Pyrrolizidine alkaloid

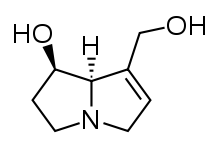

Pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs; sometimes referred to as necine bases) are a group of naturally occurring alkaloids based on the structure of pyrrolizidine. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are produced by plants as a defense mechanism against insect herbivores. More than 660 PAs and PA N-oxides have been identified in over 6,000 plants, and about half of them exhibit hepatotoxicity.[1] They are found frequently in plants in the Boraginaceae, Asteraceae, Orchidaceae and Fabaceae families; less frequently in the Convolvulaceae and Poaceae, and in at least one species in the Lamiaceae. It has been estimated that 3% of the world’s flowering plants contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids.[2] Honey can contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids,[3][4] as can grains, milk, offal and eggs.[5] To date (2011), there is no international regulation of PAs in food, unlike those for herbs and medicines.[6][7]

Unsaturated pyrrolizidine alkaloids are hepatotoxic, that is, damaging to the liver.[8][9] PAs also cause hepatic veno-occlusive disease and liver cancer.[10] PAs are tumorigenic.[11] Disease associated with consumption of PAs is known as pyrrolizidine alkaloidosis.

Of concern is the health risk associated with the use of medicinal herbs that contain PAs, notably borage leaf, comfrey and coltsfoot in the West, and some Chinese medicinal herbs.[11]

Some ruminant animals, for example cattle, showed no change in liver enzyme activities or any clinical signs of poisoning when fed plants containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids.[12] Yet Australian studies have demonstrated toxicity[13] Sheep, goats and cattle are much more resistant and tolerate much higher PA dosages, thought to be due to thorough detoxification via PA-destroying rumen microbes.[14] Males react more sensitively than females and fetuses and children.[15]

PA is also used as a defense mechanism for some organisms such as Utetheisa ornatrix. Utetheisa ornatrix caterpillars obtain these toxins from their food plants and use them as a deterrent for predators. PAs protect them from most of their natural enemies. The toxins stay in these organisms even when they metamorphose into adult moths, continuing to protect them throughout their adult stage.[16]

Ecology

Many plants contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids, and in turn there are many insects which consume the plants and build up the alkaloids in their bodies.[17] For example, male Queens utilize pyrrolizidine alkaloids to produce pheromones useful for mating.[18]

Plants species containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids

- Adenostyles alliariae

- Adenostyles glabra

- Ageratum conyzoides

- Ageratum houstonianum[19]

- Anchusa officinalis[20]

- Arnebia euchroma

- Borago officinalis (< 10 ppm, non-toxic)

- Cacalia hastata

- Cacalia hupehensis

- Chromolaena odorata

- Cordia myxa

- Crassocephalum crepidioides

- Crotalaria albida

- Crotalaria assamica

- Crotalaria crispat

- Crotalaria dura

- Crotalaria globifera

- Crotalaria mucronata

- Crotalaria sesseliflora

- Crotalaria spectabilis

- Crotalaria tetragona

- Crotalaria retusa

- Cynoglossum amabile

- Cynoglossum lanceolatum

- Cynoglossum officinale

- Cynoglossum zeylanicum

- Echium plantagineum[21]

- Echium vulgare

- Emilia sonchifolia

- Eupatorium cannabinum

- Eupatorium chinense

- Eupatorium fortunei

- Eupatorium japonicum

- Eupatorium purpureum[22]

- Farfugium japonicum

- Gynura bicolor

- Gynura divaricata

- Gynura segetum

- Heliotropium amplexicaule[21]

- Heliotropium europaeum[21]

- Heliotropium indicum

- Lappula intermedia

- Ligularia cymbulifera

- Ligularia dentata

- Ligularia duiformis

- Ligularia heterophylla

- Ligularia hodgsonii

- Ligularia intermedia

- Ligularia lapathifolia

- Ligularia lidjiangensis

- Ligularia platyglossa

- Ligularia tongolensis

- Ligularia tsanchanensis

- Ligularia vellerea

- Liparis nervosa

- Lithospermum erythrorhizon

- Neurolaena lobata

- Petasites japonicus

- Senecio alpinus

- Senecio argunensis

- Senecio brasiliensis[23]

- Senecio chrysanthemoides

- Senecio cineraria

- Senecio glabellus

- Senecio integrifolius var. fauriri

- Senecio interggerrimus

- Senecio jacobaea[21]

- Senecio lautus[21]

- Senecio linearifolius[21]

- Senecio madagascariensis[21]

- Senecio nemorensis

- Senecio quadridentatus[21]

- Senecio riddelli

- Senecio scandens

- Senecio vulgaris

- Syneilesis aconitifolia

- Symphytum officinale[24]

- Tussilago farfara[11]

Monocrotaline is the main PA found in Crotalaria species.[25]

The effect of PAs in humans, that is PAILDs,[26] of epidemic proportions was recorded after a long field-level epidemiological investigation in the northern region of Ethiopia- Tigray.

References

- ↑ Radominska-Pandya, A (2010). "Invited Speakers". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 42 (S1): 1–2. doi:10.3109/03602532.2010.506057. PMID 20842800.

- ↑ Smith, L. W.; Culvenor, C. C. J. Plant sources of hepatotoxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids. J. Nat. Prod. 1981, 44, 129-15

- ↑ Kempf M, Reinhard A, Beuerle T.,Pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) in honey and pollen-legal regulation of PA levels in food and animal feed required. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010 Jan;54(1):158-68.

- ↑ Edgar, John A., Erhard Roeder, and Russell J. Molyneux, J. Agric. Food Chem., Vol. 50, No. 10, 2002, "Honey from Plants Containing Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids: A Potential Threat to Health"

- ↑ PYRROLIZIDINE ALKALOIDS IN FOOD http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/_srcfiles/tr2.pdf

- ↑ Coulombe, Roger A., Jr., "Pyrrolizidine alkaloids in foods" Advances in Food and Nutrition Research Volume 45, 2003, Pages 61-99

- ↑ German Commission E monographs

- ↑ "Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook: Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids". Bad Bug Book. United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ Schoental, R.; Kelly, JS (April 1959). "Liver lesions in young rats suckled by mothers treated with the pyrrolizidine (Senecio) alkaloids, lasiocarpine and retrorsine.". The Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. 2 (77): 485–495. doi:10.1002/path.1700770220. PMID 13642195.

- ↑ Schoental, R., "Toxicology and Carcinogenic Action of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids", Cancer Research No.28, pp.2237-2246, November 1968

- 1 2 3 Fu, P.P., Yang, Y.C., Xia, Q., Chou, M.C., Cui, Y.Y., Lin G., "Pyrrolizidine alkaloids-tumorigenic components in Chinese herbal medicines and dietary supplements", Journal of Food and Drug Analysis, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2002, pp. 198-211

- ↑ Skaanild, M.T.; Friis, C.; Brimer, L. (2001). "Interplant alkaloid variation and Senecio vernalis toxicity in cattle". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 43 (3): 147–151.

- ↑ Noble, J.W.; Crossley, J.; Hill, B.D.; Pierce, R.J.; McKenzie, R.A.; Debritz, M.; Morley, A.A. (1994). "Pyrrolizidine alkaloidosis of cattle associated with Senecio lautus". Australian Veterinary Journal. 71 (7): 196–200. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1994.tb03400.x.

- ↑ Wiedenfeld H., Edgar J., "Toxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids to humans and ruminants" Phytochemistry Reviews (1-15) 2010

- ↑ Wiedenfeld, H.; Edgar, J. "Toxicity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids to humans and ruminants". Phytochemistry Reviews. 2010: 1–15.

- ↑ Conner, W.E. (2009). Tiger Moths and Woolly Bears—behaviour, ecology, and evolution of the Arctiidae. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1-10.

- ↑ Male sex pheromone of a giant danaine butterfly,Idea leuconoe

- ↑ Scott, James A. (1997). The Butterflies of North America. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 228–232.

- ↑ Wiedenfeld, H; Andrade-Cetto, A (2001). "Pyrrolizidine alkaloids from Ageratum houstonianum Mill.". Phytochemistry. 57 (8): 1269–71. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00192-3. PMID 11454357.

- ↑ Broch-Due, Å. I. and Aasen, A. J. Alkaloids of Anchusa officinalis L. Identification of the Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid Lycopsamine. Acta Chem. Scand. B 34 (1980) 75 - 77

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The MERCK Veterinary Manual, Table 5

- ↑ Wood, Matthew. "The Book of Herbal Wisdom: Using Plants As Medicines." Berkeley CA. North Atlantic Books. 1997.

- ↑ Rizk A. M. Naturally Occurring Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. 1990.

- ↑ Yeong M. L.; et al. (1990). "Hepatic veno-occlusive disease associated with comfrey ingestion". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 5 (2): 211–214. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.1990.tb01827.x. PMID 2103401.

- ↑ "Pharmacologic Study of some plant species from the Brazilian Northeast. Vasconcellos S. M. et al., cited in "Medicinal Plants" Varela A Ibanez J (Eds), Nova Pub. 2009.

- ↑ "Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid Induced Liver Diseases", cited in "Evaluation of the Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid Induced Liver Disease (PAILD) Active Surveillance System in Tigray, Ethiopia". Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 5 (1). PMC 3692817

.

.

23. http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/stories/Ethiopia.html, Investigating Liver disease in Ethiopia

External links

- Subhuti Dharmananda. "Safety issues affecting herbs: pyrrolizidine alkaloids". Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon.

- E. Röder (1995). "Medicinal plants in Europe containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids". Die Pharmazie. Henriette's herbal (Henriette Kress). 50: 83–98.

- Pyrrolizidine alkaloids at KEGG