Compass (drawing tool)

A pair of compasses, also known simply as a compass, is a technical drawing instrument that can be used for inscribing circles or arcs. As dividers, they can also be used as tools to measure distances, in particular on maps. Compasses can be used for mathematics, drafting, navigation, and other purposes.

Compasses are usually made of metal or plastic, and consist of two parts connected by a hinge which can be adjusted to allow the changing of the radius of the circle drawn. Typically one part has a spike at its end, and the other part a pencil, or sometimes a pen.

Prior to computerization, compasses and other tools for manual drafting were often packaged as a "bow set"[1] with interchangeable parts. Today these facilities are more often provided by computer-aided design programs, so the physical tools serve mainly a didactic purpose in teaching geometry, technical drawing, etc.

Construction and parts

Compasses are usually made of metal or plastic, and consist of two parts connected by a hinge which can be adjusted to allow the changing of the radius of the circle drawn. Typically one part has a spike at its end, and the other part a pencil, or sometimes a pen.

Handle

The handle is usually about half an inch long. Users can grip it between their pointer finger and thumb.

Legs

There are two types of legs in a pair of compasses: the straight or the steady leg and the adjustable one. Each has a separate purpose; the steady leg serves as the basis or support for the needle point, while the adjustable leg can be altered in order to draw different sizes of circles.

Hinge

The screw on your hinge holds the two legs in its position; the hinge can be adjusted depending on desired stiffness. The tighter the screw the better the compass’ performance.

Needle point

The needle point is located on the steady leg, and serves as the center point of circles that are drawn.

Pencil lead

The pencil lead draws the circle on a particular paper or material.

Adjusting nut

This holds the pencil lead or pen in place.

Uses

Circles can be made by fastening one leg of the compasses into the paper with the spike, putting the pencil on the paper, and moving the pencil around while keeping the hinge on the same angle. The radius of the circle can be adjusted by changing the angle of the hinge.

Distances can be measured on a map using compasses with two spikes, also called a dividing compass. The hinge is set in such a way that the distance between the spikes on the map represents a certain distance in reality, and by measuring how many times the compasses fit between two points on the map the distance between those points can be calculated.

To use a pair of compasses, place the points on a ruler and open it to the measurement of ½ of the measurement of the circle that is desired. For instance, if one desires to draw a 3 inch (7.6 cm) circle, they must open the compass to 1.5 inches (3.8 cm). Next, place the point (needle) on the spot that you wish the center of your circle to be, and then rotate the section that has the pencil lead around the point, using the handle.

Compasses and straightedge

Compasses-and-straightedge constructions are used to illustrate principles of plane geometry. Although a real pair of compasses is used to draft visible illustrations, the ideal compass used in proofs is an abstract creator of perfect circles. The most rigorous definition of this abstract tool is the "collapsing compass"; having drawn a circle from a given point with a given radius, it disappears; it cannot simply be moved to another point and used to draw another circle of equal radius (unlike a real pair of compasses). Euclid showed in his second proposition (Book I of the Elements) that such a collapsing compass could be used to transfer a distance, proving that a collapsing compass could do anything a real compass can do.

Variants

A beam compass is an instrument with a wooden or brass beam and sliding sockets, or cursors, for drawing and dividing circles larger than those made by a regular pair of compasses.[2]

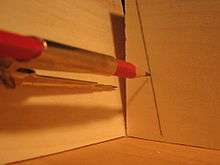

Scribe-compasses[3] is an instrument used by carpenters and other tradesmen. Some compasses can be used to scribe circles, bisect angles and in this case to trace a line. It is the compass in the most simple form. Both branches are crimped metal. One branch has a pencil sleeve while the other branch is crimped with a fine point protruding from the end. The wing nut serves two purposes, first it tightens the pencil and secondly it locks in the desired distance when the wing nut is turned clockwise.

Loose leg wing dividers[4] are made of all forged steel. The pencil holder, thumb screws, brass pivot and branches are all well built. They are used for scribing circles and stepping off repetitive measurements[5] with some accuracy.

A proportional compass, also known as a military compass or sector, was an instrument used for calculation from the end of the sixteenth century until the nineteenth century. It consists of two rulers of equal length joined by a hinge. Different types of scales are inscribed on the rulers that allow for mathematical calculation.

As a symbol

A pair of compasses is often used as a symbol of precision and discernment. As such it finds a place in logos and symbols such as the Freemasons' Square and Compasses and in various computer icons. English poet John Donne used the compass as a conceit in "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning" (1611).

Compass for tracing a line.

Compass for tracing a line. Flat branch, pivot wing nut, pencil sleeve branch of the scribe-compass.

Flat branch, pivot wing nut, pencil sleeve branch of the scribe-compass. 6 inch (15 cm) dividers made from forged steel.

6 inch (15 cm) dividers made from forged steel. One type of sector.

One type of sector. A compass on the Coat of Arms of East Germany (German Democratic Republic).

A compass on the Coat of Arms of East Germany (German Democratic Republic). The compass is a Masonic symbol that appears on jewellery such as this pendant.

The compass is a Masonic symbol that appears on jewellery such as this pendant.

See also

References

- ↑ a current vendor's product

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Beam-Compasses". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (first ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). "Beam-Compasses". Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (first ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

- ↑ Fine Woodworking, Build a Fireplace Mantel, Mario Rodriquez, pgs. 73, 75, The Taunton Press, No. 184, June 2006

- ↑ The Carpenter's Manifesto, Jeffrey Ehrlich & Marc Mannheimer, Holt, Rhinehart & Winston, pg. 64, 1977

- ↑ Fine Woodworking, Laying out dovetails, Chris Gochnour, pg. 31, The Taunton Press, No. 190, April 2007

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Beam or trammel compass (variant form)