SLAP tear

| SLAP tear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Glenoid fossa of right side. (Glenoidal labrum labeled as "glenoid lig.") | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | orthopedics[*] |

| ICD-9-CM | 840.7 |

A SLAP tear or SLAP lesion is an injury to the glenoid labrum (fibrocartilaginous rim attached around the margin of the glenoid cavity). SLAP is an acronym for "superior labral tear from anterior to posterior".

Overview

The shoulder joint is a "ball-and-socket" joint.[1] However, the 'socket' (the glenoid fossa of the scapula) is small, covering at most only a third of the 'ball' (the head of the humerus). It is deepened by a circumferential rim of fibrocartilage, the glenoidal labrum. Previously there was debate as to whether the labrum was fibrocartilaginous as opposed to hyaline cartilage found in the remainder of the glenoid fossa. Previously, it was considered a redundant, evolutionary remnant, but is now considered integral to shoulder stability. Most agree that the proximal tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle becomes fibrocartilaginous prior to attaching to the superior aspect of the glenoid. The long head of the triceps brachii inserts inferiorly, similarly.[2] Together, all of those cartilaginous extensions are termed the 'glenoid labrum'.

A SLAP tear or lesion occurs when there is damage to the superior (uppermost) area of the labrum. These lesions have come into public awareness because of their frequency in athletes involved in overhead and throwing activities in turn relating to relatively recent description of labral injuries in throwing athletes,[3] and initial definitions of the 4 (major) SLAP sub-types,[4] all happening since the 1990s. The identification and treatment of these injuries continues to evolve.

Sub-types

Although ten varieties of SLAP lesion have been described on MRI or MR arthrography[5] seven clinical types are generally described.[6]

- Type I. Degenerative fraying of the superior portion of the labrum, with the labrum remaining firmly attached to the glenoid rim

- Type II. Separation of the superior portion of the glenoid labrum and tendon of the biceps brachii muscle from the glenoid rim

- Type III. Bucket-handle tears of the superior portion of the labrum without involvement of the biceps brachii (long head) attachment

- Type IV. Bucket-handle tears of the superior portion of the labrum extending into the biceps tendon

- Type V. Anteroinferior Bankart lesion that extends upward to include a separation of the biceps tendon

- Type VI. Unstable radial flap tears associated with separation of the biceps anchor

- Type VII. Anterior extension of the SLAP lesion beneath the middle glenohumeral ligament

Symptoms

Several symptoms are common but not specific:[7]

- Dull, throbbing, ache in the joint which can be brought on by very strenuous exertion or simple household chores.

- Difficulty sleeping due to shoulder discomfort. The SLAP lesion decreases the stability of the joint which, when combined with lying in bed, causes the shoulder to drop.

- For an athlete involved in a throwing sport such as baseball, pain and a catching feeling are prevalent. Throwing athletes may also complain of a loss of strength or significant decreased velocity in throwing.

- Any applied force overhead or pushing directly into the shoulder can result in impingement and catching sensations.

Treatment

There is evidence in literature to support both surgical and non-surgical forms of treatment.[8] In some, physical therapy can strengthen the supporting muscles in the shoulder joint to the point of reestablishing stability.

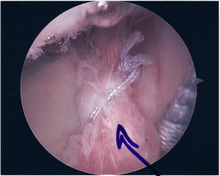

Surgical treatment of SLAP tears has become more common in recent years. The success rate for repairing isolated SLAP tears is reported between 74-94%.[8] While surgery can be performed as a traditional open procedure, an arthroscopic technique[9] is currently favored being less intrusive with low chance of iatrogenic infection.[10]

Associated findings within the shoulder joint are varied, may not be predictable and include:

- SLAP lesion – labrum/glenoid separation at the tendon of the biceps muscle

- Bankart lesion – labrum/glenoid separation at the inferior glenohumeral ligament

- Biceps Tendon - exclusion of pulley injury[11]

- Bone – glenoid, humerus — injury or degenerative change involving joint surface

- Anatomical variants — sublabral foramen, Buford Complex

It should be noted that while good outcomes with SLAP repair over the age of 40 are reported, both age greater than 40 and Workmen's Compensation status have been noted as independent predictors of surgical complications. This is particularly so if there is an associated rotator cuff injury. In such circumstances, it is suggested that labral debridement and biceps tenotomy is preferred.[12]

SLAP (Superior Labral Tear, Anterior to Posterior)

- Type 1

- Fraying of Superior Labrum

- Biceps Anchor Intact

- Type 2

- Superior Labrum detached

- Detachment of the Biceps Anchor

- Type 3

- Bucket Handle type tear of Superior Labrum

- Biceps Anchor INTACT

- Type 4

- Bucket Handle tear of Superior Labrum

- Extension of tear in Biceps Tendon

- Part of Biceps Anchor still INTACT

Procedure

Following inspection and determination of the extent of injury, the basic labrum repair is as follows.

- The glenoid and labrum are roughened to increase contact surface area and promote re-growth.

- Locations for the bone anchors are selected based on number and severity of tear. A severe tear involving both SLAP and Bankart lesions may require seven anchors. Simple tears may only require one.

- The glenoid is drilled for the anchor implantation.

- Anchors are inserted in the glenoid.

- The suture component of the implant is tied through the labrum and knotted such that the labrum is in tight contact with the glenoid surface.

Surgical rehabilitation

Surgical rehabilitation is vital, progressive and supervised. The first phase focusses on early motion and usually occupies post-surgical weeks one through three. Passive range of motion is restored in the shoulder, elbow, forearm, and wrist joints. However, while manual resistance exercises for scapular protraction, elbow extension, and pronation and supination are encouraged, elbow flexion resistance is avoided because of the biceps contraction that it generates and the need to protect the labral repair for at least six weeks. A sling may be worn, as needed, for comfort. Phase 2, occupying weeks 4 through 6, involves progression of strength and range of motion, attempting to achieve progressive abduction and external rotation in the shoulder joint. Phase 3, usually weeks 6 through 10, permits elbow flexion resistive exercises, now allowing the biceps to come into play on the assumption that the labrum will have healed sufficiently to avoid injury. Thereafter, isokinetic exercises may be commenced from weeks 10 through 12 to 16, for advanced strengthening leading to return to full activity based on post surgical evaluation, strength, and functional range of motion. The periods of isokinetics through final clearance are sometimes referred to as phases four and five.[13]

References

- ↑ Werner, C; Steinmann (July 1, 2005). "Treatment of Painful Pseudoparesis Due to Irreparable Rotator Cuff Dysfunction with the Delta III Reverse-Ball-and-Socket Total Shoulder Prosthesis". The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 87 (7): 1476. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02342. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ↑ Huber, WP; Putz, RV (December 1997). "Periarticular fiber system of the shoulder joint.". Arthroscopy. 13 (6): 680–91. doi:10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90001-3. PMID 9442320.

- ↑ Andrews, JR; Carson WG, Jr; McLeod, WD (Sep–Oct 1985). "Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps.". The American journal of sports medicine. 13 (5): 337–41. doi:10.1177/036354658501300508. PMID 4051091.

- ↑ Snyder, SJ; Karzel, RP; Del Pizzo, W; Ferkel, RD; Friedman, MJ (1990). "SLAP lesions of the shoulder.". Arthroscopy. 6 (4): 274–9. PMID 2264894.

- ↑ Mohana-Borges AV, Chung CB, Resnick D (December 2003). "Superior labral anteroposterior tear: classification and diagnosis on MRI and MR arthrography". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 181 (6): 1449–62. doi:10.2214/ajr.181.6.1811449. PMID 14627555.

- ↑ Aydin N, Sirin E, Arya A (Jul 18, 2014). "Superior labrum anterior to posterior lesions of the shoulder: Diagnosis and arthroscopic management". World J Orthop. 5 (3): 344–50. doi:10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.344. PMID 25035838.

- ↑ Chang D, Mohana-Borges A, Borso M, Chung CB (Oct 2008). "SLAP lesions: anatomy, clinical presentation, MR imaging diagnosis and characterization". Eur J Radiol. 68 (1): 72–87. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.02.026. PMID 18499376.

- 1 2 Patterson BM, Creighton RA, Spang JT, Roberson JR, Kamath GV (Jun 2, 2014). "Surgical Trends in the Treatment of Superior Labrum Anterior and Posterior Lesions of the Shoulder: Analysis of Data From the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Certification Examination Database". Am J Sports Med. 42 (8): 1904–10. doi:10.1177/0363546514534939. PMID 24890780.

- ↑ Huri G, Hyun YS, Garbis NG, McFarland EG (2014). "Treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a literature review". Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 48 (3): 290–7. doi:10.3944/AOTT.2014.3169. PMID 24901919.

- ↑ Babcock HM, Matava MJ, Fraser V (Jan 1, 2002). "Postarthroscopy surgical site infections: review of the literature". Clin Infect Dis. 34 (1): 65–71. doi:10.1086/324627. PMID 11731947.

- ↑ Patzer T, Kircher J, Lichtenberg S, Sauter M, Magosch P, Habermeyer P (May 2011). "Is there an association between SLAP lesions and biceps pulley lesions?". Arthroscopy. 27 (5): 611–8. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.01.005. PMID 21663718.

- ↑ Erickson J, Lavery K, Monica J, Gatt C, Dhawan A (Jun 24, 2014). "Surgical Treatment of Symptomatic Superior Labrum Anterior-Posterior Tears in Patients Older Than 40 Years: A Systematic Review". Am J Sports Med. doi:10.1177/0363546514536874. PMID 24961444.

- ↑ Ellenbecker TS, Sueyoshi T, Winters M, Zeman D (May 2008). "Descriptive report of shoulder range of motion and rotational strength six and 12 weeks following arthroscopic superior labral repair". N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 3 (2): 95–106. PMID 21509132.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SLAP lesion. |

- slaptear.com FAQs, Blogs, and discussion about slap tear injuries

- Radiographics search on Superior Labrum