Parliament Act 1911

|

| |

| Long title | An Act to make provision with respect to the powers of the House of Lords in relation to those of the House of Commons, and to limit the duration of Parliament. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 1 & 2 Geo.5 c.13 |

| Territorial extent | United Kingdom |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 18 August 1911 |

| Commencement | 18 August 1911 |

Status: Amended | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

The Parliament Act 1911 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords which make up the Houses of Parliament. This Act must be construed as one with the Parliament Act 1949. The two Acts may be cited together as the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949.[1]

Following the rejection of the 1909 "People's Budget", the House of Commons sought to establish its formal dominance over the House of Lords, who had broken convention in opposing the Bill. The budget was eventually passed by the Lords after the Commons' democratic mandate was confirmed by holding elections in January 1910. The following Parliament Act, which looked to prevent a recurrence of the budget problems, was also widely opposed in the Lords and cross-party discussion failed, particularly because of the proposed Act's applicability to passing an Irish home rule bill. After a second general election in December, the Act was passed with the support of the monarch, George V, who threatened to create sufficient Liberal peers to overcome the then Conservative majority.

The Act effectively removed the right of the Lords to veto money bills completely, and replaced a right of veto over other public bills with a maximum delay of two years. It also reduced the maximum term of a parliament from seven years to five.

Background

Until the Parliament Act 1911, there was no way to resolve contradictions between the two Houses of Parliament except through the creation of additional peers by the Monarch.[2] Queen Anne had created 12 Tory peers to vote through the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713.[3] The Reform Act 1832 was passed when the House of Lords dropped opposition—William IV had threatened to create 80 new peers by request of the Prime Minister, Earl Grey[2]—creating an informal convention that the Lords would give way when the public was behind the House of Commons. For example, Irish Disestablishment, which had been a major bone of contention between the two main parties since the 1830s, was—following intervention by the Queen—passed by the Lords in 1869 after W.E. Gladstone won the 1868 Election on the issue. However, in practice, this gave the Lords a right to demand that such public support was present and to decide the timing of a General Election.[2]

It was the prevailing wisdom that the House of Lords could not amend money bills, since only the House of Commons had the right to decide upon the resources the Monarch could call upon.[2] This did not, however, despite the apparent contradiction, prevent it from rejecting such bills outright.[2] In 1860, with the repeal of the paper duties, all money bills were consolidated into a single budget. This denied the Lords the ability to reject individual components and the prospect of voting down the entire budget was seemingly unpalatable. It was only in 1909 that this became a possibility.[4] Until the Act, the Lords had equal rights over legislation compared to the Commons, but did not utilise its right of veto over financial measures by convention.[5]

There had been an overwhelming Conservative-Unionist majority in the Lords since the Liberal split in 1886.[2] With the Liberal Party attempting to push through significant welfare reforms with considerable popular support, this seemed certain to cause problems in the relationship between the Houses.[2] Between 1906 and 1909, several important measures were being considerably watered down or rejected outright:[6] for example, Birrell introduced the Education Bill 1906, which was intended to address nonconformist grievances arising from the Education Act 1902, but which was amended by the Lords to such an extent that it was effectively a different bill, upon which the Commons dropped the bill.[7] This led to the 26 June 1907 resolution in the House of Commons declaring that the Lords' power should be curtailed, put forward by Liberal Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman.[6][8] In 1909, hoping to force an election,[9] the Lords rejected the financial bill based on the government budget (the "People's Budget") put forward by David Lloyd George,[2] by 350 votes to 75.[10] This, according to the Commons, was "a breach of the Constitution, and a usurpation of the rights of the Commons".[6] The Lords suggested that the Commons justify its position as representing the will of the people: it did this through the January 1910 general election. The Liberal government lost heavily, but remained in majority with the help of a significant number of Irish Nationalist and Labour MPs.[6] The Irish Nationalists saw the continued power of the Lords as detrimental to securing Irish Home Rule.[4] Following the election, the Lords relented on the budget (since reintroduced by the government[6]), it passing the Lords on 28 April, a day after the Commons.[11]

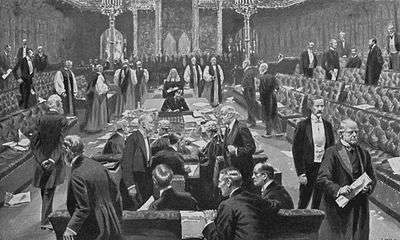

Passage

The Lords was now faced with the prospect of a Parliament Act, which had considerable support from the Irish Nationalists.[4] A series of meetings between the Liberal government and Unionist opposition members was agreed. Twenty-one such meetings were held between 16 June and 10 November.[12] The discussions considered a wide range of proposals, with initial agreement on finance bills and a joint sitting of the House of Commons and Lords as a means by which to enforce Commons superiority in controversial areas; the number of Lords present would be limited such that a Liberal majority of 50 or more in the House of Commons could overrule the Lords.[13] However, the issue of home rule for Ireland was the main contention, with Unionists looking to exempt such a law from the Parliament Act procedure by means of a general exception for "constitutional" or "structural" bills. The Liberals supported an exception for bills relating to the monarchy and Protestant succession, but not home rule.[13] Discussions were declared failed on 10 November.[12]

The government threatened another dissolution if the bill for the Parliament Act were not passed, and followed through on their threat when opposition in the Lords did not diminish. The general election of December produced little change from January.[14] The calling of a second dissolution of parliament now seems to have been contrary to the wishes of Edward VII. Edward had died in May 1910 while the crisis was still in progress. His successor, George V, was asked if he would be prepared to create sufficient peers, which he would only do if the matter arose.[6] This would have meant creating over 400 new Liberal peers.[15] The King did, however, demand that the bill would have to be rejected at least once by the Lords before his intervention.[13] Two amendments made by the Lords were rejected by the Commons, and opposition to the bill showed little sign of reducing. This led Asquith to declare the King's intention to overcome the majority in the House of Lords by creating sufficient new peers.[16] The bill was finally passed in the Lords by 131 votes to 114 votes, a majority of 17.[17] This reflected a large number of abstentions.[18]

Provisions

The preamble included the words "it is intended to substitute for the House of Lords as it at present exists a Second Chamber constituted on a popular instead of hereditary basis, but such substitution cannot be immediately brought into operation" at the request of prominent Cabinet member Sir Edward Grey.[19] The long title of the Act was "An Act to make provision with respect to the powers of the House of Lords in relation to those of the House of Commons, and to limit the duration of Parliament."[20] Section 8 defined the short title as the "Parliament Act 1911".[21]

The bill was also an attempt to place the relationship between the House of Commons and House of Lords on a new footing. As well as the direct issue of money Bills, it set new conventions about how the power the Lords continued to hold would be used.[22] It did not change the composition of the Lords, however.[15]

The Lords would only be able to delay money bills for one month,[23] effectively ending their ability to do so.[15] These were defined as any public bill which contained only provisions dealing with the imposition, repeal, remission, alteration, or regulation of taxation; the imposition for the payment of debt or other financial purposes of charges on the Consolidated Fund, or on money provided by Parliament, or the variation or repeal of any such charges; supply; the appropriation, receipt, custody, issue or audit of accounts of public money; and the raising or guarantee of any loan or the repayment thereof. It did not however, cover any sort of local taxes or similar measures. Some Finance Bills have not fallen within this criterion; Consolidated Fund and Appropriation Bills have. The Speaker of the House of Commons would have to certify that a bill was a money bill, endorsing it with a Speaker's certificate.[15][24] The Local Government Finance Bill 1988, which introduced the Community Charge ("Poll Tax"), was not certified as a Money Bill and was therefore considered by the Lords.[25] Whilst Finance Bills are not considered Money Bills, convention dictates that those parts of a Finance Bill dealing with taxation or expenditure (which, if in an Act alone, would constitute a Money Bill) are not questioned.[26]

Other public bills could no longer be vetoed; instead, they could be delayed for up to two years. This two-year period meant that legislation introduced in the fourth or fifth years of a parliament could be delayed until after the next election, which could prove an effective measure to prevent it being passed.[15] Specifically, two years had to elapse between the second reading in the House of Commons in the first session and the passing of the bill in the House of Commons in the third session.[23] The Speaker has to also certify that the conditions of the bill had been complied with. Significant restrictions on amendments are made to ensure that it is the same bill that has been rejected twice.[27] The 1911 Act made clear that the life of a parliament could not be extended without the consent of the Lords.[28]

Parliament had been limited to a maximum of seven years under the Septennial Act 1715, but this was reduced by the passing of the Parliament Act 1911. Parliament would now be limited to five years, beginning the first meeting of parliament after the election. In practice, no election has been forced by such a limitation as all parliaments have been dissolved by the Monarch on request of the Prime Minister.[29] It should be noted, however, that the five-year maximum duration referred to the lifetime of the Parliament, and not to the interval between General Elections. For example, the 2010 General Election was held five years and one day after the 2005 General Election, whilst the 1992 General Election was held on 9 April 1992 and the next General Election was not held until 1 May 1997. The reduction in parliament length was seen as a counterbalance to the new powers granted to the Commons.[16]

Result

The Lords continued to suggest amendments to money bills over which it had no right of veto and in several instances these were accepted by the Commons. These included the China Indemnity Bill 1925 and the Inshore Fishing Industry Bill 1947.[25] The use of the Lords' now temporary veto remains a powerful check on legislation.[30]

It was used in relation to the Government of Ireland Act 1914, which had been under the threat of a Lords veto, now removed. Ulster Protestants had been firmly against the passing of the bill. However, it never came into force because of the outbreak of the First World War.[31] Amendments to the Parliament Act 1911 were made to prolong the life of the 1910 parliament following the outbreak of the First World War and 1935 parliament because of the Second World War. These made special exemptions to the requirement to hold an election every five years.[32]

Legislation passed through the Parliament Act, without the consent of the Lords, is still considered primary legislation. The importance of this was highlighted in Jackson v Attorney General,[case 1] in which the lawfulness of the Parliament Act 1949 was questioned.[28] The challenge asserted that the 1949 Act was delegated rather than primary legislation, and that the 1911 Act had delegated power to the Commons. If this were the case, then the Commons could not empower itself through the 1949 Act without direct permission from the Lords. Since it was passed under the 1911 Act, the 1949 Act had never received the required consent of the Lords.[33] However, the Judicial Committee of the House of Lords found that the 1949 Act had been lawfully enacted.[28] The 1911 Act, it concluded, was not primarily about empowering the Commons, but rather had the purpose of restricting the ability of the Lords to reject legislation.[33] This ruling also appears to mean that efforts to abolish the House of Lords (a major constitutional change) by using the Act could be successful, although the issue was not directly addressed in the ruling.[34]

Analysis

The Parliament Act 1911 can be seen in the context of the British constitution: rather than creating a written constitution, parliament chose instead to legislate through the usual channels in response to the crisis. This was a pragmatic response, which avoided the further problems of codifying unwritten rules and reconstructing the entire government.[35] It is commonly considered a statute of "constitutional importance", which gives it informal priority in parliament and in the courts with regards to whether later legislation can change it and the process by which this may happen.[36]

It is also mentioned in discussion of constitutional convention. Whilst it replaced conventions regarding the role of the House of Lords, it also relies on several others. Section 1(1) only makes sense if money bills do not arise in the House of Lords and the provisions in section 2(1) only if proceedings on a public bill are completed in a single session, otherwise they must fail and be put through procedure again.[37]

References

Case law

- ↑ Jackson v Attorney General, UKHL 56, [2005] 4 All ER 1253.

Citations

- ↑ The Parliament Act 1949, section 2(2). Digitised copy from the UK Statute Law Database. Accessed on 2 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 203.

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p540

- 1 2 3 Keir (1938). p. 477.

- ↑ Barnett (2002). p. 535.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jackson, Leopold (2001). p. 168.

- ↑ Havighurst, Alfred F., Britain in Transition: The Twentieth Century, University of Chicago Press, 1985, pp. 89–90: see Google Books

- ↑ McKechnie, The reform of the House of Lords

- ↑ Magnus 1964, p534

- ↑ Ensor (1952). p. 417.

- ↑ Ensor (1952). p. 420.

- 1 2 Ensor (1952). p. 422.

- 1 2 3 Ensor (1952). p. 423.

- ↑ Keir (1938). pp. 477–478.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 204.

- 1 2 Keir (1938). p. 478.

- ↑ Joint Committee (2002). Section 6.

- ↑ Jackson, Leopold (2001). p. 169.

- ↑ Ensor (1952). pp. 419–420.

- ↑ "Parliament Act 1911: Introduction". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ↑ "Parliament Act 1911: Section 8". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 27.

- 1 2 Joint Committee (2002). Section 7.

- ↑ "Parliament Act 1911: Section 1". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- 1 2 Barnett (2002). p. 536.

- ↑ Barnett (2002). p. 494–495.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 205.

- 1 2 3 Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 68.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 153.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 40.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 57.

- 1 2 Barnett, Jago (2011). p. 445.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). p. 74.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Bradley, Ewing (2007). pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Jaconelli, Joseph (2005). "Do Constitutional Conventions Bind?". Cambridge Law Journal. 64: 149. doi:10.1017/s0008197305006823.

Sources

- "Joint Committee on House of Lords Reform First Report". parliament.co.uk. HMSO. 2002. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- "HOUSE of LORDS - BRIEFING - REFORM AND PROPOSALS FOR REFORM SINCE 1900". parliament.co.uk. 2000.

- Barnett, Hilaire (2002). Constitutional and Administrative Law (3rd ed.). London: Cavendish Pub Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85941-721-8.

- Barnett, Hilaire; Jago, Robert (2011). Constitutional & Administrative Law (8th ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-57881-7.

- Ensor, R. C. K. (1952). England 1870–1914. The Oxford History of England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 5079147.

- Bradley, A. W.; Ewing, K. D. (2007). Constitutional and Administrative Law (14th ed.). Harlow, United Kingdom: Longman. ISBN 1-4058-1207-9.

- Jackson, Paul; Leopold, Patricia (2001). O. Hood Phillips & Jackson: Constitutional and Administrative Law (8th ed.). London: Sweet and Maxwell. ISBN 0-421-57480-1.

- Keir, David L. (1938). The Constitutional History of Modern Britain. London: A & C Black. OCLC 463283191.

- Magnus, Philip (1964), King Edward The Seventh, London: John Murray, ISBN 0140026584

- McKechnie, William Sharp, 1909: The Reform of the House of Lords

.svg.png)