Japanese Peruvians

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

3,949 Japanese nationals[1] 160,000 Peruvians of Japanese descent (Including Peruvians in Japan)[1][2][3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Lima, Trujillo, Huancayo, Chiclayo | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish, Japanese | |

| Religion | |

|

Predominantly Roman Catholicism, Buddhism, Shintoism[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chinese Peruvians, Japanese Americans, Japanese Canadians, Japanese Brazilians, Asian Latinos |

Japanese Peruvians (Spanish: peruano-japonés or nipo-peruano, Japanese: 日系ペルー人, Nikkei Perūjin) are Peruvian citizens of Japanese origin or ancestry.

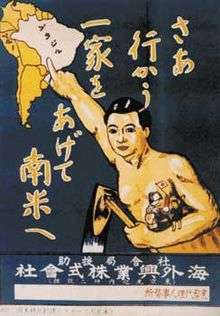

The Japanese began arriving in Peru in the late 1800s. Many factors motivated the Japanese to immigrate to Peru.

At the end of the nineteenth century in Japan, the rumor spread that a country called Peru somewhere on the opposite side of the earth was "full of gold". This country, moreover, was a paradise with a mild climate, rich soil for farming, familiar dietary customs, and no epidemics, according to advertisements of Japanese emigration companies. (Konno and Fujisaki, 1894) 790 Japanese, all men between the ages of 20 and 45, left Japan in 1898 to work on Peru's coastal plantations as contract laborers. Their purpose was simple: to earn and save money for the return home upon termination of their four-year contracts. The 25 yen monthly salary on Peru's plantations was more than double the average salary in rural Japan (Suzuki, 1992).

At the time of the First Sino-Japanese War, the economic state of Japan was poor. Because of the poor economic conditions in Japan, a surplus of skilled farmers in Japan occurred. Peru provided a new job market that was accommodating to the Japanese farmers. When the Japanese first arrived in Peru, the Peruvians welcomed the hard-work ethic of the Japanese worker. They provided the Peruvians with a cheap and productive labor source. After the population of Japanese immigrants grew in Peru, many Peruvian Japanese began opening small businesses. Peru has the second largest ethnic Japanese population in South America (Brazil has the largest) and this community has made a significant cultural impact on the country today approximately 1.4% of the population of Peru.[5]

Peru was the first Latin American country to establish diplomatic relations with Japan,[6] in June 1873.[7] Peru was also the first Latin American country to accept Japanese immigration.[6] The Sakura Maru carried Japanese families from Yokohama to Peru and arrived on April 3, 1899 at the Peruvian port city of Callao.[8] This group of 790 Japanese became the first of several waves of emigrants who made new lives for themselves in Peru, some nine years before emigration to Brazil began.[7]

Most immigrants arrived from Okinawa, Gifu, Hiroshima, Kanagawa and Osaka prefectures. Many arrived as farmers or to work in the fields but, after their contracts were completed, settled in the cities.[9] In the period before World War II, the Japanese community in Peru was largely run by issei immigrants born in Japan. "Those of the second generation [the nisei] were almost inevitably excluded from community decision-making."[10]

Beginnings

.jpg)

The Japanese Peruvian community began in 1899 when some 800 contract workers arrived in Callao Seaport in Lima. The Japanese migrants suffered from serious tropical diseases such as malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever, as well as discrimination due to race, language, and culture. Within a year, 143 had died and 93 fled to Bolivia (becoming the first Japanese immigrants in that country). A second ship, which brought over one thousand new Japanese immigrants, arrived four years later, and a third—with 774 Japanese immigrants—arrived in 1906 (Gardiner 1981: 3-4). By 1941 some 16,300 Japanese were living in Peru (10,300 from Okinawa and 6,000 from mainland Japan). Of these, only 3,300 were women (Masterson 2007: 148). Thus, unlike Brazil where farming family immigration was encouraged by the Brazilian authority for the migratory workers to settle in coffee plantations, single Japanese men but few women migrated to Peru. Most Japanese men married local women. Today, there are about 160,000 people of Japanese descent living in Peru, The majority are descendants of pre-war immigrants.

Unlike many other countries in Latin America, most Japanese immigrants did not settle on farms and plantations in Peru. They were able to move around to seek better opportunities and many migrated to the cities. Some worked for Japanese proprietors or started their own small businesses. By 1930, 45 percent of all Japanese in Peru ran small businesses in Lima. As in California, economic conflicts with local businesses quickly arose. The Eighty Percent Law passed in 1932 required that at least 80 percent of shop employees be non-Asian Peruvians. Furthermore, the Immigration Law of 1936 prohibited citizenship to children of alien parents, even if they were born in Peru. Peru was hardly the only country in the New World to take such actions. The United States prohibited citizenship for Asians at its inception in 1790, and reiterated it for Japanese in 1908 and 1924.

In 1940, an earthquake destroyed the city of Lima. By this time the community of Japanese and their wives and children was about 30,000 in Peru. Rumors spread that Japanese were looting.[1] As a result, some 650 Japanese houses were attacked and destroyed in Lima, an event resonating with the attack on Koreans in Japan at the time of the 1923 Kanto earthquake. Other harsh measures against Japanese-Peruvians followed. For example, in 1940 it was decreed that Japanese-Peruvians who went abroad to study in Japan would lose Peruvian citizenship.

In 1941, Peru broke off diplomatic relations with Japan after the Pearl Harbor attack and social and legal discrimination towards Japanese-Peruvians increased. All Japanese community institutions were disbanded, Japanese-language publications prohibited, and gatherings of more than three Japanese could constitute spying (Peru Simpo 1975 in Takenaka 2004:92). Japanese were not allowed to open businesses, and those who had a business were forced to auction them off. Japanese-owned deposits in Peruvian banks were frozen (Takenaka 2004:92). By 1942, Japanese were not even allowed to lease land (enacting laws jointly with the United States) (Gerbi 1943 in Takenaka 2004:92). The freedom of Japanese to travel outside their home communities was also restricted (Takenaka 2004:92).

These draconian measures were the result of agreements among the foreign ministers of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, the United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela in meetings in Rio de Janeiro. To bolster the security of all North and South America, they also recommended (1) the incarceration of dangerous enemy aliens, (2) the prevention of the descendants of enemy nationals to abuse their rights of citizenship to do things like criticize the government, (3) the regulation of international travel by enemy aliens and their families, and (4) the prevention of all acts of potential political aggression by enemy aliens, such as espionage, sabotage, and subversive propaganda (Gardiner 1981: 17).

Japanese schools in Peru

27 Japanese schools were founded in Peru (before the Second World War), which used school curricula created especially for overseas Japanese. The first Japanese school in Peru was founded in 1908 inside the Santa Barbara in the province of Canete. Many Japanese immigrants, with enough economic resources (or, in some cases, with little money but many children), could afford to send their children to Japan to study. This "exodus" of children prompted Andes Jiho newspaper to suggest, in 1914, the foundation of a local Japanese school in Lima in order to decrease the number of children who were sent to Japan to study. Six years later, in 1920, Lima Nikko was founded, which was the most important school in the Japanese society in Peru, because it was the first Japanese school with authorization to operate in Latin America given by the Ministry of Education of Japan. In Lima Nikko, as well as other local Japanese schools, classes were given both in Japanese and Spanish, and teaching, especially, Japanese history and culture.

Peru's current Japanese international school is Asociación Academia de Cultura Japonesa in Surco, Lima.[11]

Japanese-Peruvians and the United States

According to Gardiner (in Hirabayashi and Yano 2006: 160), 2,264 Latin Americans of Japanese descent were deported to the United States in 1942. Among those, at least 1,800 people were from Peru. Those Japanese who were on a “blacklist” at the American embassy in Peru were kidnapped and deported at gunpoint by the Peruvian police to internment camps in Texas and New Mexico. These deported “Japanese” included many people born in Peru (Gardiner 1981: 14-15; Hirabayashi and Kikumura-Yano 2007: 157). At these camps, the Japanese-Peruvians were joined by some 500 Japanese immigrants and their children from eleven other Latin American nations, (i.e., Bolivia,[2] Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama).[3] It is hard today to discern the precise reasons for these deportations. Patriotic wartime hysteria and political pressure from the United States were major contributing factors, but these simply added to the already extensive patterns of discrimination found in Peru. According to California Democratic congressman Xavier Becerra, one motive behind this action was to use these people as bargaining chips. Becerra and members of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Latin Americans of Japanese Descent Act (S 381 and H.R. 662) claim that some 800 Japanese Latin Americans in these camps were sent to Japan in exchange for captured American soldiers.[4] However, substantive evidence that these exchanges actually took place remains to be documented.

Life in the camps was not only a physical and economic struggle for Japanese-Peruvians, it also involved conflict with both non-Japanese Americans and Japanese Americans. Physically, the internment camps in the United States were like prisons, with residents surrounded by barbed-wire fences with armed guards. Physical conditions, especially at first, were stark. Each camp housed about 10,000 people, and conditions were often crowded. However, the residents gradually organized themselves, and by the end of the war something of a community had grown in each camp. There were newspapers, amateur theaters, schools, and sports teams. Many people had jobs, such as cooks, janitors, or health-care workers. As time passed, some Japanese were given a chance to be released temporarily from the camps to engage in agricultural work in local areas. But these opportunities were mostly limited to Japanese Americans, most of whom were either first-generation Japanese or their Nisei second-generation children born in the United States. They knew almost nothing about Peru or the Japanese Peruvians, and showed little interest in learning more. The feelings seemed mutual. This was especially true for the Nisei, most of whom thought of themselves simply as Americans or Peruvians and identified with the cultural and social values of their respective host nations. The Japanese minority from Latin America, then, was a minority even in the internment camps.

Japanese-American infantrymen of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team hike up a muddy French road in the Chambois Sector, France, in late 1944. In 1943 President Roosevelt suggested to the War Department that Japanese-Americans join the U.S. Army in an all-Japanese-American unit as one means to prove the loyalty of the Japanese-American community. This unit became known as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and demonstrated great bravery and skill. About 3,000 men from Hawaii and 800 men from the mainland served in the armed forces at the time the unit was formed.

Italian, German and Japanese residents of Latin America leaving a temporary internment camp in the Panama Canal Zone to join their male relatives in U.S. internment camps. April 7, 1942. Toward the end of the war the War Relocation Authority asked all internees over the age of 18—this time including Japanese from Peru—if they were loyal to the United States, and would defend the country against Japan if called upon to do so. Many of the Issei (first generation immigrants), who had been denied American citizenship because of their race, agonized at the prospect of facing parents, friends, and relatives in Japan at gunpoint. However, if they refused to declare loyalty to America they could become stateless. Some second generation Nisei, too, were suspicious of a government that had taken away their rights as American citizens. Not surprisingly, Japanese Peruvians, whose only American experience was their internment, were equally, if not more, hostile. By 1943, after many Japanese Americans had proved loyal to the US by enlisting, the US began drafting Japanese-American men including those who had been denied most of the rights enjoyed by US citizens and been imprisoned. As a result, by the end of the war more than 33,000 Japanese-American men and women had served in the American armed forces. The West Coast exclusion orders that had barred Japanese Americans from living on the coast were terminated in December, 1944, and the last camp was closed in March 1946. Although no provisions were made to compensate them for the losses they incurred during the war or as a result of internment (except for the $25 that each was given when leaving the camps), Japanese-Americans were free to go anywhere in the country. Many returned to the West Coast. But Japanese-Peruvians who were detained in the United States were neither allowed to return to Peru until 1948. Nor were their belongings returned to them by the Peruvian government following return. Although a few managed to return to Latin America, many were either deported to Japan or reentered the United States from Mexico and applied for a visa to stay in the United States. In 1988, over 110,000 Japanese Americans who were interned during the war received an official apology from the American government and $20,000 compensation for being incarcerated. However, Japanese Latin Americans who were interned received no apology or compensation. This was because when they were deported from Peru, their passports were taken away by the Peruvian government, and they were classified as "illegal aliens" upon their arrival in the States. Being neither U.S. citizens nor permanent residents at that time, they failed to qualify for reparations even though the majority eventually became American citizens after the war. Finally, after a class-action lawsuit, in June 1998 American-interned Latin Americans received an official apology from the U.S. government and nominal compensation of $5000. However, only about 800 Latin Americans accepted this offer, the others simply rejecting it outright. As mentioned, in summer 2007 a US Senate committee formed a commission to investigate the relocation, internment, and deportation of Latin Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. It estimated that the cost of the investigation would be about $500,000. The sponsors included Senators Daniel Inouye and Daniel Akaka from Hawaii, Ted Stevens and Lisa Murkowski from Alaska, Carl Levin from Michigan, Patrick Leahy from Vermont, and Congressmen, Xavier Becerra, Dan Lungren, and Mike Honda of California and Chris Cannon of Utah. The investigation was originally initiated in 2006 by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Latin Americans of Japanese Descent Act. It remains to be seen if the commission will come up with a solution that is acceptable to both the US government and the Latin American Japanese victims.

World War II

There were around 26,000 immigrants of Japanese nationality in Peru in 1941, the year of the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor, marking the beginning of the Pacific war campaign for the United States of America in World War II.[12] After the Japanese air raids on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, the U.S Office of Strategic Services (OSS), formed during World War II to coordinate secret espionage activities against the Axis Powers for the branches of the United States Armed Forces and the United States State Department, were alarmed at the large Japanese Peruvian community living in Peru, and were also wary of the increasing new arrivals of Japanese nationals to Peru.

Fearing the Empire of Japan could sooner or later decide to invade the Republic of Peru and use the southern American country as a landing base for its troops, and its nationals living there as foreign agents against America, in order to open another military front in the American Pacific, the U.S. government quickly negotiated with Lima a political-military alliance agreement in 1942; 1,799[12]

This political-military alliance provided Peru with new military technology such as military aircraft, tanks, modern infantry equipment, and new boats for the Peruvian Navy, as well as new American bank loans and new investments in the Peruvian economy.

In return, the Americans ordered the Peruvians to track, identify and create ID files for all the Japanese Peruvians living in Peru. Later, at the end of 1942 and during all of 1943 and 1944, the Peruvian government on behalf of the U.S. Government and the OSS organized and started the massive arrests, without warrants and without judicial proceedings or hearings, and the deportation of almost all the Japanese Peruvian community to several American internment camps run by the U.S. Justice Department in the states of Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Georgia and Virginia.[13]

The enormous groups of Japanese Peruvian forced exiles were initially placed amongst the Japanese-Americans who had been excluded from the US west coast; later they were interned in the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) facilities in Crystal City, Texas; Kenedy, Texas; and Santa Fe, New Mexico[14] The Japanese-Peruvians were kept in these "alien detention camps" for more than two years before, through the efforts of civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins,[12][15] being offered "parole" relocation to the labor-starved farming community in Seabrook, New Jersey.[16] The interned Japanese Peruvian nisei in the United States were further separated from the issei, in part because of distance between the internment camps and in part because the interned nisei knew almost nothing about their parents' homeland and language.[17]

The deportation of Japanese Peruvians to the United States also involved expropriation without compensation of their property and other assets in Peru.[18] At war's end, only 79 Japanese Peruvian citizens returned to Peru, and about 400 remained in the United States as "stateless" refugees.[19] The interned Peruvian nisei who became naturalized American citizens would consider their children sansei, meaning three generations from the grandparents who had left Japan for Peru.[20]

Japanese-Peruvians in the post-war period

Alberto Fujimori (first president of Japanese origins)

Although anti-Japanese discrimination in Peru was among the worst in Latin America, in 1990 Alberto Fujimori was elected President, and was reelected in 1995. He was the first person not only of Japanese descent, but of Asian descent, to be elected president outside Asia after Cheddi Jagan of Guyana. In late 2000 Fujimori’s administration was rocked by scandal, and accusations of corruption and human rights violations. While Fujimori was visiting Japan, the Peruvian authorities indicted him. Fujimori’s resignation was announced while he was in Japan. Receiving a faxed resignation letter, the Peruvian Congress refused to accept his resignation, and instead removed him from office. It then barred him from holding any elective office for 10 years and the Congress requested the Japanese government to deport Fujimori to Peru for investigation of his crimes.

While Japan was negotiating his relocation, in spite of the 10-year ban, in 2005 Fujimori sought to run in the presidential election of 2006, but the Peruvian authorities officially disqualified him. After traveling to Chile in 2005, Fujimori was detained by the Chilean authorities. He was released from prison in 2006 but placed under house arrest. The Peruvian government formally requested extradition to face human rights and corruption charges, but the Chilean government rejected the request in 2007 (his extradition is still being decided in the courts). In summer 2007, Fujimori tried to run for a seat in Japan’s Upper House. Running under the banner of the small People’s New Party, he called himself “the last samurai” in campaign videos, and pledged to restore traditional values to government. His 51,411 votes fell far short of winning. These political incidents seem to have set back social progress for people of Japanese descent in Peru.

Dekasegi Japanese-Peruvians

In the 1980s, the Peruvian economy suffered a number of setbacks, and inflation soared as high as 2000% a year at times. In Japan, however, with the economic boom many factories were short of labor. Around this period, the average wage for an unskilled laborer in Japan was about $20,000 per year (Tsuda 1999: 693). This was over 40 times the minimum wage in Peru, and over eight times the salary of many in management.[5] These economic conditions led many people from Peru to seek work in Japan.

Japanese companies in the 1980s hesitated to hire people of different ethnic backgrounds. It was felt that such people might not adapt well to Japanese labor practices. The Japanese government proposed avoiding some of these problems by employing Nikkei (people of Japanese descent born and raised outside Japan) returnees from Latin America, who, it was thought, shared racial and cultural affinities with Japanese. The government issued special work permits to people of Japanese descent going back three generations. These guest workers are commonly called dekasegi[6] (lit. “migratory earners”) workers in Japan. The results were not quite those anticipated. In the case of Peru, in 1992 Victor Aritomi, the Peruvian ambassador to Japan, said that although it was reported that among the almost 40,000 Japanese-Peruvians—that is, half of the Japanese-Peruvian population—who were then living in Japan, only 15,000 at most were “real” Japanese descendants. The rest—that is, almost two thirds of the “Japanese-Peruvians” in Japan at the time—not only had no primordial tie with Japan, but many did not even “look” particularly Asian.

Part of the reason for this was that many dekasegi workers of Japanese descent in Peru had non-Japanese spouses. Since the Japanese government had issued work permits to nuclear family members of dekasegi workers in 1990, the actual composition of the group was not limited to people of Japanese descent. According to Yanagida (1997: 297), about 30% of Nikkei couples in Peru with a spouse of Latin American origin had dekasegi experiences in 1995. This compares with only 9% of couples in which both partners were Nikkei who had dekasegi experiences at that time. Hearing of the high wages in Japan, many non-Nikkei Peruvians also wished to go to Japan to work. These non-Nikkei people used one of three strategies to obtain dekasegi work permits: (1) become a spouse of a Nikkei, (2) become an adopted child of a Nikkei family, or (3) become Nikkei through use of false or spurious documents—usually Japanese koseki (the Japanese registration of one’s birth and parentage). According to a Spanish correspondent in Tokyo, Montse Watkins, her non-Nikkei Peruvian interviewees paid between one and three thousand US dollars to “become” an adopted child of a Nikkei Peruvian (Watkins 1994: 112, 131, 135). The price of adoption differed depending on the family; however several thousand dollars seems to have been common.

In 1990 one municipal office of a township in Lima received 2,000 adoption registration documents and 500 marriage certificates—including one woman who adopted 60 children in one year (Watkins 1994: 131). Though it is obvious what is going on, the mayor claims that there is no way to stop these irregularities as these Nikkei are not breaking the law: they are free to adopt children or marry who they wish. Even selling and purchasing old koseki birth documents (say, at auction) is not illegal: antique dealers or collectors may simply wish to buy old documents, or papers from a foreign nation written in a foreign language (Fuchigami 1995: 26). Some people who newly and successfully became Nikkei in this way went to Japan to work. Others, however, have been swindled; criminals take their money but never produce the promised documents.

One social issue centers around the “Nikkei-ness” of members of Japanese-Peruvian society. Due to racial discrimination in Peru, some people of Japanese-descent left the Japanese-Peruvian community and assimilated in Peruvian society (Aoki 1997: 96). However, others have remained, worked hard for over a century to maintain Nikkei culture and society, and strived to be both model citizens of Peru and good Japanese.

In 1998 With New strict laws from the Japanese immigration many fake-nikkei were deported or went back to Peru. and The requirements to bring Japanese descendents were more strict including documents as "zairyuushikaku-ninteisyoumeisyo" [21] or Certificate of Eligibility for Resident that probes the Japanese blood line of the applicant.

With the onset of the global recession, Among the expatriate communities in Japan, Peruvians accounted for the smallest share of those who returned to their homelands after the global recession began in 2008. People returning from Japan also made up the smallest share of those applying for assistance under the new law. As of the end of November 2013, only three Peruvians who had returned from Japan had received reintegration assistance. The law provides some attractive benefits, but most Peruvians (At present 2015, there are 60,000 Peruvians in Japan )[22] who have regular jobs in Japan weren’t interested in going home.

Peruvians in Japan have come together to offer support for Japanese victims of the devastating earthquake and tsunami that struck in March 2011. In the wake of that disaster, the town of Minamisanriku in Miyagi Prefecture lost all but two of its fishing vessels. Peruvians raised money to buy the town new boats as a service to Japan and to express their gratitude for the hospitality received in Japan.[23]

The Japanese press in Peru

In 1909 Nipponjin (The Japanese people) was founded, a handwritten newspaper edited by someone with the surname Seki, who was a graduate of the University of Waseda, and who, as a free immigrant, worked at the Cerro de Pasco Corporation in La Oroya. The newspaper appeared about four times. It was written on sulfite paper or “office paper,” which was similar to the wrapping paper used in small businesses. The edition consisted of only one copy of thirty to forty pages that was held together by a string that served as a fastener of sorts.

Between 1910 and 1913, when 2473 Japanese arrived in Peru, there appeared another handwritten newspaper that was printed and distributed on mimeograph paper: Jiritsu (The Independent), whose format was 18x23 centimeters with each edition averaging some seventy-two pages, which also were fastened together with a string. Its printing on mimeograph made it possible for greater distribution than its predecessor. It ended in 1913, the same year that the emperor Taisho, grandfather of the current Japanese emperor, celebrated one year on the throne.

In June 1921, Nippi Shimpo (Japanese-Peruvian News) was published by Jutaro Tanaka, Teisuke Okubo, Noboru Kitahara, Kohei Mitsumori and Chijiwa.

January 1, 1929, Perú Nichi Nichi Shimbun (Daily News of Peru), with the goal of taking part in the debate. It was understood that the Japanese readership should neither be polarized nor silent witnesses in the polemic that had sustained the other two newspapers. This new publication was directed by Susumu Sakuray.

Jutaro Tanaka, one of the publishers of Nippi Shimpo, managed to merge three newspapers and publish Lima Nippo (Daily Bulletin of Lima). He argued that for such a small community it was not necessary to waste such efforts publishing three newspapers; rather, it was better to save supplies and offer the readership one good newspaper. This is how the newspaper was born in July 1929; Tanaka himself was named manager of the new company, and Sakuray, the former manager of Andes Jiho and Perú Nichi Nichi Shimbun, was named editor.

In 1929 Peru Jiho (Chronicles of Peru), began to circulate in the city, and it was supported by those who had opposed the merger of the original three newspapers. Kuninosuke Yamamoto assumed the leadership for two years, and in 1931, it passed to Hisao Ikeyama, a graduate of the University of Tokyo, who, thanks to his editorials that made the newspaper competitive, managed to stamp his own personal seal on the newspaper. Thereafter, a portion of the paper was published in Spanish, while some of the first Peruvians of Japanese descent worked on the newspaper, including Víctor Tateishi, Luis Okamoto, Julio Matsumura, Alberto Mochizuki, Enrique Shibao and Chihito Saito.

In July 1941, Susumu Sakuray, who had earlier left the paper Lima Nippo, published the Peru Hochi (Reports of Peru), which now brought the number of newspapers circulating in the community back to three. It was World War II, and there was great interest in getting the most recent news coming out of Europe and then Asia. However, when Japan became involved in the war and Peru declared war against Japan, the Peruvian government closed down and confiscated Japanese newspapers. The government also deported the major players in the Japanese community, including those Japanese who had become Peruvian citizens, as well as Peruvians of Japanese descent.

For almost a decade there were no Japanese-language newspapers circulating in Peru until July 1, 1950, when Peru Shimpo (Recent News from Peru) appeared, which remains in circulation today, and whose publication was authorized by Ministerial Resolution 107 of July 1, 1948. Peru Shimpo, just like Andes Jiho in 1913, was a product of donations gathered from among the members of the Japanese community. The organization for fundraising, as well as the donations lasted two years. With the proceeds the editors purchased machinery and the necessary typography, both of which arrived in Peru in February 1950. Diro Hasegawa was elected president of the board of directors, Masao Sawada as manager and Hiromu Sakuray as administrator and translator. The head of workshop was Kaname Ito, while some of the writers were Junji Kimura, Giei Higa, and Chihito Saito. Saito was also in charge of the Spanish section of the newspaper.

After a year in circulation, Peru Shimpo Press acquired office space in Lima downtown. At the end of the 1990s, the Japanese philanthropist, Ryoichi Jinnai, donated to the press a second-hand offset machine that remains in use today. At the start of the new century, the press relocated to Bellavista, Callao. The publication was printed in the standard format and had four pages. In the beginning moveable type characterized the process. Later, the publication increased to eight pages. In 2006 a new design system was introduced along with color pages and in 2010 Peru Shimpo became a tabloid. In 2006 Peru Shimpo modernized its design and introduced color. Alan García, the president of Peru, sent prepared remarks to the Nikkei community that was published there.

On October 1, 1955, which is to say, five years after the start date of Peru Shimpo, a second Japanese newspaper appeared in the post-war era: Peru Asahi Shimbun (Morning in Peru). Ryoko Kiyohiro was in charge of editing the Japanese sections and Víctor Hayashi the Spanish ones. The newspaper circulated until March 1964 when it shut down due to financial problems.

Prensa Nikkei (Nikkei Press) appeared in 1985 and remains as the only Spanish-language tabloid in circulation.

Notable people

- Koichi Aparicio: Peruvian footballer

- Ernesto Arakaki: International footballer

- Yasubey Enomoto: MMA fighter

- Alberto Fujimori: Agronomist, former university rector, former President of the Republic, prison inmate convicted of murder, bodily harm, and two cases of kidnapping

- Keiko Fujimori: Former First Lady, Congresswoman and businesswoman (daughter of Alberto Fujimori)

- Kenji Fujimori: Congressman (son of Alberto Fujimori)

- Santiago Fujimori: Lawyer (younger brother of Alberto Fujimori)

- Víctor García Toma: Former Minister of Justice

- Susana Higuchi: Politician, former First Lady, ex-spouse of Alberto Fujimori

- Jorge Hirano: International footballer

- Fernando Iwasaki: Writer

- Marco Miyashiro: Former General of Peru's National Police. He captured terrorists.

- Aldo Miyashiro: Writer, TV-Host & celebrity

- Augusto Miyashiro: Mayor of the City of Chorrillos since 1999, an important middle class southern suburban district of Metropolitan Lima

- Kaoru Morioka: Japanese futsal

- Venancio Shinki: Artist

- Arturo Yamasaki: referee, famous for the match between Italy and West Germany at 1970

- David Soria Yoshinari: International footballer

- Akio Tamashiro: Karate athlete. Pan American Gold medalist. Head of the Peruvian Karate Federation

- Eduardo Tokeshi: Plastic artist

- Tilsa Tsuchiya: Artist

- José Watanabe: Poet

- Rafael Yamashiro: Peruvian Congressman and politician

- Cesar Ychikawa: Singer & economist

- Jaime Yoshiyama: Former Prime Minister, former Cabinet Minister, former Vice President and former President of the Peruvian Congress

- Carlos Yushimito (Yoshimitsu): Writer & analyst

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- 1 2 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- ↑ Embassy of Peru in Japan

- ↑ Peruvian Japanese NewsPaper PeruShimpo

- ↑ Masterson, Daniel et al. (2004). The Japanese in Latin America: The Asian American Experience, p. 237., p. 237, at Google Books

- ↑ Lama, Abraham. "Home is Where the Heartbreak Is," Asia Times.October 16, 1999.

- 1 2 Palm, Hugo. "Desafíos que nos acercan," El Comercio (Lima, Peru). March 12, 2008.

- 1 2 Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), Japan: Japan-Peru relations (Japanese)

- ↑ "First Emigration Ship to Peru: Sakura Maru," Seascope (NYK newsletter). No. 157, July 2000.

- ↑ Irie, Toraji. "History of the Japanese Migration to Peru," Hispanic American Historical Review. 31:3, 437-452 (August–November 1951); 31:4, 648-664 (no. 4).

- ↑ Higashide, Seiichi. (2000). Adios to Tears, p. 218., p. 218, at Google Books

- ↑ "リマ日本人学校の概要" (Archive). Asociación Academia de Cultura Japonesa. Retrieved on October 25, 2015. "Calle Las Clivias(Antes Calle"A") No.276, Urb. Pampas de Santa Teresa, Surco, LIMA-PERU (ペルー国リマ市スルコ区パンパス・デ・サンタテレサ町クリヴィアス通り276番地)"

- 1 2 3 Densho, Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. "Japanese Latin Americans," c. 2003, accessed 12 Apr 2009.

- ↑ Robinson, Greg. (2001). By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans, p. 264., p. 264, at Google Books

- ↑ Higashide, pp. 157-158., p. 157, at Google Books

- ↑ "Japanese Americans, the Civil Rights Movement and Beyond" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ↑ Higashide, p. 161., p. 161, at Google Books

- ↑ Higashide, p. 219., p. 219, at Google Books

- ↑ Barnhart, Edward N. "Japanese Internees from Peru," Pacific Historical Review. 31:2, 169-178 (May 1962).

- ↑ Riley, Karen Lea. (2002). Schools Behind Barbed Wire: The Untold Story of Wartime Internment and the Children of Arrested Enemy Aliens, p. 10., p. 10, at Google Books

- ↑ Higashide, p. 222., p. 222, at Google Books

- ↑

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign affairs of Japan

- ↑ Your Doorway to Japan

References

- Connell, Thomas. (2002). America's Japanese Hostages: The US Plan For A Japanese Free Hemisphere. Westport: Praeger-Greenwood. ISBN 9780275975357; OCLC 606835431

- Gardiner, Clinton Harvey. (1975). The Japanese and Peru. 1873-1973. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0391-2; OCLC 2047887

- Gardiner, C. Harvey. (1981). Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295958552; OCLC 164799077

- Higashide, Seiichi. (2000). Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295979143 ISBN 9780295979144; OCLC 247923540

- López-Calvo, Ignacio. (2009). One World Periphery Reads the Other. Knowing the 'Oriental' in the Americas and the Iberian Peninsula. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009. 130-47. ISBN 9781443816571 ISBN 1443816574; OCLC 473479607

- Masterson, Daniel M. and Sayaka Funada-Classen. (2004), The Japanese in Latin America: The Asian American Experience. (View at Google Books) Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07144-7; OCLC 253466232