Great desert skink

| Great desert skink | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Sauria |

| Infraorder: | Scincomorpha |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Subfamily: | Lygosominae |

| Genus: | Liopholis |

| Species: | L. kintorei |

| Binomial name | |

| Liopholis kintorei (Stirling & Zietz, 1893) | |

| Synonyms | |

The great desert skink (Liopholis kintorei ) is a species of skink in the genus Liopholis native to the western half of Australia.[3] They are burrowing lizards and extremely social.

Etymology

The specific name, kintorei, is in honor of Algernon Keith-Falconer, 9th Earl of Kintore, a British politician who was a colonial governor of South Australia.[4]

Description

Great desert skinks are medium-sized skinks, reaching an average snout-to-vent length (SVL) of 19 cm (approx. 7 in). They have smooth, small, glossy scales and are mostly rust-colored on the top of their body, with their belly a vanilla color. They have relatively large circular eyes and a short snout.

Distribution and habitat

These Australian skinks are native to the southwestern quarter of the Northern Territory, and dispersed slightly throughout most of Western Australia. As the common name suggests, they are desert reptiles, living in burrows. The burrows can extend up to 12 meters (40 ft) in length, and can have as many as 20 entrances.[5]

Behaviour

Researchers have recently made a stunning discovery with these skinks — out of over 5,000 species of lizard documented, this species has been said to have "unique" behavior among them.[5] They appear to work in cooperation with one another to build and take care of their burrows, even digging out specific rooms for use as a defecatorium. Mates are faithful to one another and always mate with the same lizard, although 40 percent of males have been documented to mate with other females. The tunnels are mostly excavated by adults, while juvenile lizards contribute small "pop" holes to the system. DNA analysis has shown that immature lizards live in the same burrow with their siblings, regardless of age difference. The study, carried out in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, also revealed that all immature lizards were full siblings in 18 of 24 burrow systems. Researchers have confirmed that the lizards are family-based and keep the juveniles in the tunnel system until they mature.

References

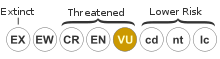

- ↑ Australasian Reptile & Amphibian Specialist Group (1996). "Liopholis kintorei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Liopholis kintorei ". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- ↑ Great desert skink at the Australian Reptile Online Database

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. 2011. The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Egernia kintorei, p. 141).

- 1 2 "Cooperative Lizard Living." Reptile Channel. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

Further reading

- Stirling EC, Zietz A. 1893. Scientific Results of the Elder Exploring Expedition. Vertebrata. Mammalia. Reptilia. Trans. Royal Soc. South Australia 16: 154-176. (Egernia kintorei, new species, p. 171).