Negrito

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Religion | |

| Animism, traditional |

.jpg)

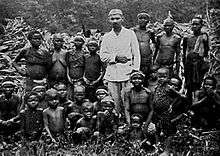

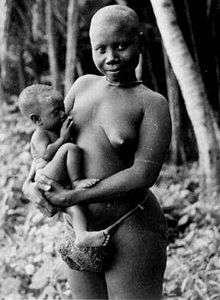

The Negrito (/nɪˈɡriːtoʊ/) are several ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia.[1] Their current populations include Andamanese peoples of the Andaman Islands, Semang peoples of Malaysia, the Mani of Thailand, and the Aeta or Agta, Ati, and 30 other peoples of the Philippines.

The Negrito peoples show strong physical similarities with Negrillos (African Pygmies), but are genetically closer to other Southeast Asian populations. They may be descended from ancient Australoid-Melanesian settlers of Southeast Asia, or represent an early split from the southern coast migrants from Africa.

Etymology

The word "Negrito" is the Spanish diminutive of negro, used to mean "little black person". This usage was coined by 16th-century Spanish missionaries operating in the Philippines, and was borrowed by other European travellers and colonialists across southeast Asia to label various peoples perceived as sharing relatively small physical stature and dark skin.[2] Contemporary usage of an alternative Spanish epithet, Negrillos, also tended to bundle these peoples with the pygmy peoples of Central Africa, based on perceived similarities in stature and complexion.[2] (Historically, the label Negrito has occasionally been used also to refer to African Pygmies.)[3]

Many on-line dictionaries give the plural in English as either "negritos" or "negritoes", without preference. The plural in Spanish is "negritos".[4][5]

The appropriateness of using the label "Negrito" to bundle together peoples of different ethnicity based on similarities in stature and complexion has been challenged.[2]

Origins

Genetics

The (male) Y-DNA haplogroups C-M130, as seen, for example, in the Semang of Malaysia, and D-M174, among Andaman Islanders, are more prominent among Negritos than the general populations surrounding them.[6] Haplogroup O2 is also common among Austroasiatic-speaking Negrito peoples, such as the Maniq (or Mani) of Thailand, and the Semang of Malaysia.

Males from the Aeta people (or Agta) people of The Philippines, are of great interest to genetic, anthropological and historical researchers, as at least 83% of them belong to haplogroup K2b, in the form of its rare primary clades K2b1* and P* (a.k.a K2b2* or P-P295*).[7] Most Aeta males (60%) carry K-P397 (K2b1), which is otherwise uncommon in the Philippines and is strongly associated with the indigenous peoples of Melanesia and Micronesia. Basal P* is rare outside the Aeta and some other groups within Maritime South East Asia.

The use of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) shows the genomes of Andamanese people to be closest to those of South Asians. This suggests a relation between Andaman islanders and South Asians.[8]

Bulbeck (2013) likewise noted that the Andamanese's nuclear DNA clusters with that of other Andamanese Islanders, as they carry Haplogroup D and maternal M (mtDNA) unique to their own.[8] However, this is a subclade of the D haplogroup which has not been seen outside of the Andamans, a fact that underscores the insularity of these tribes.[9] Analysis of mtDNA, which is inherited exclusively by maternal descent, confirms the above results. All Onge belong to M32 mtDNA, subgroup of M, which is unique to Onge people.[10] Their parental Y-DNA is exclusively Haplogroup D, which is also only found in Asia.[11]

A 2010 study by the Anthropological Survey of India and the Texas-based Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research identified seven genomes from 26 isolated "relic tribes" from the Indian mainland, such as the Baiga, which share "two synonymous polymorphisms with the M42 haplogroup, which is specific to Australian Aborigines". These were specific mtDNA mutations that are shared exclusively by Australian aborigines and these Indian tribes, and no other known human groupings.[12]

A study of blood groups and proteins in the 1950s suggested that the Andamanese were more closely related to Oceanic peoples than African Pygmies. Genetic studies on Philippine Negritos, based on polymorphic blood enzymes and antigens, showed they were similar to surrounding Asian populations.[13]

Negrito peoples may descend from Australoid Melanesian settlers of Southeast Asia. Despite being isolated, the different peoples do share genetic similarities with their neighboring populations.[13][14] They also show relevant phenotypic (anatomic) variations which require explanation.[14]

In contrast, a recent genetic study found that unlike other early groups in Malesia, Andamanese Negritos lack the Denisovan hominin admixture in their DNA. Denisovan ancestry is found among indigenous Melanesian and Australian populations between 4–6%.[15][16]

Some studies have suggested that each group should be considered separately, as the genetic evidence refutes the notion of a specific shared ancestry between the "Negrito" groups of the Andaman Islands, the Malay Peninsula, and the Philippines.[17]

Anthropology

A number of features would seem to suggest a common origin for the Negritos and Negrillos (African Pygmies). No other living human population has experienced such long-lasting isolation from contact with other groups.[13]

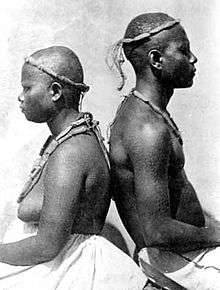

Features of the Negrito include short stature, dark skin, woolly hair, scant body hair, and occasional steatopygia. The claim that the Andamanese more closely resemble African Pygmies than other Asian populations in their cranial morphology in a study of 1973 added some weight to this theory, before genetic studies pointed to a closer relationship with their neighbors.[13]

Multiple studies also show that Negritos from Southeast Asia to New Guinea share a closer cranial affinity with Australo-Melanesians.[18][19]

Historical distribution

Andamese Negrito people

According to both Wells and Mason, the Australoid Negritos, similar to the Andamanese adivasis of today, were the first identifiable human population to colonize India, likely 30–65 thousand years before present (kybp).[20][21] This first colonization of the Indian mainland and the Andaman Islands by humans is theorized to be part of a great coastal migration of humans from Africa along the coastal regions of the Indian mainland and towards Southeast Asia, Japan and Oceania.[20]

The Negrito peoples may be descended from ancient Australoid-Melanesian settlers of Southeast Asia, or represent an early split-off from the earliest Africans who dispersed out of Africa through the southern coastal road. The appropriateness of using the label "Negrito" to bundle together peoples of different ethnicity based on similarities in stature and complexion has been challenged.[22]

Other populations

Negritos may have also lived in Taiwan.[23] The Negrito population shrank to the point that, up to 100 years ago, only one small group lived near the Saisiyat tribe.[23] Evidence of their former habitation is a Saisiyat festival celebrating the black people in a festival called Pas-ta'ai.[23]

Vietnamese people have many racial and ethnic sources, including Austro-Asian, Thai, Chinese and Negrito.[24] Semang Negritos are believed to be descended from Hoabinhian people.[25] Ancient Mongoloid, Negrito, Indonesian, Melanesian, and Australoid remains have been found in Vietnam.[26]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Snow, Philip. The Star Raft: China's Encounter With Africa. Cornell Univ. Press, 1989 (ISBN 0801495830)

- 1 2 3 Manickham, Sandra Khor (2009). "Africans in Asia: The Discourse of 'Negritos' in Early Nineteenth-century Southeast Asia". In Hägerdal, Hans. Responding to the West: Essays on Colonial Domination and Asian Agency. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 69–79. ISBN 978-90-8964-093-2.

- ↑ See, for example: Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, 1910–1911: "Second are the large Negrito family, represented in Africa by the dwarf-races of the equatorial forests, the Akkas, Batwas, Wochuas and others..." (p. 851)

- ↑ "Merriam Webster".

- ↑ "The Free Dictionary".

- ↑ 走向遠東的兩個現代人種

- ↑ ISOGG, 2016, Y-DNA Haplogroup P and its Subclades – 2016 (20 June 2016).

- 1 2 Bulbeck, David (November 2013). "Craniodental Affinities of Southeast Asia's "Negritos" and the Concordance with Their Genetic Affinities". Human Biology. 85 (1): 95–134. doi:10.3378/027.085.0305. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Kumarasamy Thangaraj, Lalji Singh, Alla G. Reddy, V. Raghavendra Rao, Subhash C. Sehgal, Peter A. Underhill, Melanie Pierson, Ian G. Frame, and Erika Hagelberg (2002), Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2008, retrieved 2008-11-16,

Our data indicate that the Andamanese have closer affinities to Asian than to African populations and suggest that they are the descendants of the early Palaeolithic colonizers of Southeast Asia… All Onge and Jarawa had the same binary haplotype D… Great Andaman males had five different binary haplotypes, found previously in Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and Melanesia

- ↑ M. Phillip Endicott; Thomas P. Gilbert; Chris Stringer; Carles Lalueza-Fox; Eske Willerslev; Anders J. Hansen; Alan Cooper (2003), "The Genetic Origins of the Andaman Islanders" (PDF), American Journal of Human Genetics, 72 (1): 178–184, doi:10.1086/345487, PMC 378623

, PMID 12478481, retrieved 2009-04-21

, PMID 12478481, retrieved 2009-04-21 - ↑ Reich, David; Kumarasamy Thangaraj; Nick Patterson; Alkes L. Price; Lalji Singh (24 September 2009). "Reconstructing Indian Population History". Nature. 461 (7263): 489–494. doi:10.1038/nature08365. PMC 2842210

. PMID 19779445.

. PMID 19779445. - ↑ Satish Kumar; Rajasekhara Reddy Ravuri; Padmaja Koneru; BP Urade; BN Sarkar; A Chandrasekar; VR Rao (22 July 2009), "Reconstructing Indian-Australian phylogenetic link", BMC Evolutionary Biology, BioMed Central, 9: 173, doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-173,

In our completely sequenced 966-mitochondrial genomes from 26 relic tribes of India, we have identified seven genomes, which share two synonymous polymorphisms with the M42 haplogroup, which is specific to Australian Aborigines…direct genetic evidence of an early colonization of Australia through south Asia

- 1 2 3 4 Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; et al. (21 January 2003), "Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population" (PDF), Current Biology, 13 (2): 86–93, doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01336-2, PMID 12546781

- 1 2 Stock, JT (2013). "The skeletal phenotype of "negritos" from the Andaman Islands and Philippines relative to global variation among hunter-gatherers". Human Biology. 85 (1-3): 67–94. doi:10.3378/027.085.0304. PMID 24297221.

- ↑ Reich; et al. (2011). "Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 89: 516–28. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005. PMC 3188841

. PMID 21944045.

. PMID 21944045. - ↑ "About 3% to 5% of the DNA of people from Melanesia (islands in the southwest Pacific Ocean), Australia and New Guinea as well as aboriginal people from the Philippines comes from the Denisovans." Oldest human DNA found in Spain – Elizabeth Landau's interview of Svante Paabo, accessdate=2013-12-09

- ↑ Catherine Hill, Pedro Soares, Maru Mormina, Vincent Macaulay, William Meehan, James Blackburn, Douglas Clarke, Joseph Maripa Raja, Patimah Ismail, David Bulbeck, Stephen Oppenheimer, Martin Richards (2006), "Phylogeography and Ethnogenesis of Aboriginal Southeast Asians" (PDF), Molecular Biology and Evolution, Oxford University Press, 23: 2480–91, doi:10.1093/molbev/msl124, PMID 16982817

- ↑ Getting Here: The Story of Human Evolution, William Howells, Compass Press, 1993

- ↑ David Bulbeck, Pathmanathan Raghavan and Daniel Rayner (2006), "Races of Homo sapiens: if not in the southwest Pacific, then nowhere" (PDF), World Archaeology, Taylor & Francis, 38 (1): 109–132, doi:10.1080/00438240600564987, ISSN 0043-8243, JSTOR 40023598

- 1 2 Spencer Wells (2002), The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-11532-X,

…the population of south-east Asia prior to 6000 years ago was composed largely of groups of hunter-gatherers very similar to modern Negritos… So, both the Y-chromosome and the mtDNA paint a clear picture of a coastal leap from Africa to south-east Asia, and onward to Australia… DNA has given us a glimpse of the voyage, which almost certainly followed a coastal route via India

- ↑ Jim Mason (2005), An Unnatural Order: The Roots of Our Destruction of Nature, Lantern Books, ISBN 1-59056-081-7,

Australia's 'aboriginal' peoples are another case in point. At the end of the Ice Age, their homeland stretched from the middle of India eastward into southeast Asia and as far south as Indonesia and nearby islands. As agriculture spread from its centers in southeast Asia, these pre-Australoid forager people moved farther southward to New Guinea and Australia.

- ↑ Manickham 2009.

- 1 2 3 Jules Quartly (27 Nov 2004). "In honor of the Little Black People". Taipei Times. p. 16. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ Chan 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ Bellwoord 1999, p. 286.

- ↑ Vietnam. Bộ ngoại giao 1969, p. 28.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Negritos". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Negritos". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Evans, Ivor Hugh Norman. The Negritos of Malaya. Cambridge [Eng.]: University Press, 1937.

- Garvan, John M., and Hermann Hochegger. The Negritos of the Philippines. Wiener Beitrage zur Kulturgeschichte und Linguistik, Bd. 14. Horn: F. Berger, 1964.

- Hurst Gallery. Art of the Negritos. Cambridge, Mass: Hurst Gallery, 1987.

- Khadizan bin Abdullah, and Abdul Razak Yaacob. Pasir Lenggi, a Bateq Negrito Resettlement Area in Ulu Kelantan. Pulau Pinang: Social Anthropology Section, School of Comparative Social Sciences, Universití Sains Malaysia, 1974.

- Mirante, Edith (2014). The Wind in the Bamboo: Journeys in Search of Asia's 'Negrito' Indigenous Peoples. Bangkok, Orchid Press.

- Schebesta, P., & Schütze, F. (1970). The Negritos of Asia. Human relations area files, 1-2. New Haven, Conn: Human Relations Area Files.

- Armando Marques Guedes (1996). Egalitarian Rituals. Rites of the Atta hunter-gatherers of Kalinga-Apayao, Philippines, Social and Human Sciences Faculty, Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

- Zell, Reg. About the Negritos: A Bibliography. edition blurb, 2011.

- Zell, Reg. Negritos of the Philippines. The People of the Bamboo - Age - A Socio-Ecological Model. edition blurb, 2011.

- Zell, Reg, John M. Garvan. An Investigation: On the Negritos of Tayabas. edition blurb, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Negrito. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Negritos. |

- Negritos of Zambales—detailed book written by an American at the turn of the previous century holistically describing the Negrito culture.

- Andaman.org: The Negrito of Thailand

- Historycooperative.org: Africans and Asians: Historiography and the Long View of Global Interaction

- The Southeast Asian Negrito