Lisbon massacre

| Lisbon massacre | |

|---|---|

|

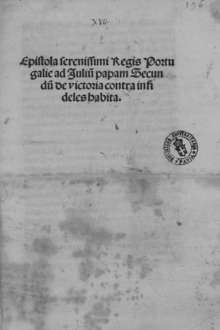

A German woodcut depicting the massacre, one of the few woodcuts that survived the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and the fire at Torre do Tombo | |

| Location | Church of São Domingos, Lisbon |

| Date | 19 to 21 April 1506 |

| Deaths | 1900+ |

The Lisbon massacre, alternatively known as the Lisbon pogrom or the 1506 Easter Slaughter was an incident in April, 1506, in Lisbon, Portugal in which a crowd of Catholics, as well as foreign sailors who were anchored in the Tagus, persecuted, tortured, killed, and burnt at the stake hundreds of people who were accused of being Jews and, thus, guilty of deicide and heresy. This incident took place thirty years before the establishment of the Inquisition in Portugal and nine years after the Jews were forced to convert to Roman Catholicism in 1497, during the reign of King Manuel I.

Background

In the years that followed the banishment of the Jews from Castile and Aragon in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs, about 93,000 Jews took refuge in neighbouring Portugal. King Manuel I was by far more tolerant toward the Jewish community but, under pressure from Spain, made their conversion to Roman Catholicism compulsory in 1497.

The massacre

The massacre began, as it is reported, in the São Domingos de Lisboa Convent on Sunday, 19 April 1506. The faithful were praying for the end of the drought and plague that swept the country when someone swore they had seen the illuminated face of Christ on the altar — a phenomenon that could only be explained by the Catholics present as a message from the Messiah, a miracle.

A New Christian, one of the converted Jews, thought otherwise, and voiced his opinion that it had been only the reflection of a candle on the crucifix. The men gathered for Mass, hearing this, grabbed the man by his hair and brought him outside the church where he was beaten to death by the crowd and his body was burnt in Rossio (one of the main squares of central Lisbon).

From that point the New Christians, who were already not trusted by the population, became the scapegoats for the drought, famine and plague. Dominican friars promised absolution for sins committed over the previous 100 days to those who killed the "heretics", and a crowd of more than 500 people (many of them sailors from Holland, Zeeland and Germany) gathered and killed all the New Christians they could find on the streets, burning their bodies by the Tagus or in Rossio. That Sunday, more than 500 people were violently sent to their deaths.

The Court and the King had earlier left Lisbon for Abrantes in order to escape the plague, and were absent when the massacre began. King Manuel I was in Avis when he was informed of the event in Lisbon, and dispatched magistrates to try to put an end to the bloodbath. Meanwhile, in Lisbon, the small group of authorities present were unable to intervene, as the crowd grew and the violence spread.

By Monday, 20 April, more locals had joined the crowd, which carried on the massacre with even more violence. The New Christians, no longer found on the streets, were dragged from their houses and from churches and, along with their wives, sons and daughters, were burnt in the public squares alive or dead. Not even infants were spared, as the crowd ripped them to pieces or threw them against the walls. The crowd proceeded to loot the houses, stealing all the gold, silver and linens they could find. More than 1000 people were killed on the second day. There is also record that more than Jews were killed that day. Some accused their neighbours of heresy, and these unfortunates met the same fate as the New Christians.

On Tuesday, members of the court arrived at the city and rescued some of the New Christians. João Rodrigues Mascarenhas, the King's Squire, was killed by mistake in the massacre, and this triggered the arrival of the Royal Guard. The death count had, however, already reached more than 1,900. Aires da Silva and D. Álvaro de Castro, head of the Lisbon Freguesia and Governor, respectively, were among those who tried to stop the crowd, and they were backed by the Prior of Crato and D. Diogo Lopo, Baron of Alvito, who had special powers from the King to execute members of the crowd.

Aftermath

Some Portuguese were arrested and hanged, while others had all their possessions confiscated by the Crown. The foreigners returned to their ships with their plunder and sailed away. The two seditionist Dominican friars who had incited the massacre were stripped of their religious orders and were burnt at the stake.

There are reports that the São Domingos Convent was closed down during the eight years that followed, and all the representatives of the city of Lisbon were expelled from the Council of the Crown—Lisbon had had a seat in the Council since 1385, when King John I gave the city that privilege.

Following the massacre, a climate of suspicion against New Christians pervaded Portugal. The Inquisition was established thirty years afterward; many families of Jewish ancestry either escaped or were banished from the country. Even banished, they still had to pay for their emigration; they had to leave or sell their properties to the Crown, travelling only with the luggage they could carry.

After the massacre New Christians of Jewish ancestry still felt deep allegiance to the Portuguese monarch.[1]

References

- ↑ Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Elisheva Carlebach: Jewish History and Jewish Memory: Essays in Honor of Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, 1998, UPNE, ISBN 0-87451-871-7, p. 6–7

Bibliography

- GOIS, Damião de (1749). Chronica de el-rei D. Emanuel (vol. II) (in Portuguese).

- Richard Zimler The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon (1998)