Howard Florey

| The Lord Florey OM FRS FRCP | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Howard Walter Florey 24 September 1898 Adelaide, South Australia |

| Died |

21 February 1968 (aged 69) Oxford, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Fields | Bacteriology, immunology |

| Institutions |

University of Adelaide University of Oxford University of Cambridge University of Sheffield |

| Alma mater |

University of Adelaide Magdalen College, Oxford |

| Known for | Discovery of penicillin's properties |

| Influences | Charles Sherrington[1] |

| Notable awards |

Nobel Prize in Physiology Fellow of the Royal Society (1941)[2] or Medicine (1945) Lister Medal (1945)[3] Knight Bachelor Albert Medal (1946) Royal Medal (1951) Copley Medal (1957) Lomonosov Gold Medal (1965) Wilhelm Exner Medal (1960) |

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey, OM, FRS, FRCP (24 September 1898 – 21 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Sir Ernst Boris Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his role in the development of penicillin.

Although Fleming received most of the credit for the discovery of penicillin, it was Florey who carried out the first ever clinical trials in 1941 of penicillin at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford on the first patient, a postmaster from Wolvercote near Oxford. The patient started to recover but subsequently died because Florey was unable, at that time, to make enough penicillin. It was Florey and Chain who actually made a useful and effective drug out of penicillin, after the task had been abandoned as too difficult.

Florey's discoveries, along with Alexander Fleming and Ernst Chain, are estimated to have saved over 82 million lives,[4] and he is consequently regarded by the Australian scientific and medical community as one of its greatest figures. Sir Robert Menzies, Australia's longest-serving Prime Minister, said, "In terms of world well-being, Florey was the most important man ever born in Australia".[5]

Early life and education

Howard Florey was the youngest of three children and the only son.[6] His father, Joseph Florey, was an English immigrant, and his mother Bertha Mary Florey was a third-generation Australian.[7] He was born in Adelaide, South Australia, in 1898.

Florey was educated at Kyre College Preparatory School (now Scotch College) and then St Peter's College, Adelaide, where he was a brilliant academic and junior sportsman. He studied medicine at the University of Adelaide from 1917 to 1921. At the university, he met Ethel Reed (Mary Ethel Hayter Reed), another medical student, who became both his wife and his research colleague. The marriage was unhappy, due to Ethel's poor health and Florey's intolerance.[8]

Florey continued his studies at Magdalen College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, receiving the degrees of BA and MA. In 1926, he was elected to a fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and a year later he received the degree of PhD from the University of Cambridge.

Career

After periods in the United States and at Cambridge, Florey was appointed to the Joseph Hunter Chair of Pathology at the University of Sheffield in 1931. In 1935 he returned to Oxford, as Professor of Pathology and Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford, leading a team of researchers. In 1938, working with Ernst Boris Chain and Norman Heatley, he read Alexander Fleming's paper discussing the antibacterial effects of Penicillium notatum mould.

In 1941, he and Chain treated their first patient, Albert Alexander, who had had a small sore at that corner of his mouth, which then spread leading to a severe facial infection involving Streptococci and Staphylococci.[9] His whole face, eyes and scalp were swollen to the extent that he had had an eye removed to relieve some of the pain. Within a day of being given penicillin, he started recovering. However, the researchers did not have enough penicillin to help him to a full recovery, and he relapsed and died. Because of this experience and of the difficulty in producing penicillin, the researchers changed their focus to children, who could be treated with smaller quantities.

Florey's research team investigated the large-scale production of the mould and efficient extraction of the active ingredient, succeeding to the point where, by 1945, penicillin production was an industrial process for the Allies in World War II. However, Florey said that the project was originally driven by scientific interests, and that the medicinal discovery was a bonus:

People sometimes think that I and the others worked on penicillin because we were interested in suffering humanity. I don't think it ever crossed our minds about suffering humanity. This was an interesting scientific exercise, and because it was of some use in medicine is very gratifying, but this was not the reason that we started working on it.— Howard Florey, [10]

Developing penicillin was a team effort, as these things tend to be— Howard Florey, Baron Florey

Florey shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Ernst Boris Chain and Alexander Fleming. Fleming first observed the antibiotic properties of the mould that makes penicillin, but it was Chain and Florey who developed it into a useful treatment.[11]

Honours and awards

On 18 July 1944 Florey was appointed a Knight Bachelor.[12][13] In 1947 he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine.[14]

He was awarded the Lister Medal in 1945 for his contributions to surgical science.[3] The corresponding Lister Oration, given at the Royal College of Surgeons of England later that year, was titled "Use of Micro-organisms for Therapeutic Purposes".[15]

Florey was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1941 and became president in 1958.[2] In 1962, Florey became Provost of The Queen's College, Oxford. During his term as Provost, the college built a new residential block, named the Florey Building in his honour. The building was designed by the British architect Sir James Stirling.

On 4 February 1965 Sir Howard was appointed a life peer and became Baron Florey, of Adelaide in the State of South Australia and Commonwealth of Australia and of Marston in the County of Oxford.[16] This was a higher honour than the knighthood awarded to penicillin's discoverer, Sir Alexander Fleming, and it recognised the monumental work Florey did in making penicillin available in sufficient quantities to save millions of lives in the war, despite Fleming's doubts that this was feasible. On 15 July 1965 Florey was appointed a Member of The Order of Merit.[17]

Florey was Chancellor of the Australian National University from 1965 until his death in 1968. The lecture theatre at the John Curtin School of Medical Research was named for him during his tenure at the ANU.

Posthumous honours

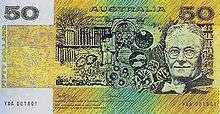

Florey's portrait appeared on the Australian $50 note for 22 years (1973–95), and the suburb of Florey in the Australian Capital Territory is named after him. The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, located at the University of Melbourne, Victoria, and the largest lecture theatre in the University of Adelaide's medical school are also named after him. In 2006, the federal government of Australia renamed the Australian Student Prize, given to outstanding high-school leavers, the "Lord Florey Student Prize", in recognition of Florey.

The Florey Unit [18] of the Royal Berkshire Hospital in Reading, Berkshire, is named after him.

The "Lord Florey Chair" in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Sheffield is named in his honour.

Personal life

After the death of his wife Ethel, he married in 1967 his long-time colleague and research assistant Margaret Jennings (1904-1994). He died of a heart attack in 1968 and was honoured with a memorial service at Westminster Abbey, London.

On his religious views, Florey was an agnostic.[19]

In popular culture

"Breaking the Mould" is a 2009 historical drama that tells the story of the development of penicillin in the 1930s/40's, by the group of scientists at Oxford headed by Florey at The Dunn School of Pathology. The film stars Dominic West (as Florey), Denis Lawson, and Oliver Dimsdale; directed by Peter Hoar and written by Kate Brooke.

References

- ↑ Todman, Donald (2008). "Howard Florey and research on the cerebral circulation". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. Elsevier. 15.

His mentor was the neurophysiologist and Nobel Laureate, Sir Charles Sherrington who directed him in neuroscience research. Florey’s initial studies on the cerebral circulation represent an original contribution to medical knowledge and highlight his remarkable scientific method. The mentorship and close personal relationship with Sherrington was a crucial factor in Florey’s early research career.

- 1 2 Abraham, E. P. (1971). "Howard Walter Florey. Baron Florey of Adelaide and Marston 1898-1968". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 17: 255–302. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1971.0011. PMID 11615426.

- 1 2 "Sir Howard Florey, F.R.S.: Lister Medallist". Nature. 155 (3942): 601. 1945. doi:10.1038/155601b0.

- ↑ Woodward, Billy. "Howard Florey-Over 6 million Lives Saved." Scientists Greater Than Einstein Fresno: Quill Driver Books, 2009 ISBN 1-884956-87-4.

- ↑ Fenner, Frank (1996). "Florey, Howard Walter (Baron Florey) (1898–1968)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. vol. 14. Melbourne University Press. pp. 188–190. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ P43 The Mold in Dr Flory's Coat by Eric Lax.

- ↑ V. Quirke, Howard Walter Florey

- ↑ Fenner, Frank. "Mary Ethel Hayter Florey". Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ MacFarlane, Gwyn (1979). "The proving of penicillin". Howard Florey : the making of a great scientist. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Pr. pp. 327–346. ISBN 9780198581611.

- ↑ Bright Sparcs – Australasian Science article: Howard Florey

- ↑ Judson, Horace Freeland (20 October 2003). "No Nobel Prize for Whining". The New York Times. NYTimes. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 36620. pp. 3415–3416. 21 July 1944.

- ↑ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1945. nobelprize.org

- ↑ Moore, George. The Creators.

- ↑ Florey, H. W. (1945). "Use of Micro-organisms for Therapeutic Purposes". BMJ. 2 (4427): 635–642. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4427.635. PMC 2060276

. PMID 20786386.

. PMID 20786386. - ↑ The London Gazette: no. 43571. p. 1373. 9 February 1965.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 43713. p. 6729. 16 July 1965.

- ↑ Sexual Health Department. royalberkshire.nhs.uk

- ↑ Trevor Illtyd Williams (1984). Howard Florey, Penicillin and After. Oxford University Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-19-858173-4.

As an agnostic, the chapel services meant nothing to Florey but, unlike some contemporary scientists, he was not aggressive in his disbelief.

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Cockcroft |

Chancellor of the Australian National University 1965 – 1968 |

Succeeded by H. C. Coombs |