David's Tomb

| Hebrew: קבר דוד המלך | |

|

| |

Shown ( | |

| Location | Jerusalem |

|---|---|

| Region | Israel |

| Coordinates | 31°46′18″N 35°13′46″E / 31.77170°N 35.22936°E |

| Type | tomb |

| History | |

| Cultures | Ayyubid, Hebrew, Byzantine, Crusaders |

King David's Tomb (Hebrew: קבר דוד המלך) is a site viewed as the burial place of David, King of Israel, according to a tradition beginning in the 12th century. It is located on Mount Zion in Jerusalem, near the Hagia Maria Sion Abbey. The tomb is situated in a ground floor corner of the remains of the former Hagia Zion, a Byzantine church. Older Byzantine tradition dating to the 4th century identified the location as the Cenacle of Jesus and the original meeting place of the Christian faith. The building is now part of the Diaspora Yeshiva.

History

The tomb is located in a corner of a room situated on the ground floor remains of the former Hagia Zion an ancient house of worship; the upper floor of the same building has traditionally been viewed as the Cenacle of Jesus. The site of David's burial is unknown, though the Tanakh locates it southwards, in the Ir David near Siloam. In the 4th century CE, he and his father Jesse were believed to be buried in Bethlehem. The idea he was entombed on what was later called Mt Zion dates to the 9th century CE.[1] Writing around 1173 Benjamin of Tudela recounted a colourful story that two Jewish workers employed to dig a tunnel came across David's original splendid palace, replete with gold crown and scepter and decided the site must be his tomb. The Gothic cenotaph preserved to this day was constructed by the Crusaders:[1] the Mount Zion conquered by David according to the Book of Samuel was wrongly ascribed by medieval pilgrims to this site, and David was presumed to be buried there.[1]

In 1429, Mamluk Sultan Barsbay took part of the lower floor of the complex away from the Franciscans and converted the tomb chamber into a mosque.[2] Though it was returned a year later, possession alternated back and forth until 1524 when Ottoman Sultan Sulayman (Suleiman the Magnificent) expelled the Franciscans from the entire complex.[3] The resulting Islamic shrine was entrusted to Sufi Sheikh Ahmad Dajani and his posterity.

The Franciscan Monastery in Jerusalem during the 16th century did not encompass today's King David Tomb complex. In fact it was not a monastery but the residence of a small band of friars—in a room on the Western part of today's David Tomb because it was thought to be the site of the Last Supper [citation needed]. The friars used to throw their rubbish outside on the Eastern side of today's Tomb complex [?? citation needed]. The Sharif Ahmad Dajani, the first to hold the Dajani name, cleaned up the waste and constructed the neglected Eastern side of today's King David Tomb complex—where the tomb is located—in the 1490s [?? citation needed]. He established a place for Muslim prayer on the Eastern part of today's complex. The "Franciscans were driven out from the mountain" [?? citation needed] by residents of Jerusalem in 1524. The "Ibn Dawood" mosque, a title given Sheikh Ahmad Dajani by the residents of Jerusalem [?? citation needed], was established for Muslim prayers under the patronage of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and the supervision of al-Shareef Sheikh Ahmad bin Ali Dajani.[4]

Management of the site was transferred to the Muslim Palestinian family al-Ashraf Dajani al-Daoudi family (descendants of the Prophet Mohammad's grandson Hussein) by an edict from Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in 1529.[5] Since then, the Dajani family supervised and maintained this site. As a result, they were given the title of Dahoudi or Dawoodi by the residents of Jerusalem in reference to the King David Tomb complex.[6]

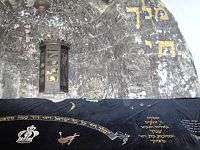

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the southern part of Mount Zion upon which the Tomb stands ended up on the Israel side of the Green Line. Between 1948 and 1967 the eastern part of the Old City was occupied by Jordan, which barred entry to Jews even for the purpose of praying at Jewish holy sites. Jewish pilgrims from around the country and the world went to David's Tomb and climbed to the rooftop to pray.[7] Since 1949, a blue cloth, with basic modernist ornamentation, has been placed over the sarcophagus. The images on the cloth include several crown-shaped Rimmon placed over Torah scrolls, and a violin, and the cloth also features several pieces of text written in Hebrew. The building is now part of the Diaspora yeshiva.

In December 2012, unknown persons completely destroyed a large number of 17th-century Islamic tiles in the tomb, and the Antiquities Authority decided to not reconstruct them.[8]

Question of authenticity

The contents of the sarcophagus have not yet been subjected to any scientific analysis, to determine their age, former appearance, or even whether there is actually still a corpse there.

The authenticity of the site has been challenged on several grounds. According to the Bible,[9] David was actually buried within the City of David together with his forefathers; by contrast, the 4th century Pilgrim of Bordeaux reports that he discovered David to be buried in Bethlehem, in a vault that also contained the tombs of Ezekiel, Jesse, Solomon, Job, and Asaph, with those names carved into the tomb walls.[10] The genuine David's Tomb is unlikely to contain any furnishings of value; according to the 1st-century writer Josephus, Herod the Great tried to loot the tomb of David, but discovered that someone else had already done so before him.[11] The 4th-century accounts of the Bordeaux Pilgrim, Optatus of Milevus, and Epiphanius of Salamis all record that seven synagogues had once stood on Mount Zion.[12] By 333 CE (the end of the Roman Period and beginning of the Byzantine Period) only one of them remained, but no association with David's tomb is mentioned.

According to the Book of Samuel, Mount Zion was the site of the Jebusite fortress called the "stronghold of Zion" that was conquered by King David, becoming his palace and the City of David.[13] It is mentioned in the Book of Isaiah (60:14), the Book of Psalms, and the first book of the Maccabees (c. 2nd century BCE).[13]

After the conquest of the Jebusite city, the hill of the Lower City was divided into several parts. The highest part, in the north, became the site of Solomon's Temple. Based on archaeological excavations revealing sections of the First Temple city wall, this is believed to have been the true Mount Zion.[14]

Towards the end of the First Temple period, the city expanded westward.[15] Just before the Roman conquest of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Second Temple, Josephus described Mount Zion as a hill across the valley to the west.[13] Thus, the western hill extending south of the Old City came to be known as Mount Zion, and this has been the case ever since.[13] It must however be said that Josephus never used the name "Mount Zion" in any of his writings, but described the "Citadel" of king David as being situated on the higher and longer hill, thus pointing at the Western Hill as what the Bible calls Mount Zion.[16][17]

At the end of the Roman period, a synagogue called Hagiya Zion was built at the entrance of the structure known as David's Tomb probably based on the belief that David brought the Ark of the Covenant here from Beit Shemesh and Kiryat Ye'arim before the construction of the Temple.[18] Others disagree. "Hagia Sion" (Holy Zion) was the Greek Christian name for the basilica built on the grounds in the late fourth century CE. What some scholars contend is that "David's Tomb" was actually once a late Roman synagogue.[19] The identification of David's Tomb as a synagogue has been thoroughly challenged due to the absence of typical synagogal architectural characteristics including (original) columns, benches, or similar accoutrements.[20] The presence of a niche in the original foundation walls, thought by a few to be evidence of a Torah niche, has been refuted by many scholars as being too large and too high (8' x 8') to have served this purpose.[21]

According to Doron Bar,

Although the sources for the tradition of David's Tomb on Mount Zion are not clear, it appears that it only began to take root during the subsequent, early Muslim period. Apparently, the Christians inherited this belief from the Muslims, and only at a relatively late juncture in the city’s history were the Jews finally convinced as well.[22]

Others disagree. The facility was under the control of Greek Christians at this time. It was, indeed, shortly before the Crusades at the earliest that the location of David's Tomb can be traced to Mount Zion.[23] But the first literary reference to the tomb being on Mount Zion can be found in tenth-century Vita Constantini (Life of Constantine).[24] And Ora Limor attributes the localizing of the tomb on Mount Zion to the desire of Roman/Latin Christians to infuse the spirit of the "founding fathers" into the site by imaginatively connecting it with the supposed tombs of David and Solomon.[25] Having initially revered David's tomb in Bethlehem, Muslims began to venerate it on Mount Zion instead but no earlier than the 10th century following the Christian (and possibly Jewish) lead. In the twelfth century, Jewish pilgrim Benjamin of Tudela recounted a somewhat fanciful tale of workmen accidentally discovering the tomb of David on Mount Zion.[26]

Epiphanius' 4th-century account in his Weights and Measures is one of the first to associate the location with the original meeting place of the Christian faith, writing that there stood "the church of God, which was small, where the disciples, when they had returned after the Savior had ascended from the Mount of Olives, went to the upper room".[27]

Archaeologists, doubting the Mount Zion location and favouring the biblical account, have since the early 20th century sought the actual tomb in the City of David area. In 1913, Raymond Weill found eight elaborate tombs at the south of the City of David,[28] which archaeologists have subsequently interpreted as strong candidates for the burial locations of the former kings of the city;[29] Hershel Shanks, for example, argues that the most ornate of these (officially labelled T1) is precisely where one would expect to find the burial site mentioned in the Bible.[30] Among those who agree with the academic and archaeological assessment of the Mount Zion site, some believe it actually is the tomb of a later king, possibly Manasseh, who is described in the Hebrew Bible as being buried in the Garden of the King rather than in the City of David like his predecessors.

In the mid-nineteenth century, engineer and amateur archaeologist Ermete Pierotti reported discovering a cavern beneath the grounds of the Byzantine and Crusader churches on Mount Zion which he suspected extended to beneath the Tomb of David.[31] A limited exploration revealed human remains within a huge vault supported by piers. The cavern has yet to be confirmed or scientifically excavated.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David's Tomb. |

- 1 2 3 Rabbi Dr. Ari Zivotofsky, 'Where is King David Really Buried?,' The Jewish Press, May 15th 2014.

- ↑ Pringle, Denys (2007). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus. Vol. 3. The City of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. p. 270.

- ↑ Pringle. Corpus. p. 271.

- ↑ Limor, Ora (Jan 1, 2007). "Sharing Sacred Space" in edited book In Laudem Hierosolymitani:. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 227.

- ↑ Feldinger, Lauren Gelfond (8 July 2013). "Israel and Vatican close to signing Holy Land accord". The Art Newspaper.

- ↑ "Dajani Daoudi Family Website".

- ↑ Jerusalem Divided: The Armistice Regime, 1947–1967, Raphael Israeli, Routledge, 2002, p. 6

- ↑ Nir Hasson (August 3, 2013). "Who is 'Judaizing' King David's Tomb?". Haaretz.

- ↑ 1 Kings 2:10

- ↑ Itinerarium Burdigalense 598:4-6

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 16:7:1

- ↑ Bordeaux Pilgrim, Itinerarium Burdigalense 20; Optatus of Milevus, Contra Donatistas 3.2; Epiphanius of Salamis, De Mensuris et Ponderibus 14 (54c).

- 1 2 3 4 Bargil Pixner (2010). Rainer Riesner, ed. Paths of the Messiah. Keith Myrick, Miriam Randall (trans.). Ignatius Press. pp. 320–322. ISBN 978-0-89870-865-3.

- ↑ This is Jerusalem, Menashe Harel, Canaan Publishing, Jerusalem, 1977, p.193, 272

- ↑ This is Jerusalem, Menashe Harel, Canaan Publishing, Jerusalem, 1977, p.272

- ↑ Flavius Josephus. The Wars of the Jews or History of the Destruction of Jerusalem. Translated by William Whiston. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved February 2016.

The city was built upon two hills, which are opposite to one another, and have a valley to divide them asunder; [...] Of these hills, that which contains the upper city is much higher, and in length more direct. Accordingly, it was called the "Citadel," by king David; [...] Now the Valley of the Cheesemongers, as it was called, and was that which we told you before distinguished the hill of the upper city from that of the lower,... (Book 5, Chapter 4, §1; or V:137)

Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ↑ The genuine works of Flavius Josephus..., translated by William Whiston, Havercamp edition, New York (1810). See footnote on page 83. (copy&pg=PA83 David's Tomb, p. 83, at Google Books)

- ↑ This is Jerusalem, Menashe Harel, Canaan Publishing, Jerusalem, 1977, p.273

- ↑ Jacob Pinkerfeld, "'David's Tomb': Notes on the History of the Building: Preliminary Report," in Bulletin of the Louis Rabinowitz Fund for the Exploration of Ancient Synagogues 3, ed. Michael Avi-Yonah, Jerusalem: Hebrew University, pp. 41-43.

- ↑ Clausen, David (2016). The Upper Room and Tomb of David: The History, Art and Archaeology of the Cenacle on Mount Zion. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 168–175. ISBN 9781476663050.

- ↑ Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide From Earliest Times to 1700, 5th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 117; Oskar Skarsaune, In the Shadow of the Temple: Jewish Influences on Early Christianity (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2002), 189; Joan Taylor, Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 215; Clausen, 158-163.

- ↑ Doron Bar (2004). "Re-creating Jewish Sanctity in Jerusalem: Mount Zion and David's Tomb, 1948–67". The Journal of Israeli History. 23 (2): 260–278.

- ↑ Pixner, Paths 352; Clausen, Upper Room 57.

- ↑ Anonymous, Vita Constantini 11.

- ↑ Ora Limor, "The Origins of a Tradition: King David's Tomb on Mount Zion," Traditio 44 (1988): 459.

- ↑ Benjamin of Tudela, Masa'ot Binyamin 85.

- ↑ Epiphanius of Salamis, Weights and Measures (1935) pp.11-83. English translation

- ↑ Kathleen Kenyon, Archaeology in the Holy Land (1985), p. 333.

- ↑ Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review, January/February 1995, p. 64.

- ↑ Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review, January/February 1995, p. 64.

- ↑ Ermete Pierotti, Jerusalem Explored: Being a Description of the Ancient and Modern City, 2 vols., trans. Thomas George Bonney (Cambridge: C. J. Clay, 1864), 215.

Coordinates: 31°46′17.9″N 35°13′44.45″E / 31.771639°N 35.2290139°E