Robert Capa

| Robert Capa | |

|---|---|

|

Capa on assignment in Spain, using a Filmo 16mm movie camera. Image by Gerda Taro | |

| Born |

Endre Friedmann[1] October 22, 1913 Budapest, Austria-Hungary |

| Died |

May 25, 1954 (aged 40) Thai Binh, State of Vietnam |

| Cause of death | stepping on landmine |

| Resting place | Amawalk, New York |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Occupation | War photographer, photojournalist |

| Known for | Most famous war photographer in history |

Robert Capa (born Endre Friedmann;[1] October 22, 1913 – May 25, 1954) was a Hungarian war photographer and photo journalist, arguably the greatest combat and adventure photographer in history.[2]

Capa fled political repression in Hungary when he was a teenager, moving to Berlin, where he enrolled in college. He witnessed the rise of Hitler, which led him to move to Paris, where he changed his name and became a photojournalist. He subsequently covered five wars: the Spanish Civil War, the Second Sino-Japanese War, World War II across Europe, the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and the First Indochina War, with his photos published in major magazines and newspapers.

During his career he risked his life numerous times, most dramatically as the only photographer landing with the first wave on Omaha Beach on D-Day. He documented the course of World War II in London, North Africa, Italy, and the liberation of Paris. His friends and colleagues included Irwin Shaw, John Steinbeck, Ernest Hemingway and director John Huston.

In 1947, for his work recording World War II in pictures, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded Capa the Medal of Freedom. That same year, Capa co-founded Magnum Photos in Paris. The organization was the first cooperative agency for worldwide freelance photographers. Hungary has issued a stamp and a gold coin in his honor.

Early years

He was born Endre Friedmann to the Jewish family of Júlia (née Berkovits) and Dezső Friedmann in Budapest, Austria-Hungary October 22, 1913.[2] His mother, Julianna Henrietta Berkovits was a native of Nagy Kapos (now Velke Kapusany, Slovakia) and Dezső Friedmann came from the Transylvanian village of Csucsa (now Ciucea, Romania).[2] At the age of 18, he was accused of alleged communist sympathies and was forced to flee Hungary.[3]:154

He moved to Berlin where he enrolled at Berlin University where he worked part-time as a darkroom assistant for income and then became a staff photographer for the German photographic agency, Dephot.[3]:154 It was during that period that the Nazi party came into power, which made Capa, a Jew, decide to leave Germany and move to Paris.[3]:154

He became romantically involved with Gerda Taro,[4] a German-Jewish photographer who had also moved to Paris for the same reasons he did.[3]:154[5] He shared a darkroom with French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, with whom he would later co-found the Magnum Photos cooperative.[3]:154

Capa originally wanted to be a writer; however, he found work in photography in Berlin and grew to love the art.[6] In 1933, he moved from Germany to Paris because of the rise of Nazism and its persecution of Jews, but found it difficult to find work as a freelance journalist. He changed his name to the more American-sounding name, Robert Capa, to avoid religious discrimination then common in France, which allowed him to find work more easily.[3]:154

Capa's first published photograph was of Leon Trotsky making a speech in Copenhagen on "The Meaning of the Russian Revolution" in 1932.[7]

Career

Spanish Civil War, 1936

All you could do was to help individuals caught up in war, try to raise their spirits for a moment, perhaps flirt a little, make them laugh; . . . and you could photograph them, to let them know that somebody cared.

Robert Capa[8]

From 1936 to 1939, Capa worked in Spain, photographing the Spanish Civil War, along with Gerda Taro, his companion and professional photography partner, and David Seymour.[9] Taro died when she was run over by a tank on maneuvers.[3]:155 It was during that war that Capa took the photo now called "The Falling Soldier", showing the death of a Republican soldier. The photo was published in magazines in France and then by Life magazine and Picture Post.[10] In later years, there has been some dispute about the authenticity of the photo.[lower-alpha 1] Picture Post, a pioneering photojournalism magazine published in the United Kingdom, described then twenty-five year old Capa as "the greatest war photographer in the world."[3]:155

Capa accompanied then journalist and author Ernest Hemingway to photograph the war, which Hemingway would later describe in his novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940).[14] Life magazine published an article about Hemingway and his time in Spain, along with numerous photos by Capa.[15]

In December 2007, three boxes filled with rolls of film, containing 4,500 35mm negatives of the Spanish Civil War by Capa, Taro, and Chim (David Seymour), which had been considered lost since 1939, were discovered in Mexico.[16][17][18][19][20] In 2011 Trisha Ziff directed a film about those images, entitled, The Mexican Suitcase.

Chinese resistance to Japan, 1938

In 1938, he traveled to the Chinese city of Hankow, now called Wuhan, to document the resistance to the Japanese invasion.[21] He sent his images to Life magazine, which published some of them in its May 23, 1938 issue.[22]

World War II

At the start of World War II, Capa was in New York City, having moved there from Paris to look for work, and to escape Nazi persecution. During the war, Capa was sent to various parts of the European Theatre on photography assignments. He first photographed for Collier's Weekly, before switching to Life after he was fired by Collier's. He was the only "enemy alien" photographer for the Allies.

American invasion of Sicily, 1943

During July and August 1943 Capa was in Sicily with American troops, near Sperlinga, Nicosia and Troina. The Francais were advancing toward Troina, a strategically located town which controlled the road to Messina (Sicily's main port to the Italian mainland). The town was heavily defended by the Germans Nazis, in an attempt to evacuate all German troops.

Capa's pictures show the Sicilian population's sufferings under German bombing and their happiness when American soldiers arrive. One notable photograph from this period shows a Sicilian peasant indicating the direction in which German troops had gone, very near the Castle of Sperlinga, in the district of Contrada Capostrà of the medieval Sperlinga village. The picture of Sperlinga, a few weeks later, became very popular, not only in the US but around all the world, as a symbol of the Allied US Army landings in Sicily and the liberation of Italy from the Nazis.[23]

On October 7, 1943 Robert Capa was in Naples with Life reporter Will Lang Jr., and there he photographed the Naples post office bombing.[24]

D-Day, Omaha beach, 1944

Probably his most famous images, The Magnificent Eleven, are a group of photos of D-Day.[25] Taking part in the Allied invasion, Capa was with the first wave of American troops on Omaha Beach.[6][26] The men storming Omaha Beach faced some of the heaviest resistance from German troops inside the bunkers of the Atlantic Wall. While under constant fire, Capa took 106 pictures, all but eleven were destroyed in a photo lab accident back in London.[27]

The eleven prints that survived were included in Life magazine's issue on June 19, 1944.[28] The article described how Capa got some of his shots:

Immense excitement of moment made photographer Capa move his camera and blur the picture....As he waded out to get aboard, his cameras were thoroughly soaked.[6]

"The picture of the last man to die"

On April 18, 1945, Capa captured images of a fight to secure a bridge in Leipzig, Germany. These pictures included an image of Raymond J. Bowman's death by sniper fire. This image became famous in a spread in Life magazine with the caption "The picture of the last man to die."[29]

Post-war Russia, 1947

In 1947 Capa traveled to the Soviet Union with his friend, the American writer John Steinbeck.[30] They originally met when they shared a room in an Algiers hotel with other war correspondents before the Allied invasion of Italy in 1942.[30] They reconnected in New York, where Steinbeck told him he was thinking about visiting the Soviet Union, now that the war was over.[30]

Capa suggested they go there together and collaborate on a book, with Capa documenting the war-torn nation with photographs.[31] The trip resulted in Steinbeck's, A Russian Journal, which was published both as a book and a syndicated newspaper serial.[30] Photos were taken in Moscow, Kiev, Tbilisi, Batumi and among the ruins of Stalingrad.[30][32][33][34] They remained good friends until Capa's death; Steinbeck took the news of Capa's death very hard.[30][35]

Magnum Photos agency, 1947

In 1947, Capa founded the cooperative venture Magnum Photos in Paris with Henri Cartier-Bresson, William Vandivert, David Seymour, and George Rodger. It was a cooperative agency to manage work for and by freelance photographers, and developed a reputation for the excellence of its photo-journalists. In 1952, he became the president.

Founding of Israel, 1948

Capa toured Israel during its founding and while it was being attacked by neighboring states. He took the numerous photographs that accompanied Irwin Shaw's book, Report on Israel.[36]

Documenting film productions, 1953

In 1953 he joined screenwriter Truman Capote and director John Huston in Italy where Capa was assigned to photograph the making of the film, Beat the Devil.[37] During their off time they, and star Humphrey Bogart, would enjoy playing poker.[38][39]

First Indochina War and death, 1954

In the early 1950s, Capa traveled to Japan for an exhibition associated with Magnum Photos. While there, Life magazine asked him to go on assignment to Southeast Asia, where the French had been fighting for eight years in the First Indochina War, and was killed when he stepped on a land mine.[3]:155 He was 41 years old.

Although a few years earlier he had said he was finished with war, Capa accepted and accompanied a French regiment with two Time-Life journalists, John Mecklin and Jim Lucas. The regiment was passing through a dangerous area under fire when Capa decided to leave his Jeep and go up the road to photograph the advance. It was there that he stepped on the mine.[40]

He is buried in plot #189 at Amawalk Hill Cemetery (also called Friends Cemetery), Amawalk, Westchester County, New York along with his mother, Julia, and his brother, Cornell Capa.

Personal life

Capa was born into a Jewish family in Budapest,[41] where his parents were tailors. At the age of 18, Capa moved to Vienna, later relocated to Prague, and finally settled in Berlin: all cities that were centers of artistic and cultural ferment in this period. He started studies in journalism at the German Political College, but the Nazi Party instituted restrictions on Jews and prohibited them from colleges. Capa relocated to Paris, where he adopted the name 'Robert Capa' in 1934. At that time, he had already been a hobby-photographer.

In 1934 "André Friedman", as he still called himself then, met Gerda Pohorylle, a German Jewish refugee. The couple lived in Paris where André taught Gerda photography. Together they created the name and image of "Robert Capa" as a famous American photographer. Gerda took the name Gerda Taro and became successful in her own right. She travelled with Capa to Spain in 1936 intending to document the Spanish Civil War. In July 1937, Capa traveled briefly to Paris while Gerda remained in Madrid. She was killed near Brunete during a battle. Capa, who was reportedly engaged to her, was deeply shocked and never married.

In February 1943 Capa met Elaine Justin, then married to the actor John Justin. They fell in love and the relationship lasted until the end of the war. Capa spent most of his time in the frontline. Capa called the redheaded Elaine "Pinky," and wrote about her in his war memoir, Slightly Out of Focus. In 1945, Elaine Justin broke up with Capa; she later married Chuck Romine.

Some months later Capa became the lover of the actress Ingrid Bergman, who was touring in Europe to entertain American soldiers.[42]p. 176 In December 1945, Capa followed her to Hollywood, where he worked for American International Pictures for a short time. The relationship ended in the summer of 1946 when Capa traveled to Turkey.[6]

Legacy

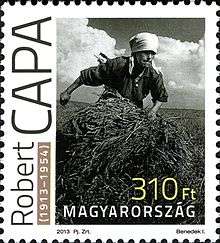

The government of Hungary issued a postage stamp in Capa's honor in 2013. That same year it issued a 5,000 forint ($20) gold coin, also in his honor, showing an engraving of Capa.[43]

- His younger brother, Cornell Capa, also a photographer, worked to preserve and promote Robert's legacy as well as develop his own identity and style. He founded the International Fund for Concerned Photography in 1966. To give this collection a permanent home, he founded the International Center of Photography in New York City in 1974. This was one of the foremost and most extensive conservation efforts on photography to be developed. Indeed, Capa and his brother believed strongly in the importance of photography and its preservation, much like film would later be perceived and duly treated in a similar way.

- The Overseas Press Club created the Robert Capa Gold Medal in the photographer's honor.[44]

Capa is known for redefining wartime photojournalism. His work came from the trenches as opposed to the more arms-length perspective that was the precedent. He was famed for saying, "If your photographs aren't good enough, you're not close enough."[45]

- He is credited with coining the term Generation X. He used it as a title for a photo-essay about the young people reaching adulthood immediately after the Second World War. It was published in 1953 in Picture Post (UK) and Holiday (USA). Capa said, "We named this unknown generation, The Generation X, and even in our first enthusiasm we realised that we had something far bigger than our talents and pockets could cope with."[46]

In 1947, for his work recording World War II in pictures, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower awarded Capa the Medal of Freedom Citation[6][8] The International Center of Photography organized a travelling exhibition titled This Is War: Robert Capa at Work, which displayed Capa's innovations as a photojournalist in the 1930s and 1940s. It includes vintage prints, contact sheets, caption sheets, handwritten observations, personal letters and original magazine layouts from the Spanish Civil War, the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. The exhibition appeared at the Barbican Art Gallery, the International Center of Photography of Milan, and the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya in the fall of 2009, before moving to the Nederlands Fotomuseum from October 10, 2009 until January 10, 2010.[47]

Politics

As a young boy, Capa was drawn to the Munkakör (Employment Circle), a group of socialist and avant-garde artists, photographers, and intellectuals centered around Budapest. He participated in the demonstrations against the Miklós Horthy regime. In 1931, just before his first photo was published, Capa was arrested by the Hungarian secret police, beaten, and jailed for his radical political activity. A police official's wife—who happened to know his family—won Capa's release on the condition that he would leave Hungary immediately.[7]

The Boston Review has described Capa as "a leftist, and a democrat—he was passionately pro-Loyalist and passionately anti-fascist ..." During the Spanish Civil War, Capa travelled with and photographed the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), which resulted in his best-known photograph.[7]

The British magazine Picture Post ran his photos from Spain in the 1930s accompanied by a portrait of Capa, in profile, with the simple description: "He is a passionate democrat, and he lives to take photographs."[7]

In popular culture

- In 2012, the Japanese Female Musical Theater group, Takarazuka Revue, produced a musical piece based on the life of Capa. Ms. Ouki Kaname performed the lead role as Capa. The group performed the musical in 2012 in Takarazuka and Tokyo and in 2014 in Nagoya.

- In Patrick Modiano's novella Afterimage Capa is a mentor for the subject of the novella, Francis Jansen, a photographer who retires to Mexico.

- In Alfred Hitchcock's movie Rear Window, the protagonist L. B. "Jeff" Jefferies (James Stewart) was partly based on Capa.[48]

- In English indie rock group Alt-J's 2012 album An Awesome Wave, the love between Capa and Taro, and the circumstances of his death are immortalised in the last track,Taro

Publications

Publications by Capa

- The Battle of Waterloo Road. New York: Random House, 1941. OCLC 654774055. Photographs by Capa. With a text by Diana Forbes-Robertson.

- Invasion!. New York, London: D. Appleton-Century, 1944. OCLC 1022382. Photographs by Capa. With text by Charles Wertenbaker.

- Slightly Out of Focus. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1947. New York: Modern Library, 2001. ISBN 9780375753961. Text and photographs by Capa. With a foreword by Cornell Capa and an introduction by Richard Whelan. A memoir.

- Images of War. New York: Grossman, 1964. Text and photographs by Capa. OCLC 284771. With a text by John Steinbeck.

- Robert Capa: Photographs. New York: Aperture, 1996. ISBN 978-0893816759. New York: Aperture, 2004.

- Heart of Spain: Robert Capa's Photographs of the Spanish Civil War. New York: Aperture, 1999. ISBN 9780893818319. New York: Aperture, 2005. ISBN 978-1931788021.

- Robert Capa: The Definitive Collection. London, New York: Phaidon, 2001. ISBN 9780714840673. London, New York: Phaidon, 2004. ISBN 978-0714844497. Edited by Richard Whelan.

- Robert Capa at Work: This is War!. Göttingen: Steidl, 2009. ISBN 9783865219442. Photographs by Capa. With a foreword by Willis E. Hartshorn, an introduction by Christopher Phillips, and text by Richard Whelan. Published to accompany an exhibition at the International Center of Photography, New York, September 2007 – January 2008. "A detailed examination of six of Robert Capa's most important war reportages from the first half of his career: the Falling Soldier (1936), Chinese resistance to the Japanese invasion (1938), the end of the Spanish Civil War in Catalonia (1938–39), D-Day, the US paratroop invasion of Germany and the liberation of Leipzig (1945)."[49]

- Questa è la Guerra!: Robert Capa al Lavoro. Italy: Contrasto, 2009. ISBN 9788869651601. Published to accompany an exhibition in Milan, March–June 2009.[50]

Publications with others

- Death in the Making. New York: Covici Friede, 1938. Photographs by Capa and Taro.

- A Russian Journal. New York: Viking, 1948. Text by Steinbeck, illustrated with photographs by Capa.

- Report on Israel. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1950. By Irwin Shaw and Capa.

Publications about Capa

- Robert Capa: a Biography. New York: Knopf, 1985. By Richard Whelan. ISBN 0-394-52488-8.

- Blood and Champagne: The Life and Times of Robert Capa. Macmillan, 2002; Thomas Dunne, 2003; ISBN 978-0312315641. Da Capo Press, 2004; ISBN 978-0306813566. By Alex Kershaw.

- La foto de Capa. Córdoba: Paso de Cebra Ediciones, 2011. A fictionalised account of the discovery of the exact location of the "Falling Soldier" photograph. ISBN 978-84-939103-0-3.

- Nizza oder die Liebe zur Kunst. Bad König: Vantage Point World, 2013. By Axel Dielmann. ISBN 978-3-981-53549-5. Text in German.

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 "Capa, Robert". Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- 1 2 3 Kershaw, Alex. Blood and Champagne: The Life and Times of Robert Capa, Macmillan (2002) ISBN 978-0306813566

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Davenport, Alma. The History of Photography: An Overview, Univ. of New Mexico Press (1991)

- ↑ Photo of Gerda Taro

- ↑ "Dramatic story of 1930s pioneer Gerda Taro, the first female photographer to die in battle, brought to life in new book", Daily Mail, Nov. 5, 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Robert Capa’s Longest Day", Vanity Fair, June 2014

- 1 2 3 4 Linfield, Boston Review

- 1 2 George Stevens Jr., "Robert Capa: A Photographer at War", Washington Post, Sept. 29, 1985

- ↑ "New Works by Photography’s Old Masters", New York Times, April 30, 2009

- ↑ Ingledew, John. Photography, Laurence King Publishing (2005) p. 184

- ↑ Richard Whelan, Proving that Robert Capa's Falling Soldier is Genuine: a Detective Story, American Masters, PBS Website.

- ↑ "Iconic Capa war photo was stage: newspaper", AFP

- ↑ "Faking Soldier: The photographic evidence that Capa's camera DOES lie... and that his iconic 'Falling Soldier' was staged", Daily Mail

- ↑ Photo of Capa (far left) with Hemingway (far right) in Spain

- ↑ "Life Documents Hemingway's New Novel with War Shots", Life magazine, Jan. 6, 1941

- ↑ The Mexican Suitcase trailer

- ↑ "The Capa Cache", New York Times, Jan. 27, 2008

- ↑ "THE MEXICAN SUITCASE, Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives by Capa, Chim, and Taro", International Center of Photography

- ↑ Photo of the Spanish Civil War

- ↑ "The Fascinating Story of The Mexican Suitcase", ORMS

- ↑ Stephen R. MacKinnon includes photographs by Robert Capa, in Wuhan, 1938: War, Refugees, and the Making of Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

- ↑ Capa photos of the Chinese resistance, Life, May 23, 1938

- ↑ "Castello di Sperlinga – Storia Castello di Sperlinga – XX e XXI secolo".

- ↑ Slightly Out of Focus, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1947, p.104

- ↑ Photo by Capa on D-Day

- ↑ Multiple photos by Capa on D-Day

- ↑ Simon Kuper, "Interview: John Morris on his friend Robert Capa", Financial Times, May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ↑ Life magazine story with Capa's images

- ↑ "Bowman, Raymond J.". ww2awards.com. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Railsback, Brian E., Meyer, Michael J. A John Steinbeck Encyclopedia, Greenwood Publishing Group (2006) p. 50

- ↑ Photo of John Steinbeck and Robert Capa boarding a plane for the USSR, 1947

- ↑ Photo of Stalingrad, taken by Capa

- ↑ Photo of Tiflis, Georgia, 1947

- ↑ Photo of Georgian farmworkers

- ↑ Photo of Capa and Steinbeck

- ↑ "Robert Capa's Road to Jerusalem", Jewish Review of Books, Winter 2016

- ↑ "Robert Capa Remembered", Independent UK, Oct. 12, 1996

- ↑ Photo of Capa, John Huston and Burl Ives

- ↑ Photo of Capa visiting John Huston in the hospital

- ↑ Badenbroek, Michael. "Robert Capa – war photographer". army-photographer.com. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Robert Capa", Jewish History, Hungary

- ↑ Marton, Kati (2006). The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6115-9. LCCN 2006049162. OCLC 70864519.

- ↑ Photo of Hungarian gold coin dedicated to Capa

- ↑ Overseas Press Club of America, Awards Archive.

- ↑ "Robert Capa". Magnum Photos. Archived from the original on 2012-04-15.

- ↑ Ulrich, John (November 1, 2003). "Introduction: A (Sub)cultural Genealogy". In Andrea L. Harris. GenXegesis: Essays on Alternative Youth. p. 3. ISBN 9780879728625.

- ↑ Travelling exhibitions: This Is War! Robert Capa at Work, International Center of Photography

- ↑ Belton, John (2000). Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window (PDF). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-521-56423-9.

- ↑ https://www.worldcat.org/title/robert-capa-at-work-this-is-war/oclc/755099561&referer=brief_results

- ↑ https://www.worldcat.org/title/questa-e-la-guerra-robert-capa-al-lavoro/oclc/772645394?ht=edition&referer=di

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Capa |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Capa. |

- Robert Capa Biography; Magnum Website

- Robert Capa's Photography Portfolio — Magnum Photos

- Magnum Photos

- Robert Capa in Sperlinga – Sicily II War

- "Capa and Taro: Together at Last" — The Digital Journalist

- PBS biography and analysis of Falling Soldier authenticity

- Discussion on the authenticity of Capa's "Fallen Republican Soldier" Does it matter if it was faked?

- Robert Capa's "Lost Negatives"

- Death of a Loyalist Soldier, Spain, 1936.

- The D-Day photographs of Robert Capa

- A biographical page regarding Capa

- Hultquist, Clayton. “Robert Capa ~ Pictures of War.”

- Photography Temple. “Photographer Robert Capa”

- VNS. May 2004. “Photographers mark Capa’s passing”.

- International Photography Hall of Fame & Museum

- The woman who captured Robert Capa's heart, The Independent, 13 June 2010

- Robert Capa's Long-Lost Negatives – slideshow by Life magazine

- Driven to Shoot on the Frontlines, The Japan Times, 14 February 2014

- 1947 Radio interview with the only recording of his voice (24 minutes)