Olaf II of Norway

| Olaf II | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coin of Olaf dated 1023–28. | |||||||||

| King of Norway | |||||||||

| Reign | 1015 – 1028 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Sweyn Forkbeard | ||||||||

| Successor | Cnut the Great | ||||||||

| Born |

995 Ringerike, Norway | ||||||||

| Died |

29 July 1030 (aged 34–35)

| ||||||||

| Spouse | Astrid Olofsdotter | ||||||||

| Issue |

Magnus, King of Norway Wulfhild, Duchess of Saxony | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| House | St. Olaf | ||||||||

| Father | Harald Grenske | ||||||||

| Mother | Åsta Gudbrandsdatter | ||||||||

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity | ||||||||

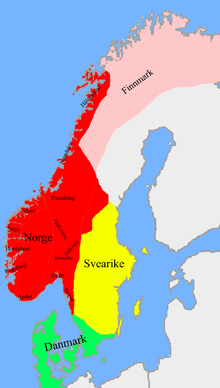

Olaf II Haraldsson (995 – 29 July 1030), later known as St. Olaf (and traditionally as St. Olave), was King of Norway from 1015 to 1028. He was posthumously given the title Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae (English: Eternal/Perpetual King of Norway) and canonised in Nidaros (Trondheim) by Bishop Grimkell, one year after his death in the Battle of Stiklestad on 29 July 1030. His remains were enshrined in Nidaros Cathedral, built over his burial site.

Olaf's local canonisation was in 1164 confirmed by Pope Alexander III, making him a universally recognised saint of the Roman Catholic Church, and a commemorated historical figure among some members of the Anglican Communion.[1] He is also a canonised saint of the Eastern Orthodox Church (feast day celebrated July 29 (translation August 3)) and one of the last famous Western saints before the Great Schism.[2] The exact position of Saint Olaf's grave in Nidaros has been unknown since 1568, due to the Lutheran iconoclasm in 1536–37. Saint Olaf is symbolised by the axe in Norway's coat of arms, and the Olsok (29 July) is still his day of celebration. Many Christian institutions with Scandinavian links and Norway's Order of St. Olav, are named after him.

Modern historians generally agree that Olaf was inclined to violence and brutality, and they accuse earlier scholars of neglecting[3] this side of Olaf's character. Especially during the period of Romantic Nationalism, Olaf was a symbol of national independence and pride, presented to suit contemporary attitudes.

Name

Olaf II's Old Norse name is Ólafr Haraldsson. During his lifetime he was known as Olaf 'the fat' or 'the stout' or simply as Olaf 'the big' (Ólafr digri; Modern Norwegian Olaf digre).[4] In Norway today, he is commonly referred to as Olav den hellige (Bokmål; Olaf the Holy) or Heilage-Olav (Nynorsk; the Holy Olaf) in honour of his sainthood.[5]

Olaf Haraldsson had the given name Óláfr in Old Norse. (Etymology: Anu – "forefather", Leifr – "heir".) Olav is the modern equivalent in Norwegian, formerly often spelt Olaf. His name in Icelandic is Ólafur, in Faroese Ólavur, in Danish Oluf, in Swedish Olof. Olave was the traditional spelling in England, preserved in the name of medieval churches dedicated to him. Other names, such as Oláfr hinn helgi, Olavus rex, and Olaf are used interchangeably (see the Heimskringla of Snorri Sturluson). He is sometimes referred to as Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae (English: Norway's Eternal King), a designation which goes back to the thirteenth century. The term Ola Nordmann as epithet of the archetypal Norwegian may originate in this tradition, as Olav was for centuries the most common male name in Norway.

Background

Olaf was born in Ringerike.[6] His mother was Åsta Gudbrandsdatter, and his father was Harald Grenske, great-great-grandchild of Harald Fairhair, the first king of Norway. Harald Grenske died when Åsta Gudbrandsdatter was pregnant with Olaf. She later married Sigurd Syr, with whom she had other children including Harald Hardrada, who would reign as a future king of Norway.

Saga Sources for Olaf Haraldsson

There are many texts giving information concerning Olaf Haraldsson. The oldest source that we have is the Glælognskviða or "Sea-Calm Poem", composed by Þórarinn loftunga, an Icelander. It praises Olaf and mentions some of the famous miracles attributed to him. Olaf is also mentioned in the Norwegian synoptic histories. These include the Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum (c. 1190), the Historia Norwegiae (c. 1160-1175) and a Latin text, Historia de Antiquitate Regum Norwagiensium by Theodoric the Monk (c. 1177-1188).[7]

Icelanders also wrote extensively about Olaf and we also have several Icelandic sagas about him. These include: Fagrskinna (c. 1220) and Morkinskinna (c. 1225-1235). The famous Heimskringla (c. 1225), written by Snorri Sturluson, largely bases its account of Olaf on the earlier Fagrskinna. We also have the important Oldest Saga of St. Olaf (c. 1200), which is important to scholars for its constant use of skaldic verses, many of which are attributed to Olaf himself.[7]

Finally, there are many hagiographic sources describing St. Olaf, but these focus mostly on miracles attributed to him and cannot be used to accurately recreate his life. A notable one is The Passion and the Miracles of the Blessed Olafr.[8]

Reign

A widely used account of Olaf's life is found in Heimskringla from c. 1225. Although its facts are dubious, the saga recounts Olaf's deeds as follows.

About 1008, Olaf landed on the Estonian island of Saaremaa (Osilia). The Osilians, taken by surprise, had at first agreed to pay the demands made by Olaf, but then gathered an army during the negotiations and attacked the Norwegians. Olaf nevertheless won the battle.[9]

Olaf sailed to the southern coast of Finland sometime in 1008 to plunder.[10][11][12] The journey resulted in the Battle at Herdaler where Olaf and his men were eventually ambushed in the woods. Olaf lost a lot of men but made it back to his boats. He ordered his ships to take off even though a storm was rising. Finns started a pursuit and made the same progress on land as Olaf and his men made with ships. Despite these events they eventually survived. The exact location of the battle is uncertain and the Finnish equivalent for the place Herdaler is not known. It is suggested that the place could be Uusimaa region of Finland.

As a teenager he went to the Baltic, then to Denmark and later to England. Skaldic poetry suggests he led a successful seaborne attack which pulled down London Bridge, though this is not confirmed by Anglo-Saxon sources. This may have been in 1014, restoring London and the English throne to Æthelred the Unready and removing Canute.[13]

Olaf saw it as his call to unite Norway into one kingdom, as his ancestor Harald Fairhair had largely succeeded in doing. On the way home he wintered with Duke Richard II of Normandy. This region had been conquered by Norsemen in the year 881. Duke Richard was himself an ardent Christian, and the Normans had also previously converted to Christianity. Before leaving, Olaf was baptised in Rouen[6] in the pre-romanesque Notre-Dame Cathedral by the Norman duke's own brother Robert the Dane, archbishop of Normandy.

Olaf returned to Norway in 1015 and declared himself king, obtaining the support of the five petty kings of the Uplands. In 1016 at the Battle of Nesjar he defeated Earl Sweyn, one of the earls of Lade and hitherto the virtual ruler of Norway. He founded the town of Borg, later to be known as Sarpsborg, by the waterfall Sarpsfossen in Østfold county. Within a few years he had won more power than had been enjoyed by any of his predecessors on the throne.

He had annihilated the petty kings of the South, subdued the aristocracy, asserted his suzerainty in the Orkney Islands, and conducted a successful raid on Denmark. He made peace with King Olof Skötkonung of Sweden through Þorgnýr the Lawspeaker, and was for some time engaged to Olof's daughter, Princess Ingegerd, though without Olof's approval.

In 1019 Olaf married Astrid Olofsdotter, Olof's illegitimate daughter and the half-sister of his former fiancée. Their daughter Wulfhild married Ordulf, Duke of Saxony, in 1042. Numerous royal, grand ducal and ducal lines are descended from Ordulf and Wulfrid, including the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Maud of Wales, daughter of King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, was the mother of King Olav V of Norway, so Olav and his son Harald V, the present king of Norway, are thus descended from Olaf.

Peter Nicolai Arbo (1859)

But Olaf's success was short-lived. In 1026 he lost the Battle of the Helgeå, and in 1029 the Norwegian nobles, seething with discontent, supported the invasion of King Canute the Great of Denmark. Olaf was driven into exile in Kievan Rus.[6] He stayed for some time in Sweden in the province of Nerike where, according to local legend, he baptised many locals. In 1029, Canute's Norwegian regent, Jarl Håkon Eiriksson, was lost at sea. Olaf seized the opportunity to win back the kingdom, but he fell in 1030 at the Battle of Stiklestad, where some of his own subjects from central Norway took arms against him.

Canute, though distracted by the task of governing England, managed to rule Norway for five years after Stiklestad, with his son Svein and Svein's mother Ælfgifu (known as Álfífa in Old Norse sources) as regents. However, their regency was unpopular, and when Olaf's illegitimate son Magnus (dubbed 'the Good') laid claim to the Norwegian throne, Svein and Ælfgifu were forced to flee.

Problems of Olaf as Christianising king

Traditionally, Olaf has been seen as leading the Christianisation of Norway. However, most scholars of the period now recognise that Olaf himself had little to do with the Christianisation process. Olaf brought with him Grimkell, who is usually credited with helping Olaf create episcopal sees and further organising the Norwegian church. Grimkell, however, was only a member of Olaf’s household and no permanent sees were created until c. 1100. Also, Olaf and Grimkell most likely did not introduce new ecclesiastical laws to Norway, but these were ascribed to Olaf at a later date. Olaf most likely did try to bring Christianity to the interior of Norway, where it was less prevalent.[14]

Also, questions have been raised about the nature of Olaf’s Christianity itself. It seems that Olaf, like many Scandinavian kings, used his Christianity to gain more power for the monarchy and centralise control in Norway. The skaldic verses attributed to Olaf do not speak of Christianity at all, but in fact use pagan references to describe romantic relationships and in some cases, this being because Olaf likely had many wives.[7]

Anders Winroth, in his book The Conversion of Scandinavia, tries to make sense of this problem by arguing that there was a “long process of assimilation, in which the Scandinavians adopted, one by one and over time, individual Christian practices.”[15] Winroth certainly does not say that Olaf was not Christian, but he argues that we cannot think of any Scandinavians as quickly converting in a full way as portrayed in the later hagiographies or sagas. Olaf himself is portrayed in later sources as a Saintly miracle-working figure to help support this quick view of conversion for Norway, although the historical Olaf did not act this way, as seen especially in the skaldic verses attributed to him.

Sainthood

Olaf swiftly became Norway's patron saint; his canonisation was performed only a year after his death by Bishop Grimkell. The cult of Olaf not only unified the country, it also fulfilled the conversion of the nation, something for which the king had fought so hard.

Owing to Olaf's later status as the patron saint of Norway, and to his importance in later medieval historiography and in Norwegian folklore, it is difficult to assess the character of the historical Olaf. Judging from the bare outlines of known historical facts, he appears, more than anything else, as a fairly unsuccessful ruler, whose power was based on some sort of alliance with the much more powerful King Canute the Great; who was driven into exile when he claimed power of his own; and whose attempt at a reconquest was swiftly crushed.

This calls for an explanation of the status he gained after his death. Three factors are important: the later myth surrounding his role in the Christianisation of Norway, the various dynastic relationships among the ruling families, and the need for legitimisation in a later period.[16]

Conversion of Norway

Olaf Haraldsson and Olaf Tryggvason together are traditionally regarded as the driving forces behind Norway's final conversion to Christianity.[17] However, large stone crosses and other Christian symbols suggest that at least the coastal areas of Norway were deeply influenced by Christianity long before Olaf's time; with one exception, all the rulers of Norway back to Håkon the Good (c. 920–961) had been Christians; and Olaf's main opponent, Canute the Great, was a Christian ruler. What seems clear is that Olaf made efforts to establish a church organization on a broader scale than before, among other things by importing bishops from England, Normandy and Germany, and that he tried to enforce Christianity also in the inland areas, which had the least communication with the rest of Europe, and which economically were more strongly based on agriculture, so that the inclination to hold on to the former fertility cult would have been stronger than in the more diversified and expansive western parts of the country.

Many believe Olaf introduced Christian law into the country in 1024, based upon the writing of the Kuli stone. This stone, however, is hard to interpret and we cannot be entirely sure what the stone is referring to.[15] In any case, the codification of Christianity as the legal religion of Norway was attributed to Olaf, and his legal arrangements for the Church of Norway came to stand so high in the eyes of the Norwegian people and clergy that when Pope Gregory VII attempted to make clerical celibacy binding on the priests of Western Europe in 1074–75, the Norwegians largely ignored it, since there was no mention of clerical celibacy in Olaf's legal code for their Church. Only after Norway was made a metropolitan province with its own archbishop in 1153 — which made the Norwegian church, on the one hand, more independent of its king, but, on the other hand, more directly responsible to the Pope — did canon law gain a greater prominence in the life and jurisdiction of the Norwegian church.

Sigrid Undset noted that Olaf was baptised in Rouen, the capital of Normandy, and suggested that Olaf used priests of Norman descent for his missionaries. These priests would be of Norse heritage, could speak the language, and shared the culture of the people they were to convert. Since the Normans themselves had only been in Normandy for about two generations, these priests might, at least in some cases, be distant cousins of their new parishioners and thus less likely to be killed when Olaf and his army departed. The few surviving manuscripts and the printed missal used in the Archdiocese of Nidaros show a clear dependence on the missals used in Normandy.

It should be mentioned that King Olaf II's attempts to convert Norway involved coercion and violence, as described in the Heimskringla and other sources.

Olaf's dynasty

For various reasons, most importantly the death of King Canute the Great in 1035, but perhaps even a certain discontent among Norwegian nobles with the Danish rule in the years after Olaf's death in 1030, his illegitimate son with the concubine Alvhild, Magnus the Good, assumed power in Norway, and eventually also in Denmark. Numerous churches in Denmark were dedicated to Olaf during his reign, and the sagas give glimpses of similar efforts to promote the cult of his deceased father on the part of the young king. This would become typical in the Scandinavian monarchies. It should be remembered that in pagan times the Scandinavian kings derived their right to rule from their claims of descent from the Norse god Odin, or in the case of the kings of the Swedes at Old Uppsala, from Freyr. In Christian times this legitimation of a dynasty's right to rule and its national prestige would be based on its descent from a saintly king. Thus the kings of Norway promoted the cult of St. Olaf, the kings of Sweden the cult of St. Erik and the kings of Denmark the cult of St. Canute, just as in England the Norman and Plantagenet kings similarly promoted the cult of St. Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey, their coronation church.

Saint Olaf

Among the bishops that Olaf brought with him from England, was Grimkell (Latin: Grimcillus). He was probably the only one of the missionary bishops who was left in the country at the time of Olaf's death, and he stood behind the translation and beatification of Olaf on 3 August 1031. Grimkell later became the first bishop of Sigtuna in Sweden.

At this time, local bishops and their people recognised and proclaimed a person a saint, and a formal canonisation procedure through the papal curia was not customary; in Olaf's case, this did not happen until 1888. However Olaf II died before the East-West Schism and a strict Roman Rite was not well-established in Scandinavia at the time; he is venerated also in the Eastern Orthodox Church with great pride by many Orthodox Christians, especially Westerners.[18]

Grimkell was later appointed bishop in the diocese of Selsey in the south-east of England. This is probably the reason why the earliest traces of a liturgical cult of St Olaf are found in England. An office, or prayer service, for St. Olaf is found in the so-called Leofric collectar (c. 1050), which was bequeathed in his last will and testament by Bishop Leofric of Exeter to Exeter Cathedral. This English cult seems to have been short-lived.

Adam of Bremen, writing around 1070, mentions pilgrimage to St. Olaf's shrine in Nidaros, but this is the only firm trace we have of a cult of St. Olaf in Norway before the middle of the twelfth century. By this time he was also being referred to as Norway's Eternal King. In 1152/3, Nidaros was separated from Lund as the archbishopric of Nidaros. It is likely that whatever formal or informal — which, we do not know — veneration of Olaf as a saint there may have been in Nidaros prior to this, was emphasised and formalised on this occasion.

In Þórarinn loftunga's skaldic poem Glælognskviða, or "Sea-Calm Poem", dated to about 1030×34,[19] we hear for the first time of miracles performed by St. Olaf. One is the killing and throwing onto a mountain of a sea serpent still visible on the cliffside.[20] Another took place on the day of his death, when a blind man regained his sight after rubbing his eyes with hands stained with the blood of the saint.

The texts which were used for the liturgical celebration of St. Olaf during most of the Middle Ages were probably compiled or written by Eystein Erlendsson, the second Archbishop of Nidaros (1161–1189). The nine miracles reported in Glælognskviða form the core of the catalogue of miracles in this office.

St. Olaf was widely popular not only in Norway but throughout Scandinavia. Numerous churches in Norway, Sweden, and Iceland were dedicated to him. His presence was even felt in Finland and many traveled from all over the Norse world in order to visit his shrine.[21] Apart from the early traces of a cult in England, there are only scattered references to him outside the Nordic area. Several churches in England were dedicated to him (often as St Olave); the name was presumably popular with Scandinavian immigrants. St Olave's Church, York, is referred to in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 1055[22] as the place of burial of its founder, Earl Siward. This is generally accepted to be the earliest datable church foundation dedicated to Olaf and is further evidence of a cult of St. Olaf in the early 1050s in England. St Olave Hart Street in the City of London is the burial place of Samuel Pepys and his wife. Another St. Olave's Church south of London Bridge gave its name to Tooley Street and to the St Olave's Poor Law Union, later to become the Metropolitan Borough of Bermondsey: its workhouse in Rotherhithe became St Olave's Hospital and then an old-people's home a few hundred metres from St Olav's Church, which is the Norwegian Church in London. It also led to the naming of St Olave's Grammar School, which was established in 1571 and up until 1968 was situated in Tooley Street. In 1968 the school was moved to Orpington, Kent.

St. Olaf was also, together with the Mother of God, the patron saint of the chapel of the Varangians, the Scandinavian warriors who served as the bodyguard of the Byzantine emperor. This church is believed to have been located near the church of Hagia Irene in Constantinople. The icon of the Madonna Nicopeia,[23] presently in St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, which is believed to have been traditionally carried into combat by the Byzantine military forces, is believed to have been kept in this chapel in times of peace. Thus St. Olaf was also the last saint to be venerated by both the Western and Eastern churches before the Great Schism.

There is also a chapel dedicated to St. Olaf in the church of Sant'Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso in Rome. Its altarpiece was a painting of the saint, shown as the Viking king defeating a dragon, the gift presented to Pope Leo XIII in 1893 for the golden jubilee of his ordination as a bishop by his Papal chamberlain, Baron Wilhelm Wedel-Jarlsberg.

San Carlo al Corso may have the only surviving Catholic shrine of St. Olaf outside Norway. In Germany, there used to be a shrine of St. Olaf in Koblenz. It had been installed in 1463 or 1464 by Heinrich Kalteisen, at his retirement home, the Dominican Monastery in the Altstadt ( German, "Old City" ) neighborhood of Koblenz. He had been the Archbishop of Nidaros in Norway for six years, from 1452 to 1458. When he died in 1464, he was buried in front of the shrine's altar.[24] But the shrine did not last. The Dominican Monastery was secularized in 1802 and bulldozed in 1955. Only the Rokokoportal ( "Rococo Portal" ), built in 1754, remains to mark the spot.[25]

Recently the pilgrimage route to Nidaros Cathedral, the site of St. Olaf's tomb, has been reinstated. The route is known as Saint Olav's Way. The main route, which is approximately 640 km long, starts in the ancient part of Oslo and heads North, along Lake Mjosa, up the Gudbrandsdal Valley, over Dovrefjell and down the Orkdal Valley to end at Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim. There is a Pilgrim's Office in Oslo which gives advice to pilgrims, and a Pilgrim Centre in Trondheim, under the aegis of the Cathedral, which awards certificates to successful pilgrims upon the completion of their journey. But the relics of St. Olaf are no longer in the Nidaros Cathedral.

On 29 July, the day of St. Olaf's death, the Faroe Islands celebrate Ólavsøka (Saint Olaf celebration), their National Day, when they remember Saint Olaf, the king who Christianised the islands.[26] The Faroes are the only country to keep this day as a holiday.

Other instances of St. Olaf

.jpg)

- St. Olaf College was founded by Norwegian immigrant Bernt Julius Muus in Northfield, Minnesota, in 1874.

- St. Olav's Cathedral, Oslo, the main cathedral of the Roman Catholic Church in Norway.

- St Olav's Church is the tallest church in Tallinn, Estonia, and between 1549 and 1625 was the tallest building in the world.

- The coat of arms of the Church of Norway contains two axes, the instruments of St. Olaf's martyrdom.

- The oldest picture of St. Olaf is painted on a column in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

- The Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav was founded in 1847 by Oscar I, king of Norway and Sweden, in memory of the king.

- There is a Saint Olaf Catholic Church in downtown Minneapolis.[27]

- There is a Saint Olaf Catholic Church in Norge, Virginia.[28]

- There is a Saint Olaf Catholic Church and School in Bountiful, UT.[29]

- The primary school and GAA club in Balally, Dublin, Ireland are both named for St. Olaf.[30]

- The Tower of St. Olav is the only remaining tower of Vyborg Castle.

- T.S.C Sint Olof is a Dutch student organisation with St. Olaf as its patron.

Ancestors from the sagas

It is unlikely that Olaf II was a (partrilineal) descendant of Harald I.[31] The ancestors in the following family tree must be treated as legendary.

| Ancestry of Olaf II given in the sagas - many connections are dubious | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Legendary Saga of St. Olaf

- Separate Saga of St. Olaf

- Olavinlinna (medieval castle in Savonlinna)

- The Saint Olav Drama

- Ny-Hellesund

- Rauðúlfs þáttr, a short allegorical story involving St. Olaf

- St Olave's Grammar School

- St Olaves, a village in Norfolk, England

- St. Olave's Church (disambiguation)

- St. Olav's Cathedral, Oslo

- Helmet and spurs of Saint Olaf

- Shrine of Manchan, with early representation of St. Olaf

Note

- Eysteinn Erlendsson is commonly believed to have written Et Miracula Beati Olaui. This Latin hagiographical work is about the history and work of St. Olaf, with particular emphasis on his missionary work.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

References

- ↑ http://prayerbook.ca/resources/bcponline/calendar/

- ↑ Vladimir Moss. "MARTYR-KING OLAF OF NORWAY - A Holy Orthodox Saint of Norway". www.orthodox.net. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ – Olav den Hellige var en massemorder

- ↑ Guðbrandur Vigfússon and York Powell, Frederick, ed. (1883). Court Poetry. Corpus Poeticum Boreale. 2. Oxford: Oxford-Clarendon. p. 117. OCLC 60479029.

- ↑ "''St. Olaus, or Olave, King of Norway, Martyr'' (Butler's Lives of the Saints)". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- 1 2 3 "St. Olaf, Patron Saint of Norway", St. Olaf Catholic Church, Minneapolis, Minnesota

- 1 2 3 Lindow, John. "St. Olaf and the Skalds." In: DuBois, Thomas A., ed. Sanctity in the North. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008. 103-127.

- ↑ Kunin, Devra, trans. A History of Norway and The Passion and Miracles of the Blessed Olafr. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 2011.

- ↑ "Saaremaa in written source". Saaremaa.ee. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ↑ "SAGA OF OLAF HARALDSON". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2016-04-30.

- ↑ Gallen, Jarl (1984). Länsieurooppalaiset ja skandinaaviset Suomen esihistoriaa koskevat lähteet. Suomen väestön esihistorialliset juuret. pp. 255–256.

- ↑ edited by Joonas Ahola & Frog with Clive Tolley (2014). Fibula, Fabula, Fact: The Viking Age in Finland. Studia Fennica. p. 422.

- ↑ J. R. Hagland and B. Watson, 'Fact or folklore: the Viking attack on London Bridge', London Archaeologist, 12 (2005), pp. 328–33.

- ↑ Lund, Niels. "Scandinavia, c. 700–1066." The New Cambridge Medieval History. Ed. Rosamond McKitterick. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- 1 2 Winroth, Anders. The Conversion of Scandinavia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

- ↑ "''Olav Haraldsson – Olav the Stout – Olav the Saint'' (Viking Network)". Viking.no. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ↑ Karen Larsen, A History of Norway (Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1948) pp. 95–101.

- ↑ "St. Olaf of Norway". OrthodoxWiki.

- ↑ Margaret Clunies Ross, ' Reginnaglar ', in News from Other Worlds/Tíðendi ór ǫðrum heimum: Studies in Nordic Folklore, Mythology and Culture in Honor of John F. Lindow, ed. by Merrill Kaplan and Timothy R. Tangherlini, Wildcat Canyon Advanced Seminars Occasional Monographs, 1 (Berkeley, CA: North Pinehurst Press, 2012), pp. 3-21 (p. 4); ISBN 0578101742.

- ↑ Serpent image

- ↑ Orrman, Eljas. "Church and society". In: Prehistory to 1520. Ed. Knut Helle. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ↑ "The AngloSaxon Chronicle". Britannia. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ↑ "The invention of tradition". Umbc.edu. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ↑ (Norwegian) Audun Dybdahl, "Henrik Kalteisen", in: Norsk biografisk leksikon [ Norwegian Biographical Dictionary ], retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ↑ See Harald Rausch, "Das Ende der Weißergasse", PAPOO, posted 2 Feb 2011 (German), and Reinhard Schmid, "Koblenz - Dominikanerkloster", Klöster und Stifte in Rheinland-Pfalz [ Monasteries and Churches in Rhineland-Palatinate ] (German) for more details.

- ↑ "''St. Olaf Haraldson'' (Catholic Encyclopedia)". Newadvent.org. 1911-02-01. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ↑ Church website; Statue of the saint from the sanctuary

- ↑ Church website

- ↑ Church website; School website

- ↑ School website; Club website

- ↑ Aschehougs Norgeshistorie, volume 2, p. 92.

Sources

- Ekrem, Inger; Lars Boje Mortensen; Karen Skovgaard-Petersen. Olavslegenden og den Latinske Historieskrivning i 1100-tallets Norge (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2000) ISBN 978-87-7289-616-8

- Hoftun, Oddgeir. Kristningsprosessens og herskermaktens ikonografi i nordisk middelalder (Oslo, 2008) ISBN 978-82-560-1619-8

- Myklebus, Morten. Olaf Viking & Saint (Norwegian Council for Cultural Affairs, 1997) ISBN 978-82-7876-004-8

- Eysteinn Erlendsson, Archbishop of Nidaros; trans. Skard, Eiliv. Passio Olavi: Lidingssoga og undergjerningane åt den Heilage Olav. (Oslo, 1970) ISBN 82-521-4397-0

- Rumar, Lars Helgonet i Nidaros: Olavskult och kristnande i Norden (Stockholm, 1997) ISBN 91-88366-31-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Olaf II of Norway. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Olaf II of Norway. |

- St. Olavs Orden (Norwegian)

- St. Olavsloppet

- A History of Norway and The Miracles of the Blessed Olafr

"Olaf II.". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Olaf II.". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

| Olaf the Saint Cadet branch of the Fairhair dynasty Born: 995 Died: July 29 1030 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Sweyn Forkbeard |

King of Norway 1015–1028 |

Vacant Regency held by Hákon Eiríksson Title next held by Cnut the Great |