Marshallese culture

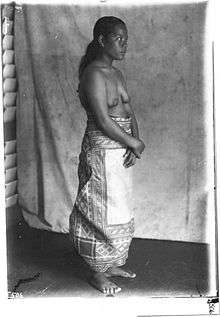

The Marshallese culture is marked by pre-Western contact and the impact of that contact on its people afterward. The Marshall Islands were relatively isolated. Inhabitants developed skilled navigators, able to navigate by the currents to other atolls. Prior to close contact with Westerners, children went naked and men and women were topless, wearing only skirts made of mats of native materials.

Land was and remains the most important measure of a family's wealth. Land is inherited through the maternal line.

Since the arrival of Christian missionaries, the culture has shifted from a subsistence-based economy towards a more traditional western economy and modesty standards have shifted to include women covering their bare thighs.

The people are friendly and peaceful. Strangers are received warmly. Consideration for others is important to the Marshallese people. Family and community are important. Concern for others is an outgrowth of their dependence on one another. They have lived for centuries on isolated coral atolls and islands. Relatives including grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins and far-flung relatives are all considered close family. The strong family ties contribute to close-knit communities rooted in the values of caring, kindness and respect.[1] One of the most significant family events is a child's first birthday.

The island culture was heavily impacted by the fight for Kwajalein Atoll during World War II and the United States nuclear testing program on Bikini Atoll from 1946 and 1958. Former residents and their descendants who were ousted after World War II receive compensation from the U.S. government. This dependence on aid has shifted residents' loyalty away from traditional chiefs. The island culture is heavily influenced today by the presence of about 2000 foreign personnel on the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site, which includes rocket launch, test, and support facilities on eleven islands of the Kwajalein Atoll, along with Wake Island and Aur Atoll.

Pre-western culture

The Marshallese were once skilled navigators, able to sail long distances aboard the two-hulled proa between the atolls using the stars and stick and shell charts.[2] They hold annual competitions sailing their proa, a ship made of teak panels tied together with rope made of palm and sealed with palm rope. The sail was anciently woven from palm fronds. The islanders were relatively isolated and had developed a well-integrated society bound by close extended family association and tradition.[2] Men and women wore only skirts made of native materials woven into mats. Children were generally naked.

Modern culture

The modern culture of the islanders is heavily influenced by Western Christian missionaries who began arriving in the late 19th century.[3] The economic activity of some Marshallese from the Bikini Islanders has been changed by their growing dependence on payments made by the U.S. government.

Clothing and dress

The men wore a fringe skirt of native materials about 25 to 30 inches (60 to 80 cm) long. Women traditionally[4] wore two mats about a yard (metre) square each, made by weaving pandanus and hibiscus leaves together,[2] and belted around the waist.[5] Children were usually naked.[2]

The missionaries influenced the islanders' notions of modesty. In 1919, a visitor reported that Marshall Islands women "are perfect models of prudery. Not one would think of exposing her ankles..." Every lagoon was led by a king and queen and a following of chieftains and chief women who comprised a ruling caste. Some of the leaders maintained Western-style bungalows and maintained servants, including secretaries, maids, and valets.

Poverty was non-existent. The islanders worked the copra plantations under the watchful eye of the Japanese, who took a portion of the sales. Chiefs could retain as much as US$20,000 per year. The remainder was distributed to the workers. The Marshall islanders were formerly aggressive, but the influence of the mission churches eliminated most conflict. They took pride in extending hospitality to one another, even distant relatives.[3]

Women in the Marshall Islands today are still very modest. They believe a woman's thighs[6] and shoulders should be covered.[7] Women generally wear cotton muʻumuʻus or similar clothing that covers most of the body. While personal health is never discussed except within the family, and although women are especially private about female-related health issues,[4] they are willing to talk about their breasts.[4]

Marshall island women swim in muʻumuʻus which are made of a fine polyester that quickly dries. In the capital of Majuro, revealing cocktail dresses are inappropriate for both islanders and guests.[7] With the increasing influence of Western media, the younger generation may wear shorts, though the older generation equates shorts with loose morals. T-shirts, jeans, skirts, and makeup are making their way via the media to the islands.[8]

Income

Before the advent of Western influence, the islanders' sustenance-based lifestyle was based on cultivating native plants and eating shellfish and fish. Payments made in the 20th century to descendants of Bikini Island residents as reparations for damage to the Bikini Atoll and the islanders' way of life have elevated their income relative to other Marshall Island residents. It has caused some Bikini islanders to become economically dependent on the payments from the trust fund. This dependency has eroded individual's interest in traditional economic pursuits like taro and copra production. The move also altered traditional patterns of social alliance and political organization. On Bikini, rights to land and land ownership were the major factor in social and political organization and leadership. After relocation and settlement on Kili, a dual system of land tenure evolved. Disbursements from the trust fund was based in part to land ownership on Bikini and based on current land tenure on Kili.[9]

Land-based wealth

The Marshallese society is matrilineal and land is passed down from generation to generation through the mother. Land ownership ties families together into clans. Grandparents, parents, grandchildren, aunts, uncles, and cousins form extended, close-knit family groups.[2] The islanders continue to maintain land rights as the primary measure of wealth.[10]

To all Marshallese, land is gold. If you were an owner of land, you would be held up as a very important figure in our society. Without land you would be viewed as a person of no consequence... But land here on Bikini is now poison land.[11]

Clan-based society

Marshallese social classes included distinct chiefs and commoners. The irooj laplap held the most power and were considered almost sacred or godly. To show respect, others stooped and approached on their knees. They always obeyed the orders of their high chief. The irooj laplap received the best food, could choose the best land, and had as many wives as they wanted. In return, they were responsible for leading the people in community work, on sailing expeditions, and in war. Their power was normally limited to one part or the whole of one atoll. A high chief who waged war successfully could conquer and control several atolls. The irooj laplap were followed by the irooj rik, the lesser chiefs, and finally the kajur, or commoner.[2]

Each family is part of a clan (Bwij), which owns all land. The clan owes allegiance to a chief (Iroij). The chiefs oversee the clan heads (Alap), who are supported by laborers (Rijerbal). The Iroij control land tenure, resource use and distribution, and settle disputes. The Alap supervise land maintenance and daily activities. The Rijerbal work the land including farming, cleaning, and construction.

The Marshallese society is matrilineal and land is passed down from generation to generation through the mother. Land ownership ties families together into clans, and grandparents, parents, grandchildren, aunts, uncles, and cousins form extended, close-knit family groups, and gatherings tend to become big events. One of the most significant family events is the first birthday of a child {kemem}, where relatives and friends celebrate with feasts and song.[2][12]

Before the residents were relocated, they were led by a local chief and under the nominal control of the Paramount Chief of the Marshall Islands. Afterward, they had greater interaction with representatives of the trust fund and the U.S. government and began to look to them for support.[9]

Language

English is the official language and is spoken widely, though not fluently. Most Marshallese speak both the Marshallese language аnd at least some English. Government agencies use Marshallese. Оne important word іn Marshallese іs "yokwe" whіch іs similar tо the Hawaiian "aloha" аnd means "hello", "goodbye" аnd "love".[13]

Legal

Unlike most other countries, the Marshall Islands have no copyright law.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ "Culture". Embassy of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Introduction to Marshallese Culture". Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- 1 2 McMahon, Thomas J. (November 1919). "The Land of the Model Husband". Travel. 34 (1).

- 1 2 3 Briand, Greta; Peters, Ruth (2010). "Community Perspectives on Cultural Considerations for Breast and Cervical Cancer Education among Marshallese Women in Orange County, California" (PDF). Californian Journal of Health Promotion (8): 84–89. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ Bliss, Edwin Munsell (1891). The Encyclopedia of Missions. II. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ↑ "Customs". Marshall Islands. FIU College of Business Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Marshall Islands". Encyclopedai.com. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ↑ "Republic of the Marshall Islands" (PDF). Culture Grams 2008. Ann Arbor, Michigan: ProQuest. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Bikini". Countries and their Cultures. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "Bikini History". Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Guyer, Ruth Levy (September 2001). "Radioactivity and Rights". American Journal of Public Health. 91 (9, issue 9): 1371–1376. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.9.1371. PMC 1446783

. PMID 11527760.

. PMID 11527760. - ↑ "Marshallese Culture". Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ↑ Destinations Marshall Islands

- ↑ Marshall Islands