José Guadalupe Posada

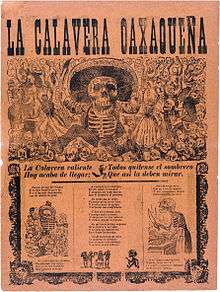

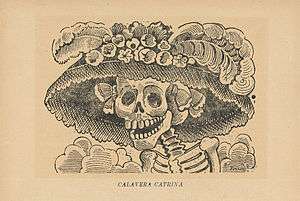

José Guadalupe Posada (February 2, 1852 – January 20, 1913[1]) was a Mexican political printmaker and engraver whose work has influenced many Latin American artists and cartoonists because of its satirical acuteness and social engagement. He used skulls, calaveras, and skeletons to make political and cultural critiques. Among his famous works was La Catrina.

Early life and education

Posada was born in Aguascalientes on February 2, 1852. His father was Germán Posada Serna and his mother Petra Aguilar Portillo.[2] Posada was one of eight children, among them; José Maria de la Concepción, José Cirilo, José Barbara, José Guadalupe, Ciriaco, and Maria Porfirio. His education in his early years was drawn from his older brother Cirilo, a country school teacher, who taught him reading, writing and drawing. He then joined la Academia Municipal de Dibujo de Aguascalientes (the Municipal Drawing Academy of Aguascalientes).[3] Later, in 1868, as a young teenager he went to work in the workshop of Trinidad Pedroso, who taught him lithography and engraving. Some of his first political cartoons were published in El Jicote, a newspaper that opposed Jesús Gómez Portugal.[4] He began his career as an artist making drawings, copying religious images and assisting in a ceramic workshop.

In 1872, Posada and Pedroza dedicated themselves to commercial lithography in Leon, Guanajuato.[5] While in Leon, Posada opened his own workshop and worked as a teacher of lithography at the School of Secondary education along with continuing his work with lithographs and wood engravings. In 1873, he returned to his home in Aguascalientes where married María de Jesús Vela in 1875. The following year he purchased the printing press from Trinidad Pedroza.[6] From 1875-1888, he continued to collaborate with several newspapers in León, including La Gacetilla, el Pueblo Caótico and La education.[7] He survived the great flood of León on June 18, 1888; of which he published several lithographs representing the tragedy in which more than two hundred and fifty corpses were found and more than 1,400 people were reported missing.[8] At the end of 1888, he moved to Mexico City, where he learned the craft and technique of engraving in lead and zinc. He collaborated with the newspaper La Patria Ilustrada and the Revisita de Mexico until the early months of 1890.[9]

He began to work with Antonio Vanessa Arroyo,[10] until he was able to establish his own lithographic workshop. From then on Posada undertook work that earned him popular acceptance and admiration, for his sense of humor, and propensity concerning the quality of his work.[11] In his broad and varied work, Posada portrayed beliefs, daily lifestyles of popular groups,[12] the abuses of government and the exploitation of the common people. He illustrated the famous skulls, along with other illustrations that became popular as they were distributed to various newspapers and periodicals.[13]

In spite of his varied and popular work, Posada was not as recognized as other contemporary artists. It wasn't until his death that his aesthetic as a true folk artist was recognized. This was largely thanks to Diego Rivera, who gave great publicity to his work.

Career as artist

In 1871, before he was out of his teens, his career began with a job as the political cartoonist for a local newspaper in Aguascalientes, El Jicote ("The Bumblebee"). The newspaper closed after 11 issues, reputedly because one of Posada's cartoons had offended a powerful local politician.[14] He then moved to the nearby city of León, Guanajuato. There Posada was married to Maria de Jesús Vela on September 20, 1875. In Leon, a former associate of his from Aguascalientes assisted him in starting a printing and commercial illustration shop. They focused on commercial and advertising work, book illustrations, and the printing of posters and other representations of historical and religious figures. Included among these figures were the Virgin of Guadalupe, the Virgin, the Holy Child of Atocha and Saint Sebastian.

In 1883, following his success, he was hired as a teacher of lithography at the local Preparatory School. The shop flourished until 1888 when a disastrous flood hit the city. He subsequently moved to Mexico City. His first regular employment in the capital was with La Patria Ilustrada, whose editor was Ireneo Paz, the grandfather of the later famed writer Octavio Paz. He later joined the staff of a publishing firm owned by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo and while at this firm he created a prolific number of book covers and illustrations. Much of his work was also published in sensationalistic broadsides depicting various current events.

From the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 until his death in 1913, Posada worked tirelessly in the press. The works he completed in his press during this time allowed him to develop his artistic prowess as a draftsman, engraver and lithographer. At the time he continued to make satirical illustrations and cartoons featured in the magazine, El Jicote. He played a crucial role for the government during the presidency of Francisco I Madero and during the campaign of Emiliano Zapata.[15]

He illustrated stories of crime and passion, along with stories of appearances and miracles. Posada portrayed and illustrated all kinds of characters in his works; some of them being revolutionaries, politicians, drunks, elegant ladies, bull fighters, workers and a wide array of others. He also coined the illustration for the famous skulls. They portrayed a wide variety of people, generally used to show the regrets and joys of the people.[16]

Notable works

Posada's best known works are his calaveras, which often assume various costumes, such as the Calavera de la Catrina, the "Skull of the Female Dandy", which was meant to satirize the life of the upper classes during the reign of Porfirio Díaz. Most of his imagery was meant to make a religious or satirical point. Since his death, however, his images have become associated with the Mexican holiday Día de los Muertos, the "Day of the Dead".

Later life

Largely forgotten by the end of his life, Posada's engravings were brought to a wider audience in the 1920s by the French artist Jean Charlot, who encountered them while visiting Diego Rivera. While Posada died in poverty, his images are well known today as examples of folk art. The muralist José Clemente Orozco knew Posada when he was young, and would look at him work through a window on the way to school, and credited Posada's work as an influence on his own.

Further reading

- Ades, Dawn, Art in Latin America: The Modern Era, New Haven, (Yale University Press), 1989, pp. 354, 110-123.

- Art Encyclopedia, Vol 25, p. 321.

- Catlin, Stanton, Art of Latin America Since Independence, New Haven, (Yale University Press, 1966), p. 190.

- Frank, Patrick, Posada's Broadsheets: Mexican Popular Imagery 1890-1910 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998).

- Montes i Bradley, Ricardo Ernesto, "Nuevo y valioso aporte al conocimiento de Posada”, Novedades. Mexico. D.F. May 4. 1952. The essay is an introduction to a publication containing 134 engravings by José Guadalupe Posada.[17]

- Posada, José Guadalupe, Posada’s Popular Mexican Prints, NY, (Dover Publications, 1972)

- Rothenstein, Julian, Posada: Messenger of Mortality, NY, (Moyer Ltd, 1989)

- Tenenbaum, Barbara, Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, New York, (Scribner’s, 1996), p. 457, Vol 14.

- Tyler, Ron, ed., Posada’s Mexico, Washington, (Library of Congress, 1979)

References

- ↑ Nick Caistor, Mexico City: A Cultural and Literary Companion (Interlink Books, 2000)p115

- ↑ "José Guadalupe Posada". Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre (in Spanish). 2016-11-01.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 37. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 38. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 49. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 50. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 52–57. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 64–70. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 70–76. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 105. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 110. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael. Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. 2009: Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 111–112. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ Barajas, Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 113. ISBN 9786071600752.

- ↑ History of Mexico - Mexico's Daumier: Josejhg Guadalupe Posada, by Jim Tuck in Mexico Connect

- ↑ "Fondo de Cultura Económica". www.fondodeculturaeconomica.com. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- ↑ Translated from Spanish (Jose Guadalupe Posada) Wiki Article

- ↑ Flores Villela, Carlos Arturo. "México, la cultura. el arte y la vida cotidiana. Vol 1". Serie Fuentes 7. p. 213. Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Humanidades. Universidad Autónoma de México.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to José Guadalupe Posada. |

- Print collection and information

- José Guadalupe Posada at the University of New Mexico

- Mexico's Daumier: José Guadalupe Posada

- José Guadalupe Posada: My Mexico, a traveling exhibit

- Posada - Mexico Connect

- Vanegas Arroyo-Posada Film Documentary Information

- Collection of José Guadalupe Posada Etchings and Broadsides at Artspawn

- TEDx Posada Lecture on YouTube

- Brady Nikas collection and information

- American Museum of Ceramic Art: Tribute to Jose Guadalupe Posada's La Catrina

- José Guadalupe Posada prints, 1880-1943