Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension towards Europe, the North Atlantic Drift, is a powerful, warm, and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and stretches to the tip of Florida, and follows the eastern coastlines of the United States and Newfoundland before crossing the Atlantic Ocean. The process of western intensification causes the Gulf Stream to be a northward accelerating current off the east coast of North America. At about 40°0′N 30°0′W / 40.000°N 30.000°W, it splits in two, with the northern stream, the North Atlantic Drift, crossing to Northern Europe and the southern stream, the Canary Current, recirculating off West Africa.

The Gulf Stream influences the climate of the east coast of North America from Florida to Newfoundland, and the west coast of Europe. Although there has been recent debate, there is consensus that the climate of Western Europe and Northern Europe is warmer than it would otherwise be due to the North Atlantic drift which is the northeastern section of the Gulf Stream. It is part of the North Atlantic Gyre. Its presence has led to the development of strong cyclones of all types, both within the atmosphere and within the ocean. The Gulf Stream is also a significant potential source of renewable power generation. The Gulf Stream may be slowing down as a result of climate change.

The Gulf Stream is typically 100 kilometres (62 mi) wide and 800 metres (2,600 ft) to 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) deep. The current velocity is fastest near the surface, with the maximum speed typically about 2.5 metres per second (5.6 mph).

History

European discovery of the Gulf Stream dates to the 1512 expedition of Juan Ponce de León, after which it became widely used by Spanish ships sailing from the Caribbean to Spain.[1] A summary of Ponce de León's voyage log, on April 22, 1513, noted, "A current such that, although they had great wind, they could not proceed forward, but backward and it seems that they were proceeding well; at the end it was known that the current was more powerful than the wind."[2] Its existence was also known to Peter Martyr d'Anghiera.

Benjamin Franklin became interested in the North Atlantic Ocean circulation patterns. In 1768, while in England, Franklin heard a curious complaint from the Colonial Board of Customs: Why did it take British packets several weeks longer to reach New York from England than it took an average American merchant ship to reach Newport, Rhode Island, despite the merchant ships leaving from London and having to sail down the River Thames and then the length of the English Channel before they sailed across the Atlantic, while the packets left from Falmouth in Cornwall?[3]

Franklin asked Timothy Folger, his cousin twice removed (Nantucket Historical Society), a Nantucket island whaling captain, for an answer. Folger explained that merchant ships routinely crossed the then-unnamed Gulf Stream—identifying it by whale behavior, measurement of the water's temperature and the speed of bubbles on its surface, and changes in the water's color—while the mail packet captains ran against it.[3] Franklin worked with Folger and other experienced ship captains, learning enough to chart the Gulf Stream and giving it the name by which it is still known today. He offered this information to Anthony Todd, secretary of the British Post Office, but it was ignored by British sea captains.[3]

Franklin's Gulf Stream chart was published in 1770 in England, where it was mostly ignored.[4] Subsequent versions were printed in France in 1778 and the U.S. in 1786.[5]

Properties

The Gulf Stream proper is a western-intensified current, driven largely by wind stress.[6] The North Atlantic Drift, in contrast, is largely thermohaline circulation–driven. In 1958 the oceanographer Henry Stommel noted that "very little water from the Gulf of Mexico is actually in the Stream".[7] By carrying warm water northeast across the Atlantic, it makes Western and especially Northern Europe warmer than it otherwise would be.[8]

However, the extent of its contribution to the actual temperature differential between North America and Europe is a matter of dispute, as there is a recent minority opinion within the science community that this temperature difference (beyond that caused by contrasting maritime and continental climates) is mainly due to atmospheric waves created by the Rocky Mountains.[9]

Formation and behaviour

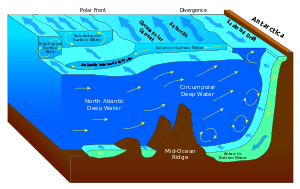

A river of sea water, called the Atlantic North Equatorial Current, flows westward off the coast of Central Africa. When this current interacts with the northeastern coast of South America, the current forks into two branches. One passes into the Caribbean Sea, while a second, the Antilles Current, flows north and east of the West Indies.[10] These two branches rejoin north of the Straits of Florida.

The trade winds blow westward in the tropics,[11] and the westerlies blow eastward at mid-latitudes.[12] This wind pattern applies a stress to the subtropical ocean surface with negative curl across the north Atlantic Ocean.[13] The resulting Sverdrup transport is equatorward.[14]

Because of conservation of potential vorticity caused by the northward-moving winds on the subtropical ridge's western periphery and the increased relative vorticity of northward moving water, transport is balanced by a narrow, accelerating poleward current, which flows along the western boundary of the ocean basin, outweighing the effects of friction with the western boundary current known as the Labrador current.[15] The conservation of potential vorticity also causes bends along the Gulf Stream, which occasionally break off due to a shift in the Gulf Stream's position, forming separate warm and cold eddies.[16] This overall process, known as western intensification, causes currents on the western boundary of an ocean basin, such as the Gulf Stream, to be stronger than those on the eastern boundary.[17]

As a consequence, the resulting Gulf Stream is a strong ocean current. It transports water at a rate of 30 million cubic meters per second (30 sverdrups) through the Florida Straits. As it passes south of Newfoundland, this rate increases to 150 million cubic metres per second.[18] The volume of the Gulf Stream dwarfs all rivers that empty into the Atlantic combined, which barely total 0.6 million cubic metres per second. It is weaker, however, than the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.[19]

The Gulf Stream is typically 100 kilometres (62 mi) wide and 800 metres (2,600 ft) to 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) deep. The current velocity is fastest near the surface, with the maximum speed typically about 2.5 metres per second (5.6 mph).[20] As it travels north, the warm water transported by the Gulf Stream undergoes evaporative cooling. The cooling is wind-driven: Wind moving over the water causes evaporation, cooling the water and increasing its salinity and density. When sea ice forms, salts are left out of the ice, a process known as brine exclusion.[21] These two processes produce water that is denser and colder (or, more precisely, water that is still liquid at a lower temperature). In the North Atlantic Ocean, the water becomes so dense that it begins to sink down through less salty and less dense water. (The convective action is not unlike that of a lava lamp.) This downdraft of cold, dense water becomes a part of the North Atlantic Deep Water, a southgoing stream.[22] Very little seaweed lies within the current, although seaweed lies in clusters to its east.[23]

Localised effects

The Gulf Stream is influential on the climate of the Florida peninsula. The portion off the Florida coast, referred to as the Florida current, maintains an average water temperature at or above 24 °C (75 °F) during the winter.[24] East winds moving over this warm water move warm air from over the Gulf Stream inland,[25] helping to keep temperatures milder across the state than elsewhere across the Southeast during the winter. Also, the Gulf Stream's proximity to Nantucket, Massachusetts adds to its biodiversity, as it is the northern limit for southern varieties of plant life, and the southern limit for northern plant species, Nantucket being warmer during winter than the mainland.[26]

The North Atlantic Current of the Gulf Stream, along with similar warm air currents, helps keep Ireland and the western coast of Great Britain a couple of degrees warmer than the east.[27] However, the difference is most dramatic in the western coastal islands of Scotland.[28] A noticeable effect of the Gulf Stream and the strong westerly winds (driven by the warm water of the Gulf Stream) on Europe occurs along the Norwegian coast.[8] Northern parts of Norway lie close to the Arctic zone, most of which is covered with ice and snow in winter. However, almost all of Norway's coast remains free of ice and snow throughout the year.[29] Weather systems warmed by the Gulf Stream drift into Northern Europe, also warming the climate behind the Scandinavian mountains.

Effect on cyclone formation

The warm water and temperature contrast along the edge of the Gulf Stream often increase the intensity of cyclones, tropical or otherwise. Tropical cyclone generation normally requires water temperatures in excess of 26.5 °C (79.7 °F).[30] Tropical cyclone formation is common over the Gulf Stream, especially in the month of July. Storms travel westward through the Caribbean and then either move in a northward direction and curve toward the eastern coast of the United States or stay on a north-westward track and enter the Gulf of Mexico.[31] Such storms have the potential to create strong winds and extensive damage to the United States' Southeast Coastal Areas.

Strong extratropical cyclones have been shown to deepen significantly along a shallow frontal zone, forced by the Gulf Stream itself during the cold season.[32] Subtropical cyclones also tend to generate near the Gulf Stream. 75 percent of such systems documented between 1951 and 2000 formed near this warm water current, with two annual peaks of activity occurring during the months of May and October.[33] Cyclones within the ocean form under the Gulf Stream, extending as deep as 3,500 metres (11,500 ft) beneath the ocean's surface.[34]

Possible renewable power source

The theoretical maximum energy dissipation from Gulf Stream by turbines is in the range of 20-60 GW.[35] One idea, which would supply the equivalent power of several nuclear power plants, would deploy a field of underwater turbines placed 300 meters (980 ft) under the center of the core of the Gulf Stream.[36] Ocean thermal energy could also be harnessed to produce electricity utilizing the temperature difference between cold deep water and warm surface water.[37]

In culture

- Some of the RMS Titanic's victims, whose bodies were buoyed by lifebelts but were never found by rescue or recovery ships sent to find them, are surmised to have been carried away in the Gulf Stream.[38][39][40]

See also

- Arctic dipole anomaly

- Boundary current

- Humboldt Current

- Latitude of the Gulf Stream and the Gulf Stream north wall index

- North Atlantic oscillation

- Shutdown of thermohaline circulation

References

- ↑ Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 194. ISBN 0-393-06259-7.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Jerry. "History of the Gulf Stream". Keys Historeum. Historical Preservation Society of the Upper Keys. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 Tuchman, Barbara W. The First Salute: A View of the American Revolution New York: Ballantine Books, 1988. pp.221–222.

- ↑ Isserman, Maurice (2002). "Ben Franklin and the Gulf Stream" (PDF). Study of place. TERC. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ↑ Anon. "1785: Benjamin Franklin's 'Sundry Maritime Observations'". Ocean Explorer: Readings for ocean explorers. NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ↑ Wunsch, Carl (November 8, 2002). "What Is the Thermohaline Circulation?". Science. 298 (5596): 1179–1181. doi:10.1126/science.1079329. PMID 12424356. (see also Rahmstorf.)

- ↑ Henry Stommel. (1958). The Gulf Stream: A Physical and Dynamical Description. Berkeley: University of California Press. p.22

- 1 2 Barbie Bischof; Arthur J. Mariano; Edward H. Ryan (2003). "The North Atlantic Drift Current". The National Oceanographic Partnership Program. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Seager, Richard (July–August 2006). "The Source of Europe's Mild Climate". American Scientist Online. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ↑ Elizabeth Rowe; Arthur J. Mariano; Edward H. Ryan. "The Antilles Current". Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "trade winds". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Westerlies. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-04-15.

- ↑ Matthias Tomczak and J. Stuart Godfrey (2001). Regional Oceanography: an Introduction. Matthias Tomczak, pp. 42. ISBN 81-7035-306-8. Retrieved on 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Earthguide (2007). Lesson 6: Unraveling the Gulf Stream Puzzle - On a Warm Current Running North. University of California at San Diego. Retrieved on 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Angela Colling (2001). Ocean Circulation. Butterworth-Heinemann, p. 96. Retrieved on 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Maurice L. Schwartz (2005). Encyclopedia of Coastal Science. Springer, p. 1037. ISBN 978-1-4020-1903-6. Retrieved on 2009-05-07.

- ↑ National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (2009). Investigating the Gulf Stream. North Carolina State University. Retrieved on 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Joanna Gyory; Arthur J. Mariano; Edward H. Ryan. "The Gulf Stream". Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Ryan Smith; Melicie Desflots; Sean White; Arthur J. Mariano; Edward H. Ryan. "The Antarctic CP Current". Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Phillips, Pamela. "The Gulf Stream". USNA/Johns Hopkins. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ Russel, Randy. "Thermohaline Ocean Circulation". University Corportation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Behl, R. "Atlantic Ocean water masses". California State University Long Beach. Archived from the original on May 23, 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Edward and George William Blunt (1857). The American Coast Pilot. Edward and George William Blunt. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Geoff Samuels (2008). "Caribbean Mean SSTs and Winds". Cooperative Institute For Marine and Atmospheric Studies. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center. Climatic Wind Data for the United States. Retrieved on 2007-06-02. Archived June 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sarah Oktay. "Description of Nantucket Island". University of Massachusetts Boston. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ Professor Hennessy (1858). Report of the Annual Meeting: On the Influence of the Gulf-stream on the Climate of Ireland. Richard Taylor and William Francis. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ↑ "Satellites Record Weakening North Atlantic Current Impact". NASA. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Erik A. Rasmussen; John Turner (2003). Polar Lows. Cambridge University Press. p. 68.

- ↑ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: How do tropical cyclones form?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-26.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ S. Businger, T. M. Graziano, M. L. Kaplan, and R. A. Rozumalski. Cold-air cyclogenesis along the Gulf-Stream front: investigation of diabatic impacts on cyclone development, frontal structure, and track. Retrieved on 2008-09-21.

- ↑ David M. Roth. P 1.43 A FIFTY YEAR HISTORY OF SUBTROPICAL CYCLONES. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2008-09-21.

- ↑ D. K. Savidge and J. M. Bane. Cyclogenesis in the deep ocean beneath the Gulf Stream. 1. Description. Retrieved on 2008-09-21.

- ↑ Ocean Current Energy Assessment for the Gulf Stream Xiufeng Yang*, Kevin A. Haas, Hermann M. Fritz Retrieved 2014-05-26

- ↑ The Institute for Environmental Research & Eductation. Tidal.pdf Retrieved on 2010-07-28.

- ↑ Jeremy Elton Jacquot. Gulf Stream's Tidal Energy Could Provide Up to a Third of Florida's Power. Retrieved on 2008-09-21.

- ↑ "Recovering the Dead". titanic-titanic.com.

- ↑ Walter Lord. The Night Lives On.

- ↑ Ticehurst, Brian J. (March 31, 2007). "CLASSified in Death : Recovering the Titanic's dead". Encyclopedia Titanica.

Further reading

- Corona Magazine Issue 124: Science (German, Transported amount of power)

- Hátún; Sandø, AB; Drange, H; Hansen, B; Valdimarsson, H; et al. (September 16, 2005). "Influence of the Atlantic Subpolar Gyre on the Thermohaline Circulation". Science. 309 (5742): 1841–1844. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.1841H. doi:10.1126/science.1114777. PMID 16166513. Archived from the original on 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2007-08-02. (Increased temperature and salinity in the Nordic Seas.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gulf stream. |

- Ocean Motion—Description of the Gulf Stream as a western boundary current