List of patent claim types

| Patent law |

|---|

| Overviews |

| Basic concepts |

| Patentability |

| Additional requirements |

| By region / country |

| By specific subject matter |

| See also |

|

This is a list of special types of claims that may be found in a patent or patent application. For explanations about independent and dependent claims and about the different categories of claims, i.e. product or apparatus claims (claims referring to a physical entity), and process, method or use claims (claims referring to an activity), see Claim (patent), section "Basic types and categories".

Beauregard

In United States patent law, a Beauregard claim is a claim to a computer program written in the form of a claim to an article of manufacture: a computer-readable medium on which are encoded, typically, instructions for carrying out a process. This type of claim is named after the decision In re Beauregard.[1] The computer-readable medium that these claims contemplate is typically a floppy disk or CD-ROM, which is why this type of claim is sometimes called a "floppy disk" claim.[2] In the past claims to pure instructions were generally considered not patentable because they were viewed as "printed matter," that is, like a set of instructions written down on paper. However, in In re Beauregard the Federal Circuit vacated for reconsideration in the PTO the patent-eligibility of a claim to a computer program encoded in a floppy disk, regarded as an article of manufacture.[Notes 1] Consequently, such computer-readable media claims are commonly referred to as Beauregard claims.

When first used in the mid-1990s, Beauregard claims held an uncertain status, as long-standing doctrine held that media that contained merely "non-functional" data (i.e., data that did not interact with the substrate on which it was printed) could not be patented. This was the "printed matter" doctrine which ruled that no "invention" that primarily constituted printed words on a page or other information, as such, could be patented. The case from which this claim style derives its name, In re Beauregard (1995), involved a dispute between a patent applicant who claimed an invention in this fashion, and the PTO, which rejected it under this rationale. The appellate court (the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit) accepted the applicant's appeal - but chose to remand for reconsideration (rather than affirmatively ruling on it) when the Commissioner of Patents essentially conceded and abandoned the agency's earlier position. Thus, the courts have not expressly ruled on the acceptability of the Beauregard claim style, but its legal status was for a time accepted.[3]

However, although time has rendered the issue essentially moot with regard to conventional media, such claims were originally and perhaps still can be more widely applied.[4] The particular inventions to which Beauregard-style claims were originally directed—i.e., programs encoded on tangible computer-readable media (CD-ROMs, DVD-ROMs, etc.)—are no longer as important commercially, because software deployment is rapidly shifting from tangible computer-readable media to network-transfer distribution (Internet delivery). Thus, Beauregard-style claims are now less commonly drafted and prosecuted. However, electronic distribution was practiced even during the time when the Beauregard case was decided and patent drafters therefore soon tailored their claimed "computer readable medium" to encompass more than just floppy disks, ROMs, or other stable storage media, by extending the concept to information encoded on a carrier wave (such as radio) or transmitted over the Internet.

Two important developments have occurred since the mid and late 1990s, which have a drastic impact on the viability of "Beauregard" claims. First, in In re Nuijten,[5] the Federal Circuit held that signals were not patent eligible, because their ephemeral nature kept them from falling within the statutory categories of 35 U.S.C. § 101, such as articles of manufacture. That eliminated much of the market for Beauregard claims to computer programs electronically distributed.

Second, the decisions of the Supreme Court leading up to Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International[6] appeared to exclude what amounted to a patent on information from the patent system. In CyberSource Corp. v. Retail Decisions Inc.,[7] the Federal Circuit first held a method for detecting credit card fraud patent ineligible and then held a corresponding Beauregard claim similarly patent ineligible because it too simply claimed a “mere manipulation or reorganization of data.”[8] After the Cybersource decision, the Supreme Court’s decision in the Alice case made the status of Beauregard claims even more uncertain. At the very least, if the underlying method claim is not patent eligible, recasting the claim in Beauregard format will not improve the patent eligibility.

Claims of this type have been allowed by the European Patent Office (EPO). However, a more general claim form of "a computer program for instructing a computer to perform the method of [allowable method claim]" is allowed, and no specific medium needs to be specified.[9]

The UK Patent Office (aka IPO) began to allow computer program claims following this revised EPO practice, but then began to refuse them in 2006 after the decision of Aerotel/Macrossan. The UK High Court overruled this practice by decision,[10] so that now they are again allowable in the UK as well, as they have been continuously at the EPO.

Exhausted combination

In United States patent law, an exhausted-combination claim comprises a claim (usually a machine claim) in which a novel device is combined with conventional elements in a conventional manner.

An example would be a claim to a conventional disc drive with a novel motor,[11] to a personal computer (PC) containing a novel microprocessor,[12] or to a conventional grease gun having a new kind of nozzle.[13][Notes 2] A far-fetched example, but one that illustrates the principle, would be a claim to an automobile containing a novel brake pedal.

The Federal Circuit held in 1984 that the doctrine of exhausted combination is outdated and no longer reflects the law.[14][15] In its 2008 decision in Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc.,[16] however, the Supreme Court seems to have assumed without any discussion that its old precedents are still in force, at least for purposes of the exhaustion doctrine.[Notes 3]

Exhausted combination claims can have practical significance in at least two contexts. First is royalties. On the one hand, there is the possibility of the royalty base being inflated (since a car containing a novel brake pedal sells for more than the brake pedal itself would) or creating at least an opportunity to levy royalties at more than one level of distribution (an issue in the Quanta case). On the other hand, the royalties may not be just without a proper combination of elements. A second context is that of statutory subject matter under the machine-or-transformation test. By embedding a claim that does not satisfy the machine-or-transformation test in a combination with other equipment, it may make it possible to at least appear to satisfy that test.[17]

Jepson

In United States patent law, a Jepson claim is a method or product claim where one or more limitations are specifically identified as a point of novelty, distinguishable over at least the contents of the preamble. They may read, for instance, "A system for storing information having (...) wherein the improvement comprises:". The claim is named after the case, Ex parte Jepson, 243 Off. Gaz. Pat. Off. 525 (Ass't Comm'r Pat. 1917). They are similar to the "two-part form" of claim in European practice prescribed by Rule 43(1) EPC.[18]

In a crowded art, a Jepson claim can be useful in calling the examiner's attention to a point of novelty of an invention without requiring the applicant to present arguments and possibly amendments to communicate the point of novelty to the Examiner. Such arguments and amendments can be damaging in future litigation, for example as in Festo.

On the other hand, the claim style plainly and broadly admits that that subject matter described in the preamble is prior art, thereby facilitating the examiner's (or an accused infringer's) arguments that the improvement is obvious in light of the admitted prior art, as per 35 U.S.C. § 103(a). Prosecutors and applicants are hesitant to admit anything as prior art for this reason, and so this claim style is seldom used in modern practice in the U.S.

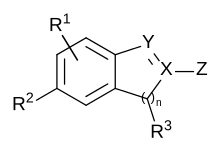

Markush

Mainly but not exclusively used in chemistry, a Markush claim or structure is a claim with multiple "functionally equivalent" chemical entities allowed in one or more parts of the compound. According to "Patent Law for the Nonlawyer" (Burton A. Amernick; 2nd edition, 1991),

- "In claims that recite... components of compositions, it is sometimes important to claim, as alternatives, a group of constituents that are considered equivalent for the purposes of the invention.... It has been permissible to claim such an artificial group, referred to as a 'Markush Group,' ever since the inventor in the first case... won the right to do so."

If a compound being patented includes several Markush groups, the number of possible compounds it covers could be vast. No patent databases generate all possible permutations and index them separately. Patent searchers have the problem, when searching for specific chemicals in patents, of trying to find all patents with Markush structures that would include their chemicals, even though these patents' indexing would not include the suitable specific compounds. Databases enabling such searching of chemical substructures are indispensable.

Markush claims were named after Eugene Markush, the first inventor to use them successfully in a U.S. patent (see, e.g., U.S. Patent Nos. 1,506,316, 1,982,681, 1,986,276, and 2,014,143), in the 1920s to 1940s. See Ex parte Markush.[19]

According to the USPTO, the proper format for a Markush-type claim is : "selected from the group consisting of A, B and C." [20]

In August 2007, the USPTO unsuccessfully proposed a number of changes to the use of Markush-type claims.[21]

Means-plus-function

A means-plus-function claim is a claim including a technical feature expressed in functional terms of the type "means for converting a digital electric signal into an analog electric signal". A variant known as a "step-plus-function" claim style may be used to describe the steps of a method invention ("step for converting... step for storing...")

Means-plus-function claims are governed by the various statutes and laws of the country or countries in which a patent application is filed.

United States

In the U.S., means-plus-function claims are governed by various federal statutes, including 35 U.S.C. 112, paragraph 6, which reads: "An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof." Interpreting this seemingly simple statement has proven to be a surprisingly difficult task.

First, most claim styles are intended to be a succinct summary of the invention that stands alone and is interpreted largely on their own merits. By contrast, this claim style tacitly imports and relies upon the entire specification for interpretation, which is implausible (and also the reason for disallowing "omnibus" patent claims - see below).

Second, the courts, as well as the patent office, have been somewhat inconsistent in specifying rules for when the "means-plus-function" interpretation is triggered. A claim reciting "means for [a specific function]" probably triggers the rule. The courts have construed variations like "means of," "means by," or even "component for [a specific function]", with inconsistent results.

Third, the courts and the patent office have rapidly proposed, modified, and deprecated several tests for determining the scope of "equivalents" of a means-plus-function element. This problem is exacerbated by the use of the term "equivalents," which is apparently similar to but not identical to the use of the same term in the "doctrine of equivalents" test of patent infringement.

Extensive analysis has been done on interpretation of the scope and requirements of the means- and step-plus-function claim style.[22][23] Despite the complexity of this area of law, which includes many ambiguous and logically contradictory opinions and tests, many practitioners and patent applicants still use this claim style in an independent claim if the specification supports such means-plus-function language.[22][23]

Omnibus

A so-called omnibus claim is a claim including a reference to the description or the drawings without stating explicitly any technical features of the product or process claimed. For instance, an omnibus claim may read as "The invention substantially as herein described",[24] "Apparatus as described in the description" or "An x as shown in Figure y".

European Patent Organisation

Omnibus claims are allowed under the EPC, but only "when they are absolutely necessary".[25][26][27] Other patent offices, such as the United Kingdom Patent Office, are more receptive to this claim style.[28]

United States

Under U.S. patent law, omnibus claims are categorically disallowed in utility patents, and examiners will reject them as failing to "particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention" as required by 35 USC 112 paragraph 2. By contrast, design patents and plant patents are required to have one claim, and in omnibus form ("the ornamental design as shown in Figure 1.")

Product-by-process

A product-by-process claim is a claim directed to a product where the product is defined by its process of preparation, especially in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries.[29] They may read for instance "Product obtained by the process of claim X," "Product made by the steps of . . .," and the like.

According to the European practice, they should be interpreted as meaning "Product obtainable by the process of claim...". They are only allowable if the product is patentable as such, and if the product cannot be defined in a sufficient manner on its own, i.e. with reference to its composition, structure or other testable parameters, and thus without any reference to the process.

The protection conferred by product-by-process claims should not be confused with the protection conferred to products by pure process claims, when the products are directly obtained by the claimed process of manufacture.[30]

In the U.S., the Patent and Trademark Office practice is to allow product-by-process claims even for products that can be sufficiently described with structure elements.[31] However, since the Federal Circuit's 2009 decision in Abbott Labs. v. Sandoz, Inc., 566 F.3d 1282, 1300 (Fed. Cir. 2009), such claims are disadvantageous compared to "true product" claims. To prove infringement of a product-by-process claim under Abbott, a patentee must show that a product meets both the product and the process elements of a product-by-process claim. To invalidate a product-by-process claim, however, an accused infringer need only show that the product elements, not the process elements, were present in the prior art. This can be compared to a "true product" claim, where all limitations must be proven to invalidate the claim.

Programmed computer

A programmed computer claim is one in the form—a general-purpose digital computer programmed to carry out (such and such steps, where the steps are those of a method, such as a method to calculate an alarm limit or a method to convert BCD numbers to pure binary numbers). The purpose of the claim is to try to avoid case-law holding certain types of method to be patent-ineligible. The theory of such claims is based on "the legal doctrine that a new program makes an old general purpose digital computer into a new and different machine."[32] The argument against the validity of such claims is that putting a new piano roll into an old player piano does not convert the latter into a new machine. See Piano roll blues.

Reach-through

A reach-through claim is one that attempts to cover the basic research of an invention or discovery.[33] It is an "attempt to capture the value of a discovery before it may be a full invention." [34] Specifically, a reach-through claim is one in which "claims for products or uses for products when experimental data is provided for screening methods or tools for the identification of such products." [35]

A reach through claim can be thought of as an exception to the general rule about claims.[36]

An example of a denied claim was when the United States Federal Circuit refused to recognize a reach-through claim for Celebrex.[35]

Signal

A signal claim is a claim for an electromagnetic signal that can, for example, embody information that can be used to accomplish a desired result or serve some other useful objective. One claim of this style might read: "An electromagnetic signal carrying computer-readable instructions for performing a novel method... "

In the United States, transitory signal claims are no longer statutory subject matter under In re Nuijten.[37] A petition for rehearing en banc by the full Federal Circuit was denied in February 2008,[38] and a petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court was denied the following October.[39]

In contrast to the situation in the U.S., European Patent Office's Board of Appeal 3.4.01 held in its decision T 533/09 that the European Patent Convention did not as such exclude the patentability of signals, so that signals could be claimed. The Board acknowledged that a signal was neither a product nor a process,[40] but could fall under the definition of « physical entity » in the sense of Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G 2/88.[41]

Swiss-type

In Europe, a Swiss-type claim or "Swiss type of use claim" is a formerly used claim format intended to cover the first, second or subsequent medical use (or indication of efficacy) of a known substance or composition.

Consider a chemical compound which is known generally, and the compound is known to have a medical use (e.g. in treating headaches). If it is later found to have a second medical use (such as combating hair loss), the discoverer of this property will want to protect that new use by obtaining a patent for it.

However, the compound itself is known and thus could not be patented; it would lack novelty under Article 54 EPC (before the entry into force of the EPC 2000 and new Article 54(5) EPC). Nor could the general concept of a medical formulation including this compound. This is known from the first medical use, and thus also lacks novelty under EPC Article 54. Only the particular method of treatment is new. However methods for treatment of the human body are not patentable under European patent law (Article 53(c) EPC). The Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office solved this by allowing claims to protect the "Use of substance X in the manufacture of a medicament for the treatment of condition Y".[42] This fulfilled the letter of the law (it claimed the manufacture, not the medical treatment), and satisfied the EPO and applicants, in particular the pharmaceutical industry. Meanwhile, in view of new Article 54(5) EPC, on 19 February 2010, the EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal issued its decision G 2/08 and decided at that occasion that applicants may no longer claim second medical use inventions in the Swiss format.[43]

In courts, the validity of claims drafted as if they were directed to a manufacturing process, when they are directed to a non-patentable subject-matter, remains to be seen. Because such claims had first been devised in Switzerland, they became known as "Swiss-type claims".

In certain countries, including New Zealand,[44] the Philippines,[45] China, Israel and Canada, methods of medical treatment are not patentable either (see MOPOP section 12.04.02),[46] however "Swiss-type claims" are allowed (see MOPOP section 12.06.08).[47]

Notes

- ↑ The court remanded to the PTO on the agency's motion for permission to reopen examination in the light of proposed Guidelines on patent-eligibilty. The court did not expressly decide whether Beauregard claims are patent-eligible.

- ↑ In Lincoln Engineering, the inventor invented a new and improved coupling device to attach a nozzle to a grease gun. The patent, however, claimed the whole combination of grease gun, nozzle, and coupling. The Supreme Court stated that "the improvement of one part of an old combination gives no right to claim that improvement in combination with other old parts which perform no new function in the combination." It then concluded that the inventor’s "effort, by the use of a combination claim, to extend the monopoly of his invention of an improved form of chuck or coupler to old parts or elements having no new function when operated in connection with the coupler renders the claim void."

- ↑ The Court held that the sale of a patented microprocessor "exhausted" not only the microprocessor patent (i.e., removed the legal effectiveness of the patent's statutory monopoly) but also the patent on the personal computer (PC) containing the microprocessor, because both were based on the same inventive concept. It is therefore unclear what effect, if any, the Quanta decision will have on the validity of exhausted combination claims.

References

- ↑ In re Beauregard, 53 F.3d 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1995).

- ↑ See Victor Siber and Marilyn S. Dawkins, Claiming Computer-Related Inventions As Articles of Manufacture, 35 IDEA 13 (1994). The Beauregard case was a test case brought by Victor Siber, IBM's chief patent lawyer at the time, to test the legal theories advanced in his IDEA article.

- ↑ Ex parte Bo Li, Appeal 2008-1213, at 9 (BPAI 2008) and MPEP 2105.01, I.

- ↑ Richard H. Stern, An Attempt To Rationalize Floppy Disk Claims, 17 J. Marshall J. Computer & Info. L. 183 (1998).

- ↑ 500 F.3d 1346 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

- ↑ 573 U.S. __, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

- ↑ 654 F. 3d 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

- ↑ The PTO’s internal appeals board had held, “A computer readable media including program instructions . . . to an otherwise nonstatutory process claim is insufficient to make it statutory.”Ex parte Cornea-Hasegan, 89 U.S.P.Q.2d 1557, 1561 (B.P.A.I. 2009); accord Ex parte Mewherter, 107 U.S.P.Q.2d 1857, 1859 (PTAB 2013).

- ↑ Technical Board of Appeal Decision T1173/97

- ↑ 2008 EWHC 85 (Pat).

- ↑ Minebea Co. v. Papst, 444 F. Supp. 2d 68 (D.D.C. 2006).

- ↑ Quanta Computer, Inc. v. LG Electronics, Inc.,128 S. Ct. 2109 (2008).

- ↑ Lincoln Engineering Co. v. Stewart-Warner Corp., 303 U.S. 545 (1938).

- ↑ Radio Steel & Mfg. Co. v. MTD Products, Inc., 731 F.2d 840, 845 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

- ↑ In re Bernhardt, 417 F.2d 1395 (Ct. Cus. & Pat. App. 1969).

- ↑ 128 S. Ct. 2109 (2008).

- ↑ Richard H. Stern, Tales From the Algorithm War: Benson to Iwahashi, It's Deja Vu All Over Again, 18 AIPLA Q.J. 371 (1991).

- ↑ http://www.1201tuesday.com/1201_tuesday/2009/06/jepson.html

- ↑ Ex parte Markush, 1925 Dec. Comm’r Pat. 126, 128 (1924).

- ↑ MPEP Section 803.02

- ↑ Notice of Proposed Rulemaking regarding Examination of Patent Applications That Include Claims Containing Alternative Language

- 1 2 Armstrong, James. Essentials of Drafting US Patent Specifications and Claims. pp. 47–51. ISBN 4-8271-0556-1.

- 1 2 Landis, John. Mechanics of Patent Claim Drafting. p. 41.

- ↑ "2.2.1 Claims with explicit references to the description or drawings". Guidelines for Search and Examination at the EPO as PCT Authority. European Patent Office. 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ↑ Rule 43(6) EPC

- ↑ Decision T 150/82, O.J. EPO issue: 1984,309.

- ↑ Guidelines for Examination in the EPO, section f-iv, 4.17 : "References to the description or drawings"

- ↑ UK IPO Manual of Patent Practice 14.124

- ↑ Walsh, G.; Murphy, B., eds. (1999). Biopharmaceuticals, an Industrial Perspective (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 250. ISBN 0792357469.

A product-by-process patent is one which claims the product in terms of a particular process of preparation described in the patent.

- ↑ Article 64(2) EPC

- ↑ See 3 Chisum on Patents § 8.05[2][a]-[c]

- ↑ In re Johnston, 502 F.2d 765, 773 (CCPA 1974), from the dissenting opinion.

- ↑ Patently-O web site

- ↑ Dorsey law firm web site

- 1 2 Univ. of Rochester v. G.D. Searle & Co., 358 F3d 916, 69 USPQ2d 1886, 1896 (Fed Cir 2004); see also Univ. of Rochester v. G.D. Searle & Co., 68 USPQ2d 1424, 1433 (W.D.N.Y. 2003)

- ↑ National academies web site Power Point required.

- ↑ In re Nuijten. 500 F.3d 1346 (Fed. Cir. 2007)

- ↑ Dennis Crouch, Signal Claims Are Not Patentable: Nuijten Stands -- Rehearing Denied, Patently-O, February 11, 2008.

- ↑ Nuijten v. Dudas, no. 07-1404, (docket). Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ↑ T 0533/09, 7.4 (EPO Board of Appeal 3.4.01 11 February 2014) (“(...) la Chambre ne saurait associer un signal, en l’occurrence un train d'impulsions électrique, à la notion de produit. De même, (...) la Chambre ne saurait considérer qu’un signal rentre dans la catégorie des procédés. (Translation: (...) the Board could not associate a signal, namely an electric pulse train, to the concept of product. In the same manner, (...) the Board could not consider that a signal falls into the category of processes.)”).

- ↑ T 0533/09, 7.4 (EPO Board of Appeal 3.4.01 11 February 2014) (“(...) la Chambre considère que le train d'impulsions revendiqué est de nature concrète dans la mesure où il résulte de la modulation d'un signal électrique (décharge d'un condensateur dans un but de défibrillation) et que son intensité est mesurable à tout instant. Un tel signal tombe ainsi bel et bien sous la définition de « physical entity » au sens de la décision G 2/88, dans sa version d’origine. (Translation: (...) the Board considers that the claimed pulse train is of a concrete nature since it results from the modulation of an electric signal (discharging of a capacitor for carrying out defibrillation) and its intensity can be measured at any time. Such a signal falls therefore within the definition of « physical entity » in the sense of Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G 2/88, in its original version.)”).

- ↑ Opinion G5/83 of the EPO Enlarged Board of Appeal

- ↑ "Patents Act 1977: Second medical use claims", UK IPO, Practice notices. Consulted on October 3, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.iponz.govt.nz/cms/patents/patent-topic-guidelines/2004-business-updates/2009-business-updates/guidelines-for-the-examination-of-swiss-type-claims/ Archived March 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Intellectual Property Office of the Philippines (IPHL), Examination Guidelines For Pharmaceutical Patent Applications Involving Known Substances, Part 9

- ↑ CIPO - Manual of Patent Office Practice - Chapter 12

- ↑