History of the Jews in Sicily

The history of the Jews in Sicily deals with Jews and the Jewish community in Sicily which possibly dates back two millennia. Sicily is a large island off the Southern Italian coast. There has been a Jewish presence in Sicily for at least 1400 years and possibly for more than 2000 years.

Ancient history

There is a legend that Jews were first brought to Sicily as captive slaves in the 1st century after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE. However, it is generally presumed the Jewish population of Sicily was seeded prior to the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem. Rabbi Akiva visited the city of Syracuse during one of his trips abroad.[1]

Middle Ages

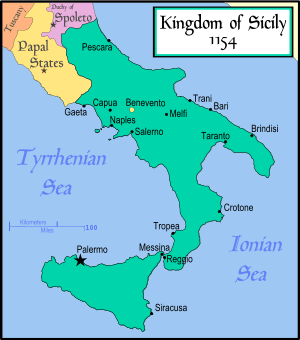

The Jews lived in many Sicilian cities such as Palermo,[2] Messina[3] and Catania.[4] From the late 7th century, Sicily joined with Calabria to form the Byzantine Theme of Sicily.[5] In the 6th century, communications were sent to Pope Gregory I about the plight of the Jews in the Kingdom of Sicily. In 831, Sicily came under the Arab dominion, who treated the Jews justly.[2]

In 1072, during the First Crusade, Sicily fell to the Normans; and the Jews were again brought under the supremacy and jurisdiction of the Catholic Church.[2] The Norman Kingdom of Sicily lasted until 1194, when it fell to the Hohenstaufens.[6] In 1210, the Jews of Sicily faced such persecution from the Crusaders that Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II had to intervene on their behalf. Persecution of the Jews continued. But, despite persecution, Sicilian Jews continued to thrive. Some Sicilian rabbis communicated with Maimonides posing religious questions.[1]

Systematic persecution of the Jews in Sicily started in the 14th century. In 1310 the King of Sicily Frederick II of Aragon adopted a restrictive and discriminatory policy towards the Jews, who were required to mark their clothes and their shops with the "red wheel". Jews were also forbidden any relationship with Catholics. In 1392, Jews were ordered to live in ghettos and severe persecutions broke out in Monte San Giuliano (now Erice), Catania and Syracuse, in which many Jews fell victim. The next year strict decrees were directed against private ceremonies. For example, Jews were forbidden to use any decorations in connection with funerals; except in unusual cases, when silk was permitted, the coffin might be covered with a woolen pall only. In Marsala, Jews were compelled to take part in the festival services at Christmas and on St. Stephen's Day, and were then followed home by the mob and stoned on the way. At the beginning of the 15th century oppression was at such a level that in 1402 the Jews of Marsala presented an appeal to the king, in which they asked for: (1) exemption from compulsory menial services; (2) the reduction of their taxes to one-eleventh of the total taxation, since the Jews were only one-eleventh of the population; (3) the hearing of their civil suits by the royal chief judge, and of their religious cases by the inquisitor; (4) the delivery of flags only to the superintendent of the royal castle, not to others; (5) the reopening of the women's bath, which had been closed under Andrea Chiaramonte. This appeal was granted.[7]

In comparison with other Jewish communities of Europe, the Sicilians were happily situated. They even owned a considerable amount of property, since thirteen of their communities were able, in 1413, to lend the infante Don Juan 437 ounces of gold. This was repaid on 24 December 1415. In the same year, however, the Jewish community of Vizzini was expelled by Queen Blanca, and it was never permitted to return.

The culmination of persecution came with the expulsion of Jews from Sicily. The decree of banishment dated 31 March 1492 was decreed by Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. At the time there were around 25.000-30.000 Jews living on the island, in 52 different locations.[7] On 9 June Jews were forbidden to depart secretly, sell their possessions, or conceal any property; on 18 June the carrying of weapons was prohibited; their valuables were appraised by royal officials on behalf of the state, packed in boxes, and given into the care of wealthy Catholics. On 13 August came the order to be ready to depart; the following articles might be taken: one dress, a mattress, a blanket of wool or serge, a pair of used sheets, a few provisions, besides three taros as traveling money. All other Jewish property was confiscated by the Crown. After numerous appeals, the date of departure was postponed to 18 December, and later, after a payment of 5,000 gulden, to 12 January 1493. The departure actually occurred on 31 December 1492.

The exiles found protection under Ferdinand I of Naples in Apulia, Calabria and Naples. On the death of Ferdinand in 1494, Charles VIII of France invaded Naples. At that time a serious disease, known as "French fly," broke out in that region, and the responsibility for the outbreak was fixed upon the Jews, who were accordingly driven out of the Kingdom of Naples. They then sought refuge in Turkish territory, and settled chiefly in Constantinople, Damascus, Salonica, and Cairo. To remain in Sicily, most of Sicily's Jewish population left the island. The remained of converted Jews were around 9.000.[8]

Language and culture

In the late ancient period the predominantly spoken language of the Jewish (and non-Jewish) population of Sicily has been the Greek language. When Greek was the main language in Jewish inscriptions, as was the case with Jewish inscriptions from Sicily, Greek names, which were locally common, appear in significant numbers in Jewish inscriptions.[9] Still after the Muslim conquest of the island, the use of the Greek language and the ties of the Sicilian Jews to the Byzantine Empire,[10] its economy and its Jewish communities continued to function under the new circumstances.[11][12] Through these Byzantine(-Jewish) connections, the Synagogue liturgy of the original Sicilian Jews, represented the Romaniote prayer rite.[13][14]

Modern times

In a proclamation of 3 February 1740, containing 37 paragraphs, Jews were formally invited to return to Sicily. A few came, but, feeling their lives insecure, they soon went back to Turkey.[7]

Rabbi Stefano Di Mauro, an Italian American descendant of southern Italian neofiti, has been active on the island and opened a small synagogue in 2008, but he has not yet set up a full-time Jewish congregation in Sicily.[15] In addition, Shavei Israel has expressed in interest in helping to facilitate the Sicilian Bnei Anusin back to Judaism.[16]

References

- 1 2 www.pjvoice.com

- 1 2 3 www.jewishencyclopedia.com

- ↑ http://www.morasha.it/zehut/mn01_espulmessina.html

- ↑ www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org

- ↑ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 1891–1892. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ↑ Dupont, Jerry (2001). The common law abroad: constitutional and legal legacy of the British empire. Wm. S. Hein Publishing. p. 793. ISBN 978-0-8377-3125-4.

- 1 2 3

- ↑

- ↑ Leonard Victor Rutgers, The Hidden Heritage of Diaspora Judaism. 1998

- ↑ Ember et al., Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World, p. 192-ff. 2004

- ↑ Joshua Holo, Byzantine Jewry in the Mediterranean Economy. 2009

- ↑ Bernard Spolsky, The Languages of the Jews: A Sociolinguistic History. 2014

- ↑ Joshua Holo, Byzantine Jewry in the Mediterranean Economy, p. 91-ff. 2009

- ↑ R. Langer, Cursing the Christians?: A History of the Birkat HaMinim, p. 203. 2012

- ↑ www.haaretz.com

- ↑ www.michaelfreund.org

External list

See also

- History of the Jews in Italy

- History of the Jews in Apulia

- History of the Jews in Calabria

- History of the Jews in Southern Central Italy

- History of the Jews in Livorno

- History of the Jews in Naples

- History of the Jews in the Roman Empire

- History of the Jews in San Marino

- History of the Jews in Trieste

- History of the Jews in Turin

- History of the Jews in Venice

- Haplogroup G2c (Y-DNA)