Legalism (Chinese philosophy)

| Legalism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Statue of pivotal reformer Shang Yang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 法家 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | The two basic meanings of Fa are "method" and "standard". Jia can mean "school of thought", but also "specialist" or "expert", this being the usage that has survived in modern Chinese.[1][2][3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Legalism |

|---|

|

|

Texts |

|

Founding figures |

|

Han figures |

|

Later figures |

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

Fǎ-Jiā (法家) or Legalism is one of the six classical schools of thought in Chinese philosophy that developed during the warring states period and was first labeled by Chinese philosopher Han Fei during the 3rd century BCE. This school of thought placed emphasis on political reform through fixed and transparent rules and realistic consolidation of the wealth and power of the state with the goal of achieving increased order and stability. It does not have a moral foundation nor does it describe how society ideally should function, but rather examines the present state of the government.[4]

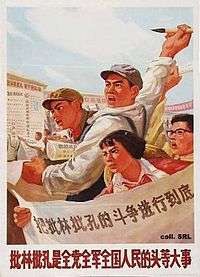

Han Fei's essays (called the Han Feizi) are commonly thought of as the greatest of all "Legalist" texts, bringing together his predecessors ideas into a coherent ideology.[5][6] This ideology attracted the attention of the First Emperor[7] and it is believed that this school of thought laid the foundation for the Chinese bureaucratic empire[8] that would surpass that of most other national governments until near the end of the eighteenth century.[9] Legalism has remained highly influential in administration, policy and legal practice in China.[10] Endorsement for this school of thought peaked under Mao Zedong, who hailed it as a “progressive” intellectual current.[11] Modernly the Legalist School has been considered by some as akin to Realpolitikal thought of ancient China,[12] and often compared with Machiavelli[13] for its (sometimes blunt) realism.

Historical background

The earliest Zhou kings kept a "firm personal hand" on the government, depending on their personal capacities, personal relations between the ruler and his ministers, and upon military might. The technique of centralized government being so little developed, they deputed authority to feudal lords.[14] "Chinese feudal society" was divided between the masses and the hereditary noblemen, the former being "objects of an enlightened benevolent political trusteeship", the latter being placed to obtain office and political power. They owed allegiance to the local prince, who owed allegiance to the Son of Heaven.[15] When the Zhou kings could no longer grant new fiefs, their power began to decline and vassals began to identify with their own regions. An alliance between rebel nobles and unsinicized Rong ultimately forced the Zhou king east.[16] In the Spring and Autumn period officials began reforms in order to support the authority, states, and militaries of the kings.[17]

With the decay of the Zhou line schismatic hostility occurred between the Chinese states. In the Spring and Autumn period aristocratic families became very important, by virtue of their ancestral prestige wielding great power and proving a divisive force.[14] A new type of ruler emerged intent on breaking the power of the aristocrats and reforming their state's bureaucracies. Those that failed were conquered of deposed.[18][19]

Disenfranchised or opportunist aristocrats were increasingly attracted by the reform-oriented rulers,[20] bringing with them a philosophy concerned foremost with organizational methodology.[18] Rulers began to directly appoint incumbent state officials to provide advice and management, leading to the decline of inherited privileges and bringing fundamental structural transformations as a result of what may be termed "social engineering from above."[3][21]

"Legalism" became significant because of the successful reforms led by its politicians. It promoted the rapid growth[22] of the Qin state state that applied "Legalism" most consistently, unifying China, and "Legalism" fell along with them. But Legalist tendencies remained in the supposedly Confucian imperial government.[23]

In contrast with Confucianism, the "Legalist" approach is primarily at the institutional level, aiming for a clear power structure, consistently enforced objective rules and regulations, and in the Han Feizi, engaging in sophisticated manipulation tactics to enhance power bases.[24] A basic difference between Confucianism and "Legalism" is in the authority to make policy. Proposing a return to feudal ideals, albeit his nobleman being anyone who possessed virtue,[15] Confucians granted this to "wise and virtuous ministers", allowed to "govern as they saw fit". Shen Buhai and Shang Yang monopolized policy in the hands of the ruler,[25] and Qin legal documents focus on rigorous control of local officials, and the keeping of written records.[26]

Early history

Though standard treatments of the "Legalist" school oppose law with the ritual of the Confucians,[27] a more critical examination of the written codes of the Warring States period reveals that they emerged from a religious and ritual background, oaths being the origin of control of the individual and household. The early "Legalist" text Guanzi couches its arguments in undisguised moral language.

R. Eno of Indiana University writes that "If one were to trace the origins of Legalism as far back as possible, it might be appropriate to date its beginnings to the prime ministership of Guan Zhong, chief aide to the first of the hegemonic lords of the Spring Autumn period, Duke Huan of Qi (r. 685 - 643)."[28] The reforms of Guan Zhong (720-645 BCE) applied levies and economic specializations at the village level instead of the aristocracy, and shifted administrative responsibility to professional bureaucrats.

Allyn Rickett, translator of the Guanzi text bearing his name considers him to have been one of the "chief models for a new type of professional bureaucrat and political adviser who came to the fore as the old hereditary officials proved inadequate for the task..." On the other hand, Rickett judges him to have been "at least in most respects" an "ideal Confucan minister".[29] The Ming dynasty agricultural scientist Xu Guangqi frequently cited the Xunzi and Guanzi, and made use of rewards and punishments along the lines of the "Legalists".[30]

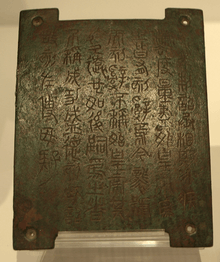

Zichan(d. 496 BCE) was a high minister of the central Zhou state Zheng during the late Spring and Autumn period. Zichan reformed the state on a legal basis, enacting a harsh criminal code.[31] He cast the state's code of law in bronze vessel to be displayed in public[32] as a demonstration of permanence and incorruptibility, a first among the Zhou states. Shang Yang would make similar such gestures two hundred years later, and like him reformed agricultural and commercial laws and changed social norms, and discouraged superstition.[33][34] Confucius(551 – 479 BCE) admired him; when a fire blaze had destroyed a part of the land, the duke wanted to undergo expensive sacrificial offerings, but Zichan admonished him to exert a more virtuous government.[31]

Feng Youlan considered Mozi (470–391BC) to be "one of the most important figures of Chinese history."[35] Most scholars date Mozi at around 470–391 BCE, being born around the time of the death of Confucius. Later perniciously criticized by Mencius,[36] the Mohist school otherwise "died out during the decades following the Qin conquest of 221", but was very influential in the Warring States period. Mozi might be considered the first to have "offered a strong intellectual challenge to Confucianism,"[37] and is generally considered to have been its main contender "during the two centuries prior the Qin hegemony."[38]

The Mohists advocated a unified, utilitarian ethical and political order, positing some of its first theories and initiating philosophical debate in China. To unify moral standards, they supported a "centralized, authoritarian state led by a virtuous, benevolent sovereign managed by a hierarchical, merit-based bureaucracy",[39] That social order is paramount seems to be implicit, recognized by all.[40] Compared with Plato, in their hermeneutics they contained the philosophical germs of what Sima-Tan would term the "Fa-School" ("Legalists"), contributing to the political thought of contemporary reformers.[39] They argued against nepotism, and for universal standards as represented by the centralized state, saying "If one has ability, then he is promoted. If he has no ability, then he is demoted. Promoting public justice and casting away private resentments – this is the meaning of such statements."

Rectification of names

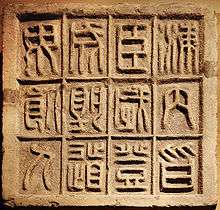

The 12 characters on this slab of floor brick affirm that it is an auspicious moment for the First Emperor to ascend the throne, as the country is united and no men will be dying along the road.

Legalism is distinguished by its efforts to obtain objectivity.[41] "Law" (standards) and administration in "Legalism" are based on "matching language to reality." Declarations, such as those of a judge, produce social reality. Language, such as that of legal code, is linked to social control. This is relatable to the Confucian rectification of names, which arguably originates in Mozi. If words are not correct, they do not correspond to reality, and regulation fails. Law is "purified", rectified, or technically regulated language.[42][43] For Mozi, if language is made objective, then language itself could serve as a source of information, and argued that in any dispute of distinctions, one party must be right and one wrong.[44] For Shen Buhai, correct or perverse words will order or ruin the state.[45] In an ideal situation, the "Legalist" judge does not weigh evidence, but simply defines crimes in a purely administrative fashion.[46]

The "Legalistic" version of the rectification of names is Fa.[47] Mozi advocated language standards appropriate for use by ordinary people.[48] Seemingly originating in Guan Zhong, for Guan Zhong and the Mohists, Fa recommended objective, reliable, easily used,[49] publicly accessible standards, opposing what Sinologist Chad Hansen terms the "cultivated intuition of self-admiration societies", expert at chanting old texts. However, it could complement any traditional scheme, and Guan Zhong uses Fa alongside the Confucian Li. What Fa made possible was the accurate following of instructions.[47] With minimal training, anyone can use Fa to perform a task or check results.[50] For the most part Confucianism does not elaborate on it, though the idea of norms themselves are older and Han Confucians embraced Fa as an essential element in administration.[47][51]

Providing a clear standard,[52] Fa compares something against itself, and then judges whether the two are similar, just as with the use of the compass or the L-square.[39][53] This constituted the basic conception of Mohists practical reasoning and knowledge. What matches the standard is the particular object, and thus correct; what doesn't is not. Knowledge is a matter of "being able to do something correctly in practice" — and in particular, being able to distinguish various kinds of things from one another. Evaluating correctness is thus determining whether distinctions have been drawn properly. Its aim is not an intellectual grasp of a definition or principle, but the practical ability to perform a task (dao) successfully.[39] They proposed its use for reward and punishment, promotion and censure, drawing from the general population.[54]

Fa or "standards"

The Mohists and the Guanzi text attributed to Guan Zhong are of particular importance to understanding Fa,[55] meaning "to model on" or "to emulate".[56] Dan Robins of the University of Hong Kong writes that fa "became important in early Chinese philosophy largely because of the Mohists".[57] In principle, if their roots in Mozi are considered, the "Legalists" might all be said to use Fa in the same (administrative) fashion.[58]

In "The Seven Kinds of Standard", the Guanzi text lists seven kinds of Fa, namely "To be true, sincere, generous, giving, temperate, and compassionate."[55] Likening standards to the square and plumb-line,[59] the Guanzi, and more especially the Mohists explain fa as ideas, compasses, or circles, referring to an easily projectible standard of utility.[60] Rejecting the Confucian idea of parents as a moral model as particular and unreliable, the driving idea of the Mohists was to find objective standards (Fa) for ethics and politics, as was done in any practical field, to order or govern society. These were primarily practical models rather than principles or rules.[61]

Mozi said, "Those in the world who perform tasks cannot do without models (fa) and standards. There is no one who can accomplish their task without models and standards. Even officers serving as generals or ministers, they all have models; even the hundred artisans performing their tasks, they too all have models. The hundred artisans make squares with the set square, circles with the compass, straight lines with the string, vertical lines with the plumb line, and flat surfaces with the level. Whether skilled artisans or unskilled artisans, all take these five as models. The skilled are able to conform to them. The unskilled, though unable to conform to them, by following them in performing their tasks still surpass what they can do by themselves. Thus the hundred artisans in performing their tasks all have models to measure by. Now, for the greatest to order (zhi, also 'govern') the world and those the next level down to order great states without models to measure by, this is to be less discriminating than the hundred artisans."[39]

Interschool examples include such uses as fa-tu (institutional measures), fa-yi (norms), fa-chi (constitutional regulations), fa shu (referring to Shen Buhai's administrative technique or method), li fa (norms of propriety), ch'an fa (methods of war) and ping-chun-chi-fa (norms for measurement).[51] Taking up Shen Buhai's method (Fa), besides universal rules, Han Fei used Fa for appointment, measurement, language and reward. Because Fa (standards) are necessary for articulating terms, Fa is presupposed in any application of punishment. Applied through rewards and punishments, Fa provided guidance for behaviour and performance, and governed advancement. Han Fei stressed measurement-like links between rewards and punishments and performance.[47]

The influence of the Mohists on "Legalist" thinkers like Han Fei and Li Si is likely strong.[62] Despite the framing of Han historians, the Legalists do not seem to think they are using Fa differently than anyone else. Theoretically, Han Fei's Fa exactly follows Mozi.[63] An example of excavated legal texts consists of twenty-five abstract model patterns guiding legal procedure, based on actual situations.[64]

Wei "Legalists"

Li Kui (403–387) wrote the Book of Law (Fajing, 法经) in the state of Wei, which was the basis for the codified laws of the Qin and Han dynasties, in 407 BC. His political agendas, as well as the Book of Law, had a deep influence on later thinkers such as Han Fei and Shang Yang, including the institution of meritocracy, and giving the state an active role in encouraging agriculture, purchasing grain to fill its granaries in years of good harvest to ease price fluctuations. The direct result of these pioneering reform measures was the dominance of Wei in the early decades of the Warring States era. He recommended Ximen Bao, credited as China's first hydraulic engineer, and Wu Qi as a military commander when Wu Qi sought asylum in Wei.[65][66]

Widely regarded as China's first great general, the Wu-tzu text attributed to Wu Qi (440-381 BC), seriously considering "all aspects of war and battle preparation", has long been valued as one of the "basic foundations of Chinese Military thought."[67] Passages from the Huainanzi suggest that Wu Qi "tried to implement typically Legalist reforms" in Wei.[68] His "impressive administrative contributions" are often ranked with Lord Shang, who served as a household tutor four decades after Wu left.[67]

Primary figures

Shang Yang and "Legalism"

Hailing from Wei, as Prime Minister of the State of Qin from 360-338 Shang Yang engaged in a "comprehensive plan to eliminate the hereditary aristocracy", abolishing the old fixed landholding system (Fengjian) and direct primogeniture, making it possible for the people "to sell and buy" farmland, encouraging the peasants of other states to come to Qin. Shang Yang emphasized law (fa) as the most important device for upholding the power of the state. He insisted that it be made known and applied equally to all, posting it on pillars erected in the new capital. In 350, along with the creation of the new capital, a portion of Qin was divided into thirty-one counties, each "administered by a (presumably centrally appointed) magistrate". This was a "significant move toward centralizing Ch'in administrative power" and correspondingly reduced the power of hereditary landholders.[69][70][71]

The Book of Lord Shang, drawing boundaries between private factions and the central, royal state, took up the cause of meritocratic appointment, stating "Favoring ones relatives is tantamount to using self-interest as one's way, whereas that which is equal and just prevents selfishness from proceeding." The Han Feizi credits Shang Yang with the theory of ding fa (fixing the standards) and yi min (treating the people as one),[72] and defines the Fa ("Standards") of Shang Yang in the following way: "'Standards' means that ordinances and commands are manifest in the administrative bureaux; laws and punishments are certain in the people's minds; rewards are generated for those who are careful about standards; and penalties accrue to those who defy commands. These are what subjects take as their preceptor. If the lord is without technique, then he will be beclouded above; if subjects are without standards, they will be disorderly below."[73]

Most Han works identify Shang Yang with penal law.[74] The Book of Lord Shang's discussion of bureaucratic control is simplistic, chiefly advocating punishment and reward.[3] On the other hand, Sinologist Chad Hansen argues that Shang Yang's Fa (or that of Xun Kuang or Han Fei) does not change meaning from that of the Mohists. Rather, Shang Yang's idea was that penal codes should be reformed to have the same kind of objectivity, clarity and accessibility as the craft-linked instruments,[59][75] describing them as performance standards (Fa) backed up by incentives and disincentives.[3] Shang Yang was largely unconcerned with the organization of the bureaucracy apart from this.[74]

Nevertheless, the book addresses many administrative questions, one of the most important forcing the populace to attend solely to agriculture and recruiting labour from other states. As the first of his accomplishments, historiographer Sima Qian accounts Shang as having divided the populace into groups of five and ten, instituting a system of mutual responsibility[76] tying status entirely to service to the state. It rewarded office and rank for martial exploits.[77] The recommendation that farmers be allowed to buy office with grain was apparently only implemented much later, the first clear-cut instance in 243 BCE.[72]

Objectivity was a primary goal of Shang Yang, wanting to be rid as much as possible of the subjective element in public affairs. The greatest good was order. History meant that feeling was now replaced by rational thought, and private considerations by public, accompanied by properties, prohibitions and restraints. In-order to have prohibitions, it is necessary to have executioners, hence officials, and a supreme ruler whose orders they would obey, to surpass subjective feelings. Virtuous men are replaced by qualified officials, objectively measured by Fa. The ruler should rely neither on his nor his officials deliberations, but on the clarification of Fa. Everything should be done by Fa,[78][79] whose transparent system of standards will prevent any opportunities for corruption or abuse.[80]

Shang Yang deliberately produced equality of conditions amongst the ruled, a tight control of the economy, and encouraged total loyalty to the state, including censorship and reward for denunciation. From a western viewpoint it might be said that he sought to establish the supremacy of what some have termed positive law at the expense of customary or "natural" law. Law was what the sovereign commanded, and this meant absolutism, but it was an absolutism of law as impartial and impersonal. Shang Yang discouraged arbitrary tyranny or terror as destroying law.[81] Neither did he rely on any external apparatus of coercion, but upon the citizenry as manifesting the aims of the ruler. Publicly declared rules and regulations were to ensure order without effort on the part of the ruler - the ideal of wu-wei.[81]

Mark Edward Lewis once identified Shang Yang's reorganization of the military as responsible the orderly plan of roads and fields throughout north China. This might be far fetched, but Shang Yang was as much a military reformer as a legal one.[82] Much of "Legalism" was "principally the development of certain ideas" that lay behind his reforms, and it was these that lead to "Qin's ultimate conquest over the other states of Eastern Zhou China in 221BCE."[5][59]

Following the execution of Shang Yang by aristocratic interests, including the king himself, King Huiwen turned away from the central valley south to conquer Sichuan (Shu and Ba) in what Steven Sage calls a "visionary reorientation of thinking" toward material interests in Qin's bid for universal rule.[83]

Shen Buhai

The basic structure and operation of the traditional Chinese state is not Legalist as it is commonly understood. Creel called its philosophy administrative for lack of a better term, and considered it to have been founded by Shen Buhai(400 BC-337 BC), who likely played an "outstanding role in the creation of the traditional Chinese system of government". No text identifies Shen Buhai with penal law, some just the opposite.[84] Shen Buhai sought impersonal administrative "techniques" (Fa) or "method" (shu) for recruiting candidates to office,[85] Objective and rational principles had to be used to select talents, evaluate performance, and administer the state.[86]

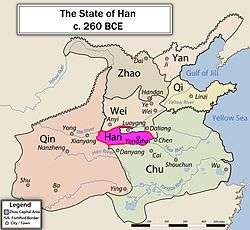

It is said that when Shen Buhai lived the officials of the state of Han were at cross-purposes, and did not know what practices to follow.[87] Born around 400BCE, Shen Buhai was Chancellor of Han from 351BCE to 337BCE.[88] What he appears to have realized is that the "methods for the control of a bureaucracy" could not be mixed with the survivals of feudal government, and that government "cannot be staffed merely by getting together a group of 'good men'", but rather must be men qualified in their jobs. He never mentions virtue.[89]

Shen Buhai's ruler had to make all crucial decisions himself. Ideally, he had the widest possible sovereignty, was intelligent (if not a sage) and had unlimited control of the bureaucracy. But compared with Shang Yang Shen refers to the ruler in abstract terms - he is simply the head of a bureaucracy.[90] Shen Buhai insisted that the ruler must be from fully informed on the state of his realm, but couldn't afford to get caught up in details and was advised to listen to no one - and does not, as Creel says, have the time to do so. The way to see and hear independently is method (fa), grouping particulars into categories - the ruler's eyes and hears will make him deaf and blind (unable to obtain accurate information).[91]

Shen Buhai believed that the ruler's most able ministers are his greatest danger,[92] and is convinced that it is impossible to make them loyal without techniques,[93] though unlike Shang Yang and Han Fei did not consider the relationship between ruler and minister antagonistic necessarily.[94] Shen Buhai's statement that those near him will feel affection, while the far will yearn for him,[95] stands in contrast to Han Fei, who considered the relationship between the ruler and ministers irreconcilable.[96]

Shu (technique)

Creel translates Shen's Fa as "method".[97] Shen's contemporaries often used the term Shu (technique) for it, and thus Feng Youlan called Shen Buhai the leader of the group [in the Legalist school] emphasizing Shu, or methods of government.[98][99] Shu may be considered the most crucial element in controlling a bureaucracy.[100] The History of the Han (Han shu) lists texts for Shu as devoted to "calculation techniques" and "techniques of the mind", and describes the Warring States period as a time when the shu arose because the complete tao had disappeared.[101] It is closely related to an earlier term for graphs;[102] in the Guanzi the artisan's shu is explicitly compared to that of the good ruler.[103] More specifically, though, Shen's doctrines, or Shu, are described as concerned almost exclusively with the selection of capable ministers, their performance, and the monopolization of power.[74]

Liu Xiang wrote that Shen Buhai advised the ruler of men use technique (shu) rather than punishment, relying on persuasion to supervise and hold responsible, though very strictly.[85][104] Shen Buhai's defines his method (fa) as "to scrutinize achievement and on that ground alone to give rewards, and to bestow office solely on the basis of ability".[105] Han Fei defines the technique of Shen Buhai more broadly as "to bestow offices corresponding to [people's] abilities; to hold achievement accountable to claim (xing-ming); to grasp the handles of life and death; and to supervise the abilities of the thronging ministers. This is what the lord of men wields." Han Fei criticizes Shen's philosophy as lacking laws, but insists that the ruler use his technique to recruit ministers, and conversely criticizes Shang Yang as lacking Shu.[106]

Creel notes that command of finance was generally held by the head of government from the beginning of the Zhou dynasty; an example of auditing dates to 800 B.C., and the practice of annual accounting solidified by the Warring States Period and budgeting by the first century B.C.[102] He believed that Shu originally had the sense of numbers, with implicit roots in statistical or categorizing methods, using record keeping in financial management as a numerical measure of accomplishment.[107][108] Shen Buhai does this using the mechanical or operational decision making of the Mohist's fa (measurement standards).[109]

Another example example of Shu is Chuan-shu, or "political maneuvering". The concept of Ch'uan, or "weighing" figures in "Legalist" writings from very early times. It also figures in Confucian writings as at the heart of moral action, including in the Mencius and the Doctrine of the Mean. Weighing is contrasted with "the standard". Life and history often necessitate adjustments in human behavior, which must suit what is called for at a particular time. It always involves human judgement. A judge that has to rely on his subjective wisdom, in the form of judicious weighing, relies on Ch'uan. The Confucian Zhu Xi, who was notably not a restorationist, emphasized expedients as making up for incomplete standards or methods.[110]

Wu-Wei

Shen Buhai advises the ruler to keep his own counsel, hide his motivations and conceal his tracks.[111] His ruler relies on method (or "techniques") rather than punishment to supervise the government, and must not do the actual business of government himself.[112] Relying on techniques conceals the ruler's intentions, likes and dislikes, skills and opinions. Not acting himself, he can avoid being manipulated.[113] This Wu-Wei (or nonaction) might be said to be the political theory of the Legalists, if not becoming their general term for political strategy, playing a "crucial role in the promotion of the autocratic tradition of the Chinese polity". Nonaction ensures the power of the ruler and the stability of the polity.[114]

Shen Buhai used the term wu-wei to mean that the ruler, though vigilant, should not interfere with the duties of his ministers.[113] The only other book to use the term in this manner is the Tao Te Ching, and since it was composed later sinologist Herrlee G. Creel argued that it may therefore be assumed that Shen influenced the Tao Te Ching.[113]

Shen Buhai's ruler plays no active role in governmental functions. He should not use his talent even if he has it.[115] Not using his own skills, he is better able to secure the services of capable functionaries. He attempts to abstain from any arbitrary interference or subjective considerations - making an official's words his own responsibility.[116] Creel argued that this leaves the ruler free to supervise the government without interfering, which also maintains his perspective.[117] Seeing and hearing independently, he is able to make decisions independently, and is, Shen says, able to rule the world thereby.[118]

The Han Feizi's commentary on the Tao Te Ching similarly asserts that perspectiveless knowledge - an absolute point of view - is possible, though the chapter may have been one of his earlier writings.[119] Another chapter reads:

[The bright ruler] is undifferentiated and quiescent in waiting, causing names to define themselves and affairs to fix themselves. If he is undifferentiated then he can understand when actuality is pure, and if he is quiescent then he can understand when movement is correct.[120][121]

Many later texts, for instance in Huang-Lao, use similar images to describe the quiescent attitude of the ruler.[120] The Huainanzi, an influential, syncretic treatise from the early Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C.– 9 A.D.) defines wu-wei as follows: “What is meant […] by wu-wei is that no personal prejudice [private or public will,] interferes with the universal Tao [the laws of things], and that no desires and obsessions lead the true course […] astray. Reason must guide action in order that power may be exercised according to the intrinsic properties and natural trends of things.”[122]

Ming-shih (appointment)

In the Han Dynasty secretaries of government who had charge of the records of decisions in criminal matters were called Xing-Ming, which Sima Qian and Liu Xiang attributed to the doctrine of Shen Buhai.[116][123] It functions through binding declarations, like a legal contract. Verbally committing oneself, a candidate is allotted a job, indebting him to the ruler.[124] It is relatable with the Confucian tradition in which a promise or undertaking, especially in relation to a government aim, entails punishment or reward.[125] We have no basis to suppose that Shen advocated the doctrine the doctrine of rewards and punishments,[126] but Han Fei did.

Han Fei's Fa was notoriously focused on Xing-Ming.[127] The more philosophically common equivalent Shen Buhai uses, ming-shih (name and reality),[123][128] links what would become a central concept of "Legalist" thought, the "Legalist doctrine of names", with the name and reality (ming shih) debates of the school of names.[129] Such discussions are also prominent in the Han Feizi.[130]

Sima Qian and Liu Xiang defined Xing-Ming as holding "actual outcome accountable to (the) claim (of each official)".[116][131] Rather than having to look for "good" men, Xing-Ming can simply seek the right man for a particular post, though doing so implies a total organizational knowledge of the regime.[132] Noting all the details of a claim and then attempting to objectively compare them with his achievements, through passive mindfulness (the "method of yin") the ruler neither adds to nor detracts from anything, giving names (titles/offices) on the basis of form (ming).[116]

Ming sometimes has the sense of speech - so as to compare the statements of an aspiring office with the reality of his actions - or reputation, again compared with real conduct.[133] Assessing the accountability of his words to his deeds,[134] the ruler tests abilities, and attempts to "determine rewards and punishments in accordance with a subject's true merit",[135] ensuring that only those competent would be admitted to, or remain in office.[134] It is said that using names (ming) to demand realities (shih) exalts superiors and curbs inferiors,[136] provides a check on the discharge of duties, and naturally results in emphasizing the high position of superiors, compelling subordinates to act in the manner of the latter.[87]

A stele set up by Qin Shi Huang memorializes him as a sage that established Xing-Ming, and Emperor Wen of Sui is recorded as having withdrawn his favour from the Confucians, giving it to "the group advocating Xing-Ming and authoritarian government".[137] As protégé of a Han Dynasty Commandant of Justice that had studied under Li Si, Jia Yi was also student of Shen Pu-hai.[138] The Emperor Xuan of Han was said by Liu Xiang to have been fond of reading Shen Buhai, using Xing-Ming to control his subordinates and devoting much time to legal cases.[139]

As early as the Eastern Han its full and original meaning would be forgotten,[99] and would come to be regarded as being in opposition to Confucians. Yet the writings of Tung-Cung-shu discuss personnel testing and control in a manner sometimes hardly distinguishable from the Han Feizi. He also uses the term ming-shih, and dissuades against reliance upon punishments. As Confucianism ascended the term disappeared.[140]

In Chinese Thought: An Introduction S.Y. Hsieh suggests a set of assumptions underlying the concept of (xing-ming).

- That when a large group of people are living together, it is necessary to have some form of government.

- The government has to be responsible for a wide range of things, to allow them to live together peacefully.

- The government does not consists of one person only, but a group.

- One is a leader that issues orders to other members, namely officials, and assigns responsibilities to them.

- To do this, the leader must know the exact nature of the responsibilities, as well as the capabilities of the officials.

- Responsibilities, symbolized by a title, should correspond closely with capabilities, demonstrated by performance.

- Correspondence measures success in solving problems, and also controls the officials. When there is a match, the leader should award the officials.

- It is necessary to recruit from the whole population. Bureaucratic government marks the end of feudal government.[88]

Shen Dao

Not many passages of Shen Buhai remain extant, but Shen Dao uses Fa in the same sense, using impersonal administration to determine rewards and punishments in accordance with a subject’s "true" merit. He also uses law. Shen Dao was referred to by the Confucian Xun Kuang as "beclouded by fa".

The reason why those who apportion horses use ce-lots, and those who apportion fields use gou-lots, is not that they take ce and gou-lots to be superior to human wisdom, but that one may eliminate private interest and stop resentment by these means. Thus it is said: 'When the great lord relies on fa and does not act personally, affairs are judged in accordance with fa.' The benefit of fa is that each person meets his reward or punishment according to his due, and there are no further expectations of the lord. Thus resentment does not arise and superiors and inferiors are in harmony.If the lord of men abandons fa and governs with his own person, then penalties and rewards, seizures and grants, will all emerge from the lord's mind. If this is the case, then those who receive rewards, even if these are commensurate, will ceaselessly expect more; those who receive punishment, even if these are commensurate, will endlessly expect more lenient treatment. If the lord of men abandons fa and decides between lenient and harsh treatment on the basis of his own mind, then people will be rewarded differently for the same merit and punished differently for the same fault. Resentment arises from this.[141]

Compared with the egoist Yang Chu, the "Legalist" Shen Dao is characterized by the Zhuangzhi as impartial and lacking selfishness, his great way embracing all things.[142] Wang Fuzhi speculated that the chapter "Essay on Seeing Things as Equal" was actually written by Shen Dao.[143] Upholding measurements and capacities, Shen Dao links laws to the notion of impartial objectivity associated with universal interest, reframing the language of the old ritual order to fit a universal, imperial and highly bureaucratized state.[144]

Shen Dao contrasts personal opinions with the merit of the objective standard, fa, as preventing personal judgements or opinions from being exercised; personal opinions destroy the law (Fa). Shen Dao's ruler "does not show favoritism toward a single person."[144] He cautions the ruler against relying on his own personal judgment.[145] His book, the Shenzi states "balances and scales are the means by which universal measures are established; books and contracts are the means by which universal trust is established; lengths and volumes are the means by which universal criteria are established; legal policies and ritual compendia are the means by which public justice is established. Wherever the universal good (gong) is established, partial interests are abandoned...

When an enlightened ruler establishes [gong] ("duke" or "public interest"), [private] desires do not oppose the correct timing [of things], favoritism does not violate the law, nobility does not trump the rules, salary does not exceed [that which is due] one's position, a [single] officer does not occupy multiple offices, and a [single] craftsman does not take up multiple lines of work... [Such a ruler] neither overworked his heart-mind with knowledge nor exhausted himself with self-interest (si), but, rather, depended on laws and methods for settling matters of order and disorder, rewards and punishments for deciding on matters of right and wrong, and weights and balances for resolving issues of heavy or light...[144]

Power

Generally speaking, the "Legalists" understood that power resides in social and political institutions.[146] Shen Dao largely focused on statecraft.[147] His theory on power may have been borrowed from the Book of Lord Shang.[148] Xun Kuang never references Shen Dao in relation to power, focusing on his theories on Fa.[149] He is remembered for his theories on power because Han Fei references him in this capacity for his similar arguments.[150] Used in many areas of Chinese thought, Shih probably originated in the military field.[151] Sunzi would go on to incorporate Taoist philosophy of inacation and impartiality, and Legalist punishment and rewards as systematic measures of organization, recalling Han Fei's concepts of power (shih) and tactics (shu).[152] Diplomats relied on concepts of situational advantage and opportunity, as well as secrecy (shu) long before "Legalist" concepts of sovereignty and law, and were used by kings wishing to free themselves from the aristocrats.[153]

For Shen Dao, “Power” (Shih) refers to the ability to compel compliance; it requires no support from the subjects, though it does not preclude this.[150] Shen Dao's theory on power states that morality together with intellectual capability are insufficient to rule,[150] but position of authority is enough to attain influence and subdue the worthy.[145] Talent also cannot be displayed without power.[154] Shen Dao said: “The flying dragon rides on the clouds and the rising serpent wanders in the mists. But when the clouds disperse and the mists clear up, the dragon and the serpent become the same as the earthworm and the large winged black ant because they have lost what they ride."[150]

Leadership is not a function of ability or merit, but is given by some a process, such as giving a leader to a group.[155] "The ruler of a state is enthroned for the sake of the state; the state is not established for the sake of the prince. Officials are installed for the sake of their offices; offices are not established for the sake of officials...[144][156] Its (Shih's) merit is that it prevents people from fighting each other; political authority is justified and essential on this basis.[157] For Han Fei, Fa (standards) itself is justified as preventing disputes in language or knowledge.[158]

Shen Dao does not completely disregard personal capability; he states that a ruler should give jobs using his "wisdom". He also considered moral capability useful in terms of authority. If the ruler is inferior but his command is practised, it is because he is able to get support from people.[150] As interpreted by Han Fei, Shen Dao is remembered for his slogan, "abandon knowledge, discard self", developing the concept of the natural dao, or the actual course of events, to undermine conventional appeals to systems of guidance. There are no standards apart from the influence of social leadership. These have no special value. An assertion of knowledge implies that one has the correct dao.[159] Shen Dao said that "'Law does not come down from Heaven, nor out of the Earth; it merely emerges in human society, and accords with people's minds." He considered a bad law better than no law at all.[160]

Han Fei criticizes this as insufficient; power should amassed through laws (fa),[161] and government by moral persuasion and government by power (shih) are mutually incompatible.[150] Neither the ruler's authority nor the application of standards should depend on the ruler's personal qualities or cultivation.[158] In-order to actually influence, manipulate or control others in an organization and attain organizational goals it is necessary to utilize tactics (shu), regulation (fa), and rewards and punishment - the "two handles".[162][163] The latter is similar to the Behaviorists,[162] and determines social positions - the right to appoint and dismiss - and should never be relegated.[164] If this is delegated and people are appointed on the basis of reputation or worldy knowledge, then rivals will emerge and the ruler's power will fall to opinion and cliques (the ministers). Standards are his only protection.[165] Han Fei does stress that the leader has to occupy a position of substantial power before he is able to use these, or command followers. Competence or moral standing do not allow command.[154]

Han Fei

Besides rules, Han Fei frequently philosophized the use of Fa for appointment, measurement, language and reward,[75] as in the following: "An enlightened ruler employs fa to pick his men; he does not select them himself. He employs Fa to weigh their merit; he does not fathom it himself. Thus ability cannot be obscured nor failure prettified. If those who are [falsely] glorified cannot advance, and likewise those who are maligned cannot be set back, then there will be clear distinctions between lord and subject, and order will be easily [attained]. Thus the ruler can only use fa."[166]

Han Fei intended his Dao (way of government) to be both objective and publicly projectable,[167] arguing that disastrous results will occur if the ruler acts on arbitrary ad-hoc decisions, such as those based on relationships or morality - the political tradition of the Confucians. Neither can he act on a case-by-case basis, and so must establish an overarching system, acting through legal codes (Fa). He says: "If one abandons law and techniques and [attempts to] order the state based on one’s own ideas, in this way even Yao could not order a single state. If one discards the compass, carpenter’s square and measures (Fa) and acts based on one’s own rash ideas, even Xi Zhong could not complete a single wheel... If a mediocre ruler abides by laws and techniques, or if a clumsy carpenter abides by the compass, square, measurements, then in ten thousand tries, he never will go wrong. If the lord can... abide by what the mediocre and clumsy cannot get wrong in ten thousand tries, then the people’s power will be used to the utmost, and [the ruler’s] achievements and fame will be established."

One of Han Fei's primary notions, zhi emphasizes straightness and the notion of an unbiased heart, saying "What we mean by zi is that, in doing one's duty, to act always impartially and honestly with an unbiased heart." This notion of honest conduct with unbiased intention underlies Qin and Han penal law. Biased judgement, or purposefully handing down judgements in which the punishment is not appropriate to the crime, is defined as a serious crime called buzhi ("not straight"). It is clearly distinguished from mistakes in judging or punishing a crime. Buzhi officials were sent to build the great wall, or exiled to the frontier. A son might be considered crooked for reporting his father, as trying to gain a reputation of honesty at the expense of his father's.[168]

Han Fei insists on the perfect congruence between words and deeds. Fitting the name is more important than results.[169] The completion, achievement, or result of a job is it's assumption of a fixed form (xing), which can then be used as a standard against the original claim (ming).[170] Verbally committing himself, the candidate is allotted a job,[171] and rewarded or punished according to whether the results fit the task entrusted by their word, which a real minister fulfils.[172] A large claim but a small achievement is inappropriate to the original verbal undertaking, while a larger achievement takes credit by overstepping the bounds of office.[173]

Han Fei's "brilliant ruler" "orders names to name themselves and affairs to settle themselves."[173]

"If the ruler wishes to bring an end to treachery then he examines into the congruence of the congruence of hsing (form/standard) and claim. This means to ascertain if words differ from the job. A minister sets forth his words and on the basis of his words the ruler assigns him a job. Then the ruler holds the minister accountable for the achievement which is based solely on his job. If the achievement fits his job, and the job fits his words, then he is rewarded. If the achievement does not fit his jobs and the job does not fit his words, then he will be punished.[174]

Han Fei emphasizes that through this system, initially developed by Shen Buhai, uniformity of language could be developed,[175] functions could be strictly defined to prevent conflict and corruption, and objective rules (Fa) impervious to divergent interpretation could be established, judged solely by their effectiveness.[176] By narrowing down the options to exactly one, discussions on the "right way of government" could be eliminated. Whatever the situation brings is the correct Dao.[177]

The "Two Handles"

Han Fei's administrative theory is based on the premise of self-interest.[178] Linking the "public" sphere with justice and objective standards, for Han Fei, the private and public had always opposed each other.[144] Han Fei presents Fa as contrasting with private distortions and behaviour. Fa is never merely the ruler's desires.[179] Law (Fa) is not partial to the noble, does not exclude ministers, and does not discriminate against the common people.[180]

Han Fei calls the Confucian teaching on love and compassion for the people the "stupid teaching" and "muddle-headed chatter",[181] the emphasis on benevolence an "aristocratic and elitist ideal" demanding that "all ordinary people of the time be like Confucius' disciples", and argues against moral considerations, which, as a product of reason, are "particular and fallible". Li, or Confucian customs, and rule by example are simply too ineffective.[182][183] The prince must make use of fa (law), surround himself with an aura of wei (majesty) and shi (authority, power, influence),[182][184] and make use of the art (shu) of statecraft. The ruler who follows Tao moves away from benevolence and righteousness, and discards reason and ability, subduing the people by law. Only an absolute ruler can restore the world.[182]

The Legalists' view of the people as selfish is not exceptional, but are distinct from the Confucians in dismissing the possibility of reforming the elite, that being the ruler and ministers, or driving them by moral commitment. Every member of the elite pursues his own interests, and this is the source of thinkers "great concern with regard to the ongoing and irresolvable power struggle between the ruler and the members of his entourage." It is because of this that Han Fei and other "Legalists" "insist on the priority of impersonal norms and regulations in dealing with the ruler-minister relations".[96] The target of Han Fei's fa (method, standards) in particular are the scholarly bureaucracy and ambitious advisers - the Confucians[185] Long sections of Han Fei's writings provide example of how ministers undermined various rules, and focus on how the ruler can protect himself against treacherous ministers, emphatically emphasizing their mutually different interests.[186]

The Han Feizi may have been as a handbook for statecraft for his cousin, the King of Han.[187] Devoting the entirety of Chapter 14, "How to Love the Ministers", to "persuading the ruler to be ruthless to his ministers", Han Fei's enlightened ruler strikes terror into his ministers by doing nothing. The qualities of a ruler, his "mental power, moral excellence and physical prowess" are irrelevant. He discards his private reason and morality, and shows no personal feelings. What is important is his method of government. Law requires no perfection on the part of the ruler.

Han advised the ruler to control his ministers using the "two handles" of punishment and favour. As a matter of illustration, if the "keeper of the hat" lays a robe on the sleeping Emperor, he has to be put to death for overstepping his office, while the "keeper of the robe" has to be put to death for failing to do his duty.[23] The philosophy of the "Two Handles" likens the ruler to the tiger or leopard, which "overpowers other animals by its sharp teeth and claws." Without them he is like any other man; his existence depends upon them. To "avoid any possibility of usurpation by his ministers", power and the "handles of the law" must "not be shared or divided", concentrating them in the ruler exclusively.

In practice, this means that the ruler must be isolated from his ministers. The elevation of ministers endangers the ruler, with which he must be kept strictly apart. Punishment confirms his sovereignty; law eliminates anyone who oversteps his boundary, regardless of intention. Law "aims at abolishing the selfish element in man and the maintenance of public order", making the people responsible for their actions.[188]

Xuezhi Guo contrasts the Confucian "Humane ruler" with the "Legalists" as "intending to create a truly 'enlightened ruler'". He quotes Benjamin I. Schwartz as describing the features of a truly "Legalist" "enlightened ruler":[189]

"He must be anything but an arbitrary despot if one means by a despot a tyrant who follows all his impulses, whims and passions. Once the systems which maintain the entire structure are in place, he must not interfere with their operation. He may use the entire system as a means to the achievement of his national and international ambitions, but to do so he must not disrupt its impersonal workings. He must at all times be able to maintain an iron wall between his private life and public role. Concubines, friends, flatterers and charismatic saints must have no influence whatsoever on the course of policy, and he must never relax his suspicions of the motives of those who surround him."[189][190]

Han Fei's rare appeal (among "Legalists") to the use of scholars (law and method specialists) makes him comparable to the Confucians, in that sense. Contrary to Shen Buhai and his own rhetoric, Han Fei insists that loyal ministers (like Guan Zhong, Shang Yang, and Wu Qi) exist, and upon their elevation with maximum authority. The ruler cannot inspect all officials himself, and must rely on the decentralized (but faithful) application of laws and methods (fa). This scheme nonetheless effectively neutralizes the ruler, reducing his role to the maintenance of the system of reward and punishments, determined according to impartial methods and enacted by specialists expected to protect him through their usage thereof.[191][192]

As easily as mediocre carpenters can draw circles by employing a compass, anyone can employ the system Han Fei envisions.[193] The enlightened ruler restricts his desires and refrains from displays of personal ability or input in policy. The ruler that relies on his abilities is the worst ruler; capability is not dismissed, but the ability to use talent will allow the ruler greater power if he can utilize others with the given expertise.[194] Laws and regulations allow him to utilize his power to the utmost. Adhering unwaveringly to legal and institutional arrangements, the average monarch is numinous.[195] A.C. Graham writes,

(Han Fei's) ruler, empty of thoughts, desires, partialities of his own, concerned with nothing in the situation but the 'facts', selects his ministers by objectively comparing their abilities with the demands of the offices. Inactive, doing nothing, he awaits their proposals, compares the project with the results, and rewards or punishes. His own knowledge, ability, moral worth, warrior spirit, such as they may be, are wholly irrelevant; he simply performs his function in the impersonal mechanism of state."[196]

A component in a machine, his functions could be "performed by an elementary computer". The ruler simply checks "shapes" against "names" and dispenses rewards and punishments accordingly.[197] Submerged by the system he supposedly runs, the alleged despot disappears from the scene.[198]\

Imperial China

Qin dynasty

The intrastate realpolitik would end up devouring the philosophers themselves. Holding that if punishments were heavy and the law equally applied, neither the powerful nor the weak would be able to escape consequences, Shang Yang advocated the state's right to punish even the ruler's tutor, and ran afoul of the future King Huiwen of Qin (c. 338–311 BC). Whereas at one point, Shang Yang had the power to exile his opponents (and, thus, eviscerate individual criticism) to border regions of the state, he was captured by a law he had introduced and died being torn into pieces by chariots. Similarly, Han Fei would end up being poisoned by his envious former classmate Li Si, who in turn would be killed (under the law he had introduced) by the aggressive and violent Second Qin Emperor that he had helped to take the thrones.

However, guided by the "Legalists" thought, the First Qin Emperor Qin Shi Huang conquered and unified the China's warring states into thirty-six administrative provinces, under what is commonly thought of as the first Chinese Empire, the Qin dynasty. His Prime Minister Li Si unified the laws, governmental ordinances, and weights and measures, and standardized chariots, carts, and the characters used in writing. He created a government based solely on merit. He relaxed the draconian punishments inherited from Shang Yang and reduced the taxes.[199] The Warring States period Confucian thinker Xun Zi was considered as having been influenced by and nourishing Legalist ideas, influencing (Li Si and Han Fei).[200]

The Qin document "On the Way of Being an Official" proclaims the ideal of the official as a responsive conduit, transmitting the facts of his locale to the court, and its orders, without interposing his own will or ideas. It charges the official to obey his superiors, limit his desires, and to build roads to smooth the transmitting of directives from the center without modification. It praises loyalty, absence of bias, deference, and the appraisal of facts.[26]

Han Dynasty

With the coming of the Han dynasty, the reputation of Legalism suffered from its association with the former Qin dynasty. Sima Tan, though the hailing the Fa "school" for "honoring rulers and derogating subjects, and clearly distinguishing offices so that no one can overstep [his responsibilities]", criticized the Legalist approach as "a one-time policy that could not be constantly applied."[201]

The syncretic Han Dynasty text, the Huainanzi writes that "On behalf of the Ch'in, Lord Shang instituted the mutual guarantee laws, and the hundred surnames were resentful. On behalf of Ch'u, Wu Ch'i issued order to reduce the nobility and their emoluments, and the meritorious ministers revolted. Lord Shang, in establishing laws, and Wu Ch'i, in employing the army, were the best in the world. But Lord Shang's laws [eventually] caused the loss of Ch'in for he was perspicacious about the traces of the brush and knife, but did not know the foundation of order and disorder. Wu Ch'i, on account of the military, weakened Ch'u. He was well practiced in such military affairs as deploying formations, but did not know the balance of authority involved in court warfare."[68]

Despite this, the administration and political theory developed during the formative Warring States period would still influence every dynasty thereafter, as well as the Confucian philosophy that underlay Chinese political and juridical institutions.[202] The influence of Legalism on Han Confucianism is very apparent, adopting Han Fei's emphasis of a supreme ruler and authoritarian system rather than Mencius's devaluation thereof, or Xun Kuang's emphasis on the Tao.[203]

Shen Buhai's book appears to have been widely studied in the beginning of the Han era,[111] and the concept attributed to him, Shu (techniques) would become a new structure by which some thinkers explained virtue. The writings of early Han scholar Jia Yi's simply blamed the fall of the dynasty on the education of the second emperor.[204] Jia Yi's (200-168 AD) Hsin-shu, undoubtedly influenced by the Legalists, describes Shu as a particular method of applying the Tao, or virtue, bringing together Confucian and Taoist discourses. He uses the imagery of the Zhuangzhi of the knife and hatchet as examples of skillful technique in both virtue and force, saying "benevolence, righteousness, kindness and generosity are the ruler's sharp knife. Power, purchase, law and regulation are his axe and hatchet".[205]

Shen Buhai never attempts to articulate natural or ethical foundations for his Fa (administrative method), nor does he provide any metaphysical grounds for his method of appointment (later termed "xing-ming"),[206] but later texts do. The Huang-Lao work Boshu grounds fa and xing-ming in the Taoist Dao.[207] Hsu Kai (920-974 AD) calls Shu a branch in, or components of, the great Tao, likening it to the spokes on a wheel. He defines it as "that by which one regulates the world of things; the algorithms of movement and stillness." Mastery of techniques was a necessary element of sagehood.[101]

In the Discourses on Salt and Iron's the Lord Grand Secretary uses Shang Yang in his argument against the dispersion of the people, stating that "a Sage cannot order things as he wishes in an age of anarchy". He recalls Lord Shang's chancellery as firm in establishing laws and creating orderly government and education, resulting in profit and victory in every battle.[208] Although Confucianism was promoted by the new emperors, the government continued to be run by Legalists. Emperor Wu of Han (140–87 BC) barred Legalist scholars from official positions and established a university for the study of the Confucian classics,[209] but his policies and his most trusted advisers were Legalist.[210] Michael Loewe called the reign of Emperor Wu the "high point" of Modernist (classically justified Legalist) policies, looking back to "adapt ideas from the pre-Han period."[211] An official ideology cloaking Legalist practice with Confucian rhetoric would endure throughout the imperial period, a tradition commonly described as wàirú nèifǎ (Chinese: 外儒内法; literally: "outside Confucian, inside Legalist").[212]

During the decay of the Han Dynasty, many scholars again took up an interest in "Legalism", Taoism and even Mohism.[213] Han sources "came to treat Legalism as an alternative to the methods of the Classicists."[214] It became commonplace to adapt Legalist theories to the Han state by justifying them using the classics, or combining them with the notion of the "way" or "pattern of the cosmos" ("The Way gave birth to law" Huangdi Sijing). Some scholars "mourne" the lack of pure examples of Daoism, Confucianism and Legalism in the Han dynasty more generally.[215] Usually referring to Warring States period philosophers, during the Han Fa-jia would be used for others disliked by the Confucian orthodoxy, like the otherwise Confucianistic reformers Guan Zhong and Xunzi,[216] and the Huang-Lao Taoists.[217]

The Records of the Three Kingdoms describes Cao Cao as a hero who "devised and implemented strategies, lorded the world over, wielded skillfully the law and political technique of Shen Buhai and Shang Yang, and unified the ingenious strategies of Han Fei."[218]

Zhang Juzheng

In 1572 Zhang Juzheng, a legalistic, prime-minister like figure of the Ming Dynasty, had the young emperor of the time issue a warning edict against China's bureaucracy with the reference that they had abandoned the public interest for their own private interests. It reads: "From now on, you will be pure in your hearts and scrupulous in your work. You will not harbor private designs and deceive your sovereign... You will not complicate debates and disconcert the government." It suggests that good government will prevail as long as top ministers were resolute in administration of the empire and minor officials were selflessly devoted to the public good. It is said that the officials became "very guarded and circumspect" following its release. His "On Equalizing Taxes and Succoring the People" postulated that the partiality of local officials toward powerful local interests was responsible for abuses in tax collection, hurting both the common people and the Ming state.[219]

Zhang Juzheng wrote that "it is not difficult to erect laws, but it is difficult to see they are enforced." His Regulation for Evaluating Achievements (kao cheng fa) assigned time limits for following government directives and made officials responsible for any lapses, enabling Zhang to monitor bureaucratic efficiency and direct a more centralized administration. That the rules were not ignored are a testament to his basic success.[220]

Modern

The Communists would use Legalism in their criticism of Confucianism, describing the conflict between the two as class struggle.[221] Fazhi, another historical term for "Legalism", would be used to refer to both socialist legality and Western rule of law. Still constrated with renzhi (or rule of persons), most Chinese wanted to see it implemented in China.[222] Rule of law again gained prominent attention in the 1970s after the Cultural Revolution, in Deng Xiaoping's platform for modernization.

Two decades of reform, Russia's collapse and a financial crisis in the 1990s only served to increase its importance, and the 1999 constitution was amended to "provide for the establishment of a socialist rule-of-law state", aimed at increasing professionalism in the justice system. Signs and flyers urged citizens to uphold the rule of law.[223] In the following years figures like Pan Wei, a prominent Beijing political scientist, would advocate a consultative rule of law with a redefined role for the party and limited freedoms for speech, press, assembly and association.[224]

As Communist ideology plays a less central role in the lives of the masses in the People's Republic of China, top political leaders of the Communist Party of the People's Republic of China such as Xi Jinping continue the rehabilitation of figures like Han Fei into the mainstream of Chinese thought alongside Confucianism, both of which Xi sees as relevant.[225] Han Fei gained new prominence with favourable citations. One sentence of Han Fei's that Xi quoted appeared thousands of times in official Chinese media at the local, provincial, and national levels.[226]

As "Realists"

Some early modern scholars like Arthur Waley used the term "Realist", believing that said "Realists", rejecting all appeals to tradition and the supernatural, held that law should replace morality.[227][228][229] The aspect of "Legalism" focusing on appointment and performance measurements, Ming-shih/Xing-Ming, derives of Chinese correlative thought. It's immanent cosmos and ontology is made more of parts than particular entities, and unlike that of Realists of the west, precludes transcendentalism and universals.[230] Waley contrasts what he terms the Realists with other the schools as largely ignoring the individual, holding that the object of any society is to dominate other societies,[231] and A.F.P. Hulsewé writes "(Shang Yang and Han Fei) were not so interested in the contents of the laws as in their use as a political tool... the predominantly penal laws and a system of rewards were the two 'handles'".[232]

On rare occasion Han Fei lauds such qualities as benevolence and proper social norms, nonmorally.[182] One more recent Chinese scholar argued that "Han’s legal vision is informed by an expansive view of not only ethics but also justice... defined as a moral choice between personal interests and public obligations..."[233] But more generally Han Fei "eschewed ethics in favour of strategy."[234] The "Legalists" goal was to teach the ruler techniques to survive in a competitive world[234][235] through administrative reform - strengthening the central government, increasing food production, enforcing military training, or replacing the aristocracy with a bureaucracy.[235] Han Fei is not interested in questions like legitimacy, and does not justify "Legalism" apart from references to the Dao, but does hold that the populace fares better under a system of law than a Confucian system.[236]

Liang Zhiping theorized that law emerged initially in China, namely, as an instrument by which a single clan exercised control over rival clans.[237] In the earlier Spring and Autumn period, a Qin king is recorded as having memorialized penalty as a ritual function benefiting the people, saying "I am the little son: respectfully, respectfully I obey and adhere to the shining virtuous power, brightly spread the clear punishments, gravely and reverentially perform my sacrifices to receive manifold blessings. I regulate and harmonize myriad people, gravely from early morning to evening, valorous, valorous, awesome, awesome – the myriad clans are truly disciplined! I completely shield the hundred nobles and the hereditary officers. Staunch, staunch in my civilizing and martial [power], I calm and silence those who do not come to the court [audience]. I mollify and order the hundred states to have them strictly serve the Qin."[238]

Angus Charles Graham sketched the fundamentals of an "amoral science" largely on the basis of the Han Feizi, consisting of "adapting institutions to changing situations and overruling precedent where necessary; concentrating power in the hands of the ruler; and, above all, maintaining control of the factious bureaucracy."[239] More recently, Ross Terrill wrote that "Chinese Legalism is as Western as Thomas Hobbes, as modern as Hu Jintao. It speaks the universal and timeless language of law and order. The past does not matter, state power is to be maximized, politics has nothing to do with morality, intellectual endeavour is suspect, violence is indispensable, and little is to be expected rom the rank and file except and appreciation of force." He calls "Legalism" the "iron scaffolding of the Chinese Empire", but emphasizes the marriage between Legalism and Confucianism.[240]

Chinese law expert Peerenboom compared Han Fei against the accepted standards of legal positivism and concluded that he is a legal positivist. Establishing the ruler as the ultimate authority over the law, he also “shares the belief that morality and the law need not coincide.”[241] The comparison is controversial, however.

References

- ↑ Paul R. Goldin, Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism. p.4 http://www.academia.edu/24999390/Persistent_Misconceptions_about_Chinese_Legalism_

- ↑ Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Introduction. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/chinese-legalism/

- 1 2 3 4 Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, p.59 The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy https://books.google.com/books?id=I0iMBtaSlHYC&pg=PA59

- ↑ Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), 2. Philosophical Foundations http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/chinese-legalism/

- 1 2 http://www.indiana.edu/~p374/Legalism.pdf LEGALISM AND HUANG-LAO THOUGHT. Indiana University, Early Chinese Thought R. Eno.

- ↑ Paul R. Goldin, Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism. p.15 http://www.academia.edu/24999390/Persistent_Misconceptions_about_Chinese_Legalism_

- ↑ Chad Hansen, 1992 p.344 A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA344

- ↑ Herrlee G. Creel, 1974 p.120. Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1.

- Zhengyuan Fu, 1996 China's Legalists p.7

- ↑ Ewan Ferlie, Laurence E. Lynn, Christopher Pollitt 2005 p.30, The Oxford Handbook of Public Management

- Herrlee G. Creel, 1974 p.119. Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1.

- Creel, The Origins of Statecraft in China, I, The Western Chou Empire, Chicago, pp.9-27

- Otto B. Van der Sprenkel, 'Max Weber on China', in History and Theory3(1964), 357.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet 1982 p.92. A History of Chinese Civilization. https://books.google.com/books?id=jqb7L-pKCV8C&pg=PA92

- Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Epilogue. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-legalism/#EpiLegChiHis

- ↑ Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Epilogue. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-legalism/#EpiLegChiHis

- ↑ Ross Terril 2003 p.68. The New Chinese Empire

- ↑ Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, p.59 The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy https://books.google.com/books?id=I0iMBtaSlHYC&pg=PA59

- Chad Hansen, 1992 p.308 A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA308

- Ben-Ami Scharfstein 1995 p.21 Amoral Politics: The Persistent Truth of Machiavellism

- Ellen Marie Chen, 1975 p.17 Reason and Nature in the Han Fei-Tzu, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 2.

- Huang, Ray, China A Macro History

- Leonard Cottrel, 1962 p.138 The Tiger of Chin

- 1 2 Herrlee G. Creel, 1974 p.124. Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1.

- 1 2 K. K. Lee, 1975 p.24. Legalist School and Legal Positivism, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 2.

- ↑ Edward L. Shaughnessy. China Empire and Civilization p26

- ↑ Rickett, Guanzi. p. 3

- 1 2 http://khayutina.userweb.mwn.de/LEGALISM_2013/FILES/Hulsewe_Legalists_Qin_Laws.pdf A. F. P. Hulsewe. THE LEGALISTS AND THE LAWS OF CH'IN. p1

- ↑ Zhengyuan Fu, 1996 China's Legalists p.4-5

- ↑ Herrlee G. Creel, Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1

- ↑ Zhengyuan Fu, 1996 China's Legalists p.4

- ↑ Peng He 2014. p.81. Chinese Lawmaking: From Non-communicative to Communicative. https://books.google.com/books?id=MXDABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA81

- 1 2 Eileen Tamura 1997 p.54. China: Understanding Its Past, Volume 1. https://books.google.com/books?id=O0TQ_Puz-w8C&pg=PA54

- ↑ Chen, Chao Chuan an Yueh-Ting Lee 2008 p.12-13. Leadership and Management in China

- ↑ Creel,What Is Taoism?, 107

- 1 2 Mark Edward Lewis, 1999 p.22, Writing and Authority in Early China

- ↑ Creel, What Is Taoism?, 94

- Mark Edward Lewis, 1999 p.18-19, Writing and Authority in Early China

- Paul R. Goldin, p.16 Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism. http://www.academia.edu/24999390/Persistent_Misconceptions_about_Chinese_Legalism_

- ↑ http://www.indiana.edu/~p374/Legalism.pdf R Eno, Indiana University

- ↑ Ricket, Guanzi (1985) p.10

- ↑ Joanna Handlin Smith 2009 p.252. The Art of Doing Good: Charity in Late Ming China

- 1 2 Source: Luo Shilie 羅世烈 (1992), "Zichan 子產", in: Zhongguo da baike quanshu 中國大百科全書, Zhongguo lishi 中國歷史 (Beijing/Shanghai: Zhongguo da baike quanshu chubanshe), Vol. 3, p. 1620. http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Zhou/personszichan.html

- ↑ Karen G. Turner p.1. The Limits of the Rule of Law in China. https://books.google.com/books?id=h_kUCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1

- Luo Shilie 羅世烈 (1992), "Zichan 子產", in: Zhongguo da baike quanshu 中國大百科全書, Zhongguo lishi 中國歷史 (Beijing/Shanghai: Zhongguo da baike quanshu chubanshe), Vol. 3, p. 1620. http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Zhou/personszichan.html

- ↑ Aspects of Legalist Philosophy and the Law in Ancient China. Matthew August LeFande

- ↑ Walker, Robert Louis. The Multi-state System of Ancient China. 1953.

- ↑ A History of Chinese Philosophy (1952). Youlan Feng, Derk Bodde. p76

- ↑ Chinese University Press. Mozi, Ian Johnston. p 28. Translation of a distillation of Mohist thought. Faber (1877) p. 4.

- ↑ Mohist Thought. Indiana University, Early Chinese Thought [B/E/P374] – Fall 2010 (R. Eno). p1

- ↑ Chinese University Press. Mozi, Ian Johnston. p xxii

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fraser, Chris, "Mohism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2015/entries/mohism/

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.145,147. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA145

- ↑ Jacques Gernet 1982 p.91. A History of Chinese Civilization. https://books.google.com/books?id=jqb7L-pKCV8C&pg=PA91

- ↑ Mark Edward Lewis 2010. p.237-238. The Early Chinese Empires

- ↑ Chad Hansen. Philosophy of Language in Classical China. http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/lang.htm

- ↑ Chad Hansen. Philosophy of Language in Classical China. http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/lang.htm

- ↑ Creel, 1974 p.59 Shen Pu-hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B.C.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet 1982 p.91. A History of Chinese Civilization. https://books.google.com/books?id=jqb7L-pKCV8C&pg=PA91

- 1 2 3 4 Chad Hansen, 1992 p.348-349 A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA348

- ↑ Chad Hansen. Philosophy of Language in Classical China. http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/lang.htm

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.143. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA143

- Chad Hansen, 1992 p.348-349 A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA348

- Chad Hansen. Philosophy of Language in Classical China. http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/lang.htm

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.143. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA143

- 1 2 Zhongying Cheng 1991 p.315. New Dimensions of Confucian and Neo-Confucian Philosophy. https://books.google.com/books?id=zIFXyPMI51AC&pg=PA315

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.143. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA143

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.143. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA143

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.145,147. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA145

- 1 2 Paul R. Goldin, Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism. p.19 http://www.academia.edu/24999390/Persistent_Misconceptions_about_Chinese_Legalism_

- ↑ Chad Hansen, 1992 p.349 A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA349

- Bo Mou 2009 p.145. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA145

- Zhongying Cheng 1991 p.314. New Dimensions of Confucian and Neo-Confucian Philosophy. https://books.google.com/books?id=zIFXyPMI51AC&pg=PA314

- ↑ Robins, Dan, "Xunzi", 3. Fa (Models), Teachers, and Gentlemen, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/xunzi/

- ↑ Chad Hansen, Shen Buhai http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/Shen%20Bu%20Hai.htm

- 1 2 3 Chad Hansen, University of Hong Kong. Lord Shang. http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/Lord%20Shang.htm

- ↑ Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, p.59. The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. https://books.google.com/books?id=I0iMBtaSlHYC&pg=PA59

- Chad Hansen, 1992 p.347-348. A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought. https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA345

- Fraser, Chris, "Mohism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2015/entries/mohism/

- Paul R. Goldin, Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism p.6 http://www.academia.edu/24999390/Persistent_Misconceptions_about_Chinese_Legalism_

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.143-144. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA143

- ↑ Bo Mou 2009 p.147. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy Volume 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=UL1-AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA143

- ↑ Chad Hansen, 1992 p.346,349,366 A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA346

- ↑ DENIS TWITCHETT and JOHN K. FAIRBANK, 2008. p.75 CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF CHINA

- ↑ Zhang, Guohua, "Li Kui". Encyclopedia of China (Law Edition), 1st ed.