Pharyngeal jaw

Pharyngeal jaws are a "second set" of jaws contained within an animal's throat, or pharynx, distinct from the primary or oral jaws. They are believed to have originated as modified gill arches, in much the same way as oral jaws.

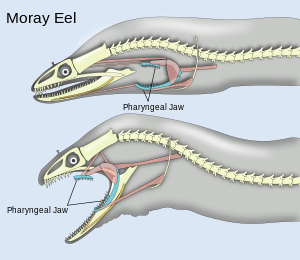

Although approximately 30,000 species of fishes are known to have pharyngeal jaws, in many species having their own teeth, the most notable example of animals possessing them is the moray eels of the family Muraenidae. Unlike those in other fishes known to have them, those of the moray are highly mobile. This is possibly a response to their inability to swallow as other fishes do by creating a negative pressure in the mouth, perhaps induced by their restricted environmental niche (burrows). Instead, when the moray bites prey, it first bites normally with its oral jaws, capturing the prey. Immediately thereafter, the pharyngeal jaws are brought forward and bite down on the prey to grip it; they then retract, pulling the prey down the moray eel's gullet, allowing it to be swallowed.[1]

Another notable example of animals possessing pharyngeal jaws are the fish from the family Cichlidae. Cichlid pharyngeal jaws have become very specialized in prey processing and may have helped cichlid fishes become one of the most diverse families of vertebrates.[2] However, later studies based on Lake Victoria cichlids suggest that this trait may also become a handicap when competing with other predator species.[3]

Popular culture

The very mobile pharyngeal jaws of moray eels were discovered in 2007 by UC Davis scientists. Almost three decades before (1979), the fiction xenomorph creature from Alien series was first depicted showing a second set of jaws for attacking its prey. At that time, pharyngeal jaws in other fishes were already known, however.[4]

References

- ↑ Mehta, Rita S.; Wainwright, Peter C. (2007-09-06). "Raptorial jaws in the throat help moray eels swallow large prey". Nature. 449 (7158): 79–82. doi:10.1038/nature06062. PMID 17805293. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- ↑ Hulsey, C. D., F. J. Garcia de Leon, and R. Rodiles-Hernandez. 2006. Micro- and macroevolutionary decoupling of cichlid jaws: A test of Liem’s key innovation hypothesis. Evolution. 60:2096-2109.

- ↑ McGee, Matthew D.; Borstein, Samuel R.; Neches, Russell Y.; Buescher, Heinz H.; Seehausen, Ole; Wainwright, Peter C. (2015-11-27). "A pharyngeal jaw evolutionary innovation facilitated extinction in Lake Victoria cichlids". Science. 350 (6264): 1077–1079. doi:10.1126/science.aab0800. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26612951.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (2007-09-11). "If the First Bite Doesn't Do It, the Second One Will". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-07-03.

External links

- National Science Foundation article explaining moray eel pharyngeal jaws

- Video of a moray eel eating