Leukocytosis

| Leukocytosis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, pathology |

| ICD-10 | D72.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 288.3, 288.6x |

| DiseasesDB | 33024 |

| MeSH | D007964 |

Leukocytosis is white cells (the leukocyte count) above the normal range in the blood.[1][2] It is frequently a sign of an inflammatory response,[3] most commonly the result of infection, but may also occur following certain parasitic infections or bone tumors. It may also occur after strenuous exercise, convulsions such as epilepsy, emotional stress, pregnancy and labour, anesthesia, and epinephrine administration.[1]

There are five principal types of leukocytosis:[4]

- Neutrophilia (the most common form)[5]

- Lymphocytosis

- Monocytosis

- Eosinophilia

- Basophilia

This increase in leukocyte (primarily neutrophils) is usually accompanied by a "left shift" in the ratio of immature to mature neutrophils. The proportion of immature leukocytes increases due to proliferation and release of granulocyte and monocyte precursors in the bone marrow which is stimulated by several products of inflammation including C3a and G-CSF. Although it may indicate illness, leukocytosis is considered a laboratory finding instead of a separate disease. This classification is similar to that of fever, which is also a test result instead of a disease. "Right shift" in the ratio of immature to mature neutrophils is considered with reduced count or lack of "young neutrophils" (metamyelocytes, and band neutrophils) in blood smear, associated with the presence of "giant neutrophils". This fact shows suppression of bone marrow activity, as a hematological sign specific for pernicious anemia and radiation sickness.[6]

A leukocyte count above 25 to 30 x 109/L is termed a leukemoid reaction, which is the reaction of a healthy bone marrow to extreme stress, trauma, or infection. It is different from leukemia and from leukoerythroblastosis, in which either immature white blood cells (acute leukemia) or mature, yet non-functional, white blood cells (chronic leukemia) are present in peripheral blood.

Leukocyte counts

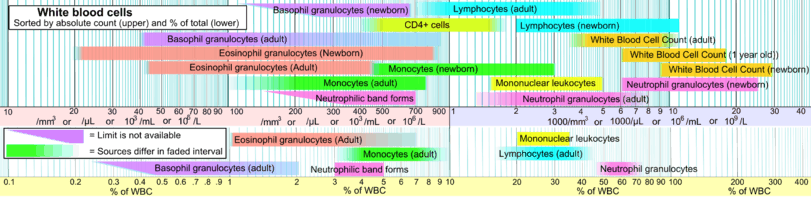

Below are blood reference ranges for various types leucocytes/WBCs.[7] The 97.5 percentile (right limits in intervals in image, showing 95% prediction intervals) is a common limit for defining leukocytosis.

Classification

Leukocytosis can be subcategorized by the type of white blood cell that is increased in number. Leukocytosis in which neutrophils are elevated is neutrophilia; leukocytosis in which lymphocyte count is elevated is lymphocytosis; leukocytosis in which monocyte count is elevated is monocytosis; and leukocytosis in which eosinophil count is elevated is eosinophilia.[8]

An extreme form of leukocytosis, in which the WBC count exceeds 100,000/µL, is leukostasis. In this form there are so many WBCs that clumps of them block blood flow. This leads to ischemic problems including transient ischemic attack and stroke.

Causes

| Causes of leukocytosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophilic leukocytosis (neutrophilia) |

| |||

| Eosinophilic leukocytosis (eosinophilia) |

| |||

| Basophilic leukocytosis Basophilia |

(rare)[8] | |||

| Monocytosis | ||||

| Lymphocytosis |

| |||

Leukocytosis is very common in acutely ill patients. It occurs in response to a wide variety of conditions, including viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infection, cancer, hemorrhage, and exposure to certain medications or chemicals including steroids.

For lung diseases such as pneumonia and tuberculosis, WBC count is very important for the diagnosis of the disease, as leukocytosis is usually present.

The mechanism that causes leukocytosis can be of several forms: an increased release of leukocytes from bone marrow storage pools, decreased margination of leukocytes onto vessel walls, decreased extravasation of leukocytes from the vessels into tissues, or an increase in number of precursor cells in the marrow.

Certain medications, including corticosteroids, lithium and beta agonists, may cause leukocytosis.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 Rogers, Kara, ed. (2011), "Leukocytosis definition", Blood: Physiology and Circulation, Chicago: Britannica Educational Publishing, p. 198, ISBN 978-1-61530-250-5, retrieved 12 November 2011

- ↑ TheFreeDictionary > Leukocytosis Citing: Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, 2008 and The American Heritage Medical Dictionary, 2007

- ↑ Porth, Carol Mattson (2011), "White blood cell response", Essentials of Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States (3rd ed.), Philadelphia: Wolters Klower Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp. 64–65, ISBN 978-1-58255-724-3, retrieved 13 November 2011

- ↑ Zorc, Joseph J, ed. (2009), "Leukocytosis", Schwartz's Clinical Handbook of Pediatrics (4th ed.), Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p. 559, ISBN 978-0-7817-7013-2, retrieved 12 November 2011

- ↑ Schwartz, M. William, ed. (2003), "Leukocytosis", The 5-Minute Pediatric Consult (3rd ed.), Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p. 54, ISBN 0-7817-3539-4, retrieved 12 November 2011

- ↑ Lutan, Vasile. Fiziopatologie medicală. Vol. 2, 31.3.2.1. Leucocitozele; http://library.usmf.md/ebooks.php?key=b11

- ↑ Specific references are found in article Reference ranges for blood tests#White blood cells 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Table 12-6 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson, Robbins Basic Pathology, Philadelphia: Saunders, ISBN 1-4160-2973-7 8th edition.

- ↑ Leukocytosis: Basics of Clinical Assessment, American Family Physician. November 2000.