Memento mori

Memento mori ("remember that you have to die")[2] is a Latin expression, originating from a practice common in Ancient Rome; as a general came back victorious from a battle, and during his parade ("Triumph") received compliments and honors from the crowd of citizens, he ran the risk of falling victim to haughtiness and delusions of grandeur; to avoid it, a slave stationed behind him would say "Respice post te. Hominem te memento" ( "Look after you [to the time after your death] and remember you're [only] a man."). It was then reused during the medieval period, it is also related to the ars moriendi ("The Art of Dying") and related literature. Memento mori has been an important part of ascetic disciplines as a means of perfecting the character by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and by turning the attention towards the immortality of the soul and the afterlife.[3]

In art, mementos mori are artistic or symbolic reminders of mortality.[2] In the European Christian art context, "the expression... developed with the growth of Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, and salvation of the soul in the afterlife."[4]

Pronunciation and translation

In English, the phrase is pronounced /məˈmɛnˌtoʊ ˈmɔːriː/, mə-MEN-toh MOR-ee.

Memento is the 2nd person singular future active imperative of meminī 'to remember, to bear in mind', usually serving as a warning: remember!; mori is the present active infinitive of morior, literally "to die".[5]

In other words, ‘remember death’ or ‘remember that you will die’.[6]

Historic usage

Classical

Plato's Phaedo, where the death of Socrates is recounted, introduces the idea that the proper practice of philosophy is "about nothing else but dying and being dead."[7] The Stoics were particularly prominent in their use of this discipline, and Seneca's letters are full of injunctions to meditate on death.[8]

Europe — Medieval through Victorian

The thought was then utilized in Christianity, whose strong emphasis on divine judgment, Heaven, Hell, and the Salvation of the soul brought death to the forefront of consciousness.[9] Many memento mori works are products of Christian art,[10] although there are equivalents in Buddhist art. In the Christian context, the memento mori acquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to the Nunc est bibendum (now is the time to drink) theme of Classical antiquity. To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one's thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife. A Biblical injunction often associated with the memento mori in this context is In omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua, et in aeternum non peccabis (the Vulgate's Latin rendering of Ecclesiasticus 7:40, "in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin.") This finds ritual expression in the rites of Ash Wednesday, when ashes are placed upon the worshipers' heads with the words, "Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust you shall return."

.jpg)

The most obvious places to look for memento mori meditations are in funeral art and architecture. Perhaps the most striking to contemporary minds is the transi, or cadaver tomb, a tomb that depicts the decayed corpse of the deceased. This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still create a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches. Later, Puritan tomb stones in the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, or angels snuffing out candles. These are among the numerous themes associated with skull imagery.

Another example of memento mori is provided by the chapels of bones, such as the Capela dos Ossos in Évora or the Capuchin Crypt in Rome. These are chapels where the walls are totally or partially covered by human remains, mostly bones. The entrance to the Capela dos Ossos has the sentence "We bones, lying here bare, await yours."

The famous danse macabre is another well-known example of the memento mori theme, with its dancing depiction of the Grim Reaper carrying off rich and poor alike. This and similar depictions of Death decorated many European churches. Danse Macabre, Op. 40, is a tone poem for orchestra written in 1874 by French composer Camille Saint-Saëns.

Timepieces were formerly an apt reminder that your time on Earth grows shorter with each passing minute. Public clocks would be decorated with mottos such as ultima forsan ("perhaps the last" [hour]) or vulnerant omnes, ultima necat ("they all wound, and the last kills"). Even today, clocks often carry the motto tempus fugit, "time flees". Old striking clocks often sported automata who would appear and strike the hour; some of the celebrated automaton clocks from Augsburg, Germany had Death striking the hour. The several computerized "death clocks" revive this old idea. Private people carried smaller reminders of their own mortality. Mary, Queen of Scots owned a large watch carved in the form of a silver skull, embellished with the lines of Horace.

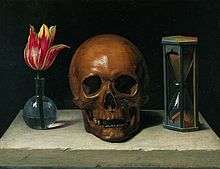

A version of the theme in the artistic genre of still life is more often referred to as a vanitas, Latin for "vanity". These include symbols of mortality, whether obvious ones such as skulls or more subtle ones such as a flower losing its petals. See the themes associated with the image of the skull.

After the invention of photography, many people had photographs taken of recently dead family members.

Memento mori was also an important literary theme. Well-known literary meditations on death in English prose include Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial and Jeremy Taylor's Holy Living and Holy Dying. These works were part of a Jacobean cult of melancholia that marked the end of the Elizabethan era. In the late eighteenth century, literary elegies were a common genre; Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Edward Young's Night Thoughts are typical members of the genre.

Apart from the genre of requiem and funeral music, there is also a rich tradition of memento mori in the Early Music of Europe. Especially those facing the ever-present death during the recurring bubonic plague pandemics from the 1340s onward tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable in chants, from the simple Geisslerlieder of the Flagellant movement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs. The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and god-given vale of tears with death as a ransom, and they reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance at Judgment Day. Two stanzas typical of memento mori in mediaeval music are from the virelai ad mortem festinamus of the Catalan Llibre Vermell de Montserrat from 1399:

- Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur,

- Mors venit velociter quae neminem veretur,

- Omnia mors perimit et nulli miseretur.

- Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.

- Life is short, and shortly it will end;

- Death comes quickly and respects no one,

- Death destroys everything and takes pity on no one.

- To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.

- Ni conversus fueris et sicut puer factus

- Et vitam mutaveris in meliores actus,

- Intrare non poteris regnum Dei beatus.

- Ad mortem festinamus peccare desistamus.

- If you do not turn back and become like a child,

- And change your life for the better,

- You will not be able to enter, blessed, the Kingdom of God.

- To death we are hastening, let us refrain from sinning.

In the late 16th and through the 17th century, memento mori rings were made.[11]

Religious use

Memento mori was the salutation used by the Hermits of St. Paul of France (1620-1633), also known as the Brothers of Death.[12] It is sometimes claimed that the Trappists use this salutation, but this is not true.[13]

Puritan America

Colonial American art saw a large number of memento mori images due to Puritan influence. The Puritan community in 17th-century North America looked down upon art because they believed that it drew the faithful away from God and, if away from God, then it could only lead to the devil. However, portraits were considered historical records and, as such, they were allowed. Thomas Smith, a 17th-century Puritan, fought in many naval battles and also painted. In his self-portrait, we see a typical puritan memento mori with a skull, suggesting his imminent death.

The poem under the skull emphasizes Thomas Smith's acceptance of death:

Why why should I the World be minding, Therein a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.

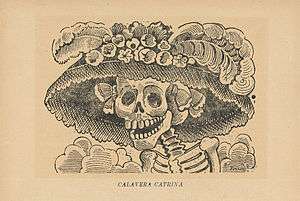

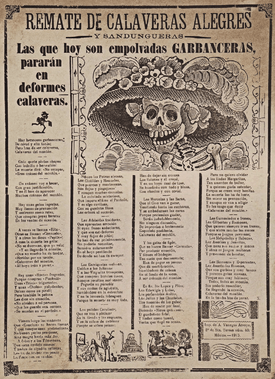

Mexico

Much memento mori art is associated with the Mexican festival Day of the Dead, including skull-shaped candies and bread loaves adorned with bread "bones."

This theme was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraver José Guadalupe Posada, in which various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

Another manifestation of memento mori is found in the Mexican "Calavera", a literary composition in verse form normally written in honour of a person who is still alive, but written as if that person were dead. These compositions have a comedic tone and are often offered from one friend to another during Day of the Dead.[14]

In Buddhism

Maraṇasati, a word occurring in the early Buddhist texts (the suttapiṭaka of the Pāli Canon (with parallels in the āgamas of the "Northern" Schools)), is a compound word in Pāli composed of the two words "maraṇa" and "sati". The translation of these words is similar (if not exactly the same) as the translation for "memento mori". Maraṇa means 'death' (and is most likely related to Latin 'mori' by way of a shared Proto-Indo-European root: "mer-") and sati can mean 'remember', so the compound word would mean something like "remember death" (memento mori).

Zen and Samurai

In Japan, the influence of Zen Buddhist contemplation of death on indigenous culture can be gauged by the following quotation from the classic treatise on samurai ethics, Hagakure:[15]

The Way of the Samurai is, morning after morning, the practice of death, considering whether it will be here or be there, imagining the most sightly way of dying, and putting one's mind firmly in death. Although this may be a most difficult thing, if one will do it, it can be done. There is nothing that one should suppose cannot be done.[16]

In the annual appreciation of cherry blossom and fall colours, Hanami and Momijigari, the Samurai philosophised that things are most splendid at the moment before their fall, and to aim to live and die in a similar fashion.

Tibetan Buddhism

In Tibetan Buddhism, there is a mind training practice known as Lojong. The second of the "preliminaries" to practice in this text is a call to "Be aware of the reality that life ends; death comes for everyone; Impermanence." This remembrance of the impermanence of life and the inevitability of death is one of the Four Thoughts, alternatively translated as Remembrances or Contemplations.

There is also the famous "Tibetan Book of the Dead" or Bardo Thodol and related literature.

In Islam

The "remembrance of death" ("dhikr al-mawt") has been a major topic of Islamic spirituality (i.e. "tazkiya" meaning self-purification, or purification of the heart) since the time of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina. It is grounded in the Qur'an, where there are recurring injunctions to pay heed to the fate of previous generations.[17] The hadith literature, which preserves the teachings of Prophet Muhammad, records advice for believers to "remember often death, the destroyer of pleasures."[18] Some Sufis have been called "ahl al-qubur," the "people of the graves," because of their practice of frequenting graveyards to ponder on mortality and the vanity of life, based on the teaching of the Prophet Muhammad to visit graves.[19] Al-Ghazali devotes to this topic the last book of his "Revival of the Religious Sciences".[20]

See also

- Carpe diem

- Et in Arcadia ego

- Post-mortem photography, sometimes called a memento mori

- Sic transit gloria mundi

- Ubi sunt

- You Only Live Once (disambiguation)

References

- ↑ Campbell, Lorne. Van der Weyden. London: Chaucer Press, 2004. 89. ISBN 1-904449-24-7

- 1 2 Literally 'remember (that you have) to die', Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, June 2001.

- ↑ See Jeremy Taylor, Holy Living and Holy Dying.

- ↑ "Final Farewell: The Culture of Death and the Afterlife". Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 2010-06-06. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ↑ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, ss.vv.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, s.v.

- ↑ Phaedo, 64a4.

- ↑ See his Moral Letters to Lucilius.

- ↑ Christian Dogmatics, Volume 2 (Carl E. Braaten, Robert W. Jenson), page 583

- ↑ Christian Art (Rowena Loverance), Harvard University Press, page 61

- ↑ Taylor, Gerald; Scarisbrick, Diana (1978). Finger Rings From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day. Ashmolean Museum. p. 76. ISBN 0-900090-54-5.

- ↑ F. McGahan, "Paulists", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Paulists

- ↑ E. Obrecht, "Trappists", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1912, s.v. Trappists

- ↑ Stanley Brandes. "Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond". Chapter 5: The Poetics of Death. John Wiley & Sons, 2009

- ↑ See a revised selection here.

- ↑ See "A Buddhist Guide to Death, Dying and Suffering".

- ↑ For instance, sura "Yasin", 36:31, "Have they not seen how many generations We destroyed before them, which indeed returned not unto them?".

- ↑ "Hadith - The Book of Miscellany - Riyad as-Salihin - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)".

- ↑ "Hadith - Book of Funerals (Kitab Al-Jana'iz) - Sunan Abi Dawud - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)".

- ↑ Al-Ghazali on Death and the Afterlife, tr. by T.J. Winter. Cambridge, Islamic Texts Society, 1989.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Memento mori. |

- Memento mori and vanitas elements in the funerary art at St. John's Co-Cathedral, Valletta, Malta, an article on memento mori and ars moriendi appearing in the journal Treasures of Malta, December 2004

- Memento Mori, an article appearing on the website of the Museum of Art and Archaeology

- Several articles on this topic at the Matheson Trust Library.

- Memento Mori - An example in ceramic art