Olive production in Palestine

Olive trees are a major agricultural crop in the Palestinian territories, where they are mostly grown for olive oil production. It has been estimated that olive production accounted for 57% of cultivated land in the OPt with 7.8 million fruit-bearing olive trees in 2011.[1] In 2014, an estimated 108,000 tonnes of olives were pressed producing 24,700 tonnes of olive oil - which contributed US $10.9 million in added value to the crop.[2] Around 100,000 households rely on olives for their primary income.[3]

The olive tree is seen by many Palestinians as being a symbol of nationality and connection to the land,[4] particularly due to their slow growth and longevity.

The destruction of Palestinian Olive trees has become a feature of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, with regular reports of damage by Israeli settlers.[5]

History

Olive trees have been cultivated in the region for many thousands of years, with some evidence of olive groves and olive oil technologies dating to the Chalcolithic period, between 3600-3300 BCE.[6][7] Later in the Bronze Age, olive fruits were widely traded as shown by the Uluburun shipwreck - which may have been carrying an olive shipment from Palestine.[7]

Olives and olive oil had a significant role in all of the major religions which developed in the region. In the Jewish scriptures, olives were seen as part of the blessings of the promised land and were a symbol of prosperity. In the New Testament, the Mount of Olives has an important role and the anointing with oil is part of Christian[7] and Islamic religious practice.[8]

In the period between 1700 and 1900, the area around Nablus had developed to be the major area for olive production,[9] and the olive oil was used in lieu of money. The oil was stored in deep wells in the ground in the city and surrounding villages which was then used by merchants to make payments.[9]

By the late 19 century, cash crops in the region were being rapidly expanded to the extent that by 1914 there were 475 thousand dunam of olive groves (about 47.5 thousand hectares or 112 thousand acres) across the area that is now Israel and the Palestinian territories.[10]

In the late Ottoman period before the First World War, olive oil produced near Nablus was hard to export due to its relatively high acidity, high price and limited shelf-life.[11]

During the British Mandate era, production of olives more than doubled from the 1920s to the 1940s.[12]

Production

The vast majority of the olive harvest is pressed in the West Bank mostly around the town of Jenin where most of the olive oil presses are located.[2]

Olive oil produced in Palestine is primarily consumed locally.[13] The natural olive tree cycle of high-yield years followed by low-yield years has caused large fluctuations in production, but on average there is an excess of around 4,000 tonnes of olive oil produced per year. Of this, the biggest market is likely to be to Israel - although the data is not collected, making the destination of the oil hard to assess. The rest is exported to Europe, North America and the Gulf states.[13] The International Olive Council estimates that the average production of Palestinian olive oil was 22,000 tonnes per year with 6,500 tonnes exported in 2014/15.[14]

| Palestinian olive press statistics 2014[2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total olives/ tonnes | Total olive oil pressed/ tonnes | Total added value/ million US $ | |

| Palestine | 108379.1 | 24758.2 | 10.9 |

| West Bank | 88356.4 | 21241.5 | 9.1 |

| Gaza | 20022.6 | 3517.0 | 1.8 |

Agronomy

The main olive cultivars used in the Palestinian territories are Chemlali, Jebbah, K18, Manzolino, Nabali Baladi, Nabali Mohassan, Shami and Souri.[15] Molecular characterisation of Nabali Baladi, Nabali Mohassan and Surri cultivars from olive trees growing in the West Bank has shown that they are true cultivars with measurable differences.[16]

Culture

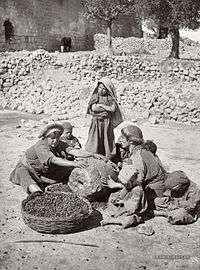

Olive trees are seen as being a major component of traditional Palestinian farming life, with several generations of families gathering together to harvest the olives for two months from mid-September.[17] The harvest season is often associated with celebration for these families, and family and local community celebrations are organised with traditional Palestinian folk music and dancing.[17]

References

- ↑ The Besieged Palestinian Agricultural Sector (PDF). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development - UNCTAD. 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Main Economic Indicators for Olive Presses Activity in Palestine by Governorate, 2014". Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ Lodolini, E.M.; Ali, S.; Mutawea, M.; Qutub, M.; Arabasi, T.; Pierini, F.; Neri, D. (2014). "Complementary irrigation for sustainable production in olive groves in Palestine". Agricultural Water Management. 134: 104–109. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2013.12.006. ISSN 0378-3774.

- ↑ Barbara Rose Johnston; Lisa Hiwasaki; Irene J. Klaver (21 December 2011). Water, Cultural Diversity, and Global Environmental Change: Emerging Trends, Sustainable Futures?. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 496–. ISBN 978-94-007-1773-2.

- ↑ Bowen, Jeremy (2014). "Israel and the Palestinians: A conflict viewed through olives". BBC. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ Liphschitz, Nili; Gophna, Ram; Hartman, Moshe; Biger, Gideon (1991). "The beginning of olive (olea europaea) cultivation in the old world: A reassessment". Journal of Archaeological Science. 18 (4): 441–453. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(91)90037-P. ISSN 0305-4403.

- 1 2 3 Kaniewski, David; Van Campo, Elise; Boiy, Tom; Terral, Jean-Frédéric; Khadari, BouchaÏb; Besnard, Guillaume (2012). "Primary domestication and early uses of the emblematic olive tree: palaeobotanical, historical and molecular evidence from the Middle East". Biological Reviews. 87 (4): 885–899. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00229.x. ISSN 1464-7931.

- ↑ Viktoria Hassouna (2010). Virgin Olive Oil. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-3-8391-7505-7.

- 1 2 Beshara Doumani (12 October 1995). Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900. University of California Press. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-520-91731-6.

- ↑ Dāwid Qûšnêr (1986). Palestine in the Late Ottoman Period: Political, Social, and Economic Transformation. BRILL. pp. 195–. ISBN 90-04-07792-8.

- ↑ Mustafa Abbasi; Ami Ayalo; David De Vries (1 August 2011). Haifa Before & After 1948: Narratives of a Mixed City: Part 1. Institute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-90-8979-092-7.

- ↑ Charles S. Kamen (15 July 1991). Little Common Ground: Arab Agriculture and Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 1920-1948. University of Pittsburgh Pre. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-0-8229-7672-1.

- 1 2 The State of Palestine National Export Strategy: Olive Oil (PDF). ITC and Paltrade. 2014.

- ↑ "World Olive Oil Figures". International Olive Council. 2015.

- ↑ Qutub, M; Ali, S; Mutawea, M; et al. (2010). Characterisation of the Main Palestinian olive cultivars and olive oil (PDF). Paltrade. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ Obaid, Ramiz; Abu-Qaoud, Hassan; Arafeh, Rami (2014). "Molecular characterization of three common olive (Olea europaeaL.) cultivars in Palestine, using simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers". Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 28 (5): 813–817. doi:10.1080/13102818.2014.957026. ISSN 1310-2818.

- 1 2 Darweish, M (2012). "Chapter 13: Olive Trees: Livelihoods and Resistance". In Özerdem, A; Roberts, R. Challenging post-conflict environments : sustainable agriculture. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate. pp. 175–188. ISBN 9781409434825.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olives in Palestine. |