1st Fallschirm-Panzer Division Hermann Göring

| Fallschirm-Panzer-Division 1. Hermann Göring 1st Paratroop Panzer Division Hermann Göring | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1935–45 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Panzer/Fallschirmjäger |

| Size |

Regiment Brigade Division |

| Patron | Hermann Göring |

| Engagements |

World War II |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |

|

| Identification symbol | Divisional insignia |

The Fallschirm-Panzer-Division 1. Hermann Göring (1st Paratroop Panzer Division Hermann Göring - abbreviated Fallschirm-Panzer-Div 1 HG) was an elite German Luftwaffe armoured division. The HG saw action in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and on the Eastern Front. The division began as a battalion-sized police unit in 1933. Over time it grew into a regiment, brigade, division, and finally was combined with the Parachute-Panzer Division 2 Hermann Göring in 1944 to form a Panzer corps under the by then Reichsmarschall. It surrendered to the Soviet Army near Dresden on May 8, 1945.

Service history

With the Nazi seizure of 1933, Hermann Göring was appointed as Prussian Minister of the Interior. In this capacity, all Police units in Prussia came under Göring's control. On 24 February 1933, Göring authorized the creation of a police battalion. Working in conjunction with Göring's secret police, the Gestapo, the unit was involved in many attacks against Communists and Social democrats. In January 1934, under pressure from Hitler and Himmler, Göring gave Himmler's SS control of the Gestapo. To reinforce the position of his remaining unit, Göring increased its size and instituted a military training program. During the Night of the Long Knives, the unit and Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler executed many SA leaders, removing the formation as a threat to the NSDAP.

In 1935, Göring was promoted to command of the Luftwaffe and ordered the unit transferred to the Luftwaffe, renaming it Regiment General Göring in September 1935. Two sub-units were separated from the regiment in March 1938 and redesignated German 1st Parachute Division, the first of the Fallschirmjäger (airborne) units. In 1936, the regiment was assigned for Göring's bodyguards and as flak protection for Hitler's Headquarters. The regiment participated in the annexation of Austrian (Anschluss) and the invasion of the Occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1938, and then in March 1939. During Fall Gelb, this force took part in the invasion of the Netherlands and Belgium.

During Operation Barbarossa, the regiment was attached to the 11th Panzer Division, a part of Army Group South. The regiment saw action around the areas of Radziechów, Kiev and Bryansk. In July 1942 the regiment was upgraded to brigade status, and then to full division in October 1942 as a Panzer division. While the division was in formation, the Second Battle of El Alamein had forced Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps to retreat to Tunisia. The division was sent to Tunisia piecemeal, where it eventually surrendered with the rest of Panzer Army Africa.

The reformed division was designated Panzer Division Hermann Göring and sent to Sicily. After the Allied invasion of Sicily was launched on 10 July 1943, the division was engaged at the Amphibious Battle of Gela and the Battle of Centuripe, retreating to Messina afterwards. When the armistice between Italy and Allied armed forces was signed, the division took part in the Operation Achse to disarm Italian troops. The division participated in the fighting following the Allied landing at Salerno in Operation Avalanche on 9 September. It then retreated towards the Volturno–Termoli line, and then to the Gustav Line, where it was pulled out of the line for rest and refit.

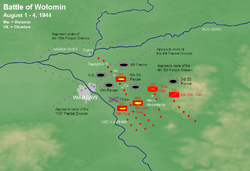

The Corps size Fallschirm-Panzerkorps Hermann Göring was created in 1944 through the combination of the unit with the Fallschirm-Panzergrenadier Division 2 Hermann Göring. After the start of the Allied offensive, Operation Diadem, on 12 May, the division retreated towards Rome and then abandoned the city. The division arrived in Poland in late-July and fought alongside SS Division Wiking and the 19th Panzer Division on the Vistula River between Modlin Fortress and Warsaw. In August, its counter-attack against the Magnaszew bridgehead, defended by the 8th Guards Army, failed after heavy fighting. Between August and September 1944, the division used captured Polish non-combatant civilians as human shields when attacking the insurgents' positions during the Warsaw uprising. Following the destruction of the town, the division was attached to the newly formed Army Group Vistula formed 24 January 1945, defending the ruins of Warsaw in what Hitler termed "Festung Warschau", or Fortress Warsaw. During the Vistula-Oder Offensive, much of the division was broken in battle.

In April, the remnants of the Hermann Göring Panzerkorps were sent to Silesia, and in heavy fighting were slowly pushed back into Saxony. On April 22, the Fallschirm-Panzer-Division 1. Hermann Göring was one of two divisions that broke through the inter-army boundary of the Polish 2nd Army (Polish People's Army or LWP) and the Soviet 52nd Army, in an action near Bautzen, destroying parts of their communications and logistics trains and severely damaging the Polish (LWP) 5th Infantry Division and 16th Tank Brigade before being stopped two days later.[1][2][3][4]

In early May, units of the corps attempted to break out towards the American forces on the Elbe, but were unsuccessful. The corps surrendered to the Red Army on 8 May 1945.

Alleged war crimes

According to a British Government report, the Hermann Göring Division was involved in several reprisal operations during its time in Italy. One of these occurred in the surrounding area of the village of Civitella in Val di Chiana on 6 June 1944 where 250 civilians were killed.[5]

Around 800 soldiers from the division took part in fighting during the August–October 1944 Warsaw Uprising in the Wola district, where mass executions of civilians occurred in connection with Hitler's orders to destroy the city. The units were:

- II./Fallschirm-Panzer-Regiment "Hermann Göring" (20 PzKpfw IV tanks)

- III./Fallschirm-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 2. "Hermann Göring"

- IV./Fallschirm-Panzer-Artillerie-Regiment "Hermann Göring"[6]

Polish sources claim soldiers of the Hermann Göring Division used civilians as human shields in front of its tanks while clearing barricades during the Warsaw ghetto uprising.

Commanders

- Major Walther von Axthelm, 13 August 1936 – 31 May 1940

- Oberst Paul Conrath, 1 June 1940 – 14 April 1944

- Generalmajor Wilhelm Schmalz, 16 April 1944 – 30 September 1944

- Generalmajor Hanns-Horst von Necker, 1 October 1944 – 8 February 1945

- Generalmajor Max Lemke, 9 February 1945 – 8 May 1945

Fallschirm-Panzer-Korps Hermann Göring

- Generalleutnant Wilhelm Schmalz, 4 October 1944 – 8 May 1945

Citations

- ↑ Erickson, John: "The Road to Berlin", page 591. Yale University Press, 1999.

- ↑ D. F. Ustinov et al.: "Geschichte des Zweiten Weltkrieges" (Volume 10), page 399. Militärverlag der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, 1979.

- ↑ von Ahlfen, Hans: "Der Kampf um Schlesien 1944/1945", pages 208-209. Motorbuch Verlag, 1977. v. Ahlfen quotes the April 27, 1945 war diary entry of Luftflottenkommando 6, noting that for all operations between Görlitz and Bautzen, involving multiple German divisions, during April 20–26, that the Soviet 94th Rifle Division was destroyed, and that the Soviet 7th Guards Mechanized Corps, the Soviet 254th Rifle Division, the Polish 1st Tank Corps (LWP), the Polish 16th Tank Brigade (LWP), and the Polish 5th, 7th, and 8th Infantry Divisions (LWP) took heavy losses. The war diary goes to state that 355 enemy tanks were destroyed, 320 enemy guns of all kinds were destroyed or captured, about 7,000 enemy dead were tallied, and that 800 prisoners were taken.

- ↑ Grzelak, Czesław et al.: "Armia Berlinga i Żymierskiego", pages 275 and 279. Wydawnictwo Neriton, 2002. As described here, after penetrating the inter-army boundary, the German attack struck the Polish 5th Infantry Division and 16th Tank Brigade (LWP) in the rear, practically destroying both units and killing the commanding general of the 5th Infantry Division. Losses for the Polish 2nd Army (LWP) in the area of Bautzen and Dresden are noted as approximately 5,000 KIA, 2,800 missing or taken prisoner, and 10,500 WIA. Overall the Polish 2nd Army lost 20 per cent of its personnel and material strength. Among these losses were 170 tanks, 56 self-propelled guns, 124 mortars, 232 guns of all calibers, 330 vehicles, and 1,373 horses.

- ↑ Michael Geyer:Es muß daher mit schnellen und drakonischen Maßnahmen durchgegriffen werden in: Hannes Heer, Klaus Neumann (Hrsg.): Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht. Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-930908-04-2, S.208ff.

- ↑ http://wilk.wpk.p.lodz.pl/~whatfor/niemcy%20_w_powstaniu_warszawskim.htm

- ^ Report of British War Crimes Section of Allied Force Headquarters on German Reprisals for Partisan Activities in Italy

- ^ Polish government page

- ^ Professor Peter K. Gessner State University of New York at Buffalo