led by Hugh of Vermandois and Robert of Flanders, Godfrey, Robert of Normandy, Adhemar, and Tancred and Gaston IV of Béarn. Raymond, who had fallen ill, remained inside to guard the citadel with 200 men, now held by Ahmed Ibn Merwan an agent of Kerbogha.

Battle of Antioch

On Monday, 28 June, the crusaders emerged from the city gate,[33] with Raymond of Aguilers carrying the Holy Lance before them. Kerbogha hesitated against his generals' pleadings, hoping to attack them all at once rather than one division at a time, but he underestimated their size. He pretended to retreat to draw the crusaders to rougher terrain, while his archers continuously pelted the advancing crusaders with arrows. A detachment was dispatched to the crusader left wing, which was not protected by the river, but Bohemond quickly formed a seventh division and beat them back. The Turks were inflicting many casualties, including Adhemar's standard-bearer, and Kerbogha set fire to the grass between his position and the crusaders, but this did not deter them: they had visions of three saints riding along with them: St. George, St. Demetrius, and St. Maurice. The battle was brief and disastrous for the Turks. Duqaq deserted Kerbogha and this desertion reduced the great numerical advantage the Muslim army had over its Christian opponents. Soon the defeated Muslim troops were in panicked retreat.

Aftermath

As Kerbogha fled, the citadel under command of Ahmed ibn Merwan finally surrendered, but only to Bohemond personally, rather than to Raymond; this seems to have been arranged beforehand without Raymond's knowledge. As expected, Bohemond claimed the city as his own.[33] although Adhemar and Raymond disagreed. Hugh of Vermandois and Baldwin of Hainaut were sent to Constantinople, although Baldwin disappeared after an ambush on the way.[36] Alexios, however, was uninterested in sending an expedition to claim the city this late in the summer. Back in Antioch, Bohemond argued that Alexios had deserted the crusade and thus invalidated all of their oaths to him. Bohemond and Raymond occupied Yaghi-Siyan's palace, but Bohemond controlled most of the rest of the city and flew his standard from the citadel. It is a common assumption that the Franks of northern France, the Provencals of southern France, and the Normans of southern Italy considered themselves separate "nations" and that each wanted to increase its status. This may have had something to do with the disputes, but personal ambition is more likely the cause of the infighting.

Soon an epidemic broke out,[33] possibly of typhus, and on 1 August Adhemar of le Puy died.[37] In September the leaders of the crusade wrote to Pope Urban II, asking him to take personal control of Antioch,[35] but he declined. For the rest of 1098, they took control of the countryside surrounding Antioch, although there were now even fewer horses than before, and Muslim peasants refused to give them food. The minor knights and soldiers became restless and starvation began to set in and they threatened to continue to Jerusalem without their squabbling leaders. In November, Raymond finally gave in to Bohemond for the sake of continuing the crusade in peace and to calm his mutinous starving troops. At the beginning of 1099 the march was renewed, leaving Bohemond behind as the first Prince of Antioch, and in the spring the Siege of Jerusalem began under the leadership of Raymond.[38]

The success at Antioch was too much for Peter Bartholomew's skeptics. Peter's visions were far too convenient and too martial, and he was openly accused of lying. Challenged, Peter offered to undergo ordeal by fire to prove that he was divinely guided. Being in Biblical lands, they chose a Biblical ordeal: Peter would pass through a fiery furnace and would be protected by an angel of God. The crusaders constructed a path between walls of flame; Peter would walk down the path between the flames. He did so, and was horribly burned. He died after suffering in agony for twelve days on 20 April 1099.[39] There was no more said about the Holy Lance, although one faction continued to hold that Peter was genuine and that this was indeed the true Lance.

The Siege of Antioch quickly became legendary, and in the 12th century it was the subject of the chanson d'Antioche, a chanson de geste in the Crusade cycle. See also Artah.

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ Riley-Smith 1986, pp. 60–63

- ↑ Rogers 1997, pp. 26–28

- ↑ Kennedy 1994, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Previté-Orton 1975, p. 519

- 1 2 Runciman 1969, p. 309

- 1 2 Runciman 1951, pp. 214–215

- 1 2 3 Rogers 1997, pp. 25–26

- 1 2 Runciman 1969, p. 310

- 1 2 Rogers 1997, pp. 27, 29

- ↑ Rogers 1997, p. 25

- 1 2 Rogers 1997, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Quoted by Rogers 1997, p. 29

- ↑ Quoted by France 1996, p. 200

- 1 2 3 Rogers 1997, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Runciman 1969, pp. 310–311

- ↑ Rogers 1997, p. 32

- ↑ Asbridge 2000, pp. 26–27

- ↑ France 1996, p. 229

- ↑ Rogers 1997, p. 33

- 1 2 Rogers 1997, p. 33, citing Mayer 1972, p. 54

- ↑ Runciman 1951, p. 220

- 1 2 Runciman 1951, pp. 220–221

- 1 2 3 Runciman 1969, p. 312

- ↑ Rogers 1997, p. 34

- ↑ Runciman 1969, p. 313

- 1 2 Rogers 1997, p. 26

- ↑ Runciman 1969, pp. 313–314

- ↑ Runciman 1969, p. 314

- ↑ Runciman 1951, pp. 225–226

- 1 2 Rogers 1997, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Runciman 1951, p. 227

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Harari, Yuval Noah (2007). "The Gateway to the Middle East: Antioch, 1098". Special Operations in the Age of Chivalry, 1100–1550. The Boydell Press. pp. 53–73.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jonathan Simon Christopher Riley-Smith; Jonathan Riley-Smith (1 April 2003). The First Crusade and Idea of Crusading. Continuum. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-8264-6726-3.

- ↑ The Crusades: The Crescent and the Cross. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thomas F. Madden (19 September 2013). The Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 27–30. ISBN 978-1-4422-1576-4.

- ↑ By Gislebertus (of Mons), Laura Napran, Chronicle of Hainaut, 2005

- ↑ Riley-Smith 1986, p. 59

- ↑ Valentin, François (1867). Geschichte der Kreuzzüge. Regensburg.

- ↑ Nirmal Dass (2011). The Deeds of the Franks and Other Jerusalem-bound Pilgrims: The Earliest Chronicle of the First Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-4422-0497-3.

- Bibliography

- Asbridge, Thomas (2000), The Creation of the Principality of Antioch, 1098–1130, The Boydell Press, ISBN 978-0-85115-661-3

- France, John (1996), Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521589871

- Kennedy, Hugh (1994), Crusader Castles, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-42068-7

- Mayer, Hans E. (1972), John Gillingham (translator), ed., The Crusades, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198730156

- Previté-Orton, Charles William (1975) [1952], The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History Volume I (paperback ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-09976-5

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1986), The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, University of Pennsylvania, ISBN 9780485112917

- Roger, Randall (1997), Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780198206897

- Runciman, Steven (1951), The History of the Crusades Volume I: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Cambridge University Press

- Runciman, Steven (1969) [1955], "The First Crusade: Antioch to Ascalon", in Marshall W. Baldwin & Kenneth M. Setton, A History of the Crusades Volume One: The First Hundred Years (second ed.), The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 308–343

Further reading

- France, John (2001), "The Fall of Antioch during the First Crusade", in Michael Balard, Benjamin Z. Kedar, and Jonathan Riley-Smith, Dei Gesta per Francos: Études sur les croisades dédiées a Jean Richard, Ashgate, pp. 13–20

- Morris, Colin (1984), "Policy and vision: The case of the Holy Lance found at Antioch", in John Gillingham & J. C. Holt, War and Government in the Middle Ages: Essays in honour of J. O. Prestwich, The Boydell Press, pp. 33–45

- Peters, Edward, ed. (1971), The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials, University of Pennsylvania

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Siege of Antioch. |

- The Siege and Capture of Antioch: Collected Accounts

- The Gesta Francorum (see Chapters 10–15)

- The Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Jerusalem of Raymond of Aguilers (see Chapters 4–9)

- The Alexiad (see Chapter 11)

- Peter Tudebode's account at De Re Militari

Coordinates: 36°12′N 36°09′E / 36.200°N 36.150°E