Marathi people

| मराठी लोक | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| c. 74.7 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 71,936,894[2] | |

| 60,000[3][4] | |

| Languages | |

| Marathi and Marathi dialects | |

| Religion | |

|

Predominantly: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Aryan peoples | |

The Marathi people (Marathi: मराठी लोक) is an ethnic group of India that inhabits the Maharashtra region and as well as some border districts such as Belgaon and Karwar of Karnataka and Madgaon of Goa states in western India.[5] Their language, Marathi, is part of the southern group of Indo-Aryan languages. The group has been classified by British colonial era anthropologists as either Indo-Aryan or Scytho-Dravidian.[6][7] Although their history goes back more than two millennia, the community came to prominence when Maratha warriors under Shivaji Maharaj established the Maratha Empire in 1674. Marathi people are credited to a large extent for ending the Mughal rule in India.[8][9][10]

History

History from ancient to Medieval Period

During ancient period around 230 BC Maharashtra came under the rule of the Satavahana dynasty which ruled the region for 400 years.[11] The greatest ruler of the Satavahana Dynasty was Gautami putra Satakarni. The Vakataka dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the 3rd century to the 5th century.[12] The Chalukya dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the 6th century to the 8th century and the two prominent rulers were Pulakeshin II, who defeated the north Indian Emperor Harsh and Vikramaditya II, who defeated the Arab invaders in the 8th century. The Rashtra kuta Dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the 8th to the 10th century.[13] The Arab traveler Sulaiman called the ruler of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty (Amoghavarsha) as "one of the 4 great kings of the world".[14] From the early 11th century to the 12th century the Deccan Plateau was dominated by the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty.[15] The Seuna dynasty, also known as the Yadav dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the 13th century to the 14th century.[16] The Yadavas were defeated by the Khiljis in 1321.After the Yadav defeat, the area was ruled for the next 300 years by a succession of Muslim rulers including in the chronological order, the Khiljis , the Tughlaqs, the Bahamani Sultanate and its successor states such as Adilshahi and Nizamshahi and the Mughal Empire.[17]

Maratha Empire

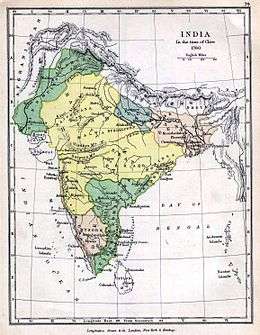

In the mid-17th century, Shivaji Maharaj (1630–1680) founded the Maratha Empire by conquering the Desh and the Konkan region from the Adilshahi , and re-establish Hindavi Swaraj("self-rule of Hindu people"[18]). The Marathas are credited to a large extent for ending the Mughal rule in India.[19][20][21][22] After Shivaji's death, the Mughals, who had lost significant ground to the Marathas under Shivaji, invaded Maharashtra in 1681. Shivaji's son Sambhaji and successor as Chhatrapati led the Marathas valiantly against the much stronger Mughal opponent but in 1689, after being betrayed, he was captured, and then tortured and killed by Mughal emperor, Aurangzeb.[23] The war against the Mughals was then led by the Sambhaji's younger brother and successor Rajaram Chhatrapati. Upon Rajaram's death in 1700, his widow Tarabai took command of Maratha forces and won many battles against the Mughals. In 1707, upon the death of Aurangzeb, the War of 27 years between the much weakened Mughals and Marathas came to an end.[24]

Shahu, the grandson of Shivaji, with the help of capable Maratha chieftains such as the Bhat Peshwas saw the greatest expansion of Maratha power.After Shahu's death in 1749, the Peshwa became the virtual rulers of the empire. The empire was expanded by many chieftains including Peshwa Bajirao Bhalar I and his descendants, the Shindes, Gaekwad, Pawar, Bhonsale of Nagpur and the Holkars. The empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu in the south, to Peshawar (modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa)[25] in the north, and Bengal in the east.[19][26] Pune under the Peshwa became the imperial seat with envoys, ambassadors and royals coming in from far and near. However, after the Third battle of Panipat in which the Marathas were defeated by Ahmed Shah Abdali, the Empire broke up into many independent kingdoms. Due to the efforts of Mahadji Shinde, it remained a confederacy until the British East India Company defeated Peshwa Bajirao II. Nevertheless, several Maratha states remained as vassals of the British until 1947 when they acceded to the Dominion of India.[27]

The Marathas also developed a potent Navy circa 1660s, which at its peak, dominated the territorial waters of the western coast of India from Mumbai to Savantwadi.[28] It would engage in attacking the British, Portuguese, Dutch, and Siddi Naval ships and kept a check on their naval ambitions. The Maratha Navy dominated till around the 1730s, was in a state of decline by 1770s, and ceased to exist by 1818.[29]

British colonial rule

Areas that correspond to present day Maharashtra were under direct or indirect British rule, first under the East India company and then under British crown from 1858. Marathi people during this era resided in the Bombay presidency, Berar, Central provinces, Hyderabad state and in various princely states that are currently part of the present day Maharashtra. Significant Marathi population also resided in Maratha princely states far from Maharashtra such as Baroda, Gwalior, Indore, and Tanjore.

British rule over more than a century saw huge changes that were seen in all spheres, social, economic and others as well.

Religion

The majority of Marathi people are Hindus.[30] Minorities by religion include Buddhists, Jains, Christians, Muslims and Jews.[30]

Castes and communities

Marathi people form an ethno-linguistic group that is distinct from others in terms of its language, history, cultural and religious practices, social structure, literature and art.[31]

Hindu castes

- Artisan castes. There are several artisan castes such as Lohar (Iron-smith), Aare kshatriya known as Arya kshatriya (Aare, Aare maratha) in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, Sutar (carpenters), Mali ( florists/vegetable farmers & gardener), Kumbhar (potters), Sonar (swarnakar / goldsmiths), Teli (oil pressers), and Nabhik (barbers). These communities fall under the Other Backward Class (OBC) classification. Other communities like the Bhavsars from the Nasik region along with Malis and Koshtis (weavers) from Maharashtra are economically more prosperous than their counterparts from other areas of India.

- Agri caste – Three major districts of Maharashtra namely Thane, Raigad and Mumbai are shelters of Agri Samaj. Salt making, fishery at the sea coast and farming of rice were the major occupations of this community.

- Bhandari – Traditional occupation was toddy tapping and as soldiers.[32]

- Brahmin – The five major sub-groups are Deshastha, Karhade, Kokanastha, Daivadnya and Saraswat.[33]

- Chambhar – Their traditional occupation was leather work. The community is designated as a Scheduled Caste

- (CKP) – Traditionally considered to be a well-educated Kshatriya-Brahmin community. They competed with Marathi Brahmins for military and administrative positions under Maratha and British rule. Socially and culturally, the community is close to the Marathi Brahmin community. They are also considered part of the broader Kayastha community.[34] The CKPs are today concentrated primarily in western Maharashtra, southern Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh (Indore region).[35]

- Bhoi - The 22 sub-groups of the community found there use the Ahirani language within their family and within kin groups but speak in Marathi while talking to the others

- Lonari - The lomesh Rushi belonged to this community.

- Dhangar – The Shepherd caste. The Holkar rulers of Indore belonged to this community. Today it is classified as a Nomadic Tribe by the Government of India

- Gurav – This community traditionally looked after Hindu temples and in some temples are the only temple priests.

- Mangela Koli – Society Of Mangela is Very Mature Caste in Koli. Is the Sub-Caste Of Koli.Is Belongs From Western Region Of Maharashtra.The etymology of the word Mangela comes from the words Mang, meaning fishing nets in the Marathi language and Ela meaning people. Literally, the word means a Fisherman, and the Mangela Koli are a community of Koli Fishermen.

- Matang – This community associate with the work of making ropes in villages. people from this community even serve as a village musicians. some of the squire doing farming in there land.

- Maratha – The Marathas were traditionally considered to be Kshatriya in the Hindu ritual ranking system known as varna.

- Kunbi – Kunbi people were the traditional peasant group in Maharashtra and are found all around Maharashtra and numerically form the largest group among Marathi people. For most of 20th century, the upper caste Maratha and the Kunbis were lumped together as one community. Now the Kunbis have been recognised as a separate OBC caste[note 1]

- Mahar – This community accounts for 10% of the population of Maharashtra.[36] Most of the Mahar community followed social reformer B. R. Ambedkar in converting to Buddhism in the mid 20th century and have been at the forefront of struggle for Dalit rights.[37][38] The community is designated as a Scheduled Caste

- Pathare Prabhu – A caste associated with Mumbai for centuries.

- Vanjari- A caste of farmers that is believed to have been migrated from Rajasthan centuries ago. Found in most of the maharashtra and mainly in marathwada.

- Ramoshi

- Wani – Marathi Trader caste

- Aare, Arya kshatriya - A caste of soldiers and agriculturist. The community is originally from Telgu speaking regions and moved to Maharashtra three hundred years ago.

Non-Hindu communities

- Buddhist - Most buddhist Marathi people belong to the former Mahar community who adopted Buddhism en masse with Dr. Ambedkar in 1956.

- Christians – Portuguese missionaries brought Catholicism to this area during the 15th century, giving rise to the East Indian Marathi community, who are concentrated in and around Mumbai. Protestantism was brought to the region by American and Anglican missionaries during the 19th century, resulting in the community of Marathi Christians who are found in many parts of Maharashtra but concentrated mainly in the districts of Ahmednagar and Solapur.

- Konkani Muslims are Marathi Muslims from the Konkan region who speak the Marathi language. Other Muslims in Maharashtra tend to identify with the Islamic culture of North India and mostly speak an Urdu dialect called Dakhni.

- Sikhs – There is a small Sikh community called Dakhani or Maharashtrian Sikhs who migrated from the Punjab and settled in Maharashtra around 300 years ago. They came to south with their tenth Guru, Govind Singh, who visited Nanded of Maharashtra in 1708. They are mostly concentrated in Nanded, Aurangabad, Nagpur and Mumbai. They are fluent in the Marathi language and only a few know Punjabi.[39]

- Jains – In present-day Maharashtra there many jain communities that are native to the area. The late educationalist Bhaurao Patil belonged to the Marathi jain community. The noted film personality of early Indian cinema, V. Shantaram's father was also a Marathi jain. Maharashtra had many Jain rulers such as the Rashtrakuta dynasty and the Shilaharas. Many of forts were built by kings from these dynasties and thus Jain temples or their remains are found in them. Texts such as the Shankardigvijaya and Shivlilamruta suggest that a large number of Maharashtrans were Jains in the ancient period.The first Marathi inscription known is at Shravanabelagola, Karnataka near the left foot of the statue of Bahubali, dated 981 CE.The oldest inscription in Maharashtra is a 2nd-century BC Jain inscription in a cave near Pale village in the Pune District. It was written in the Jain Prakrit and includes the Navkar Mantra.

- Jews – There is a community of Marathi Jews, popularly known as Bene Israel. It is estimated that there were 6,000 Bene Israel in the 1830s; 10,000 at the turn of the 20th century; and in 1948—their peak in India—they numbered 20,000. At present, they number around 60,000 in Israel,.[40][41] The number of Bene Israel remaining in India was estimated to be around 5,000 in 1988[42]

Marathi Diaspora

In other Indian states

As the Maratha Empire expanded across India, the Marathi population started migrating out of Maharashtra alongside their rulers. Peshwa, Holkars, Scindia and Gaekwad dynastic leaders took with them a considerable population of priests, clerks, clergymen, army men, businessmen and workers when they emigrated. These people have settled in various parts of India along with their rulers since the 1700s. Many families belonging to these groups still follow typical Marathi traditions even though they have lived more than 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from Maharashtra for more than 100 years.[43]

Other people have migrated in modern times in search of jobs outside Maharashtra. These people have also settled in almost all parts of the country. They have set up Maharashtra Mandals in many cities across the country. A national level central organization, the Brihan Maharashtra Mandal was formed in 1958[44] to promote Marathi culture outside Maharasthtra. Several sister organizations of the Brihan Maharashtra Mandal have also been formed outside India.[45]

Outside India

A group of Marathis also live in Nepal, where they have resided for around 17 generations

Notes:. However, they write their surnames differently and use Maharatta, Marahata, etc. The present-day Baloch tribes Bugtis and Marris are thought to be the descendants of Maratha soldiers and civilians who were taken as prisoners of war, after the defeat of Marathas in the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761[46]

In the 1800s, a large number of Indian people were taken to Mauritius, Fiji, South Africa, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, Jamaica, and other places in the Caribbean to as indentured laborers to work on sugarcane plantations. The majority of these migrants were from the Hindustani speaking areas or from Southern India, however, the migrants to Mauritius included a significant number of Marathis.[47][48]

Since the state of Israel was established in 1948, around 25,000-30,000 Jews have emigrated there, of which around 20,000 were from the Marathi speaking Bene Israel community.[49]

Indians including Marathi People have migrated to Europe and particularly Great Britain for more than a century. The Maharashtra Mandal of London was founded in 1932[50] A small number of Marathi people also settled in British East Africa during the colonial era.[51] After the African Great Lakes countries of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyka gained independence from Britain, most of the South Asian population residing there, including Marathi people, migrated to the United Kingdom,[52][53][54] or India.

Large-scale immigration of Indians into the United States started when the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 came into effect. Most of the Marathi immigrants who came after 1965 were professionals such as doctors, engineers or scientists. A second wave of immigration took place during the I.T. boom of the 1990s and later.

Mainly due to the I.T. boom and general ease of travel, Marathi people may be found in all corners of the world including Australia,[55] Canada,[56] Gulf countries,[57] European countries,[58] Japan and China.

Culture

Food

The many communities in Indo-Aryan Marathi society result in a diverse cuisine. This diversity extends to the family level because each family uses its own unique combination of spices. The majority of Maharashtrians do eat meat and eggs, but the Brahmin community is mostly lacto-vegetarian. The traditional staple food on Desh (the Deccan plateau) is usually bhakri, spiced cooked vegetables, dal and rice. Bhakri is an Unleavened bread made using Indian millet (jowar), bajra or bajri.[59] However, the North Maharashtrians and Urban people prefer roti, which is a plain bread made with Wheat flour.[60] In the coastal Konkan region, rice is the traditional staple food. An aromatic variety of ambemohar rice is more popular amongst Marathi people than the internationally known basmati rice. Malvani dishes use more wet coconut and coconut milk in their preparation. In the Vidarbha region, little coconut is used in daily preparations but dry coconut, along with peanuts, are used in dishes such as spicy savjis or mutton and chicken dishes.

Thalipeeth is a popular traditional breakfast flat bread bread that is prepared using bhajani, a mixture of many different varieties of roasted lentils.[61]

Marathi Hindu people observe fasting days when traditional staple food like rice and chapatis are avoided. However, milk products and non-native foods such as potatoes, peanuts and sabudana preparations (sabudana khicdi) are allowed, which result in a Carbohydrate rich alternative fasting cuisine.

Some Maharashtrian dishes including sev bhaji, misal pav and patodi are distinctly regional dishes within Maharashtra.

In metropolitan areas including Mumbai and Pune, the pace of life makes fast food very popular. The most popular forms of fast food amongst Marathi people in these areas are: bhaji, vada pav, misal pav and pav bhaji. More traditional dishes are sabudana khichdi, pohe, upma, sheera and panipuri. Most Marathi fast food and snacks are purely lacto-vegetarian in nature.[62][63]

In South Konkan, near Malvan, an independent exotic cuisine has developed called Malvani cuisine, which is predominantly non-vegetarian. Kombdi vade, fish preparations and baked preparations are more popular here. Kombdi Vade, a recipe from Konkan region. Deep fried flat bread made from spicy rice and urid flour served with chicken curry, more specifically with Malvani chicken curry..

Desserts are an important part of Marathi food and include puran poli, shrikhand, basundi, kheer, gulab jamun, and modak. Traditionally, these desserts were associated with a particular festival, for example, modaks are prepared during the Ganpati Festival.[64]

Attire

Traditionally, Marathi women commonly wore the sari, often distinctly designed according to local cultural customs.[65] Most middle aged and young women in urban Maharashtra dress in western outfits such as skirts and trousers or salwar kameez with the traditionally nauvari or nine-yard sari, disappearing from the markets due to a lack of demand.[66] Older women wear the five-yard sari. In urban areas, the five-yard sari is worn by younger women for special occasions such as marriages and religious ceremonies.[67] Among men, western dressing has greater acceptance. Men also wear traditional costumes such as the dhoti and pheta on cultural occasions. The Gandhi cap along with a long white shirt and loose pajama style trousers is the popular attire among older men in rural Maharathra.[65][68][69] Women wear traditional jewelleries derived from Marathas and Peshwas dynasties. Kolhapuri saaj, a special type of necklace, is also worn by Marathi women.[65] In urban areas, many women and men wear western attire.[69]

Hindu Festivals

Marathi Hindu people celebrate most of the all India Hindu festivals like Dasara, Diwali and Raksha Bandhan . These are, however, celebrated with certain Maharashtrian regional variations. Others festivals like Ganeshotsav have a more characteristic Marathi flavour.

The Marathi, Kannada and Telugu people follow the Deccan Shalivahana Hindu calendar, which may have subtle differences with calendars followed by other communities in India. The festivals described below are in a chronological order as they occur during a Shaka year, starting with Shaka new year festival of Gudhi Padwa,[70][71] .

Gudi Padwa

The first day of the month of Chaitra according to the Hindu Calendar, (usually in March) is celebrated as Marathi new year and also as the Kannada and Telugu new year known as Ugadi. A victory pole or Gudi is erected outside homes on the day. This day is considered one the three and half most auspicious days of the Hindu calendar and many new ventures and activities such as opening a new business etc. are started on this day. The leaves of Neem or and shrikhand are a part of the cuisine of the day.,[72][73][74]

Akshaya Tritiya

The third day of Vaishakh is celebrated as Akshaya Tritiya. This is one of the three and a half most auspicious days in the Hindu Calendar and usually occurs in the month of April. In Vidharbha region, this festival is celebrated in remembrance of the departed members of the family. The upper castes feed a brahmin and married couple on this day. The Mahars community used to celebrate it y offering food to crows.[75] This marks the end of the Haldi Kumkum festival which is a get-together organised by women for women. Married women invite lady friends, relatives and new acquaintances to meet in an atmosphere of merriment and fun. On such occasions, the hostess distributes bangles, sweets, small novelties, flowers, betel leaves and nuts as well as coconuts. The snacks include kairichi panhe (raw mango juice) and vatli dal, a dish prepared from crushed chickpeas.

Vat Savitri Pournima

This Vat Pournima festival is celebrated on Jyeshtha Purnima (full moon day of the Jyeshtha month in the Hindu calendar), around June. On this day, women fast and worship the banyan tree to pray for the growth and strength of their families, like the sprawling tree which lives for centuries. Married women visit a nearby tree and worship it by tying red threads of love around it. They pray for well-being and a long life for their husband.

Ashadhi Ekadashi

Ashadhi Ekadashi (11th day of the month of Ashadha, (falls in July– early August of Gregorian calendar) is closely associated with the Marathi sants Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram and others. Twenty days before this day, thousands of Varkaris start their pilgrimage to Pandharpur from the resting places of the saint. For example, in the case of Dynaneshwar, it starts from Alandi with Dynaneshwar's paduka (footwear made out of wood) in a Palakhi. Varkaris carry tals or small cymbals in their hand, wear a Hindu prayer beads made from tulasi around their necks and sing and dance to the devotional hymns and prayers to Vitthala. People all over Maharashtra fast on this day and offer prayers in the temples. This day marks the start of Chaturmas (The four monsoon months, from Ashadh to Kartik) according to the Hindu calendar. This is one of the most important fasting day for Marathi Hindu people.

Guru Purnima

The full moon day of the month of Ashadh is celebrated as Guru Purnima. For Hindus Guru-Shishya (teacher-student) tradition is very important, be it educational or spiritual. Gurus are often equated with God and always regarded as a link between the individual and the immortal. On this day spiritual aspirants and devotees worship Maharshi Vyasa, who is regarded as Guru of Gurus.

Divyanchi Amavasya

The new moon day/last day of the month of Ashadh/आषाढ (falls between June and July of Gregorian Calendar) is celebrated as Divyanchi Amavasya. This new moon signifies the end of the month of Ashadh, and the arrival of the month of Shravan, which is considered the most pious month of the Hindu calendar. On this day, all the traditional lamps of the house are cleaned and fresh wicks are put in. The lamps are then lit and worshiped. People cook a specific item called diva (literally lamp), prepared by steaming sweet wheat dough batter and shaping it like little lamps. They are eaten warm with ghee.

Nag Panchami

One of the many festivals in India during which Marathi people celebrate and worship nature. Nags (cobras) are worshiped on the fifth day of the month of Shravan (around August) in the Hindu calendar. On Nagpanchami Day, people draw a nag family depicting the male and female snake and their nine offspring or nagkul. The nag family is worshiped and a bowl of milk and wet chandan (sandalwood powder) offered. It is believed that the nag deity visits the household, enjoys languishing in the moist chandan, drinks the milk offering and blesses the household with good luck. Women put temporary henna tattoos (mehndi) on their hand on the previous day and buy new bangles on Nagpanchami Day. According to folklore, people refrain from digging the soil, cutting vegetables, frying and roasting on a hot plate on this day while farmers do not harrow their farms to prevent any accidental injury to snakes.

In a small village named Battis Shirala in Maharashtra a big snake festival is held which attracts thousands of tourists from all over the world. In other parts of Maharashtra, snake charmers are seen sitting by the roadsides or moving from one place to another with their baskets holding snakes. While playing the lingering melodious notes on their pungi, they beckon devotees with their calls – Nagoba-la dudh de Mayi (give milk to the cobra oh mother!). Women offer sweetened milk, popcorn (lahya in Marathi) made out of jwari/dhan/corns to the snakes and pray. Cash and old clothes are also given to the snake-charmers.

In Barshi Town in the Solapur district, a big jatra (carnival) is held at Nagoba Mandir in Tilak chowk.

Narali Purnima

Narali Purnima is celebrated on the full moon day of the month of Shravan in the Shaka Hindu calendar (around August). This is the most important festival for the coastal Konkan region because the new season for fishing starts on this day. Fishermen and women offer coconuts to the sea and ask for a peaceful season while praying for the sea to remain calm. The same day is celebrated as Rakhi Pournima to commemorate the abiding ties between brother and sister in Maharashtra as well other parts of Northern India. Narali bhaat (sweet rice with coconut) is the main dish on this day. On this day, Brahmin men change their sacred thread (Janve; Marathi: जानवे) at a common gathering ceremony called Shraavani (Marathi:श्रावणी).

Gokul Ashtami

The birthday of Krishna is celebrated with great fervour all over India on the 8th day of second fortnight of the month Shravan (usually in the month of August). In Maharashtra, Gokul Ashtami is synonymous with the ceremony of dahi handi. This is a reenactment of Krishna's efforts to steal butter from a matka (earthen pot) suspended from the ceiling. Large earthen pots filled with milk, curds, butter, honey, fruits etc. are suspended at a height of between 20 and 40 feet (6.1 and 12.2 m) in the streets. Teams of young men and boys come forward to claim this prize. They construct a human pyramid by standing on each other's shoulders until the pyramid is tall enough to enable the topmost person to reach the pot and claim the contents after breaking it. Currency notes are often tied to the rope by which the pot is suspended. The prize money is distributed among those who participate in the pyramid building. The dahi-handi draws huge crowd and they support the teams trying to grab these pots by chanting 'Govinda ala re ala'.

Mangala Gaur

Pahili Mangala Gaur (first Mangala Gaur) is one of the most important celebrations for the new brides amongst Marathi Brahmins. On the Tuesday of the month of the Shravan falling within a year after her marriage, the new bride performs Shivling puja for the well-being of her husband and new family. It is also a get-together of all women folk. It includes chatting, playing games, ukhane (married women take their husband's name woven in 2/4 rhyming liners) and sumptuous food. They typically play zimma, fugadi, bhendya (more popularly known as Antakshari in modern India) until the early hours of the following morning.

Bail pola/Pithori Amavasya

Pola or Bail Pola is celebrated on the new moon day (Pithori Amavasya) of the month of Shravan, which usually falls in August, to pay respect to bulls for their year-long hard work, as India is mostly an agricultural country. The festival is very important for farmers.

Hartalika

The third day of the month of Bhadrapada (usually around August/September) is celebrated as Hartalika in honour of Harita Gauri or the green and golden goddess of harvests and prosperity. A lavishly decorated form of Parvati, Gauri is venerated as the mother of Ganesha. Women fast on this day and worship Shiva and Parvati in the evening with green leaves. Women wear green bangles and green clothes and stay awake till midnight. Both married and unmarried women may observe this fast.

Ganeshotsav

This 11-day festival starts on Ganesh Chaturthi on the fourth day of Bhadrapada in honour of Ganesha, the God of wisdom. Hindu households install in their house, Ganesha idols made out of clay called shadu and painted in water colours. Early in the morning on this day, the clay idols of Ganesha are brought home while chanting Ganpati Bappa Morya and installed on decorated platforms.The idol is worshiped in the morning and evening with offerings of flowers, durva(strands of young grass), karanji and modaks.[76][77] The worship ends with the singing of an aarti in honour of Ganesha, other gods and saints. The worship includes singing the aarti "Sukhakarta Dukhaharta", composed by the 17th century saint, Samarth Ramdas .[78] Family traditions differ about when to end the celebration. Domestic celebrations end after 1 1⁄2, 3, 5, 7 or 11 days. At that time the idol is ceremoniously brought to a body of water (such as a lake, river or the sea) for immersion. In Maharashtra, Ganeshotsav also incorporates other festivals, namely Hartalika and the Gauri festival, the former is observed with a fast by women on the day before Ganesh Chaturthi whilst the latter by the installation of idols of Gauris.[79] In 1894, Nationalist leader Lokmanya Tilak turned this festival into a public event as means of uniting people towards the common goal of campaigning against British colonial rule. The public festival lasts for 11 days with various cultural programmes including music concerts, orchestra, plays and skits. Some social activities are also undertaken during this period like blood donation, scholarships for the needy or donation to people suffering from any kind of natural calamity.

Due to environmental concerns, a number of families now avoid bodies of water and let the clay statue disintegrate in a barrel of water at home. After a few days, the clay is spread in the home garden. In some cities a public, eco-friendly process is used for the immersion.[80]

Gauri / Mahalakshmi

Along with Ganesha, Gauri (also known as Mahalaxmi in the Vidharbha region of Maharashtra) festival is celebrated in Maharashtra. On the first day of the three-day festival, Gauris arrive home, the next day they eat lunch with a variety of sweets and on the third day they return to their home. Gauris arrive in a pair, one as Jyeshta (the Elder one) and another as Kanishta (the Younger one). They are treated with love since they represent the daughters arriving at their parents' home.

In many parts of Maharashtra including Marathwada and Vidarbha, this festival is called Mahalakshmi or Mahalakshmya or simply Lakshmya.

Anant Chaturdashi

The 11th day of the Ganesh festival (14th day of the month of Bhadrapada) is celebrated as Anant Chaturdashi, which marks the end of the celebration. People bid a tearful farewell to the God by immersing the installed idols from home / public places in water and chanting 'Ganapati Bappa Morya, pudhchya warshi Lawakar ya!!' (Ganesha, come early next year.) Some people also keep the traditional wow (Vrata) of Ananta Pooja. This invoves the worship of Ananta the coiled snake or Shesha on which Vishnu resides. A delicious mixture of 14 vegetables is prepared as naivedyam on this day.

Navratri and Ghatsthapana

Starting with first day of the month of Ashvin in the Hindu calendar (around the month of October), the nine-day and -night festival immediately preceding the most important festival Dasara is celebrated all over India with different traditions. In Maharashtra on the first day of this 10-day festival, idols of the Goddess Durga are installed at many homes. This installation of the Goddess is popularly known as Ghatsthapana. During this period, little girls celebrate 'Bhondla/Hadga' as the Sun moves to the thirteenth constellation of the zodiac called "Hasta" (Elephant). During the nine days, Bhondla (also known as 'Bhulabai' in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra) is celebrated in the garden or on the terrace during evening hours by inviting female friends of the daughter in the house. An elephant is drawn either with Rangoli on the soil or with a chalk on a slate and kept in the middle. The girls go around it in a circle, holding each other's hands and singing Bhondla songs. All Bhondla songs are traditional songs passed down through the generations. The last song typically ends with the words '...khirapatila kaay ga?' ('What is the special dish today?'). This 'Khirapat' is a special dish or dishes often made laboriously by the mother of the host girl. The food is served only after the rest of the girls have guessed what the covered dish or dishes are correctly.

There are some variations about how the Navratri festival is celebrated. For example, in many Brahmin families, celebrations include offering lunch for nine days to specially invited group of guests. The guests include a Married Woman (Marathi:सवाष्ण ), a Brahmin and, a Virgin (Marathi:कुमारिका). In the morning and evening, the head of the family ritually worships to either the goddess Durga, Lakshmi or Saraswati. On the eighth day, a special rite is carried out in some families. A statue of goddess Mahalakshmi with the face of a rice mask, is prepared and worshiped by newly married girls. In the evening of that day, women blow into earthen or metallic pots as a form of worship to please the goddess. Everyone in the family accompanies them by chanting verses and Bhajans. The nine day festival ends with a Yagna or reading of a Hindu Holy book (Marathi:पारायण ). [43]

Dasara

This Dasara festival is celebrated on the tenth day of the Ashvin month (around October) according to the Hindu Calendar. This is one of the three and a half most auspicious days in the Hindu Lunar calendar, when every moment is important. On the last day (Dasara day), the idols installed on the first day of the Navratri are immersed in water. This day also marks the victory of Rama over Ravana. People visit each other and exchange sweets. On this day, people worship the Aapta tree and exchange its leaves (known as golden leaves) and wish each other future like gold. There is a legend involving Raghuraja, an ancestor of Rama, the Aapta tree and Kuber. There is also another legend about the Shami tree where the Pandava hid their weapons during their exile.

Kojagari

Written in the short form of Sanskrit as 'Ko Jagarti (को जागरति) ?' ( Sandhi of "कः जागरति," meaning 'Who is awake?'), Kojagiri is celebrated on the full moon day of the month of Ashwin. It is said that on this Kojagiri night, the Goddess Lakshmi visits every house asking "Ko Jagarti?" and blesses those who are awake with fortune and prosperity. To welcome the Goddess, houses, temples, streets, etc. are illuminated. People get together on this night usually in open spaces (e.g. in gardens or on terraces) and play games until midnight. At that hour, after seeing the reflection of the full moon in milk boiled with saffron and various varieties of dry fruits, they drink the concoction. The eldest child in the household is honoured on this day.

Diwali

Just like most other parts of India, Diwali is one of the most popular Hindu festivals. Houses are illuminated for the festival with rows of clay lamps and decorated with rangoli and aakash kandils (decorative lanterns of different shapes and sizes). Diwali is celebrated with new clothes, firecrackers and a variety of sweets in the company of family and friends. In Maharashtrian tradition, during days of Diwali, family members have a ritual bath before dawn and then sit down for a breakfast of fried sweets and savory snacks. These sweets and snacks are offered to visitors to the house during the multi-day festival and exchanged with neighbors. Typical sweet preparations include Ladu, Anarse, Shankarpali and Karanjya. Popular savory treats include chakli, shev and chiwda.[81] Being high in fat and low in moisture, these snacks can be stored at room temperature for many weeks without spoiling.

Kartiki Ekadashi and Tulsi Vivah

The 11th day of the month of Kartik marks the end of Chaturmas and is called Kartiki Ekadashi (also known as Prabodhini Ekadashi). On this day, Hindus, particularly the followers of Vishnu, celebrate his awakening after a Yoganidra of four months of Chaturmas. People worship him and fast for the entire day.

The same evening or the evening of the next day is marked by Tulsi Vivah (Tulshicha Lagna). The Tulsi (Holy Basil plant) is held sacred by the Hindus as it is regarded as an incarnation of Mahalaxmi who was born as Vrinda. The end of Diwali celebrations marks the beginning of Tulsi-Vivah. Maharashtrians organise the marriage of a sacred Tulsi plant in their house with Krishna. On this day the Tulsi vrindavan is coloured and decorated as a bride. Sugarcane and branches of tamarind and amla trees are planted along with the tulsi plant. Though a mock marriage, all the ceremonies of an actual Maharashtrian marriage are conducted including chanting of mantras, Mangal Ashtaka and tying of Mangal Sutra to the Tulsi. Families and friends gather for this marriage ceremony which usually takes place in the late evening. Various poha dishes are offered to Krishna and then distributed among family members and friends. This also marks the beginning of marriage season. The celebration lasts for three days and ends on Kartiki Poornima or Tripurari Poornima.

Khandoba Festival/Champa Shashthi

Champa Shashthi, a six-day festival, from the first to sixth lunar day of the bright fortnight of the Hindu month of Margashirsha, is celebrated in honour of Khandoba by many Marathi families. Ghatasthapana, similar to navaratri, also takes place in households during this festival. A number of families also hold fasts during this period. The fast ends on the sixth day of the festival called Champa Shashthi.[82] Among some Marathi Hindu communities, the Chaturmas period ends on Champa Sashthi. As it is customary in these communities not to consume onions, garlic and egg plant (Brinjal / Aubergine) during the Chaturmas, the consumption of these food items resumes with ritual preparation of Bharit (Baingan Bharta) and rodga, small round flat breads prepared from jwari (white millet).

Bhogi

The eve of the Hindu festival 'Makar Sankranti' and the day before is called Bhogi. Bhogi is a festival of happiness and enjoyment and generally takes place on 13 January. It is celebrated in honour of Indra, "the God of Clouds and Rains". Indra is worshiped for the abundance of the harvest, which brings plenty and prosperity to the land. Since it is held in the winter, the main food for Bhogi is mixed vegetable curry made with carrots, lima beans, green capsicums, drumsticks, green beans and peas. Bajra roti (i.e. roti made of Pearl millet) topped with sesame as well as rice and mung dal khichadi are eaten to keep warm in winter. During this festival people also take baths with sesame seeds.

Makar Sankranti

Sankraman means the passing of the sun from one zodiac sign to the next. This day marks the sun's passage from the Tropic of Dhanu (Sagittarius) to Makar (Capricorn). Makar Sankranti falls on 14 January in non-leap years and on 15 January in leap years. It is the only Hindu festival that is based on the solar calendar rather than the Lunar calendar. Maharashtrians exchange tilgul or sweets made of jaggery and sesame seeds along with the customary salutation, Tilgul ghya aani god bola, which means "Accept the Tilgul and be friendly. Tilgul Poli or gulpoli are the main sweet preparations made on the day in Maharashtra. It is a wheat-based flat bread filled with sesame seeds and jaggery.,[83][84]

Maha Shivratri

Maha Shivratri (also known as Maha Sivaratri, Shivaratri or Sivarathri) means Great Night of Shiva or Night of Shiva. It is a Hindu festival celebrated every year on the 13th night and 14th day of Krishna Paksha (waning moon) of the month of Maagha (as per Shalivahana or Gujarati Vikrama) or Phalguna (as per Vikrama) in the Hindu Calendar, that is, the night before and day of the new moon. The festival is principally celebrated by offerings of bael (bilva) leaves to Shiva, all day fasting and an all night long vigil. Per The fasting food on this day includes chutney prepared with pulp of the kavath fruit (Limonia).[85]

Holi

The festival of Holi falls in Falgun, the last month of the Marathi Shaka calendar. Marathi people celebrate this festival by lighting a bonfire and offering puran poli to the fire. In North India, Holi is celebrated over two days with the second day celebrated with throwing colours. In Maharashtra it is known as Dhuli Vandan. However, Maharashtrians celebrate color throwing five days after Holi on Rangpanchami. In Maharashtra, people make puran poli as the ritual offering to the holy fire.[86]

Village Urus or Jatra

A large number of villages in Maharashtra hold their annual festivals (village carnivals) or urus in the months of January–May. These may be in the honour of the village Hindu deity (Gram devta) or the tomb (dargah) of a local Sufi Pir saint. Apart from religious observations, celebrations may include bullock-cart racing, kabbadi, wrestling tournaments, a fair and entertainment such as a lavani/tamasha show by travelling dance troupes.[87][88][89] A number of families eat meat preparations only during this period. In some villages, women are given a break from cooking and other household chores by their men folk.[90]

Festivals observed by Other Communities

Dhamma Chakra Pravartan Din

On 14 October 1956 at Nagpur, Maharashtra, India, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar embraced Buddhist religion publicly and gave Deeksha of Buddhist religion to his more than 380,000 followers.[91] This is believed to be the conversion by the largest number of people at a single event in the history of the world. The day is celebrated as Dharmacakra Pravartan Din. The grounds in Nagpur on which the conversion ceremony took place is known as Deekshabhoomi. Every year more than million Buddhist people especially Ambedkarite from all over the world visit Deekshabhoomi to commemorate Dhamma Chakra Pravartan Din.[92]

Christmas or Naataal (Marathi:नाताळ)

Christmas is celebrated to mark the birthday of Jesus Christ. Like in other parts of India, Christmas is celebrated with zeal by a large number of Marathi people, both Christians and non-Christians. Owing to the Portuguese influence on Maharashtra, Christmas is also known as 'Naataal', a word similar to 'Natal' used in Portuguese.

Literature

Ancient Marathi Inscriptions

Marathi, also known as Suena at that time, was the court language during the reign of the Yadava Kings. Yadava king Singhania was known for his magnanimous donations. Inscriptions recording these donations are found written in Marathion on stone slabs in the temple at Kolhapur in Maharashtra. Composition of noted works of scholars like Hemadri are also found. Hemadri was also responsible for introducing a style of architecture called Hemandpanth. Among the various stone inscriptions are those found at Akshi in the Kolaba district, which are the first known stone inscription in Marathi.An example found at the bottom of the statue of Gomateshwar (Bahubali) at Shravanabelagola in Karnataka bears the inscription "Chamundraye karaviyale, Gangaraye suttale karaviyale" which gives some information regarding the sculptor of the statue and the king who ordered its construction.

Classical Literature

Marathi people have a long literary tradition which started in the ancient era. However, it was the 13th-century saint, Jñāneśvar who made writing in Marathi popular among the masses. His Dnyaneshwari is considered a masterpiece. Along with Jñāneśvar, Namdev was also responsible for propagating Marathi religious Bhakti literature . Namdev is also important to the Sikh tradition, since several of his compositions are enshrined in the Guru Granth Sahib. Eknath,[93] Sant Tukaram,[94] Mukteshwar and Samarth Ramdas were equally important figures in the 17th century. In the 18th century, writers like Vaman Pandit, Raghunath Pandit, Shridhar Pandit, Mahipati and Mororpanta produced some well-known works. All of the above-mentioned writers produced religious literature.

Modern Marathi Literature

The first English book was translated into Marathi in 1817 while the first Marathi newspaper started in 1841.[95] Many books on social reform were written by Baba Padamji (Yamuna Paryatana, 1857), Mahatma Jyotiba Phule, Lokhitawadi, Justice Mahadev Govind Ranade, Hari Narayan Apte (1864–1919) etc. Lokmanya Tilak's newspaper Kesari, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar's newspaper Bahishkrut Bharat set up in 1927, provided a platform for sharing literary views. Marathi at this time was efficiently aided by Marathi Drama.

In the mid-1950s, the "little magazine movement" gained momentum. It published writings which were non-conformist, radical and experimental. The Dalit literary movement also gained strength due to the little magazine movement. This radical movement was influenced by the philosophy of and challenged the literary establishment, which was largely middle class, urban and upper caste. The little magazine movement threw up many excellent writers including the well-known novelist, critic and poet Bhalchandra Nemade. Dalit writer N. D. Mahanor is well known for his work while Dr. Sharad Rane is a well-known Children's writer.[96]

Martial tradition

Although ethnic Marathis have taken up military roles for many centuries,[97] their martial qualities came to prominence in seventeenth century India, under the leadership of the legendary emperor Chhatrapati Shivaji. Shivaji carved out his independent Hindu kingdom known as the Maratha Empire, which at some point controlled practically the entire Indian subcontinent, extending over large and distant areas of the country.[98][99] It was largely an ethnic Marathi polity,[100] with its chiefs and nobles coming from the Marathi ethnicity, such as the Chhatrapatis (Maratha caste), Maharaja Holkars (Dhangar caste),[101] Peshwas (1713 onwards)(Chitpavan caste),[102] Angres, chief of Maratha Navy (Koli caste)(1698 onwards).[103] The Marathas are credited to a large extent for ending the Mughal rule in India.[104][105] Further, they were also considered by the British as the most important native power of 18th century India.[106][107] Today this ethnicity is represented in the Indian Army, with two regiments deriving their names from Marathi communities —the Maratha Light Infantry[108] and the Mahar Regiment.[109]

See also

- List of Maratha dynasties and states

- List of Marathi people

- Thanjavur Marathi (disambiguation)

- Western Satraps

- Maratha Empire

Footnotes

- ↑ There are numerous castes in India categorized as OBC. The Indian government offers many affirmative action schemes for the upliftment of poor OBC by reserving a percentage of public sector jobs and places for students in Government run institutions of Higher learning.

References

- ↑ "Marathi population figure worldwide". Ethnologue. August 2008.

- ↑ "Census of India". Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ Weil, S. (2012). "The Bene Israel Indian Jewish family in Transnational Context." Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 71–80.

- ↑ Shalva Weil, Journal of Comparative Family Studies Vol. 43, No. 1, "The Indian Family: A Revisit" (January–February 2012), pp. 71-80,

- ↑ "Marathi People- People of Maharashtra- About Maharashtrians".

- ↑ Barnett, Lionel D. Antiquities of India: An Account of the History and Culture of Ancient Hindustan. p. 31.

- ↑ Wright, Arnold. Southern India: Its History, People, Commerce, and Industrial Resources. p. 71.

- ↑ Pearson, M. N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi:10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Delhi, the Capital of India".

- ↑ An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen p.Introduction-14. The author says: "The victory at Bhopal in 1738 established Maratha dominance at the Mughal court"

- ↑ India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic: p.440

- ↑ History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. by Sigfried J. de Laet,Joachim Herrmann p.392

- ↑ Indian History - page B-57

- ↑ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set): p.203

- ↑ The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 by Romila Thapar: p.365-366

- ↑ People of India: Maharashtra, Part 1 by B. V. Bhanu p.6

- ↑ "Kingdoms of South Asia – Indian Bahamani Sultanate". The History Files, United Kingdom. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ↑ Jackson, William Joseph (2005). Vijayanagara voices: exploring South Indian history and Hindu literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 38. ISBN 9780754639503.

- 1 2 Pearson, M. N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi:10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Delhi, the Capital of India".

- ↑ An Advanced History of Modern India By Sailendra Nath Sen p.Introduction-14. The author says: "The victory at Bhopal in 1738 established Maratha dominance at the Mughal court"

- ↑ "Is the Pakistan army martial?". The Express Tribune. 29 September 2012.

- ↑ Sambhaji – Patil, Vishwas, Mehta Publishing House, Pune, 2006

- ↑ Maharani Tarabai of Kolhapur, c. 1675–1761 A.D.

- ↑ "An Advanced History of Modern India".

- ↑ Andaman & Nicobar Origin | Andaman & Nicobar Island History. Andamanonline.in.

- ↑ "Full text of "Selections from the papers of Lord Metcalfe; late governor-general of India, governor of Jamaica, and governor-general of Canada"". archive.org.

- ↑ Sridharan, K. Sea: Our Saviour. New Age International (P) Ltd. ISBN 81-224-1245-9.

- ↑ Sharma, Yogesh. Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India. Primus Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-93-80607-00-9.

- 1 2 "Maharashtra Religions".

- ↑ Changing India: Bourgeois Revolution on the Subcontinent by Robert W. Stern, p. 20

- ↑ -Pereira, Andrew (Feb 12, 2012). "Treasurers of yore, now key to political fortune". The Times of India. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ↑ Shrivastav, P.N. (1971). Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers: Hoshangabad. Bhopal, India: Madhya Pradesh District Gazetteers. pp. 138–139. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ↑ D. Shyam Babu; Ravindra S. Khare (2011). Caste in Life: Experiencing Inequalities. Pearson Education India. p. 165. ISBN 978-81-317-5439-9. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ Susan Bayly (22 February 2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ Fred Clothey (26 February 2007). Religion in India: A Historical Introduction. Psychology Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-415-94023-8.

- ↑ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). "The 'Solution' of Conversion". Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. Orient Blackswan Publisher. pp. 119–131. ISBN 8178241560.

- ↑ Zelliott, Eleanor (1978). "Religion and Legitimation in the Mahar Movement". In Smith, Bardwell L. Religion and the Legitimation of Power in South Asia. Leiden: Brill. pp. 88–90. ISBN 9004056742.

- ↑ People of India: Maharashtra, Volume 1 By Kumar Suresh Singh, B. V. Bhanu, Anthropological Survey of India, p 463

- ↑ Weil, S. (2012). "The Bene Israel Indian Jewish family in Transnational Context." Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 71–80.

- ↑ Shalva Weil, Journal of Comparative Family Studies Vol. 43, No. 1, "The Indian Family: A Revisit" (January–February 2012), pp. 71-80, https://www.academia.edu/3524659/The_Bene_Israel_Indian_Jewish_Family_in_Transnational_Context

- ↑ Katz, N., & Goldberg, E. (1988). "The Last Jews in India and Burma." Jerusalem Letter, 101.

- 1 2 Gangadhar Ramchandra Pathak, ed. (1978). Gokhale Kulavruttant गोखले कुलवृत्तान्त (in Marathi) (2nd ed.). Pune, India: Sadashiv Shankar Gokhale. pp. 120, 137.

- ↑ Synques. "Brihan Maharashtra Mandal".

- ↑ "Bruhan Maharashtra Mandal of North America - Promote and nurture Marathi culture".

- ↑ Kay Benedict (27 November 2005). "Meeting after 244 years". DNA India.

- ↑ People.http://www.mauritiusmarathi.org/menu/history.php

- ↑ Archived 10 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://indiandiaspora.nic.in/diasporapdf/chapter9.pdf

- ↑ Archived 19 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Pathak, A.R., 1995. Maharastrian Immigrants in East Africa and Their Leisure. World Leisure & Recreation, 37(3), pp.31-32.

- ↑ Quest for equality (New Delhi, 1993), p. 99

- ↑ Donald Rothchild, `Citizenship and national integration: the non-African crisis in Kenya', in Studies in race and nations (Center on International Race Relations, University of Denver working papers), 1}3 (1969±70), p. 1

- ↑ "1972: Asians given 90 days to leave Uganda". British Broadcasting Corporation. 7 August 1972. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ↑ "Marathi Sydney, MASI, Maharastrians in Sydney, Marathi Mandal « Marathi Association Sydney Inc (MASI)". Marathi.org.au. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ↑ "Marathi Bhashik Mandal Toronto, Inc". Mbmtoronto.com. 2008-11-15. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ↑ "三菱の車 » Blog Archive » 人気のトラック".

- ↑ 人気ファンデーションで綺麗に魅せる. "人気ファンデーションで綺麗に魅せる". Ems2008.org. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ↑ Khatau, Asha (2004). Epicure S Vegetarian CuisinesJOf India. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan ltd. p. 57. ISBN 81-7991-119-5.

- ↑ Reejhsinghani, Aroona (2007). Delights From Maharashtra (7th ed.). Jaico;. ISBN 978-8172245184. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ↑ Epicure S Vegetarian Cuisines Of India. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan ltd. p. 63.

- ↑ ""Vada pav sandwich recipe"". Guardian News and Media Limited.

- ↑ ""In search of Mumbai Vada Pav"". The Hindu.

- ↑ "SAVOUR MUMBAI: A CULINARY JOURNEY THROUGH INDIA'S MELTING POT".

- 1 2 3 "Costumes of Maharashtra". Maharashtra Tourism. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ Kher 2003.

- ↑ Kher, Swati (2003). "Bid farewell to her". Indian Express, Mumbai Newsline. Archived from the original on 1 March 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ Bhanu, B.V (2004). People of India: Maharashtra, Part 2. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. pp. 1033, 1037, 1039. ISBN 81-7991-101-2.

- 1 2 "Traditional costumes of Maharashtra". Marathi Heritage Organization. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ Betham, R.M., 1908. Marathas and Dekhani Musalmans. Asian Educational Services.

- ↑ Lall, R. Manohar. Among the Hindus: A Study of Hindu Festivals. Asian Educational Services, 1933.

- ↑ Express News Service 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Ahmadnagar District Gazeteers 1976a.

- ↑ Lall, R. Manohar (2004). Among the Hindus : a study of Hindu festivals. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-8120618220. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ Lall, R. Manohar (2004). Among the Hindus : a study of Hindu festivals. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 79–91. ISBN 978-8120618220. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ "What is the significance of 'durva' in Ganesh Poojan ?". http://www.sanatan.org/. Retrieved 3 January 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Sharma, Usha (2008). Festivals In Indian Society (2 Vols. Set). New Delhi: Mittal publications. p. 144. ISBN 81-8324-113-1.

- ↑ Shanbag, Arun (2007). Prarthana: A Book of Hindu Psalms. Arlington, MA: Arun Shanbag. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-9790081-0-8.

- ↑ Pattanaik, Devdutt (2011). 99 thoughts on Ganesha : [stories, symbols and rituals of India's beloved elephant-headed deity]. Mumbai: Jaico Pub House. p. 61. ISBN 978-81-8495-152-3. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Zha, Bagish K. (20 September 2013). "Eco-friendly 'Ganesh Visarjan' save water and soil from getting polluted in Indore". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ Edmund W. Lusas; Lloyd W. Rooney (5 June 2001). Snack Foods Processing. CRC Press. pp. 488–. ISBN 978-1-4200-1254-5.

- ↑ [A HISTORY OF THE MARATHA PEOPLE , C A. KINCAID, CV.O., I.CS. AND Rao Bahadur D. B. PARASNIS, VOL II , page 314, HUMPHREY MILFORD, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS, 1922]

- ↑ Naik*, S.N.; Prakash, Karnika (2014). "Bioactive Constituents as a Potential Agent in Sesame for Functional and Nutritional Application". JOURNAL OF BIORESOURCE ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY. 2 (4): 42–60.

- ↑ Sen, Colleen Taylor (2004). Food culture in India. Westport, Conn.[u.a.]: Greenwood. p. 142. ISBN 978-0313324871. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Deshmukh, B. S.; Waghmode, Ahilya (July 2011). "Role of wild edible fruits as a food resource: Traditional knowledge" (PDF). INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES. 2 (7): 919–924.

- ↑ Taylor Sen, Colleen (2014). Feasts and Fasts A History of Indian Food. London: Reaktion Books. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-78023-352-9. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ↑ Shodhganga. "Sangli District" (PDF). Shodhganga. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ "Maharashtra asks high court to reconsider ban on bullock cart races". Times of india. Oct 19, 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ TALEGAON DASHASAR - The Gazetteers Department. The Gazetteers Department, Maharashtra.

- ↑ Betham, R. M. (1908). Maráthas and Dekhani Musalmáns. Calcutta. p. 71. ISBN 81-206-1204-3.

- ↑ This was Ambedkar's own figure given by him in a letter to Devapriya Valishinha dated 30 October 1956. The Maha Bodhi Vol. 65, p.226, quoted in Dr. Ambedkar and Buddhism by Sangharakshita.

- ↑ "Places to Visit". District Collector Office, Nagpur Official Website.

- ↑ "Sant Eknath Maharaj". Santeknath.org. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ↑ http://www.sankeertanam.com/saints%20texts/Sant%20TukArAm.pdf

- ↑ "Printing India". Printing India. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ↑ Nagarkar, Kiran (2006). The Language Conflicts: The Politics and Hostilities between English and the Regional Languages in India (PDF).

- ↑ James B. Minahan (30 August 2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-59884-660-7. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ↑ Career's Indian History. Bright Publications. p. 141.

- ↑ Ansar Hussain Khan; Ansar Hussain (1 January 1999). Rediscovery of India, The: A New Subcontinent. Orient Blackswan. p. 133. ISBN 978-81-250-1595-6.

- ↑ "Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia".

- ↑ "Caste, Conflict and Ideology".

- ↑ "Citpavan - Indian caste". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Bakshi, SR. Contemporary Political Leadership in India. APH Publishing Corporation. p. 41.

- ↑ "The Marathas". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ "Bal Gangadhar Tilak". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ A History of Modern India, 1480-1950.

- ↑ Justice System and Mutinies in British India.

- ↑ "Land Forces Site - The Maratha Light Infantry". Bharat Rakshak. 2003-01-30. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ↑ "Land Forces Site - The Mahar Regiment". Bharat Rakshak. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

External links

| Look up Maharashtrian in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marathi people. |