International law

International law is the set of rules generally regarded and accepted as binding in relations between states and between nations.[1][2] It serves as a framework for the practice of stable and organized international relations.[3] International law differs from state-based legal systems in that it is primarily applicable to countries rather than to private citizens. National law may become international law when treaties delegate national jurisdiction to supranational tribunals such as the European Court of Human Rights or the International Criminal Court. Treaties such as the Geneva Conventions may require national law to conform to respective parts.

Much of international law is consent-based governance. This means that a state member is not obliged to abide by this type of international law, unless it has expressly consented to a particular course of conduct.[4] This is an issue of state sovereignty. However, other aspects of international law are not consent-based but still are obligatory upon state and non-state actors such as customary international law and peremptory norms (jus cogens).

Terminology

The term "international law" can refer to three distinct legal disciplines:

- Public international law, which governs the relationship between states and international entities. It includes these legal fields: treaty law, law of sea, international criminal law, the laws of war or international humanitarian law, international human rights law, and refugee law.[5]

- Private international law, or conflict of laws, which addresses the questions of (1) which jurisdiction may hear a case, and (2) the law concerning which jurisdiction applies to the issues in the case.

- Supranational law or the law of supranational organizations, which concerns regional agreements where the laws of nation states may be held inapplicable when conflicting with a supranational legal system when that nation has a treaty obligation to a supranational collective.

Branches

The two traditional branches of international law are:

- jus gentium – law of nations

- jus inter gentes – agreements between nations.

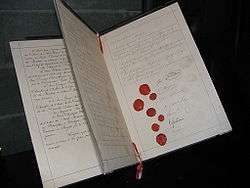

History

The modern study of international law starts in the early 19th century, but its origins go back at least to the 16th century, and Alberico Gentili, Francisco de Vitoria and Hugo Grotius, the "fathers of international law."[7] Several legal systems developed in Europe, including the codified systems of continental European states and English common law, based on decisions by judges and not by written codes. Other areas developed differing legal systems, with the Chinese legal tradition dating back more than four thousand years, although at the end of the 19th century, there was still no written code for civil proceedings.[8] Some doubt the effectiveness of international law, as they see the implementation of international law as a policy option among others to tackle global dilemmas.[9] They say that international law must be evaluated with other, possibly more effective, international law options.[10]

Sources of international law

International law is sourced from decision makers and researchers looking to verify the substantive legal rule governing a legal dispute or academic discourse. The sources of international law applied by the community of nations to find the content of international law are listed under Article 38.1 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice: Treaties, customs, and general principles are stated as the three primary sources; and judicial decisions and scholarly writings are expressly designated as the subsidiary sources of international law. Many scholars agree that the fact that the sources are arranged sequentially in the Article 38 of the ICJ Statute suggests an implicit hierarchy of sources.[11] However, there is no concrete evidence, in the decisions of the international courts and tribunals, to support such strict hierarchy, at least when it is about choosing international customs and treaties. In addition, unlike the Article 21 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which clearly defines hierarchy of applicable law (or sources of international law), the language of the Article 38 do not explicitly support hierarchy of sources.

The sources have been influenced by a range of political and legal theories. During the 20th century, it was recognized by legal positivists that a sovereign state could limit its authority to act by consenting to an agreement according to the principle pacta sunt servanda. This consensual view of international law was reflected in the 1920 Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice, which was succeeded by the United Nations Charter and is preserved in the United Nations Article 7 of the 1946 Statute of the International Court of Justice.[12]

Types of international law

Public international law

Public international law (or international public law) concerns the treaty relationships between the nations and persons which are considered the subjects of international law. Norms of international law have their source in either:

- custom, or customary international law (consistent state practice accompanied by opinio juris),[13]

- globally accepted standards of behavior (peremptory norms known as jus cogens or ius cogens), or

- codifications contained in conventional agreements, generally termed treaties.

Article 13 of the United Nations Charter obligates the UN General Assembly to initiate studies and make recommendations which encourage the progressive development of international law and its codification. Evidence of consensus or state practice can sometimes be derived from intergovernmental resolutions or academic and expert legal opinions (sometimes collectively termed soft law).

Private international law

Conflict of laws, often called "private international law" in civil law jurisdictions, is distinguished from public international law because it governs conflicts between private persons rather than states (or other international bodies with standing). It concerns the questions of which jurisdiction should be permitted to hear a legal dispute between private parties, and which jurisdiction's law should be applied, therefore raising issues of international law. Today corporations are increasingly capable of shifting capital and labor supply chains across borders, as well as trading with overseas corporations. This increases the number of disputes of an inter-state nature outside a unified legal framework, and raises issues of the enforceability of standard practices. Increasing numbers of businesses use commercial arbitration under the New York Convention 1958.

Supranational law

Systems of "supranational law" arise when nations explicitly cede their right to make certain judicial decisions to a common tribunal.[14] The decisions of the common tribunal are directly effective in each party nation, and have priority over decisions taken by national courts.[15] The European Union is an example of an international treaty organization which implements a supranational legal framework, with the European Court of Justice having supremacy over all member-nation courts in matter of European Union law.

International courts

There are numerous international bodies created by treaties adjudicating on legal issues where they may have jurisdiction. The only one claiming universal jurisdiction is the United Nations Security Council. Others are: the United Nations International Court of Justice, and the International Criminal Court (when national systems have totally failed and the Treaty of Rome is applicable) and the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

East Africa Community

There were ambitions to make the East African Community, consisting of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda, a political federation with its own form of binding supranational law, but this effort has not materialized.

Union of South American Nations

The Union of South American Nations serves the South American continent. It intends to establish a framework akin to the European Union by the end of 2019. It is envisaged to have its own passport and currency, and limit barriers to trade.

Andean Community of Nations

The Andean Community of Nations is the first attempt to integrate the countries of the Andes Mountains in South America. It started with the Cartagena Agreement of 26 May 1969, and consists of four countries: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. The Andean Community follows supranational laws, called Agreements, which are mandatory for these countries.

See also

- Centre for International Law (CIL)

- Commissions of the Danube River

- Comparative law

- Conference of the parties

- Global administrative law

- Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies

- International criminal law

- International Law Commission

- International legal theory

- International litigation

- Internationalization of the Danube River

- Law of war and International humanitarian law

- List of International Court of Justice cases

- Martens Clause

- Pacta sunt servanda (agreements are to be kept)

- Roerich Pact

- Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project (RULAC)

- Sources of international law

Notes and references

- ↑ "international law". Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ↑ The term was first used by Jeremy Bentham in his "Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation" in 1780. See Bentham, Jeremy (1789), An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, London: T. Payne, p. 6, retrieved 2012-12-05

- ↑ Slomanson, William (2011). Fundamental Perspectives on International Law. Boston, USA: Wadsworth. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Slomanson, William (2011). Fundamental Perspectives on International Law. Boston, USA: Wadsworth. p. 4.

- ↑ There is an ongoing debate on the relationship between different branches of international law. Koskenniemi, Marti (September 2002). "Fragmentation of International Law? Postmodern Anxieties". Leiden Journal of International Law. 15 (3): 553–579. doi:10.1017/S0922156502000262. Retrieved 30 January 2015. Yun, Seira (2014). "Breaking Imaginary Barriers: Obligations of Armed Non-State Actors Under General Human Rights Law – The Case of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child". Journal of International Humanitarian Legal Studies. 5 (1-2): 213–257. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ Pagden, Anthony (1991). Vitoria: Political Writings (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought). UK: Cambridge University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 0-521-36714-X.

- ↑ Thomas Woods Jr. (18 September 2012). How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Regnery Publishing, Incorporated, An Eagle Publishing Company. pp. 5, 141–142. ISBN 978-1-59698-328-1.

- ↑ China and Her People, Charles Denby, L. C. Page, Boston 1906 page 203

- ↑ S.J. Hoffman, J-A. Røttingen, J. Frenk. 2012. “The Economics of New International Health Laws,” The Lancet 380: S4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60290-1.

- ↑ S.J. Hoffman, J-A. Røttingen. 2011. “A Framework Convention on Obesity Control?” The Lancet 378(9809): 2068. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61894-1.

- ↑ Slomanson, William (2011). Fundamental Perspectives on International Law. Boston, USA: Wadsworth. pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Charter of the United Nations, United Nations, 24 October 1945, 1 UNTS, XVI

- ↑ Druzin; Druzin. "Law Without the State: The Theory Of High Engagement and the Emergence of Spontaneous Legal Order within Commercial Systems". Georgetown Journal of International Law. 41: 606.

- ↑ Degan, Vladimir Đuro (1997-05-21). Sources of International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 9789041104212. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Blanpain, Roger (2010). Comparative Labour Law and Industrial Relations in Industrialized Market Economies. Kluwer Law International. pp. 410 n.61. ISBN 9789041133489. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

Bibliography

- I Brownlie, Principles of Public International Law (OUP 2008)

- World Encyclopedia of Law, with International Legal Research and a Law dictionary

Further reading

- Anaya, S.J. (2004). Indigenous Peoples in International Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517350-5.

- Klabbers, J. (2013). International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19487-7.

- Shaw, M.N. (2014). International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-06127-5.

External links

| Library resources about International law |

- UN International Law

- United Nations Rule of Law, the United Nations' centralised website on the rule of law

- UNOG Library Legal Research Guide

- Centre for International Law (CIL), Singapore

- International law overview

- Department of International Law, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva

- Primary Legal Documents Critical to an Understanding of the Development of Public International Law

- Public International Law as a Form of Private Ordering