Eagle (heraldry)

The eagle is used in heraldry as a charge, as a supporter, and as a crest. Sometimes just the headless body ("sans head" eagle) or the head replaced with another symbol, as well as parts of the eagle, such as its head, wing or leg, are used as a charge or crest.

The eagle with its keen eyes symbolized perspicacity, courage, strength and immortality, but is also considered "king of the skies" and messenger of the highest gods. With these attributed qualities the eagle became a symbol of power and strength in Ancient Rome. Mythologically, it has been connected by the Greeks with the God Zeus, by the Romans with Jupiter, by the Germanic tribes with Odin, by the Judeo-Christian scriptures with those who hope in God (Isaiah 40:31), and in Christian art with Saint John the Evangelist.

Symbolism

The eagle as a symbol has a history much longer than that of heraldry itself. In Ancient Egypt, the falcon was the symbol of Horus, and in Roman polytheism of Jupiter. An eagle appears on the battle standard of Cyrus the Great in Persia, around 540 BC. The eagle as a "heraldic animal" of the Roman Republic was introduced in 102 BC by consul Gaius Marius. According to Islamic tradition, the Black Standard of Muhammad was known as راية العُقاب rāyat al-`uqāb "banner of the eagle" (even though it did not depict an eagle and was solid black). In Christian symbolism the four living creatures of scripture (a man, an ox, a lion, and an eagle) have traditionally been associated with the Four Evangelists. The eagle is the symbol of Saint John the Evangelist.

In medieval and modern heraldry eagles are often said to indicate that the armiger (person bearing the arms) was courageous, a man of action and judicious. Where an eagle's wings were spread ("displayed") it was said to indicate the bearer's role as a protector.

In the same way that a lion is considered the king of beasts, the eagle is regarded as the pre-eminent bird in heraldry. It has been more widely used and more highly regarded in Continental European heraldry than in English heraldry. For instance, in the roll of Henry III of England (reigned 1216–1272) there are only three eagles.

Depiction

![]() Media related to examples of heraldic eagles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to examples of heraldic eagles at Wikimedia Commons

The depiction of the heraldic eagle is subject to a great range of variation in style. The eagle was far more common in continental European—particularly German—than English heraldry, and it most frequently appears Sable (colored black) with its beak and claws Or (colored gold or yellow). It is often depicted membered (having limbs of a different color than the body) / armed (an animal depicted with its natural weapons of a different color than the body) and langued (depicted having a tongue of a different color than the body) gules (colored red), that is, with red claws / talons and tongue. In its relatively few instances in Gallo-British heraldry, the outermost feathers are typically longer and point upward.

Parts

Head

An eagle can appear either single- or double-headed (bicapitate). On at least one occasion a three-headed (tricapitate) eagle is seen.[1]

Recursant describes an eagle with his head turned to the sinister (left side of the field). In full aspect describes an eagle with his head facing the onlooker. In trian aspect (a rare, later 16th and 17th century heraldry term) describes when the eagle's head is facing at a three-quarter view to give the appearance of depth – with the head cocked at an angle somewhere between profile and straight-on.

Wings

Overture or close is when the wings are shown at the sides and close to the body, always depicted statant (standing in profile and facing the right side of the field). (Trussed - the term when depicting domestic or game birds with their wings closed - is not used because the eagle is a proud animal and the word implies it is tied up or bound by a net.)

Addorsed ("back to back") is when the eagle is shown statant (standing in profile and facing the right side of the field) and ready to fly, with the wings shown open behind the eagle so that they almost touch.

Espanie or épandre ("expanded") is when the eagle is shown affronté (facing the viewer with the head turned to the dexter) and the wings are shown with the tips upward.

Abaisé ("lowered") is when the eagle is shown affronté (facing the viewer) and the wings are shown with the tips downward. A good example is the eagle on the reverse side of the US quarter dollar coin.

Klee-Stengeln ("clover-stems") are the pair of long-stemmed trefoil-type charges on the wings of 13th-century German depictions of the heraldic eagle. They represent the upper edge of the wings and are normally Or (yellow), like the beak and claws. Reinmar von Zweter fashioned the Klee-Stengeln of his eagle into a second and third head.[2]

Attitudes (positions)

There is a debate over whether rousant or displayed is the eagle's default depiction. Displayed is more common because it is more artistically pleasing and it fully uses the field's space. Displayed also predates the use of rousant, with examples going back to the early Middle Ages.

There is also sometimes confusion between a rousant eagle with displayed wings and a displayed eagle. The difference is that rousant eagles face to the right and have their feet on the ground and displayed eagles face the viewer, have their legs splayed out, and the tail is completely visible.

Eagle rousant

An eagle rising or rousant is preparing to fly, but its feet are still on the ground. It is the eagle's version of statant (standing in profile and facing the right side of the field).

- with wings addorsed and elevated means in profile with the wings swept to the back and their tips extended upwards.

- with wings addorsed and inverted means in profile with wings swept to the back and their tips extended downwards.

- with wings displayed and elevated means facing to the front with the wings spread and their tips extended upwards.

- with wings displayed and inverted means facing to the front with the wings spread and their tips extended downwards.

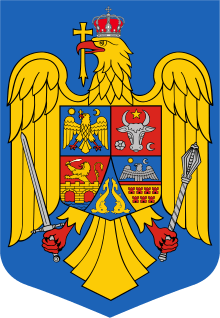

Eagle displayed

The informal term "spread eagle" is derived from a heraldic depiction of an eagle displayed (i.e. upright with both wings, both legs, and tailfeathers all outstretched). The wings are usually depicted "expanded" or "elevated" (i.e., with the points upward); displayed inverted is when the wings are depicted points downward. According to Hugh Clark, An Introduction to Heraldry, the term spread eagle refers to "an eagle with two heads, displayed",[3] but this distinction has apparently been lost in modern usage. Most of the eagles used as emblems of various monarchs and states are displayed, including those on the coats of arms of Germany, Poland, Romania, and the United States.

Eagle volant

Volant describes an eagle in profile shown in flight with wings shown addorsed and elevated and its legs together and tucked under. It is considered in bend ("diagonal") as it is flying from the lower sinister (heraldic left, from the shield-holder's point of view) to the upper dexter (heraldic right, from the shield-holder's point of view) of the field. However, the term "in bend" is not used unless a bend is actually on the field.

Eagles combatant

Like the heraldic lion, the heraldic eagle is seen as dominating the field and normally cannot brook a rival. When two eagles are depicted on a field, they are usually shown combatant, that is, facing each other with wings spread and one claw extended, as though they were fighting. Respectant, the term used for depicting domestic or game animals shown facing each other, is not used because eagles are aggressive predators.

Eagles addorsed

When two eagles are shown back-to-back and facing the edges of the field the term used is addorsed / endorsed or adossés ("back-to-back").

Variants

Eaglet

This term is used when three or more Eagles are shown on a field. They represent immature Eagles.

Alerion

Originally the term Erne or Alerion in early Heraldry referred to a regular Eagle. Later heralds used the term Alerion to depict baby Eagles. To differentiate them from mature Eagles, Alerions were shown as an Eagle Displayed Inverted without a beak or claws (disarmed). To difference it from a decapitate (headless) eagle, the Alerion has a bulb-shaped head with an eye staring towards the Dexter (right-hand side) of the field. This was later simplified in modern heraldry as an abstract winged oval.

An example is the arms of the Duchy of Lorraine (Or, on a Bend Gules, 3 Alerions Abaisé Argent). It supposedly had been inspired by the assumed arms of crusader Geoffrey de Bouillon, who supposedly killed three white eaglets with a bow and arrow when out hunting.[4] It is far more likely to be Canting arms that are a pun based on Lorraine / Erne.

Imperial Eagle

Roman Empire

The Aquila was the eagle standard of a Roman legion, carried by a special grade legionary known as an Aquilifer. One eagle standard was carried by each legion. Pliny the Elder (H.N. x.16) enumerates five animals displayed on Roman military ensigns: the eagle, the wolf, the minotaur,[5] the horse, and the boar. In the second consulship of Gaius Marius (104 BC) the four quadrupeds were laid aside as standards, the eagle being alone retained. It was made of silver, or bronze, with outstretched wings, but was probably of a relatively small size, since a standard-bearer (signifer) under Julius Caesar is said in circumstances of danger to have wrenched the eagle from its staff and concealed it in the folds of his girdle.[6] Under the later emperors the eagle was carried with the legion, a legion being on that account sometimes called aquila (Hirt. Bell. Hisp. 30). Each cohort had for its own ensign the serpent or dragon, which was woven on a square piece of cloth textilis anguis,[7] elevated on a gilt staff, to which a cross-bar was adapted for the purpose,[8] and carried by the draconarius.[9]

Eastern imperial eagles

The double-headed eagle became the symbol of the Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos. Palaiologos recaptured Constantinople from the Crusaders in 1261 and adopted the double-headed eagle as his symbol of the dynasty's interests in both Asia and Europe. It represented looking towards the East (Asia Minor, traditional power center of the Byzantine-government in exile after the IVth Crusade) and the West (newly reconquered land in Europe) centered on Constantinople. The Byzantine double-headed eagle has been seen in late 13th century, certainly pre-dating the development of the same in western heraldry.

In Russia it was Ivan III of Russia who first assumed the two-headed eagle, when, in 1472, he married Sophia, daughter of Thomas Palæologus, and niece of Constantine XI, the last Emperor of Byzantium. The two heads symbolised the Eastern or Byzantine Empire and the Western or Roman Empire.

The Empire of Trebizond (1204–1461), one of the states created after the capture of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade, used the emblem of the normal (single headed) eagle. The black eagle on yellow background is still used today in Greece by descendants of Pontian Greeks.[10]

Holy Roman Empire

Charlemagne, a Frankish ruler and the first Holy Roman Emperor, died in 814, centuries before the introduction of heraldry. In later periods, a coat of arms attributed to Charlemagne shows half of the body of a single-head black eagle as the symbol of the German emperors next to a fleur-de-lis as the symbol of the kings of France on an impaled shield.

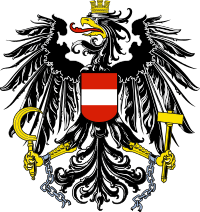

According to Carl-Alexander von Volborth the first instance of the use of an eagle as an heraldic charge is the Great Seal of the Margrave Leopold IV of Austria in 1136, which depicts him carrying a shield charged with an eagle. Also from about this time is a coin showing a single-headed eagle,[11] minted in Maastricht (the Netherlands), dating from between 1172 and 1190 after contacts with the East via the Crusades. One Gilbert d'Aquila was granted Baronetcy of Pevensey by William after the Battle of Hastings. The family who held Pevensey castle and the newly formed Borough of Pevensey used the eagle symbol in the 11th century.

From the reign of Frederick Barbarossa in 1155 the single-headed eagle became a symbol of the Holy Roman Empire. The eagle was clearly derived from the Roman eagle and continues to be important in the heraldry of those areas once within the Holy Roman Empire. Within Germany the placement of one's arms in front of an eagle was indicative of princely rank under the Holy Roman Empire. The first mention of a double-headed eagle in the West dates from 1250 in a roll of arms of Matthew Paris for Emperor Frederick II.

French Empire

.svg.png)

The French Imperial Eagle or Aigle de drapeau (lit. "flag eagle") was a figure of an eagle on a staff carried into battle as a standard by the Grande Armée of Napoleon I during the Napoleonic Wars.

Although they were presented with Regimental Colours, the regiments of Napoleon I tended to carry at their head the Imperial Eagle. This was the bronze sculpture of an eagle weighing 1.85 kg (4 lb), mounted on top of the blue regimental flagpole. They were made from six separately cast pieces and, when assembled, measured 310 mm (12 in) in height and 255 mm (10 in) in width. On the base would be the regiment's number or, in the case of the Guard, Garde Impériale. The eagle bore the same significance to French Imperial regiments as the colours did to British regiments - to lose the eagle would bring shame to the regiment, who had pledged to defend it to the death.

Upon Napoleon's fall, the restored monarchy of Louis XVIII of France ordered all eagles to be destroyed and only a very small number escaped. When the former emperor returned to power in 1815 (known as the Hundred Days) he immediately had more eagles produced, although the quality did not match the originals. The workmanship was of a lesser quality and the main distinguishing changes had the new models with closed beaks and they were set in a more crouched posture.

Napoleon also used the French Imperial Eagle in the heraldry of the First Empire, as did his nephew Napoleon III during the Second Empire. An eagle remains in the arms of the House of Bonaparte and the current royal house of Sweden retains the French Imperial Eagle on its dinastic inescutcheon, as his founder, Jean Bernadotte, was Marshal of France.

Eagle of Saint John

John the Evangelist, the author of the fourth gospel account, is symbolized by an eagle, often with a halo, an animal may have originally been seen as the king of the birds. The eagle is a figure of the sky, and believed by Christian scholars to be able to look straight into the sun.[12]

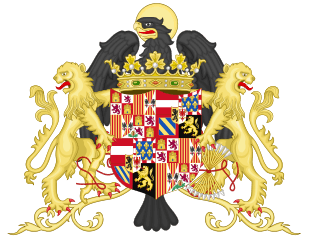

The better known heraldic use of the Eagle of St. John has been the single supporter chose by Queen Isabella of Castile in her armorial achievement used as heiress and later integrated into the heraldry of the Catholic Monarchs. This election alludes to the queen's great devotion to the evangelist that predated her accession to the throne.[13] There is a magnificent tapestry with the armorial achievement of the Catholic Monarchs in the Throne Room of the Alcazar of Segovia.[14]

The Eagle of St. John was placed on side of the shields used as English consort by Catherine of Aragon, daughter of the Catholic Monarchs, Mary I and King Philip as English monarchs. In Spain, Philip bore the Eagle of St John (single or two figures depending versions) in his ornamented armorial achievements until 1668.[15]

The Eagle of the Evangelist was recovered as single supporter holding the 1939, 1945 and 1977 official models of the armorial achievement of Spain[16] and it has been removed in 1981 when the current was adopted.[17] The use of the eagle of St. John was exploited by the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who used it as a symbol of his regime.

Prominent examples of the use of St. John's Eagle in heraldry across the world include the heraldry or emblems of: Valparaíso City (Chile); Boyacá Department (Colombia); Catholic Archdiocese of Besançon (France); Mallersdorf-Pfaffenberg (Germany); Lima City (Peru); Kisielice, Kwidzyn District and county, Oleśnica Town and county (Poland); Gata (Spain); and the St. John's College (University of Sydney, Australia).

Coat of arms used by Isabella of Castile as heiress

Coat of arms used by Isabella of Castile as heiress.svg.png) Coat of arms of the Catholic Monarchs

Coat of arms of the Catholic Monarchs Ornamented coat of arms of Queen Joanna of Castile

Ornamented coat of arms of Queen Joanna of Castile Coat of arms of Catherine of Aragon as Queen of England

Coat of arms of Catherine of Aragon as Queen of England.svg.png) Coat of arms of Queen Mary I of England

Coat of arms of Queen Mary I of England.svg.png)

.svg.png) Ornamented coat of arms of Philip II of Spain

Ornamented coat of arms of Philip II of Spain

(1558–1580).svg.png) One of the versions of the national coat of arms of Spain used from 1938/1939 to 1981

One of the versions of the national coat of arms of Spain used from 1938/1939 to 1981

Modern usage

United Kingdom

An eagle is present on the official emblem of the Royal Air Force

United States

Since 20 June 1782, the United States has used its national bird, the bald eagle, on its Great Seal; the choice was intended to at once recall the Roman Republic and be uniquely American (the bald eagle being indigenous to North America). The American Eagle has been a popular emblem throughout the life of the republic, with an eagle appearing in the flags and seals of the President, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, Justice Department, Defense Department, Postal Service, and other organizations, on various coins (such as the quarter dollar), and in various American corporate logos past and present, such as those of Case and American Eagle Outfitters.

Arab countries

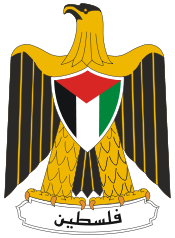

In Arab nationalism, with the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, the eagle became the symbol of revolutionary Egypt, and was subsequently adopted by several other Arab states (the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Libya, the partially recognised State of Palestine, and Yemen).

The eagle as a symbol of Saladin is disputed by archaeologists. The symbol of an eagle was found on the west wall of the Cairo Citadel (constructed by Saladin), and so is assumed by many to be his personal symbol. There is, however, little proof to defend this.

As a heraldic symbol identified with Arab nationalism, the Eagle of Saladin was subsequently adopted as the coats of arms of Iraq and Palestine. It has previously been the coat of arms of Libya, but later replaced by the Hawk of Quraish. The Hawk of Quraish was itself abandoned after the Libyan Civil War. The Eagle of Saladin was part of the coat of arms of South Yemen prior to that country's unification with North Yemen.

Examples

A wide variety of political entities across the world use an eagle in their official emblems. The variation among them is instructive, in that it reflects connections among various heraldic traditions. The following is just a sampling of these.

.svg.png)

Eagle decapitate (without head), coat of arms of German nobility von der Hoven alias Pampus

Eagle decapitate (without head), coat of arms of German nobility von der Hoven alias Pampus Eagle's body with Wolf head in the shield of Langenorla municipality, Germany

Eagle's body with Wolf head in the shield of Langenorla municipality, Germany Spanish Arrano beltza

Spanish Arrano beltza The national flag of Kazakhstan has a gold sun with 32 rays above a soaring golden steppe eagle

The national flag of Kazakhstan has a gold sun with 32 rays above a soaring golden steppe eagle Emblem of the Sri Lanka Air Force

Emblem of the Sri Lanka Air Force

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ granted in 1957 to Waiblingen (kreis) The three heads symbolise the three former territories that were transformed into the district.

- ↑ Reinmar von Zweter's peculiar eagle is famously depicted in the Codex Manesse.

- ↑ Clark, Hugh (1892). An Introduction to Heraldry, 18th ed. (Revised by J. R. Planché). London: George Bell & Sons. First published 1775. ISBN 1-4325-3999-X

- ↑ Rothery, Guy Cadogan. Concise Encyclopedia of Heraldry. pp.50

- ↑ See Festuson the Minotaur.

- ↑ Flor. iv.12

- ↑ Sidon. Apoll. Carm. v.409

- ↑ Themist. Orat. i. p1, xviii. p267, ed. Dindorf; Claudian, iv. Cons. Honor. 546; vi. Cons. Honor. 566

- ↑ Veget. de Re Mil. ii.13; compare Tac. Ann. i.18

- ↑ Eleni Kokkonis-Lambropoulos & Katerina Korres-Zografos (1997). Greek flags, arms and insignia (Ελληνικές Σημαίες, Σήματα-Εμβλήματα) (in Greek). E. Kokkonis-G. Tsiveriotis. p. 52. ISBN 960-7795-01-6.

- ↑ Deutsche Wappen - GERMAN NATIONAL ARMS

- ↑ Emile Male, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, p 35–7, English trans. of 3rd edn, 1913, Collins, London (and many other editions), ISBN 978-0064300322

- ↑ VV. AA., Isabel la Católica en la Real Academia de la Historia, Real Academia de la Historia, 2004. ISBN 978-84-95983-54-1. Cfr. para la heráldica de Isabel y Fernando las [https://books.google.com/books?id=AN3PWOdZ5SEC&lpg=PA63&pg=PA72#v=onepage&q&f=false pp. 72 & ff.

- ↑ Image of the Thron Room of the Alcázar of Segovia.

- ↑ Francisco Olmos, José María de. Las primeras acuñaciones del príncipe Felipe de España (1554-1556): Soberano de Milán Nápoles e Inglaterra, pp. 158-162.

- ↑ Menéndez Pidal y Navascués, Faustino; O'Donnell y Duque de Estrada, Hugo; Lolo, Begoña (1999). Símbolos de España [The Symbols of Spain]. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. p. 255. ISBN 84-259-1074-9.

- ↑ Act 33/1981, 5 October (BOE No 250, 19 October 1981). Coat of arms of Spain (Spanish).

Bibliography

- Fox-Davies, A.C.; A Complete Guide to Heraldry, Bloomsbury Books, London, 1985

- Puttock, Colonel A.G.; Heraldry in Australia, Child & Associated Publishing Pty. Ltd. Frenchs Forest, 1988

- Volborth, Carl-Alexander von; Heraldry, Customs, Rules and Styles, New Orchard Editions, Poole, 1981

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eagles in heraldry. |

- The Arms of Byzantium

- Birds of prey in Early Greek Art

- Arthurian Heraldry

- Fleur-de-lis designs

- A Glossary of Terms used in Heraldry by James Parker

- International Civic Heraldry

- Pimbley's Dictionary of Heraldry – E

- QM Web (Quartermaster Museum)

- Russian College of Heraldry