Lawrence Ferlinghetti

| Lawrence Ferlinghetti | |

|---|---|

|

Lawrence Ferlinghetti at City Lights in 2007 | |

| Born |

Lawrence Monsanto Ferling March 24, 1919 Yonkers, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet, activist, essayist, painter |

| Literary movement | Beat poetry |

| Spouse | Selden Kirby-Smith (1951–1976)[1] |

| Children | Julie and Lorenzo[1] |

Lawrence Monsanto Ferlinghetti (born March 24, 1919) is an American poet, painter, liberal activist, and the co-founder of City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. Author of poetry, translations, fiction, theatre, art criticism, and film narration, he is best known for A Coney Island of the Mind (1958), a collection of poems that has been translated into nine languages, with sales of more than one million copies.[2]

Early life

Lawrence Ferlinghetti was born on March 24, 1919 in Bronxville, New York.[3] His mother, Albertine Mendes-Monsanto (born in Lyon, France) was of French/Portuguese Sephardic heritage. The Mendes-Monsanto family is the family which the Monsanto Chemical company is named for, the chemical company's founder's father-in-law being Emmanuel Mendes-Monsanto.

His father, Carlo Ferlinghetti, was born in Chiari, a small town in the province of Brescia, Italy on March 14, 1872. He immigrated to the United States in 1894,[4] was naturalized in 1896, and worked as an auctioneer in Little Italy, of New York City. At some unknown point, Carlo Ferlinghetti shortened the family name to "Ferling," and Lawrence would not learn of his original family name until 1942, when he had to provide a birth certificate to join the U.S. Navy. Although he used "Ferling" for his earliest published work, Ferlinghetti reverted to the original Italian "Ferlinghetti" in 1955, when publishing his first book of poems, Pictures of the Gone World.

Ferlinghetti's father died six months before he was born, and his mother was committed to an asylum shortly after his birth. He was raised by his French aunt Emily, the former wife of Ludovico Monsanto, an uncle of his mother from the Virgin Islands, who taught Spanish at the U.S. Naval Academy. Emily took Ferlinghetti to Strasbourg, France, where they lived during his first five years of his life, so he was raised speaking French as his first language.

After their return to the U.S., Ferlinghetti was placed in an orphanage in Chappaqua, New York while Emily looked for employment. She eventually was hired as a French governess for the daughter of Presley Eugene Bisland and his wife, Anna Lawrence Bisland, in Bronxville, New York, the latter being the daughter of the founder of Sarah Lawrence College, William Van Duzer Lawrence. They resided at the Plashbourne Estate.[5] In 1926, Ferlinghetti was left in the care of the Bislands. He later attended various schools including Riverdale Country School, Bronxville Public School, and Mount Hermon School (now Northfield Mount Hermon School). During these years, Ferlinghetti became an Eagle Scout in the Boy Scouts of America.[6][7][8] He attended the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where he earned a B.A. in journalism in 1941. His entry to the world of journalism was writing sports for The Daily Tar Heel,[9] and he published his first short stories in Carolina Magazine, for which Thomas Wolfe had written.

World War II

In the summer of 1941, he lived with two college mates on Little Whale Boat Island in Casco Bay, Maine, lobster fishing, and raking moss from rocks to be sold in Portland, Maine, for pharmaceutical use. This experience gave him a love of the sea, a theme that runs through much of his poetry. After the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Ferlinghetti enrolled in midshipmen’s school in Chicago, and in 1942 shipped out as junior officer on J. P. Morgan III's yacht, which had been refitted to patrol for submarines off the East Coast.

Next, Ferlinghetti was assigned to the Ambrose Lightship outside New York harbor, to identify all incoming ships. In 1943 and 1944, he served as an officer on three U.S. Navy subchasers used as convoy escorts. As commander of the submarine chaser USS SC1308, he was at the Normandy invasion as part of the anti-submarine screen around the beaches. After VE Day, the Navy transferred him to the Pacific Theater, where he served as navigator of the troop ship USS Selinur. Six weeks after the atomic bomb fell on Nagasaki, he visited the ruins of the city, an experience that turned him into a lifelong pacifist.

Columbia University and The Sorbonne

After the war, he worked briefly in the mailroom at Time magazine, in Manhattan. The G.I. Bill then enabled him to enroll in the graduate school of Columbia University. Among his professors there were Babette Deutsch, Lionel Trilling, Jacques Barzun, and Mark Van Doren. In those years he was reading modern literature, and has said that at that time, he was influenced particularly by Shakespeare, Marlowe, the Romantic poets, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and James Joyce, as well as American poets Whitman, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Carl Sandburg, Vachel Lindsay, Marianne Moore, E. E. Cummings, and American novelists Thomas Wolfe, Ernest Hemingway, and John Dos Passos. He earned a master's degree in English literature in 1947 with a thesis on John Ruskin and the British painter J. M. W. Turner. From Columbia, he went to Paris to continue his studies and lived in the city between 1947 and 1951, earning a Doctorat de l’Université de Paris, with a "mention très honorable." His two theses were on the city as a symbol in modern poetry and on the nature of Gothic.[10]

He met his future wife, Selden Kirby-Smith, granddaughter of Edmund Kirby-Smith, in 1946 aboard a ship en route to France. They both were heading to Paris to study at the Sorbonne. Kirby-Smith went by the name Kirby.[10]

San Francisco – City Lights Books

After marrying in 1951 in Duval County, Florida, they settled in San Francisco in 1953, where he taught French in an adult education program, painted, and wrote art criticism. His first translations, of poems by the French surrealist Jacques Prévert, were published by Peter D. Martin in his popular culture magazine City Lights.

In 1953, Ferlinghetti and Martin founded City Lights Bookstore, the first all-paperbound bookshop in the country. Two years later, after the departure of Martin, Ferlinghetti launched the publishing wing of City Lights with his own first book of poems, Pictures of the Gone World, the first number in the Pocket Poets Series. This volume was followed by books by Kenneth Rexroth, Kenneth Patchen, Marie Ponsot, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Kaufman, Denise Levertov, Robert Duncan, William Carlos Williams, and Gregory Corso. Although City Lights Publishers is best known for its publication of Beat Generation writers, Ferlinghetti never intended to publish the Beats exclusively, and the press has always maintained a strong international list.

City Lights Publishers expanded its list from poetry to include prose, including novels, biography, memoirs, essays, and cultural studies. In 1972, City Lights published a collection of short stories by Charles Bukowski, Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions, and General Tales of Ordinary Madness (since republished in two volumes, Tales of Ordinary Madness and The Most Beautiful Woman in Town). Subsequently it took over publication of Bukowski's collection of "Notes of a Dirty Old Man" columns for Open City from the pornography publisher Essex House in the early 1970s. Since then, it has published a sequel to Notes and a book of ephemera by Bukowski.

Other prose works include Neal Cassady's memoir The First Third, Edie Kerouac-Parker's memoir of her life with Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs's The Yage Letters to Allen Ginsberg, and other ephemera. It has also published political books by prominent authors, including Noam Chomsky, Tom Hayden, and Howard Zinn. Books published in translation include such authors as Georges Bataille, Bertolt Brecht, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Howl trial

The fourth number in the Pocket Poets Series was Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. Ferlinghetti was in attendance at the now-famous Six Gallery reading where Ginsberg first performed Howl publicly. The next day Ferlinghetti wired Ginsberg: "I greet you at the beginning of a great literary career," subsequently offering to publish his work.

The book was seized in 1956 by the San Francisco police. Ferlinghetti and Shig Murao, the bookstore manager who had sold the book to the police, were arrested on obscenity charges. After charges against Murao were dropped, Ferlinghetti, defended by Jake Ehrlich and the American Civil Liberties Union, stood trial in San Francisco Municipal court. The publicity generated by the trial drew national attention to San Francisco Renaissance and Beat movement writers. Ferlinghetti had the support of prestigious literary and academic figures, and, at the end of a long trial, Judge Clayton W. Horn found Howl not obscene, and acquitted him in October 1957. The landmark First Amendment case established a key legal precedent for the publication of other controversial literary work with redeeming social importance.

In 2010, Andrew Rogers portrayed Ferlinghetti in the film Howl.[11]

Beat writers

Although in style and theme, Ferlinghetti’s own writing is very unlike that of the original New York Beat circle, he had important associations with the Beat writers, who made City Lights Bookstore their headquarters when they were in San Francisco. He often has claimed that he was not a Beat, but a bohemian of an earlier generation. A married war veteran and a bookstore proprietor, he did not share the high (or low) life of the Beats on the road. Jack Kerouac wrote Ferlinghetti into the character “Lorenzo Monsanto” in his autobiographical novel, Big Sur (1962), the story of Kerouac’s stay (with the Cassadys, the McClures, Lenore Kandel, Lew Welch, and Philip Whalen) at Ferlinghetti’s cabin in the wild coastal region of Big Sur. Kerouac depicts the Ferlinghetti figure as a generous and good-humored host, in the midst of Dionysian revels and breakdowns.

Over the years Ferlinghetti published work by many of the Beats, including Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, William S. Burroughs, Diane diPrima, Michael McClure, Philip Lamantia, Bob Kaufman, and Gary Snyder. He was Ginsberg’s publisher for more than thirty years. When the Indian poets of the Hungryalists literary movement were arrested in 1964 at Kolkata, Ferlinghetti introduced the Hungryalist poets to Western readers through the initial issues of City Lights Journal.

Poetry

| “ | If you would be a poet, create works capable of answering the challenge of apocalyptic times, even if this meaning sounds apocalyptic. You are Whitman, you are Poe, you are Mark Twain, you are Emily Dickinson and Edna St. Vincent Millay, you are Neruda and Mayakovsky and Pasolini, you are an American or a non-American, you can conquer the conquerors with words.... |

” | |

| — Lawrence Ferlinghetti. From Poetry as Insurgent Art [I am signaling you through the flames]. | |||

Ferlinghetti takes a distinctly populist approach to poetry, emphasizing throughout his work that, “art should be accessible to all people, not just a handful of highly educated intellectuals”.[12] This perception of art as a broad sociocultural force, as opposed to an elitist academic enterprise, is explicitly evident in Poem 9 from Pictures of the Gone World, wherein the speaker states: “‘Truth is not the secret of a few’ / yet / you would maybe think so / the way some / librarians / and cultural ambassadors and / especially museum directors / act” (1-8). In addition to Ferlinghetti’s aesthetic egalitarianism, this passage highlights two additional formal features of the poet’s work, namely, his incorporation of a common American idiom as well as his experimental approach to line arrangement which, as Crale Hopkins notes, is inherited from the poetry of William Carlos Williams.[13]

Reflecting his broad aesthetic concerns, Ferlinghetti’s poetry often engages with several non-literary artistic forms, most notably jazz music and painting. Considering the former, as William Lawlor asserts, much of Ferlinghetti’s free verse attempts to capture the spontaneity and imaginative creativity of modern jazz; the poet is also notable for frequently incorporating jazz accompaniments into public readings of his work.[14]The significance of painting to Ferlinghetti’s verse is evidenced by the fact that many his poems engage in ekphrasis, with a notable example of this being found in the poem, “In Goya’s Greatest Scenes We Seem to See…”. Here, Ferlinghetti offers a poetic engagement with the paintings of renowned Spanish artist Francisco Goya, relating the suffering of the painter’s figures who, “writhe upon the page / in a veritable rage / of adversity” (6-8), to the existential plight of modern Americans trapped in a monstrously materialistic society.

Although imbued with the commonplace, Ferlinghetti’s poetry is grounded in lyric and narrative traditions. Among his themes are the beauty of natural world, the tragicomic life of the common human, the plight of the individual in mass society, and the dream and betrayal of democracy. He counts among his influences T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, e. e. cummings, H.D., Marcel Proust, Charles Baudelaire, Jacques Prévert, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Blaise Cendrars. One of his poems, 'Two Scavengers in a Truck, Two Beautiful People in a Mercedes', is now a poem studied at GCSE level in England and Wales, as part of the collection of poems in the AQA Anthology. His famous poem "Just As I Used to Say', was published in 1976, when Ferlinghetti was aged 57.

Political engagement

Soon after settling in San Francisco in 1950, Ferlinghetti met the poet Kenneth Rexroth, whose concepts of philosophical anarchism influenced his political development. He self-identifies as a philosophical anarchist, regularly associated with other anarchists in North Beach, and he sold Italian anarchist newspapers at the City Lights Bookstore.[15] A critic of U.S. foreign policy, Ferlinghetti has taken a stand against totalitarianism and war.

While Ferlinghetti has expressed that he is "an anarchist at heart," he concedes that the world would need to be populated by "saints" in order for pure anarchism to be lived practically. Hence he espouses what can be achieved by Scandinavian-style democratic socialism.[16]

Ferlinghetti's work challenges the definition of art and the artist’s role in the world. He urged poets to be engaged in the political and cultural life of the country. As he writes in Populist Manifesto: "Poets, come out of your closets, Open your windows, open your doors, You have been holed up too long in your closed worlds... Poetry should transport the public/to higher places/than other wheels can carry it..."

On January 14, 1967, he was a featured presenter at the Gathering of the tribes "Human Be-In," which drew tens of thousands of people and launched San Francisco's "Summer of Love." In 1968, he signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.[17]

Ferlinghetti was instrumental in bringing poetry out of the academy and back into the public sphere with public poetry readings. With Ginsberg and other progressive writers, he took part in events that focused on such political issues as the Cuban revolution, the nuclear arms race, farm-worker organizing, the murder of Salvador Allende, the Vietnam War, May ’68 in Paris, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Mexico. He read not only to audiences in the United States, but widely in Europe and Latin America. Many of his writings grew from travels in France, Italy, the Soviet Union, Cuba, Mexico, Chile, Nicaragua, and the Czech Republic.

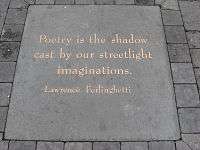

In 1998, in his inaugural address as Poet Laureate of San Francisco, Ferlinghetti urged San Franciscans to vote to remove a portion of the earthquake-damaged Central Freeway and replace it with a boulevard. "What destroys the poetry of a city? Automobiles destroy it, and they destroy more than the poetry. All over America, all over Europe in fact, cities and towns are under assault by the automobile, are being literally destroyed by car culture. But cities are gradually learning that they don't have to let it happen to them. Witness our beautiful new Embarcadero! And in San Francisco right now we have another chance to stop Autogeddon from happening here. Just a few blocks from here, the ugly Central Freeway can be brought down for good if you vote for Proposition E on the November ballot."[18] Since 1998, Ferlinghetti has championed creation of a Poets Plaza on the block of Vallejo Street between Grant and Columbus avenues, near City Lights Bookstore. The project would close the block to auto traffic, and create "a great public space where writers of all generations and nationalities could come and recite their works (with quotes from great poets incised in the paving stone) — a plaza that would become the active literary center of the city."[19]

In March 2012, he added his support to the movement to save the Gold Dust Lounge, a historic Gold Rush-era bar in San Francisco, which lost its lease in Union Square.

Painting

Ferlinghetti began painting while in Paris in 1948. In San Francisco, he occupied a studio at 9 Mission Street on the Embarcadero in the 1950s that he inherited from Hassel Smith, and subsequently passed on to the artist Howard Hack. He admired the New York abstract expressionists, and his first work exhibits their influence. A more figurative style is apparent in his later work. Ferlinghetti’s paintings have been shown at various museums around the world, from solo shows at the Butler Institute of American Art[20] to Il Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome. Other solo exhibitions include Sonoma Valley Museum of Art in 2012, and Marin Museum of Contemporary Art in 2014. He has been associated with the international Fluxus movement through the Archivio Francesco Conz in Verona. Ferlinghetti's artwork is represented by Rena Bransten Gallery in San Francisco, and was previously shown for many years at George Krevsky Gallery.

In 2009 Ferlinghetti became a member of the Honour Committee of the Italian artistic literary movement IMMAGINE&POESIA, founded under the patronage of Aeronwy Thomas. A retrospective of Ferlinghetti's artwork, 60 years of painting, was staged in Rome and Reggio Calabria in 2010.[21]

Jack Kerouac Alley

In 1987, he was the initiator of the transformation of Jack Kerouac Alley, located at the side of his shop. He presented his idea to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors calling for repavement and renewal.[22] Since 1991, young volunteers from the Adopt-An-Alleyway Youth Empowerment Project – a program run by the Chinatown Community Development Center – have maintained the good condition of the alley, which is a bridge between Chinatown and North Beach.[23]

Awards

He has received numerous awards, including the Los Angeles Times’ Robert Kirsch Award, the BABRA Award for Lifetime Achievement, the National Book Critics Circle Ivan Sandrof Award for Contribution to American Arts and Letters, and the ACLU Earl Warren Civil Liberties Award. He won the Premio Taormino in 1973, and since then has been awarded the Premio Camaiore, the Premio Flaiano, the Premio Cavour, among other honors in Italy. Ferlinghetti was named San Francisco’s Poet Laureate in August 1998 and served for two years. In 2003 he was awarded the Robert Frost Memorial Medal, the Author’s Guild Lifetime Achievement Award, and he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2003. The National Book Foundation honored him with the inaugural Literarian Award (2005), given for outstanding service to the American literary community. In 2007 he was named Commandeur, French Order of Arts and Letters. In 2012, Ferlinghetti received the Douglas MacAgy Distinguished Achievement Award from the San Francisco Art Institute.

In 2012, Ferlinghetti was awarded the inaugural Janus Pannonius International Poetry Prize from the Hungarian PEN Club. After learning that the government of Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is a partial sponsor of the €50,000 prize, he declined to accept the award. In declining, Ferlinghetti cited his opposition to the "right wing regime" of Prime Minister Orban, and his opinion that the ruling Hungarian government under Mr. Orban is curtailing civil liberties and freedom of speech for the people of Hungary.[24][25][26][27]

In popular culture

The Italian band Timoria dedicated the song "Ferlinghetti Blues" (from the album El Topo Grand Hotel) to the poet, where Ferlinghetti recites one of his poems. Recordings of Ferlinghetti reading want ads, as featured on radio station KPFA in 1957, were recorded by Henry Jacobs and are featured on the Meat Beat Manifesto album 'At the Center'. Ferlinghetti gave Canadian punk band Propagandhi permission to use his painting The Unfinished Flag of the United States, which features a map of the world painted in the stars and stripes, as the cover of their 2001 release Today's Empires, Tomorrow's Ashes. Before this, the same painting was used for the cover of Michael Parenti's 1995 book, Against Empire, which was published by City Lights.

Ferlinghetti recited the poem Loud Prayer at The Band's final performance. Entitled The Last Waltz, this concert was filmed by Martin Scorsese and released as a documentary which included Ferlinghetti's recitation. Julio Cortázar, in his Rayuela (Hopscotch) (1963) references a poem by Ferlinghetti in Chapter 121. He appears as himself in the 2006 comedy film The Darwin Awards. Bob Dylan used Ferlinghetti's "Baseball Canto" on the Baseball show of Theme Time Radio Hour. Roger McGuinn, the former leader of the Byrds, referred to Ferlinghetti and "A Coney Island of the Mind" in his song "Russian Hill", from his 1977 album Thunderbyrd. Cyndi Lauper was inspired by A Coney Island of the Mind to write the song "Into the Nightlife" for her 2008 album Bring Ya to the Brink. Seamus McNally's 2007 filmed adaptation of Jacques Prévert's "To Paint the Portrait of a Bird" uses Ferlinghetti's English translation as it's narrative text. The Residents mention Ferlinghetti in the lyrics of their song "Sinister Exaggerator" (from the EP "Duck Stab").

The Blue Devils Drum and Bugle Corps's 2008 marching show was entitled "Constantly Risking Absurdity", with movements entitled after various lines in Ferlinghetti's poem. The corps took second place at the Drum Corps International Finals. Aztec Two-Step is an American folk-rock band formed by Rex Fowler and Neal Shulman at a chance meeting on open stage at a Boston coffee house, the Stone Phoenix, in 1971. The band was named after a line from the poem "A Coney Island of the Mind" by Ferlinghetti. Bristol Sound band Unforscene used Ferlinghetti's poem "Pictures of the Gone World 11" (or "The World is a Beautiful Place...") in the song "The World Is" on its 2002 album New World Disorder.

In 2011, Ferlinghetti contributed two of his poems to the celebration of the 150th Anniversary of Italian unification: Song of the Third World War and Old Italians Dying inspired the artists of the exhibition Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Italy 150 held in Turin, Italy (May–June 2011).[28]

Christopher Felver made the 2013 documentary on Ferlinghetti, Lawrence Ferlinghetti: A Rebirth of Wonder.[29]

Ferlinghetti prefers association football to American football.[30]

Bibliography

| Library resources about Lawrence Ferlinghetti |

| By Lawrence Ferlinghetti |

|---|

- Pictures of the Gone World (City Lights, 1955) Poetry (enlarged, 1995) ISBN 978-0-87286-303-3

- A Coney Island of the Mind ( New Directions, 1958) Poetry

- Tentative Description of a Dinner Given to Promote the Impeachment of President Eisenhower (Golden Mountain Press, 1958) Broadside poem

- Her (New Directions, 1960) Prose

- One Thousand Fearful Words for Fidel Castro (City Lights, 1961) Broadside poem

- Starting from San Francisco (New Directions, 1961) Poetry (HC edition includes LP of author reading selections)

- Journal for the Protection of All Beings (City Lights, 1961) Journal

- Unfair Arguments with Existence (New Directions, 1963) Short Plays

- Where is VietNam? (Golden Mountain Press, 1963) Broadside poem

- Routines (New Directions, 1964) 12 Short Plays

- Two Scavengers in a Truck, Two Beautiful People in a Mercedes (1968)

- On the Barracks: Journal for the Protection of All Beings 2 (City Lights, 1968) Journal

- Tyrannus Nix? (New Directions, 1969) Poetry

- The Secret Meaning of Things (New Directions, 1970) Poetry

- The Mexican Night (New Directions, 1970) Travel journal

- Back Roads to Far Towns After Basho (City Lights, 1970) Poetry

- Love Is No Stone on the Moon (ARIF, 1971) Poetry

- Open Eye, Open Heart (New Directions, 1973) Poetry

- Who Are We Now? (New Directions, 1976) Poetry

- Northwest Ecolog (City Lights, 1978) Poetry

- Landscapes of Living and Dying (1980) ISBN 0-8112-0743-9

- Over All the Obscene Boundaries (1986)

- Love in the Days of Rage (E. P. Dutton, 1988; City Lights, 2001) Novel

- A Buddha in the Woodpile (Atelier Puccini, 1993)

- These Are My Rivers: New & Selected Poems, 1955–1993 (New Directions, 1993) ISBN 0-8112-1252-1

- City Lights Pocket Poets Anthology (City Lights, 1995) ISBN 978-0-87286-311-8

- A Far Rockaway Of The Heart (New Directions, 1998) ISBN 0-8112-1347-1

- How to Paint Sunlight: Lyrics Poems & Others, 1997–2000 (New Directions, 2001) ISBN 0-8112-1463-X

- San Francisco Poems (City Lights Foundation, 2001) Poetry ISBN 978-1-931404-01-3

- Life Studies, Life Stories (City Lights, 2003) ISBN 978-0-87286-421-4

- Americus: Part I (New Directions, 2004)

- A Coney Island of the Mind (Arion Press, 2005), with portraiture by R.B. Kitaj

- Poetry as Insurgent Art (New Directions, 2007) Poetry

- A Coney Island of the Mind: Special 50th Anniversary Edition with a CD of the author reading his work (New Directions, 2008)

- 50 Poems by Lawrence Ferlinghetti 50 Images by Armando Milani ( Rudiano, 2010) Poetry and Graphics ISBN 978-88-89044-65-0

- Time of Useful Consciousness, (Americus, Book II) (New Directions, 2012) ISBN 978-0-8112-2031-6, 88p.

- City Lights Pocket Poets Anthology: 60th Anniversary Edition (City Lights, 2015)

- I Greet You At The Beginning Of A Great Career: The Selected Correspondence of Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg 1955-1997. (City Lights, 2015)

- Pictures of the Gone World: 60th Anniversary Edition (City Lights, 2015)

Discography

- Kerouac: Kicks Joy Darkness (Track #8 "Dream: On A Sunny Afternoon..." with Helium) (1997) Rykodisc

- Poetry Readings in the Cellar (with the Cellar Jazz Quintet): Kenneth Rexroth & Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1957) Fantasy Records #7002 LP, (Spoken Word)

- Ferlinghetti: The Impeachment of Eisenhower (1958) Fantasy Records #7004 LP, (Spoken Word)

- Ferlinghetti: Tyrannus Nix? / Assassination Raga / Big Sur Sun Sutra / Moscow in the Wilderness (1970) Fantasy Records #7014 LP, (Spoken Word)

- A Coney Island of the Mind (1999) Rykodisc

- Pictures of the Gone World with David Amram (2005) Synergy

See also

References

- 1 2 "Lawrence Ferlinghetti Biography". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ Mark Howell (2007-09-30). "About The Beats: The Key West Interview: Lawrence Ferlinghetti, 1994". Abouthebeats.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ "Academic.Brooklyn". Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s italianita. Retrieved October 30, 2006.

- ↑ "Carlo Ferlinghetti, Italy - New York immigration record 10-20-1894, Male 22 years". Italianimmigrants.org. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ Phillip Seven Esser and Paul Graziano (August 2006). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Plashbourne Estate". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ↑ "Lawrence Ferlinghetti".

- ↑ "Lawrence Ferlinghetti-American poet, playwright, and publisher".

- ↑ Alex Vig. "The Lawrence Lyrics".

- ↑ Zinser, Lynn (January 20, 2012). "Lawrence Ferlinghetti Revives His Love of the 49ers at 92". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Julian Guthrie (2012-09-24). "Lawrence Ferlinghetti's indelible image". SFGate. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ Howl 2010 Film at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Lawrence Ferlinghetti". Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Hopkins, Crale (1974). "The Poetry of Lawrence Ferlinghetti: A Reconsideration". Italian Americana. 1 (1): 59-76. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Lawlor, William (2005). Beat Culture: Lifestyles, Icons, and Impact. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 34–37. ISBN 9781851094059. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, Kevin (Winter 1988). "Lawrence Ferlinghetti – interview". Whole Earth Review (61). "I'm in the anarchist tradition. By "anarchist" I don't mean someone with a homemade bomb in his pocket. I mean philosophical anarchism in the tradition of Herbert Reed in England."

- ↑ Felver, Christopher. 1996 The Coney Island of Lawrence Ferlinghetti. San Francisco: Mystic Fire Video [documentary film]

- ↑ “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” January 30, 1968 New York Post

- ↑ "Poetry and City Culture". Address at the San Francisco Public Library, October 13th 1998. Accessed February 19, 2016.

- ↑ Beyl, Ernest. "Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Grand Vision: The Poets Plaza". Marina Times, August 2015. Accessed February 19, 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ Lawrence Ferlinghetti: 60 years of painting, edited by Giada Diano and Elisa Polimeni, Silvana Editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), 2009

- ↑ Nolte, Carl (March 30, 2007). "Kerouac Alley has face-lift". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Adopt an alley". Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ↑ Christopher Young (October 12, 2012). "Beat this: Lawrence Ferlinghetti refuses Hungarian cash award". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ Carolyn Kellogg (October 11, 2012). "Lawrence Ferlinghetti declines Hungarian award over human rights". LA Times. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ Ron Friedman and AP (October 13, 2012). "Following Elie Wiesel's Lead, US Poet Rejects Hungarian Award". The Times of Israel. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ Harriet Staff (October 11, 2012). "Lawrence Ferlinghetti Declines 50,000 Euro Prize from Hungarian PEN Club". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Evento Ferlinghetti: La poesia incontra l'arte" (PDF). LA STAMPA. Arte Citta' Amica. 2001-06-03. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ↑ "A Beat-Generation Star Who Won't Answer to the Name". New York Times. Feb 7, 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ "MMQB (cont.)". Sports Illustrated. January 23, 2012.

Further reading

- Ann Charters (ed.), The Portable Beat Reader. Penguin Books. New York. 1992.

- Neeli Cherkovski, Ferlinghetti: A Biography. New York: Doubleday, 1979.

- Ronald Collins and David Skover, Mania: The Story of the Outraged & Outrageous Lives that Launched a Cultural Revolution. Top-Five Books, 2013.

- Bill Morgan (ed.), I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career: The Selected Correspondence of Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg, 1955-1997. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers, 2015.

- Walter Pescara, Lawrence Ferlinghetti – Italian Tour 2005. (Nicolodi, 2006 – special edition, not for sale)

- Barry Silesky, Ferlinghetti: The Artist in His Time. New York: Warner Books, 1990.

- Michael Skau, Constantly Risking Absurdity: The Writings of Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Whitson, 1989.

- Larry R. Smith, Lawrence Ferlinghetti: Poet-at-Large. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1983.

- Matt Theado, The Beats: A Literary Reference. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2003.

External links

- Guide to the Lawrence Ferlinghetti Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Guide to the photographs from the Lawrence Ferlinghetti papers, ca. 1935-ca. 1990 at The Bancroft Library

- Works by or about Lawrence Ferlinghetti in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti at The Soredove Press Limited Edition Poetry Chapbooks, Broadsides and Art

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti at The Beat Page Biography and Selected Poems.

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti at Literary Kicks

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti at American Poetry

- Kerouac Alley – Lawrence Ferlinghetti multimedia directory

- Amy Goodman Interview (Transcript and streaming media)

- Audio and video of reading at University of California Berkeley "Lunch Poems" series (December 1, 2005)

- Video interview with Lawrence Ferlinghetti about his paintings on KQED's Spark

- Proposed International Poetry Museum by Ferlinghetti friend Herman Berlandt

- Project with Immagine & Poesia for Italy 150

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti at the Internet Movie Database

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti in the Honour Committee of Immagine & Poesia

- Interview Magazine, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, by Christopher Bollen, May 2013

- 1978 audio interview, Lawrence Ferlinghetti with Stephen Banker

- Translated Penguin Book - at Penguin First Editions reference site of early first edition Penguin Books.