Nickel(II) hydroxide

| | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Nickel(II) hydroxide | |

| Other names

Nickel hydroxide, Theophrastite | |

| Identifiers | |

| 12054-48-7 36897-37-7 (monohydrate) | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChemSpider | 55452 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.031.813 |

| EC Number | 235-008-5 |

| PubChem | 61534 |

| RTECS number | QR648000 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Ni(OH)2 | |

| Molar mass | 92.724 g/mol (anhydrous) 110.72 g/mol (monohydrate) |

| Appearance | green crystals |

| Density | 4.10 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 230 °C (446 °F; 503 K) (anhydrous, decomposes) |

| 0.13 g/L | |

| Solubility | soluble in dilute acid, ammonia (monohydrate) |

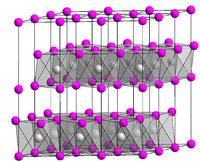

| Structure[1] | |

| hexagonal, hP3 | |

| P3m1, No. 164 | |

| a = 0.3117 nm, b = 0.3117 nm, c = 0.4595 nm α = 90°, β = 90°, γ = 120° | |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S |

79 J·mol−1·K−1[2] |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH |

−538 kJ·mol−1[2] |

| Hazards | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (median dose) |

1515 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Nickel(II) hydroxide is the inorganic compound with the formula Ni(OH)2. It is an apple-green solid that dissolves with decomposition in ammonia and amines and is attacked by acids. It is electroactive, being converted to the Ni(III) oxy-hydroxide, leading to widespread applications in rechargeable battery.[3]

Properties

Nickel(II) hydroxide has two well-characterized polymorphs, α and β. The α structure consists of Ni(OH)2 layers with intercalated anions or water.[4][5] The β form adopts a hexagonal close-packed structure of Ni2+ and OH− ions.[4][5] In the presence of water, the α polymorph typically recrystallizes to the β form.[4][6] In addition to the α and β polymorphs, several γ nickel hydroxides have been described, distinguished by crystal structures with much larger inter-sheet distances.[4]

The mineral form of Ni(OH)2, theophrastite, was first identified in the Vermion region of northern Greece, in 1980. It is found naturally as a translucent emerald-green crystal formed in thin sheets near the boundaries of idocrase or chlorite crystals.[7] A nickel-magnesium variant of the mineral, (Ni,Mg)(OH)2 had been previously discovered at Hagdale on the island of Unst in Scotland.[8]

Reactions

Nickel (II) hydroxide is frequently used in electrical car batteries.[5] Specifically, Ni(OH)2 readily oxidizes to nickel oxyhydroxide, NiOOH, in combination with a reduction reaction, often of a metal hydride (reaction 1 and 2).[9]

Reaction 1 Ni(OH)2 + OH− → NiO(OH) + H2O + e−

Reaction 2 M + H2O + e− → MH + OH−

Net Reaction (in H2O) Ni(OH)2 + M → NiOOH + MH

Of the two polymorphs, α-Ni(OH)2 has a higher theoretical capacity and thus is generally considered to be preferable in electrochemical applications. However, it transforms to β-Ni(OH)2 in alkaline solutions, leading to many investigations into the possibility of stabilized α-Ni(OH)2 electrodes for industrial applications.[6]

Synthesis

The synthesis entails treating aqueous solutions of nickel(II) salts with potassium hydroxide.[10]

Toxicity

The Ni2+ ion is a known carcinogen. Toxicity and related safety concerns have driven research into increasing the energy density of Ni(OH)2 electrodes, such as the addition of calcium or cobalt hydroxides.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Enoki, Toshiaki; Tsujikawa, Ikuji (1975). "Magnetic Behaviours of a Random Magnet, NipMg(1-p)(OH2)". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 39 (2): 317. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.39.317.

- 1 2 Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A22. ISBN 0-618-94690-X.

- 1 2 Chen, J.; Bradhurst, D.H.; Dou, S.X.; Liu, H.K. (1999). "Nickel Hydroxide as an Active Material for the Positive Electrode in Rechargeable Alkaline Batteries". J. Electrochem. Soc. 146 (10): 3606–3612. doi:10.1149/1.1392522.

- 1 2 3 4 Oliva, P.; Leonardi, J.; Laurent, J.F. (1982). "Review of the structure and the electrochemistry of nickel hydroxides and oxy-hydroxides". Journal of Power Sources. 8 (2): 229–255. doi:10.1016/0378-7753(82)80057-8.

- 1 2 3 Jeevanandam, P.; Koltypin, Y.; Gedanken, A. (2001). "Synthesis of Nanosized α-Nickel Hydroxide by a Sonochemical Method". Nano Letters. 1 (5): 263–266. doi:10.1021/nl010003p.

- 1 2 Shukla, A.K.; Kumar, V.G.; Munichandriah, N. (1994). "Stabilized α-Ni(OH)2 as Electrode Material for Alkaline Secondary Cells". J. Electrochem. Soc. 141 (11): 2956–2959. doi:10.1149/1.2059264.

- ↑ Marcopoulos, T.; Economou, M. (1980). "Theophrastite, Ni(OH)2, a new mineral from northern Greece" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 66: 1020–1021.

- ↑ Livingston, A. and Bish, D. L. (1982). "On the new mineral theophrastite, a nickel hydroxide, from Unst, Shetland, Scotland" (PDF). Mineralogical Magazine. 6 (338): 1.

- ↑ Ovshinsky, S.R.; Fetcenko, M.A.; Ross, J. (1993). "A nickel metal hydride battery for electric vehicles". Science. 260 (5105): 176–181. doi:10.1126/science.260.5105.176. PMID 17807176.

- ↑ Glemser, O. (1963) "Nickel(II) Hydroxide" in ""Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd ed. G. Brauer (ed.), Academic Press, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1549.