Muscular Christianity

Muscular Christianity is a Christian commitment to piety and physical health, basing itself on the New Testament, which sanctions the concepts of character (Philippians 3:14) and well-being (Corinthians1 6:19-20).[1][2][3]

The movement came into vogue during the Victorian era and stressed the need for energetic Christian evangelism in combination with an ideal of vigorous masculinity. Historically, it is most associated with the English writers Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes, and in Canada with Ralph Connor, though the name was bestowed by others. American President Theodore Roosevelt was raised in a household that practiced Muscular Christianity.[4] Roosevelt, Kingsley, and Hughes promoted physical strength and health as well as an active pursuit of Christian ideals in personal life and politics. Muscular Christianity has continued itself through organizations that combine physical and Christian spiritual development.[5] It is influential within both Catholicism and Protestantism.[6][7]

Origins

Muscular Christianity can be traced back to Paul the Apostle, who used athletic metaphors to describe the challenges of a Christian life.[8] However, the explicit advocacy of sport and exercise in Christianity did not appear until 1762, when Rousseau's Emile described physical education as important for the formation of moral character.[9]

The term "Muscular Christianity" became well known in a review by the barrister T. C. Sandars of Kingsley's novel Two Years Ago in the February 21, 1857 issue of the Saturday Review.[8][10] (The term had appeared slightly earlier.)[11] Kingsley wrote a reply to this review in which he called the term "painful, if not offensive",[12] but he later used it favourably on occasion.[13] Hughes used it in Tom Brown at Oxford; saying that it was "a good thing to have muscled, strong and well-exercised bodies," he specified, "The least of the muscular Christians has hold of the old chivalrous and Christian belief, that a man's body is given him to be trained and brought into subjection, and then used for the protection of the weak, the advancement of all righteous causes, and the subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men."[14]

In addition to the beliefs stated above, muscular Christianity preached the spiritual value of sports, especially team sports. As Kingsley said, "games conduce, not merely to physical, but to moral health".[15] An article on a popular nineteenth-century Briton summed it up thus: "John MacGregor is perhaps the finest specimen of muscular Christianity that this or any other age has produced. Three men seemed to have struggled within his breast—the devout Christian, the earnest philanthropist, the enthusiastic athlete."[16]

The idea was controversial. For one example, a reviewer mentioned "the ridicule which the 'earnest' and the 'muscular' men are doing their best to bring on all that is manly", though he still preferred "'earnestness' and 'muscular Christianity'" to eighteenth-century propriety.[17] For another, a clergyman at Cambridge University horsewhipped a friend and fellow clergyman after hearing that he had said grace without mentioning Jesus because a Jew was present.[18] A commentator said, "All this comes, we fear, of Muscular Christianity."[19]

Influence

By 1901, muscular Christianity was influential enough in England that one author could praise "the Englishman going through the world with rifle in one hand and Bible in the other" and add, "If asked what our muscular Christianity has done, we point to the British Empire."[20]

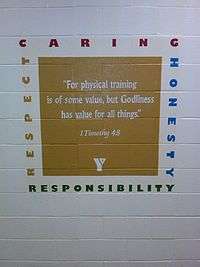

Muscular Christianity spread to other countries in the 19th century. It was well entrenched in Australian society by 1860, though not always with much recognition of the religious element.[23] In the United States it appeared first in private schools and then in the YMCA and in the preaching of evangelists such as Dwight L. Moody.[24] (The addition of athletics to the YMCA led to, among other things, the invention of basketball and volleyball.) Parodied by Sinclair Lewis in Elmer Gantry (though he had praised the Oberlin College YMCA for its "positive earnest muscular Christianity") and out of step with theologians such as Reinhold Niebuhr, its influence declined in American mainline Protestantism. Nonetheless, it was felt in such evangelical organizations as the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, Athletes in Action, and the Promise Keepers.[25]

In the 21st century, the push for a more masculine Christianity has been made by New Calvinist pastors such as John Piper, who claims, "God revealed Himself in the Bible pervasively as king not queen; father not mother. Second person of the Trinity is revealed as the eternal Son not daughter; the Father and the Son create man and woman in His image and give them the name man, the name of the male." Because of this, Piper contends "that God has given Christianity a masculine feel."[26]

In 2012, athletes such as Tim Tebow, Manny Pacquiao, Josh Hamilton, and Jeremy Lin have also exemplified Muscular Christianity through sharing their faith with their fans.[27][28]

See also

- Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle, Sr.

- Biblical patriarchy

- Christian vegetarianism

- Christianity and association football – followers of Muscular Christianity established several of England's leading football teams

- Dominion Theology

- New Testament athletic metaphors

- Pauline Christianity

- Sports ministry

- Muscular Judaism

- Muscular Liberalism

References

- ↑ Marjorie B. Garber (Apr 8, 1998). Symptoms of Culture. Psychology Press.

'I press toward the mark for the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus' (Philippians 3:14) has been described as the verse that has become 'the keystone of muscular Christianity.'

- ↑ David P. Setran (Jan 23, 2007). The college "Y": student religion in the era of secularization. Palgrave Macmillan.

While the shift to a character-oriented evangelism clearly represented muscular Christianity and its desire for 'clean living,' this temper was perhaps even better represented by an equally powerful and increasingly dominant emphasis on 'social evangelism.'

- ↑ Michael S. Kimmel, Amy Aronson (Dec 1, 2003). Men & Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopædia. ABC-CLIO.

Muscular Christianity can be defined as a Christian commitment to health and manliness. Its origins can be traced to the New Testament, which sanctions manly exertion (Mark 11:15) and physical health (1 Cor 6:19–20).

- ↑ Andres, Sean (2014). 101 Things Everyone Should Know about Theodore Roosevelt. Adams Media. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-1440573576.

- ↑ David Yamane, Keith A. Roberts (2012). Religion in Sociological Perspective. Pine Forge Press. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

Muscular Christianity's main focus was to address the concerns of boys directly, not abstractly, so that they could apply religion to their lives. The idea did not catch on quickly in the United States, but over time it has become one of the most notable tools employed in Evangelical Protestant outreach ministries.

- ↑ Alister E. McGrath (2008). Christianity's Dangerous Idea. HarperOne. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

Nor is sport a purely Protestant concern: Catholicism can equally well be said to promote muscular Christianity, at least to some extent, through the athletic programs of such leading schools as the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

- ↑ Michael S. Kimmel; Amy Aronson (2004). Men and Masculinities: a Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopædia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

As neo-orthodoxy arose in the mainline Protestant churches, Muscular Christianity declined there. It did not, however, disappear from American landscape, because it found some new sponsors. In the early 2000s these include the Catholic Church and various rightward-leaning Protestant groups. The Catholic Church promotes Muscular Christianity in the athletic programs of schools such as Notre Dame, as do evangelical Protestant groups such as Promise Keepers, Athletes in Action, and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes.

- 1 2 Watson, Nick J. Muscular Christianity in the modern age. Sport and spirituality (2007), pages 81–82.

Athletic metaphors attributed to Paul: - ↑ Watson, Nick J.; Stuart Weir; Stephen Friend (2005). "The Development of Muscular Christianity in Victorian Britain and Beyond". Journal of Religion & Society. 7: paragraph 7.

- ↑ Ladd, Tony; James A. Mathisen (1999). Muscular Christianity: Evangelical Protestants and the Development of American Sport. Grand Rapids, Mich.: BridgePoint Books. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0-8010-5847-3.

- ↑ Anonymous (December 1852). "Pastoral Theology: Power in the Pulpit". The Eclectic Review. IV: 766. Retrieved 2011-04-19. The article is a review of a book of lectures by the theologian Alexandre Vinet.

- ↑ Watson, Weir, and Friend, paragraph 6.

- ↑ Kingsley, Charles (1889). Letters and Memoirs of His Life, vol. II. Scribner's. p. 54. Quoted by Rosen, David (1994). "The volcano and the cathedral: muscular Christianity and the origins of primal manliness". In Donald E. Hall (ed.). Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-521-45318-6.

- ↑ Chapter 11, quoted by Ladd and Mathisen.

- ↑ Kingsley, Charles (1879). "Nausicaa in London: or, The Lower Education of Women". Health and Education (1887 ed.). Macmillan and Co. p. 86. Retrieved 2011-06-13. Quoted by Ladd and Mathisen).

- ↑ Anonymous (1895). "'Rob Roy' MacGregor". The London Quarterly and Holborn Review. 84: 71–86. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- ↑ "Reviews: Essays Sceptical and Anti-Sceptical on Problems Neglected or Misconceived, by Thomas DeQuincey". The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Science, and Art (2159): 538–540. June 5, 1958. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ↑ "News of the Week". The Spectator. 34 (1702): 124. Feb 9, 1861. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ↑ "Argumentum Baculinum". The Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art. 11 (276): 141–142. Feb 9, 1861. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ↑ Cotton Minchin, J. G. (1901). Our Public Schools: Their Influence on English History; Charter House, Eton, Harrow, Merchant Taylors', Rugby, St. Paul's Westminster, Winchester. Swan Sonnenschein & Co. p. 113. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ↑ McNeil, Harold (2010-11-20). "The faith behind football: Bills players talk to city's youth about God's role in their success". The Buffalo News. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ↑ Major, Andy (2010-01-05). "George Wilson wins Walter Payton Man of the Year". The Official Website of the Buffalo Bills. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ↑ Brown, David W. (1986). "Muscular Christianity in the Antipodes: Some Observations on the Diffusion and Emergence of a Victorian Ideal in Australian Social Theory" (PDF). Sporting Traditions: The Journal of the Australian Society for Sports History. 4. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- ↑ Heather, Hendershot (2004). Shaking the World for Jesus: Media and Conservative Evangelical Culture. University of Chicago Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-226-32679-9.

- ↑ Putney, Clifford (2001). Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880–1920. Harvard University Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 0-674-01125-2.

- ↑ Murashko, Alex (2012). "John Piper: God Gave Christianity a 'Masculine Feel'". Christian Post.

- ↑ Christine Thomasos (2012). "Tim Tebow Brings In a New Wave of Christian Athleticism". The Christian Post.

Tebow inspired a new term by ESPN, known as “muscular Christianity.” The QB showcases his faith by wearing bible verses on his face, tweeting scriptures and publicly admitting his love for Jesus Christ, while drawing fans’ attention on the football field.

- ↑ Mary Jane Dunlap (March 13, 2012). "KU professor researching Naismith, religion and basketball". Kansas University.

“Less well-known is that his game also was meant to help build Christian character and to inculcate certain values of the muscular Christian movement.” Although times have changed, Zogry sees analogies between the beliefs and activities of 19th-century sports figures such as James Naismith and Amos Alonzo Stagg, a Yale divinity student who pioneered football coaching, and those of 21st-century athletes such as Tim Tebow and Jeremy Lin.

External links

- Research Project on the YMCA, Amateur Sport in Asia, the Far Eastern Championship Games, and the Asian Games

- The Manly Christ: a New View". Robert Warren Conant. 1904.

- The Masculine Power of Christ; or, Christ Measured as a Man. Jason Noble Pierce. 1912.