Performance practice of Bach's music

Johann Sebastian Bach's music has been performed by musicians of his own time (including himself), and in the second half of the eighteenth century by his sons and students, and by the next generations of musicians and composers such as the young Beethoven. Felix Mendelssohn renewed the attention for Bach's music by his performances in the 19th century. In the 20th century Bach's music was performed and recorded by artists specializing in the music of the composer, such as Albert Schweitzer, Helmut Walcha and Karl Richter. With the advent of the historically informed performance practice Bach's music was prominently featured by artists such as Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Gustav Leonhardt and Sigiswald Kuijken.

In Bach's time

In Bach's time his music was experienced as exceptionally demanding for singers and instrumentalists, while he expected the same virtuosity of them as he could accomplish on organ and other keyboard instruments. That level of virtuosity was deemed "impossible", especially as he detailed how and with which ornamentation the music was to be executed.[1]

Keyboard

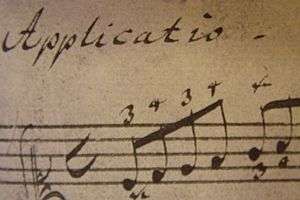

For his keyboard-playing Bach is largely considered an autodidact. In 1716 François Couperin's L'art de toucher le clavecin had appeared. Bach knew Couperin's harpsichord music: one of his pieces ended up in the Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach.[2] The Applicatio in C major BWV 994, the first piece in the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, is one of a very few instances where Bach indicates fingering.[3] Apart from such minute indications there are no direct descriptions by the composer of how he taught his students to play the keyboard. Generally, however, it is assumed that the indications in L'art de toucher le clavecin are not too far from how Bach played the harpsichord.

Organ

The earliest printed report about Johann Sebastian Bach qualifies him as a "famous organist".[4] In 1737 Johann Adolf Scheibe gives a description of his organ-playing: "[Bach] is as astonishly accomplished. It is hard to understand how wonderful and agile he can manage his fingers and feet to come together and move apart again, making the widest jumps, without a single false note, and without, with such a violent movement, moving his body around."[1]

Continuo

A document written in 1738 documents Bach's ideas about performance of the figured bass.[5]

Choir and orchestra

From documents written by Bach in his Leipzig period it can be seen that the expected at least three (but preferably four) singers per voice group in a SATB choir. There were no separate vocal soloists: vocal solo parts were performed by choristers. An orchestra for performing his church music would consist of two to three first violins, and as many second violins, two times two viola players, two cellists, a violone, two to three oboists, one or two bassoons, three trumpets and timpani.[6]

The composition of his orchestra varied widely depending on piece, for instance for the Passions there were no trumpets or timpani (while these festive instruments were deemed unsuitable for the time of Lent). Many of his pieces require flutes (traverso and/or recorder), and sometimes more exceptional instruments such as the lituus.

Four-part chorales and motets were mostly performed with a colla parte instrumentation and/or continuo.

Galant period

The first decades after the composer's death his music lived on mostly in keyboard music used for teaching by his students. By the time his son Carl Philipp Emanuel wrote his keyboard method the piano was replacing the harpsichord as standard keyboard instrument. Johann Christoph Altnickol, Johann Kirnberger, Johann Friedrich Agricola and Johann Peter Kellner performed Bach's music and taught it to the next generations.

Carl Philipp Emanuel and his older brother Wilhelm Friedemann performed their fathers church music in liturgical settings. Also performances in Leipzig under Kantor Doles appear to have been limited to such setting. Public concerts with Bach's music outside a liturgical setting were near to non-existent. Four-part chorales published in this period were stripped of their instrumentation and continuo parts, retaining only the four vocal lines.

Classical period

By the time the composers of the classical period, such as Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, encountered Bach's music performance practice had largely changed: keyboard music was performed on the piano, and what little of his vocal music that was still performed was limited to a cappella music. The figured bass was being replaced by written-out scores for all instruments. Bach's larger organ compositions were for the most part untraceable,[7] and likewise his orchestral music and larger vocal compositions remained unperformed.

Performances of Bach's music were mostly limited to private salons such as those of Sarah Itzig Levy and Gottfried van Swieten, where for instance Beethoven played excerpts of the Well-Tempered Clavier. Mozart had arranged some of Bach's music for string trio and quartet. The Sing-Akademie zu Berlin, founded in 1791, included some of Bach's music in their public concerts.

Romantic period

The transformations of the way Bach's music was performed that had taken place in the galant and classical periods were continued in the romantic period: piano instead of harpsichord, motets as a cappella music, etc. With the renewed interest in his larger vocal works and in his orchestral and organ music, also these pieces were adapted to 19th-century performance practices, and contemporary instrumentation.

Felix Mendelssohn performed Bach's music on the organ and conducted the first 19th-century performance of the St Matthew Passion: this 1829 performance set off the Bach Revival. Romantic composers featuring Bach's music in their public performances included Franz Liszt and Carl Tausig.

Arrangements

When the Bach Revival resulted in a higher demand for pieces by Bach to be performed in concerts, these were often presented in an arranged version. Organ music, for instance, could be performed in an orchestral arrangement, or as a bravoura piano piece.[8]

Score publications took into account that the music could be performed on the piano,[9] and various piano arrangements were published, for instance in the Bach-Busoni Editions.

Organ

The build of organs had considerably changed in the 19th century. In the late 19th century André Pirro published his book on Bach's organ music.[10]

Continuo

In the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe, published in the second half of the 19th century, the basso continuo was again rendered as a figured bass. Performance editions, such as those by Robert Franz, expanded the continuo in separate written out parts for multiple instruments. Philipp Spitta, siding with the Bach Ausgabe, disagreed with such overdone expansions of the continuo.

Vocal and instrumental forces

For his 1829 performance of the St Matthew Passion Felix Mendelssohn had produced a performance version of Bach's composition. By this time choirs had more than three or four singers per part, and solo parts were performed by vocal soloists separate from the choir. Also orchestras were larger than the 18 instrumentists Bach mentioned. Some instruments, such as the oboe d'amore, had largely fallen in disuse, or had a modified build compared to the instruments Bach used.

Modern approaches

In the 20th century performances building on the late romantic performance practices for Bach's music remained standard for a long time, including performance of arrangements, but many more ways of performing and presenting Bach's music were added.

In other genres

Bach's music was often adopted in other genres, for instance in Jazz music, by musicians such as Jacques Loussier, Ian Anderson and Uri Caine and the Swingle Singers.

Organ

Harvey Grace described ways of performing Bach's organ music adapted to the possibilities of 20th-century instruments.[11] Such instruments were for instance used by G. D. Cunningham, E. Power Biggs and Albert Schweitzer for their performances of Bach's organ music.

Symphonic arrangements

Edward Elgar, Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy adapted Bach's organ music to full modern symphonic orchestras.

Orchestra, soloists and voices

Orchestral and vocal forces used for performance of Bach's work remained indebted to the romantic tradition for the larger part of the 20th century.

Using modern and alternative instruments

New instruments were deployed for performing Bach's music, for instance performances on the Moog synthesiser by Wendy Carlos.

Historically informed performance practice

When Nikolaus Harnoncourt started adopting the historically informed performance practice he prominently featured Bach's music, such as the Brandenburg Concertos and the cantatas. Performers following in that tradition, such as Gustav Leonhardt, Ton Koopman, Philippe Herreweghe and musicians of the Kuijken family invariably had a large part of their repertoire devoted to Bach.

Voices

Peter Kooy and Dorothee Mields became known for their soloist performances of Bach's vocal music such as his Passions.[12]

Instruments

Wanda Landowska was the first to start performing Bach's keyboard music on harpsichord again. The instrument used by Landowska was however still far from the instruments used in Bach's day.

After performing Bach's music on various organs, Marie-Claire Alain had an instrument built closer to the baroque instruments Bach played.

Ensembles

The size of the ensembles performing Bach's music became smaller again: for instance I Musici started performing baroque music, including Bach's with a smaller ensemble again.

Tempo

Performance tempo generally became more vivid than in the period dominated by the romantic approach to the performance of Bach's music.

References

- 1 2 Johann Adolf Scheibe. pp. 46–47 in Critischer Musicus VI, 14 May 1737.

- ↑ Bach Digital Work 1494 at www

.bachdigital .de - ↑ Bach Digital Work 1172 at www

.bachdigital .de - ↑ Johann Mattheson. Das Beschützte Orchestre, oder desselben Zweyte Eröffnung, footnote p. 222 Hamburg: Schiller, 1717.

- ↑ Spitta, Philipp (1899). Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685–1750 (Volume 3). London: Novello & Co., Appendix XII p. 315

- ↑ Bach, Johann Sebastian. Kurtzer; iedoch höchstnöthiger Entwurff einer wohlbestallten Kirchen Music; nebst einigem unvorgreiflichen Bedencken von dem Verfall derselben. Leipzig: Johann Sebastian Bach, 23 August 1730. Retrieved on 17 May 2011 from http://www.bach.de/leben/kirchenmusik.html.

- ↑ Johann Nikolaus Forkel. Ueber Johann Sebastian Bachs Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke: Für patriotische Verehrer echter musikalischer Kunst. Leipzig: Hoffmeister und Kühnel. 1802, pp. 59–60

- ↑ "Statistik der Concerte im Saale des Gewandhauses zu Leipzig", p. 3, in Dörffel, Alfred (1884). Geschichte der Gewandhausconcerte zu Leipzig vom 25. November 1781 bis 25. November 1881: Im Auftrage der Concert-Direction verfasst. Leipzig.

- ↑ Marx, Adolph Bernhard, editor. Johann Sebastian Bach's noch wenig bekannte Orgelcompositionen: auch am Pianoforte von einem oder zwei Spielern ausführbar. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1833.

- ↑ Pirro, André (1895). L'orgue de Jean-Sébastien Bach. Paris: Fischbacher

- ↑ Grace, Harvey (1922). The Organ Works of Bach. London: Novello & Co

- ↑ Ellen Segeren. "Voor Herreweghe gaat de tijd dringen: 'Ik wil alleen nog topmuziek'", pp. 61–64 in www

.luister , summer 2010.nl