Hans Memling

Hans Memling (also spelled Memlinc; c. 1430 – 11 August 1494) was a German painter who moved to Flanders and worked in the tradition of Early Netherlandish painting. He spent some time in the Brussels workshop of Rogier van der Weyden, and after van der Weyden's death in 1464, Memling was made a citizen of Bruges, where he became one of the leading artists, painting both portraits and diptychs for personal devotion and several large religious works, continuing the style he learned in his youth.

Life and works

Born in Seligenstadt,[2] near Frankfurt in the Middle Main region, Memling served his apprenticeship at Mainz or Cologne, and later worked in the Low Countries under Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1455–1460) in Brussels, Duchy of Brabant. He then worked at Bruges, County of Flanders by 1465.[2]

.jpg)

He may have been wounded at the Battle of Nancy (1477), sheltered and cured by the Hospitallers at Bruges and to show his gratitude he refused payment for a picture he had painted for them. Memling did paint for the Hospitallers in 1479 and 1480, and it is likely that he was known to the patrons of St John prior to the Battle of Nancy. In 1477, when he was believed dead, he was under contract to create an altarpiece for the gild-chapel of the booksellers of Bruges. This altarpiece, Scenes of the Passion of Christ, now in the Galleria Sabauda of Turin, is not inferior in any way to those of 1479 in the Hospital of St. John, which for their part are hardly less interesting as illustrative of the master's power than The Last Judgment, which since the 1470s, is in the National Museum, Gdańsk. Critical opinion has been generally unanimous in assigning this altarpiece to Memling. This is evidence that Memling was a resident of Bruges in 1473; for the Last Judgment was likely painted and sold to a merchant at Bruges, who shipped it there on board a vessel bound to the Mediterranean which was captured by Danzig privateer Paul Beneke in that very year. The purchase of his pictures by an agent of the Medici demonstrates that he had a considerable reputation.

The oldest allusions to pictures connected to Memling point to his relations with the Burgundian court, which was held in Brussels. The inventories of Margaret of Austria, drawn up in 1524, allude to a triptych of the God of Pity by Rogier van der Weyden, of which the wings containing angels were painted by "Master Hans". He may have been apprenticed to van der Weyden in Bruges, where he afterwards dwelt.

The clearest evidence of the connection of the two masters is that afforded by pictures, particularly an altarpiece, which has alternately been assigned to each of them, and which may be due to their joint labours. In this altarpiece, which is a triptych ordered for a patron of the house of Sforza, we find the style of van der Weyden in the central panel of the Crucifixion, and that of Memling in the episodes on the wings. Yet the whole piece was assigned to the former in the Zambeccari collection at Bologna, whilst it was attributed to the latter at the Middleton sale in London in 1872.

Memling's painting of the Baptist in the gallery of Munich (c. 1470) is the oldest form in which Memling's style is displayed. The subsequent Last Judgment in Gdańsk shows that Memling preserved the tradition of sacred art used earlier by Rogier van der Weyden in the Beaune Altarpiece.

Memling's portraits, in particular, were popular in Italy.[3] According to Paula Nuttall, Memling's distinctive contribution to portraiture was his use of landscape backgrounds, characterized by "a balanced counterpoint between top and bottom, foreground and background: the head offset by the neutral expanse of sky, and the neutral area of the shoulders enlivened by the landscape detail beyond".[4] Memling's portrait style influenced the work of numerous late-15th-century Italian painters,[5] and is evident in works such as Raphael's Portraits of Agnolo and Maddalena Doni.[6] He was popular with Italian customers as shown in the preference given to them by such purchasers as Cardinal Grimani and Cardinal Bembo at Venice, and the heads of the house of Medici at Florence.

Oil on oak panel, 22 x 15 cm (each wing) Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg

Memling's reputation was not confined to Italy or Flanders. The Madonna and Saints (which passed from the Duchatel collection to the Louvre), the Virgin and Child (painted for Sir John Donne and now at the National Gallery, London), and the four attributed portraits in the Uffizi Gallery of Florence (including the Portrait of Folco Portinari), show that his work was widely appreciated in the 16th century.

The Scenes from the Passion of Christ in the Galleria Sabauda of Turin and the Advent and Triumph of Christ in the Pinakothek of Munich are illustrations of the habit in Flanders art of representing a cycle of subjects on the different planes of a single picture, where a wide expanse of ground is covered with incidents from the Passion in the form common to the action of sacred plays.

Memling became sufficiently prosperous that his name appears on a list of the 875 richest citizens of Bruges who were obligatory subscribers to the loan raised by Maximilian I of Austria, to finance hostilities towards France in 1480.[7] Memling's name does not appear on subsequent subscription lists of this type, suggesting that his financial circumstances declined somewhat as a result of the economic crisis in Bruges during the 1480s.[8]

The masterpiece of Memling's later years, the Shrine of St Ursula in the museum of the hospital of Bruges, is fairly supposed to have been ordered and finished in 1480. The delicacy of finish in its miniature figures, the variety of its landscapes and costume, the marvellous patience with which its details are given, are all matters of enjoyment to the spectator. There is later work of the master in the St Christopher and Saints of 1484 in the academy, or the Newenhoven Madonna in the hospital of Bruges, or a large Crucifixion, with scenes from the Passion, of 1491 from the Lübeck Cathedral (Dom) of Lübeck, now in Lübeck's St. Annen Museum. Near the close of Memling's career he was increasingly supported by his workshop. The registers of the painters' guild at Bruges give the names of two apprentices who served their time with Memling and paid dues on admission to the guild in 1480 and 1486. These subordinates remained obscure.

He died in Bruges. The trustees of his will appeared before the court of wards at Bruges on 10 December 1495, and we gather from records of that date and place that Memling left behind several children and considerable property.

Passion Altarpiece/Polyptych (1491) in Lübeck

Passion Altarpiece/Polyptych (1491) in Lübeck

Critical opinion

Erwin Panofsky in his 1953 Early Netherlandish Painting (p. 347), says of Memling: "... while the Romantics and the Victorians considered his sweetness the very summit of Medieval art, we feel inclined to compare him to a composer such as Felix Mendelssohn: he occasionally enchants, never offends, and never overwhelms. His works give the impression of derivativeness ..."

Selected works

- Adam and Eve (c. 1485), oil on oak, 69.3 × 17.3 cm (each), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Adoration of the Magi (c. 1470), oil on wood, 96.4 × 147 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- St John Altarpiece (c. 1479), oil on wood, Old St. John's Hospital, Bruges

- Advent and Triumph of Christ (1480), oil on wood, 81 × 189 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

- Allegory with a Virgin (1479–80), oil on oak panel, 38.3 × 31.9 cm, Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris

- Angel Musicians (1480s), oil on wood, 165 × 230 cm (each panel)

- Annunciation (1467–70), oil on panels, 83.3 × 26.5 cm (each), Groeninge Museum, Bruges

- Bathsheba (1485), oil on wood, 191 × 84 cm, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

- Carrying the Cross, oil on oak, 58.2 × 27.5 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- Christ at the Column (1485–90), oil on oak panel, 58.8 × 34.3 cm (with original frame), Colección Mateu, Barcelona

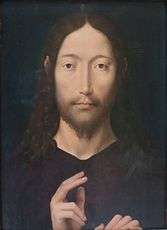

- Christ Giving His Blessing (1478), oil on oak panel, 38.1 × 28.2 cm, Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena

- Sibylla Sambetha (1480), oil on oak panel, 38 cm x 26.5 cm. Old St. John's Hospital, Bruges

- Christ Giving His Blessing (1481), oil on oak panel, 34.8 × 26.2 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Christ Surrounded by Musician Angels (1480s), oil on wood, 164 × 212 cm, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

- Crucifixion (detail), oil on oak, 56 × 63 cm (full panel), Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- Deposition (left wing of a diptych) (1490s), oil on oak panel, 538 × 39 cm, Groeninge Museum, Bruges

- Diptych of Jean de Cellier (c. 1475), oil on wood, 25 × 15 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

Gallery

Shrine of St. Ursula, 1489, Memlingmuseum, Sint-Janshospitaal, Bruges

Shrine of St. Ursula, 1489, Memlingmuseum, Sint-Janshospitaal, Bruges Christ Giving His Blessing, 1478, Norton Simon Museum

Christ Giving His Blessing, 1478, Norton Simon Museum Mater Dolorosa, c. 1480, Uffizi Gallery

Mater Dolorosa, c. 1480, Uffizi Gallery Christ Surrounded by Musician Angels, c. 1480 Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

Christ Surrounded by Musician Angels, c. 1480 Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp Mater Dolorosa, 1475

Mater Dolorosa, 1475- Annunciation, 1480–89, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Allegory with a Virgin, 1479–80

Allegory with a Virgin, 1479–80

- Portraits

Portrait of Gilles Joye, 1472

Portrait of Gilles Joye, 1472 Portrait of a Man with a Pink Carnation, 1475

Portrait of a Man with a Pink Carnation, 1475 Portrait of Maria Portinari, c. 1475

Portrait of Maria Portinari, c. 1475 Portrait of Willem Morell, c. 1480

Portrait of Willem Morell, c. 1480

Memling carpets

Memling carpets are a type of early Oriental carpet painted in several Memlings, and named after him. They are characterized by guls with "hooked" lines radiating from a central body, and probably came from Anatolia or Armenia.

References and sources

- References

- ↑ King, Donald and Sylvester, David eds. The Eastern Carpet in the Western World, From the 15th to the 17th century, p. 57, Arts Council of Great Britain, London, 1983, ISBN 0-7287-0362-9

- 1 2 Murray, P. and Murray, L. (1963) The Art of the Renaissance. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 156. ISBN 978-0-500-20008-7

- ↑ Borchert 2005, p. 70

- ↑ Borchert 2005, p. 74

- ↑ Borchert 2005, p. 78

- ↑ Borchert 2005, p. 83

- ↑ Borchert 2005, p. 15

- ↑ Borchert 2005, pp. 15–16

- Sources

- Borchert, Till-Holger (ed.) (2005). Memling's Portraits. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-09326-1.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- de Vos, Dirk (1994). Hans Memling: The Complete Works. Harry N Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3649-6.

External links

Media related to Hans Memling at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hans Memling at Wikimedia Commons- Petrus Christus: Renaissance master of Bruges

- Fifteenth- to eighteenth-century European paintings: France, Central Europe, the Netherlands, Spain, and Great Britain