Piprahwa

| Piprahawa Piprahava | |

|---|---|

| village | |

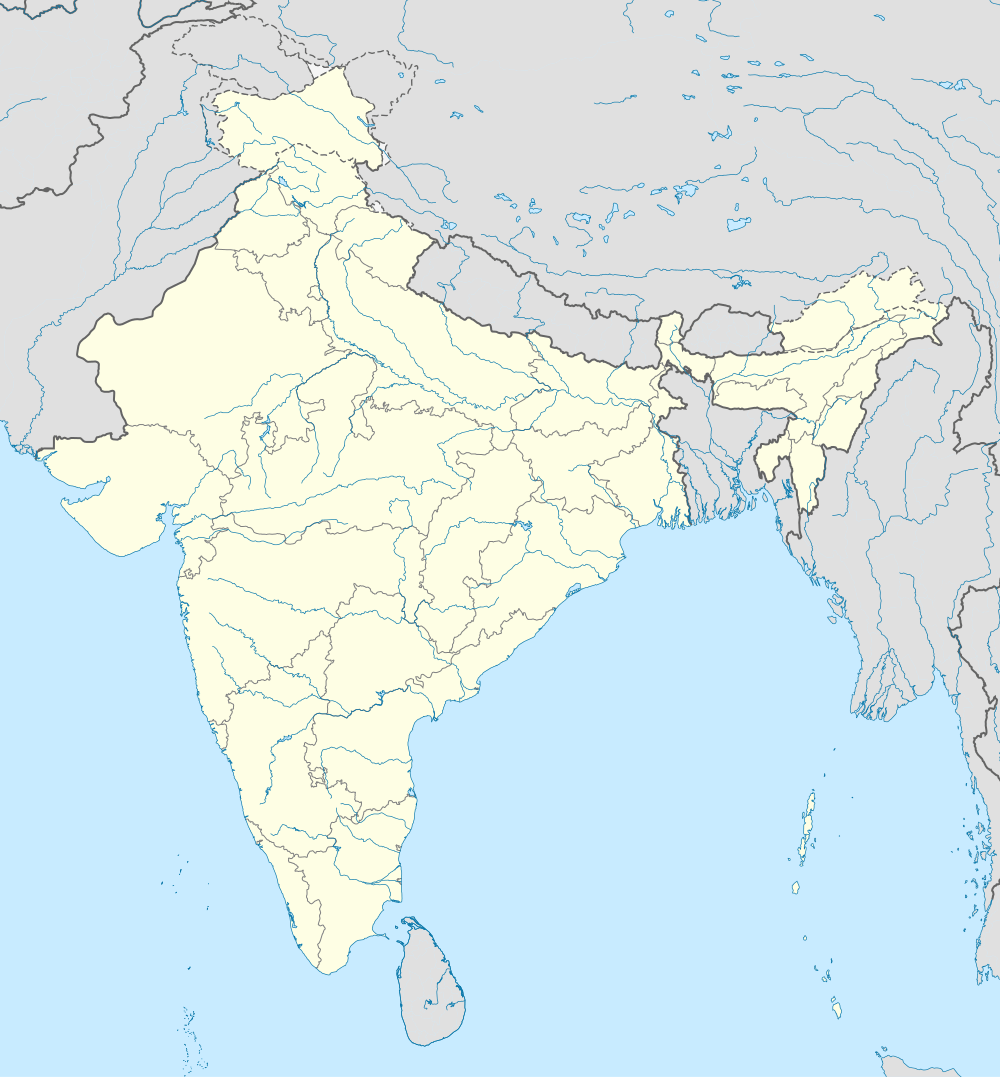

Piprahawa  Piprahawa Location in Uttar Pradesh, India | |

| Coordinates: 27°26′35″N 83°07′40″E / 27.443000°N 83.127800°ECoordinates: 27°26′35″N 83°07′40″E / 27.443000°N 83.127800°E | |

| Country |

|

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| District | Siddharthnagar |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Hindi |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+05:30) |

| Pilgrimage to |

| Buddha's Holy Sites |

|---|

|

| The Four Main Sites |

| Four Additional Sites |

| Other Sites |

| Later Sites |

Piprahwa is a village near Birdpur in Siddharthnagar district of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Kalanamak, a scented and spicy variety of rice is grown in this area.[1]

Piprahwa is best known for its archaeological site. A large stupa and the ruins of several monasteries are located within the site. Ancient residential complexes and shrines were uncovered at the adjacent mound of Ganwaria. Some scholars have suggested that modern-day Piprahwa-Ganwaria was the site of the ancient city of Kapilavastu, the capital of the Shakya kingdom, where Siddhartha Gautama spent the first 29 years of his life.[2][3][4] Others suggest that the original site of Kapilavastu is located 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) to the northwest, at Tilaurakot, in what is currently Kapilvastu District in Nepal.[2][5][6][note 1]

Excavation by William Claxton Peppe

A buried stupa was discovered by William Claxton Peppe, a British colonial engineer and landowner of an estate at Piprahwa in January 1898. Peppe led a team in excavating a large earthen mound on his land. Having cleared away scrub and jungle, they set to work building a deep trench through the mound. Eventually they came to a large stone coffer which contained five small vases containing bone fragments, ashes and jewels.[2] On one of the vases was a Brahmi inscription which was translated by Bühler to mean "This relic-shrine of divine Buddha (is the donation) of the Sakya-Sukiti brothers, associated with their sisters, sons, and wives",[3] implying that the bone fragments were part of the remains of Gautama Buddha.[8] In the following decade or so epigraphists debated the precise meaning of the inscription. One scholar, John Fleet, challenged the opinion of such fellow academics as M. Senart and M. Barth and proposed that it referred to the Buddha’s kinsman rather than the Buddha himself.[9][10] However, Harry Falk agrees with the original interpretation as translated by Georg Buhler and Vincent Smith that the depositors believed these to be the remains of the Buddha himself. Falk translates the inscription as "these are the relics of the Buddha, the Lord" and concludes that the reliquary found at Piprahwa did contain a portion of the ashes of the Buddha and that the inscription is authentic.[11]

Noting the challenges that isolated finds present to paleographical study, epigraphist and archaeologist Ahmad Hasan Dani observed in 1997 that "The Piprahwa vase, found in the Basti District, U.P., has an inscription scratched on the steatite stone in a careless manner. The style of writing is very poor, and there is nothing in it that speaks of the hand of the Asokan scribes". He concludes that "the inscription may be confidently dated to the earlier half of the second century B.C."[12]

Distribution of the relics

At the urging of Jinavaravansa, a Siamese Monk who arrived at Piprahwa soon after the discovery, the bone relics from Peppe´s excavation were offered by the government of India to the King of Siam, who shared them with buddhist communities in other countries.[13][14] They are now distributed across several locations, including:

- the Golden Mount Temple in Bangkok, Thailand[14]

- the Dipaduttamrama Temple (also known as the Jewel Stupa) in Colombo, Sri Lanka

- the Ruwanwelisaya stupa in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka

- the government of India allowed W C Peppe to keep a number of duplicates from the excavation,[15] this portion of the discovery has remained with the Peppe family

Today, the relics from the original and the 1970s excavations of the Piprahwa stupa are revered by many Buddhists the world over. In 1978 the Indian government allowed their share of the discovery to be exhibited in Sri Lanka and more than 10 million people paid homage. They were also exhibited in Mongolia in 1993, Singapore in 1994, South Korea in 1995 and Thailand in 1996 and again in Sri Lanka in 2012.

Excavations by the Archaeological Survey of India

From 1971-1973, a team of the Archaeological Survey of India led by K.M. Srivastava resumed excavations at the Piprahwa stupa site. The team discovered a casket containing fragments of charred bone, at a location several feet deeper than the coffer that W.C. Peppe had previously excavated. As the relic containers were found in the deposits from the period of Northern Black Polished Ware, Srivastava dated the find to the fifth-fourth centuries BCE, which would be consistent with the period in which the Buddha is believed to have lived.[4]

The bone fragments recovered by Srivastava's team are currently located at the National Museum, New Delhi.[16] More than ten million people reportedly paid homage to the relics when they were first exhibited in Sri Lanka in 1978, and in August 2012 the Indian government once more allowed the relics to be exhibited in Sri Lanka.

The main stupa at Piprahwa, one of the earliest so far discovered in India, was built in three phases. In the 6th-5th century BCE it was raised by piling up natural earth from the surrounding area. In the centre there was a chamber of burnt-bricks to keep sacred relics. Phase II (3rd century BCE) is consisting of filling thick clay over the structure and of having two tiers to reach a height of 4.55m. In phase III, during the Kushan period, the stupa was extensively enlarged and reached a height of 6.35m.[17] The largest structure after the stupa is the Eastern Monastery that is measuring 45.11mx41.14m with a courtyard and more than thirty cells around it. There is also the Southern Monastery and the Western Monastery and the smaller Northern Monastery at Piprahwa.[17]

Today the ancient sites of Piprahwa and Ganwaria are hosting the Kapilavastu Museum that is controlled by the Archaeological Survey of India.[17]

Location of ancient Kapilavastu

Some scholars have suggested that modern-day Piprahwa was the site of the ancient city of Kapilavastu, the capital of the Shakya kingdom, where Siddhartha Gautama spent the first 29 years of his life.[2][3][4][18] Others suggest that the original site of Kapilavastu is located 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) to the northwest, at Tilaurakot, in what is currently Kapilvastu District in Nepal.[7][5][6] This question is especially important to scholars of Buddhist history, as Kapilavastu was the capital of the Shakya kingdom. King Śuddhodana and Queen Māyādevī lived at Kapilavastu, as did their son Prince Siddhartha Gautama until he left the palace at 29 years of age.

Notes

- ↑ According to Allen, "The best hypothesis we are ever likely to arrive on the basis of what we know at present at is that the Kapilavastu in which the Prince Siddhartha grew to manhood was a settlement enclosed within a walled palisade beside the modern River Banganga, pretty much where the ruins of Tilaurakot are today."[7]

References

- ↑ Mishra 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 Peppe 1898, pp. 573–88.

- 1 2 3 Bühler 1898, p. 388.

- 1 2 3 Srivastava 1980, pp. 103–10.

- 1 2 Tuladhar 2002, pp. 1-7.

- 1 2 Sharda 2015.

- 1 2 Allen 2008, p. 262.

- ↑ Peppe 1898, pp. 584–85.

- ↑ Fleet 1907, pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Museums of India.

- ↑ Secrets of the Dead.

- ↑ Dani 1997.

- ↑ Smith 1898, p. 868.

- ↑ Allen 2008, p. 207.

- ↑ Srivathsan 2012.

- 1 2 3 Archaeological Survey of India 2015.

- ↑ Srivastava 1979, pp. 61-74.

Sources

- Allen, Charles (2008). The Buddha and Dr Führer: an archaeological scandal (1st ed.). London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905791-93-4.

- Archaeological Survey of India (2015), Kapilavastu Museum

- Allen, Charles (2012), "What happened at Piprahwa: A chronology of events relating to the excavation in January 1898 of the Piprahwa Stupa in Basti District, North-Western Provinces and Oude (Uttar Pradesh), India, and the associated 'Piprahwa Inscription', based on newly available correspondence", Zeitschrift für Indologie und Südasienstudien, 29: 1–19OCLC 64218646

- Bühler, Georg (April 1898), "Preliminary note on a recently discovered Sakya inscription", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Correspondence: Note 14): 387–389, JSTOR 25207982 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Dani, AH (1997), Indian Palaeography (3rd ed.), New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, p. 56, ISBN 978-8121500289

- Fleet, J. F. (1907), "The Inscription on the Piprahwa Vase", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 105–130, JSTOR 25210369 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Jinavaravansa, P. C.; Jumsai, Sumet (2003), The Ratna Chetiya Dipaduttamarama, Colombo, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka, New Series 48, 213-236 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Mishra, S (2005-09-15), "Kalanamak: the future of Indian scented rice?", Down To Earth magazine, New Delhi: Society for Environmental Communications, retrieved 2014-11-29

- Museums of India, National Portal and Digital Repository. Inscribed Relic Casket from Piprahwa, Indian Museum, Kolkata

- Peppe, WC (July 1898), "The Piprahwa Stupa, containing relics of Buddha", With a note by V.A. Smith. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Article XXIII): 573–88, JSTOR 25208010 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Secrets of the Dead: Bones of the Buddha - Transcript, PBS, retrieved April 16, 2015

- Sharda, Shailvee (May 4, 2015), "UP's Piprahwa is Buddha's Kapilvastu?", Times of India

- Smith, V. A. (Oct., 1898), The Piprāhwā Stūpa, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, p. 868 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Srivastava, KM (1979), "Kapilavastu and Its Precise Location", East and West, 29 (1/4): 61–74, JSTOR 29756506 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Srivastava, KM (1980), "Archaeological Excavations at Piprāhwā and Ganwaria and the Identification of Kapilavastu", The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 13 (1): 103–10

- Srivathsan, A (2012-08-20), "Gautama Buddha, four bones and three countries", Colombo Telegraph, Colombo, Sri Lanka, retrieved 2014-11-29

- Tuladhar, Swoyambhu D. (November 2002), "The Ancient City of Kapilvastu - Revisited" (PDF), Ancient Nepal (151): 1–7

External links

- Bones of the Buddha

- The Piprahwa Project

- Kapilavastu Museum

- The Piprahwa Jewels

- The Piprahwa Deceptions: Setups and Showdown by Terry Phelps (2008)