Savva Morozov

_%3B_(eng.-Morozov_Savva_Timofeevich).jpg)

Savva Timofeyevich Morozov (Russian: Са́вва Тимофе́евич Моро́зов, 15 February [O.S. 3 February] 1862, Orekhovo-Zuevo, Bogorodsky Uyezd (Russian: Богородский уезд),[lower-alpha 1] Moskovskaya Guberniya (Russian: Московская губерния), Russian Empire – 26 May [O.S. 13 May] 1905, Cannes, France) was a Russian textiles magnate and philanthropist. Established by Savva Vasilievich Morozov (Russian: Савва Васильевич Морозов), the Morozov family was the fifth richest in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century.[2][3]

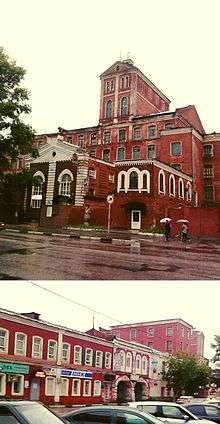

Morozov house at Trehsvyatitelskaya Lane 1-3c1

Morozov house at Trehsvyatitelskaya Lane 1-3c1 Morozov house from the garden

Morozov house from the garden- Another view of Morozov house

Savva Timofeyevich Morozov came from an Old Believer merchant family which held the hereditary civil rank of honorary citizen (Russian: Почётные граждане). This gave him freedom from conscription, freedom from corporal punishment, and freedom from taxation (Russian: Подушный оклад).[lower-alpha 2] He grew up at the Morozov house at Trehsvyatitelskaya Lane 1-3c1 (Russian: Большой Трёхсвятительский переулок) on Ivanovo Hill (Russian: Ивановская горка) in the White City (Russian: Белый город), now the boulevards, of Moscow.[4] He attended nearby gymnasium at Pokrovsky Gates.[4] His family home was the most expensive home in Moscow and its Morozov gardens (Russian: Морозовский сад) were a favorite place of S. Aksakov, F. Dostoevsky, A. Ostrovsky, L. Tolstoy, and P. Tchaikovsky.[5] Later, he studied physics and mathematics at Moscow University (1885) where he wrote a study on dye and met Mendeleev.[4] Beginning on January 7, 1885, at 10 o'clock in the morning, textile workers at the Morozov factories in Bogorodsk, especially Orekhovo-Zuyevo, went on strike for several weeks.[4] In 1885-1887, he studied chemistry at the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom). While he was in England, he studied the structure of the textile industry in Great Britain, especially Manchester.[4]

He married his second cousin's wife Zinaida Grigorievna née Zimin (Russian: Зинаида Григорьевна Зимина).[6][lower-alpha 3] They hosted lavish parties and balls that many distinguished Russians and Moscovites attended including Mammoth, Botkin, Feodor Chaliapin, Maxim Gorky, Anton Chekhov, Konstantin Stanislavski, Pyotr Boborykin, and others. On one of these balls recalled Olga Knipper, "I had to go to the ball at Morozova: I've never seen such luxury and wealth."[4]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Morozov was the largest shareholder of the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) under Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko.[7][8][9] During the summer of 1902, Savva funded Schechtel's, with participation of both Ivan Fomin and Alexander Galetsky, improvements of the Lianozov[lower-alpha 4] owned theatre built in 1890 at Kamergersky Lane 3 in Tverskoy.[7][8][9] The renovations incorporated Anna Golubkina's high relief plaster of The Wave above the right entrance of the theater.[10][11] In 1903, he funded the electrification of the theatre with its own electrical power station and added another small stage which is isolated from the main building to allow full rehearsals during performances on the main stage.[9] All of this made the MAT the most advanced theatre in Russia.[9] For the fifth and sixth seasons (1902-4), Morozov funded the entire cost of the equipment and the operating costs of the building, too.[9] This new theatre had seating for 1200 which was a third more than the older building and greatly enhanced its profitability. However, the rent increased for the seventh season (1904-5) and Morozov ceased paying for the leasehold and the operating cost. He would only pay back the principle for the cost of the improvements which took 9 years.[9] When Gorky's Summerfolk was not well received by Nemirovich-Danchenko and Stanislavski, Gorky left the theatre and Morozov followed.[8]

The Moscow Art Theatre, Kamergersky Lane 3, with exterior by Fyodor Schechtel

The Moscow Art Theatre, Kamergersky Lane 3, with exterior by Fyodor Schechtel Anna Golubkina's The Wave on Kamergersky Lane above the right entrance of the Moscow Art Theatre

Anna Golubkina's The Wave on Kamergersky Lane above the right entrance of the Moscow Art Theatre

Influenced by Maxim Gorky, he and his nephew Nikolai Pavlovich Schmit[lower-alpha 5] were significant financial contributors of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party including the newspaper Iskra.[12][13]

According to the author Suzanne Massie, in Land Of The Firebird, Morozov had approached his mother and family matriarch about introducing profit sharing with factory workers, one of the first industrialists to propose such an idea. His mother angrily removed Savva from the family business and one month later apparently despondent Morozov shot himself while in the south of France. Morozov died from a gunshot wound in Cannes, France. His death was officially ruled a suicide; however, various murder theories exist.[lower-alpha 6] His mansion became the headquarters of the Moscow Proletkult.[14]

Notes

- ↑ Established under the reign of Catherine the Great and existing before 1929, the old Bogorodsky Uyezd comprises Noginsk (Russian: Ногинск), Noginsky District (Russian: Ногинский район)), Elektrogorsk (Russian: Электрогорск), Pavlovo-Posadsky District (Russian: Павлово-Посадский район), Shchyolkovsky District (Russian: Щёлковский район); the eastern part of the cities of Balashikha (Russian: Балашиха), Zheleznodorozhny (Russian: Железнодорожный), Korolyov (Russian: Королёв), and Ivanteyevka (Russian: Ивантеевка); Orekhovo-Zuevo (Russian: Орехово-Зуево), and most of the Orekhovo-Zuyevsky District (Russian: Орехово-Зуевский район) and part of the Pushkinsky District (Russian: Пушкинский район) and part of the Ramensky District (Russian: Раменский район) which are in the northeastern part of today's Moscow region. Colloquially, Guslitsa (Russian: Гуслицы) is named after the Guslitsa River (Russian: Гуслица (река)) and refers to a location entirely within the Orekhovo-Zuyevsky District in which Old Believers lived. Its cultural heritage of home-crafts, mainly hand-written singing books, copper mouldings, and especially weaving, were instrumental in the rise of the Russian textile industry and the Morozov dynasty.[1]

- ↑ Before the introduction of income tax levies in the twentieth century, a poll tax was levied during censuses which were held to raise an Imperial Russian army.

- ↑ Zinaida's first husband was Sergei Vikulovicha Morozov (Russian: Сергея Викуловича Морозова) who was the third son of Savva's first cousin Vikulov Eliseevich Morozov (Russian: Викула Елисеевич Морозов).

- ↑ The Lianozovs were caviar and fish magnates with exclusive rights from the Persia to the fisheries of the southern Caspian Sea. Later, after the founding of Baku Oil in 1907, the Lianozov family were the 23rd richest family in Russia before the Great War.[2][3]

- ↑ Schmit was the son of Pavel Alexandrovich Schmit (Russian: Павел Александрович Шмит) and Savva's sister, Vera Vikulovna Morozova (Russian: Вере Викуловне Морозовой).

- ↑ Leonid Krasin is cited by Yuri Felshtinsky as the most likely assassin of Morozov.[7]

References

- ↑ Лизунов, Владимир С. (1992). Старообрядческая Палестина (из истории Орехово-Зуевского края) [Old Believers Palestine (from the history of Orekhovo-Zuevo region)] (in Russian). Орехово-Зуево (Orekhovo-Zuyevo): Богородское краеведение (Bogorodskoye District Studies). Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- 1 2 Гаков, Владимир (May 3, 2005). "Старые русские: Бакинские нефтяники, первый дилер Ford и Борис Абрамович — среди 30 богатейших людей и семей России 1900–1914 годов" [Old Russians: Baku oil, the first Ford dealer and Boris Abramovich - among the 30 richest individuals and families in Russia in 1900-1914]. Forbes (in Russian). Moscow. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- 1 2 "Миллионщики" [Millionaires]. Forbes (in Russian). Moscow. October 22, 2009. Archived from the original on March 16, 2011. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Лизунов, Владимир С. (1995). Минувшее проходит предо мною [The Past Is Held in Front of Me] (in Russian). Орехово-Зуево (Orekhovo-Zuyevo): Богородское краеведение (Bogorodskoye District Studies). Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Прощай, любимый город! (из Советский физик)" [Farewell, beloved city! (from Soviet Physicist)] (in Russian). Moscow: Moscow State University, M V Lomonosov (physics) department. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ↑ Whims of Fate accessed 17 may 2009

- 1 2 3 Felshtinsky, Yuri; Litvinenko, Alexander (October 26, 2010). Lenin and His Comrades: The Bolsheviks Take Over Russia 1917-1924. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 9781929631957.

- 1 2 3 Benedetti, Jean, ed. (1991). The Moscow Art Theatre Letters. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780878300846.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Орлов, Юрий (2005). "Экономика Московского Художественного театра 1898—1914 годов: к вопросу о самоокупаемости частных театров" [Economics of the Moscow Art Theatre's 1898-1914: the issue of self-financing private theaters]. Отечественные записки (in Russian). 4 (25). Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ↑ Голубкина, Анна Семёновна (1923). Несколько слов о ремесле скульптора [A few words about the sculptor's craft] (in Russian). Moscow: Издательство М. и С. Сабашниковых.

- ↑ Румянцев, Вячеслав (ed.). Голубкина Анна Семеновна (1864-1927): БИОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ УКАЗАТЕЛЬ [Golubkina Anna Semyonovna (1864-1927) BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX] (in Russian). Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ↑ Arto Luukkanen (1994), The Party of Unbelief, Helsinki: Studia Historica 48, ISBN 951-710-008-6, OCLC 832629341

- ↑ Vaksberg, Arkady (2007), The Murder of Maxim Gorky: A Secret Execution (in Russian), translated by Bludeau, Todd, New York: Enigma Books, ISBN 9781929631629

- ↑ Culture of the Future: The Proletkult Movement in Revolutionary Russia by Lynn Mally, University of California Press 1980