Glavatičevo

| Glavatičevo | |

|---|---|

| Village | |

| Nickname(s): Župa, Komska Župa | |

| Motto: "Nera-Etwa" - Celtic for "Divinity that flows" referring to the Neretva river ; Bosnian: "Neretva je Božanstvo koje teče" | |

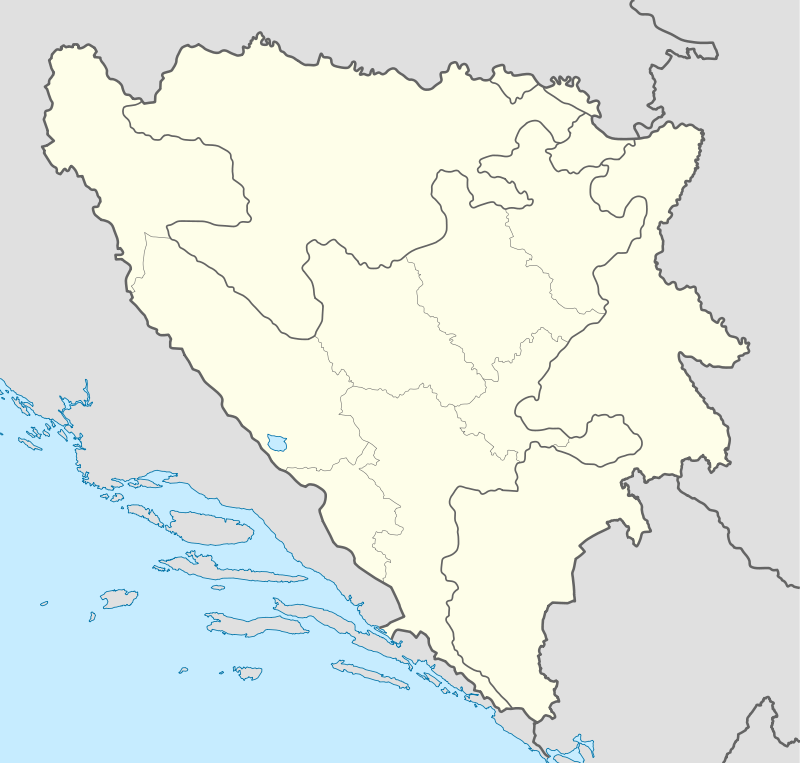

Konjic Municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which Glavatičevo belongs to. | |

Glavatičevo Location of Glavatičevo within Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Coordinates: 43°30′12.91″N 18°6′17.25″E / 43.5035861°N 18.1047917°ECoordinates: 43°30′12.91″N 18°6′17.25″E / 43.5035861°N 18.1047917°E | |

| Country |

|

| Entitet | Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Canton | Herzegovina-Neretva Canton |

| Village founded | Between 1330-1400 |

| Named for | One theory say that Glavatičevo is named after the medieval nobleman Glavat or Glavatec, who was out of the area, another say that Glavatičevo is named after the endemic fish Salmo marmoratus from Neretva calld Glavatica. |

| Government | |

| • Type | Local Community |

| Area | |

| • Village | 225 km2 (87 sq mi) |

| • Land | 175 km2 (68 sq mi) |

| • Water | 8 km2 (3 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 50 km2 (20 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3 km2 (1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 365 m (1,198 ft) |

| Population (1991 census) | |

| • Village | 1,945 |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

| Area code(s) | +387 36 |

| Website |

www |

Glavatičevo is a small village in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The village lies 30km southeast of Konjic, within the wide Župa valley (also Komska Župa and Konjička Župa) (English: Parish = Bosnian: Župa) straddling the Neretva river, in Konjic Municipality, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Geography and climate

One theory say that Glavatičevo is named after the medieval nobleman Glavat or Glavatec, who was out of the area, another say that Glavatičevo is named after the endemic fish Salmo marmoratus from Neretva called Glavatica. Dr. Pavao Anđelić in his book "Spomenici Konjica i okoline" claimed that Glavatičevo derived its name from that of the local nobleman Glavat or Glavatec.

Villages

Villages in the Župa valley include Biskup, Dudle, Dužani, Grušča, Janjina, Kašići, Krupac, Kula-Čičevo, Lađanica, Razići, Ribari. The wider area of Župa includes the villages of Bijelimići, Dindol, Bukovica,...

Natural heritage

Glavatičevo and Župa valley belongs to Upper Neretva (Bosnian: Gornja Neretva), which is upper course of the Neretva river, and includes vast area around the Neretva, numerous streams and well-springs, three major glacial lakes near the very river and even more scattered across the mountains of Treskavica and Zelengora in wider area of the Upper Neretva, mountains, peaks and forests, flora and fauna of the area. All this natural heritage together with cultural heritage of Upper Neretva, representing rich and valuable resources of Glavatičevo, whole Župa valley as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Neretva river

The Neretva is largest karst river in the Dinaric Alps in the entire eastern part of the Adriatic basin, which belongs to the Adriatic river watershed. The total length is 230 km, of which 208 km are in Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the final 22 km are in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County of Croatia.[1][2]

Geographically and hydrologically the Neretva is divided in three section.[2] Its source and headwaters gorge are situated deep in the Dinaric Alps at the base of the Zelengora and Lebršnik mountains, under the Gredelj saddle. The source is at 1,227 m.a.s.l. First section of the Neretva course from source all the way to the town of Konjic, the Upper Neretva, flow from south to north - north-west as most of the Bosnia and Herzegovina rivers belonging to the Danube watershed, and cover some 1,390 km2 with average elevation of 1.2%. The upper course of Neretva, Upper Neretva (Bosnian: Gornja Neretva) has water of Class I purity[3] and is almost certainly the coldest river water in the world, often as low as 7-8 degrees Celsius in the summer months. Rising from the base of the Zelengora and Lebršnik mountain, Neretva headwaters run in undisturbed rapids and waterfalls, carving steep gorges reaching 600–800 meters in depth through this remote and rugged limestone terrain.

Right below Konjic, the Neretva briefly expanding into a wide valley which provides fertile agricultural land. There exists a large Jablaničko Lake, artificially formed after construction of dam near Jablanica.

Streams and Neretva tributaries

Rivers of the Ljuta, the Jesenica, the Bjelimićka Rijeka, the Slatinica, the Račica, the Rakitnica flow into the Neretva from the right, while the Živašnica (also Živanjski Potok), the Ladjanica, the Župski Krupac, the Bukovica, the Šištica flow into it from the left.

Rakitnica river

Rakitnica is the main tributary of the first section of the Neretva river known as Upper Neretva (Bosnian: Gornja Neretva). The Rakitnica river formed a 26 km long canyon, of its 32 km length, that stretches between Bjelašnica and Visočica to southeast from Sarajevo.[4] From the canyon, there is a hiking trail along the ridge of the Rakitnica canyon, which drops 800 m below, all the way to famous village of Lukomir. Village is the only remaining traditional semi-nomadic, Bosniak, mountain village in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At almost 1,500 m, the village of Lukomir, with its unique stone homes with cherry-wood roof tiles, is the highest and most isolated mountain village in the country. Indeed, access to the village is impossible from the first snows in December until late April and sometimes even later, except by skis or on foot. A newly constructed lodge is now complete to receive guests and hikers.

Lakes

Boračko lake

Endemic and endangered species

Trout

The river Neretva and its tributaries represent the main drainage system in the east Adriatic watershed and the foremost ichthyofaunal habitat of the region. Salmonidae fishes from the Neretva basin show considerable variation in morphology, ecology and behaviour. Neretva also has many other endemic and fragile life forms that are near extinction. Among most endangered are three endemic species of Neretva trout: Neretvanska Mekousna (Salmo obtusirostris oxyrhynchus),[5] Zubatak (Salmo dentex)[6] and Glavatica (Salmo marmoratus).[7]

All three endemic trout species of Neretva are endangered mostly due to destruction of the habitat and hybridisation with introduced trout and illegal fishing as well as poor management of water and fisheries (dams, overfishing, mismanagement).[8][9]

Ecology and protection

Dam problems

The benefits brought by dams have often come at a great environmental and social cost,[10][11][12] as dams destroy ecosystems[13] and cause people to lose their homes and livelihoods.

The Neretva and two main tributaries are already harnessed, by four HE power-plants with large dams on Neretva, one HE power-plants with major dam on the Neretva tributary Rama, and two HE power-plants with one major dam on the Trebišnjica river, which is considered as part of the Neretva watershed.

Also, the government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity has unveiled plans to build three more hydroelectric power plants with major dams (as over 150.5 meters in height)[14] upstream from the existing plants, beginning with Glavaticevo Hydro Power Plant in the nearby Glavatičevo village, then going even more upstream Bjelimići Hydro Power Plant and Ljubuča Hydro Power Plant located near the villages with a same names; and in addition one more at the Neretva headwaters gorge, near the very source of the river in entity of Republic of Srpska by its entity government. This, if realized, would completely destroyed this jewel among rivers, so its strongly opposed and protested by numerous environmentalist organizations and NGO's, domestic[15] as well as international,[16][17][18] who wish for the canyon, considered at least beautiful as the Tara canyon in Bosnia and Herzegovina and nearby Montenegro, to remain untouched and unspoiled, hopefully protected too.[19][20]

Moreover, the same Government Of FBiH preparing a parallel plan to form a huge National Park which include entire region of Gornja Neretva (English: Upper Neretva), and within Park those three hydroelectric power plants, which is unheard in the history of environmental protection. The latest idea is that the park should be divided in two, where the Neretva should be excluded from both and, in fact, become the boundary between parks.

This is a cunning plan of engineers and related ministry in Government Of FBiH and should leave the river available for the construction of three large dams, and give them hope in order to remove the fear of contradiction in the plans for environmental protection in the area and the flooding its very heart, in terms of natural values - the Neretva. Of course, such deception failed, because the concerned citizens from the local community are not given bluff, as well as concerned citizens of whole country, and its particularly strongly opposed by NGOs and other institutions and organizations that are interested in establishing the National Park of Upper Neretva towards the professional and scientific principles and not according to the needs of electric energy lobby.[21][22]

Vajont Dam disaster

Cultural heritage

Stećci

The Stećci (singular: Stećak) are monumental medieval tombstones that lie scattered across the landscape of Bosnia and Herzegovina. They are the country's most legendary symbol.[23][24] Although many of them are found in Serbia and Croatia, the vast majority are found within the borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina – 60,000 in all, of which approximately 10,000 are decorated (and sometimes inscribed). Appearing in the 12th century, the stećci reached their peak in the late 14th to 15th centuries, before dying away during the Ottoman occupation. Their most remarkable feature is their decorative motifs, many of which remain enigmatic to this day. Although its origins are within the Bosnian Church, all evidence points to the fact that stećci were erected in due time by adherents of the Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholic Bosnians alike.

District Komska Župa or Glavatičevo, is full stećci. Some of them, and there are hundreds, are a true rarity. In the necropolis Sanković, at the Grčka glavica (English: Greece peak), in the area of Biskup village (English: Bishop), there are about 115 stećak tombstones. The most famous is the stećak on the grave of Goisava Sanković, from aristocratic Sanković family. Among these decorated stećak, two are decorated with motifs of vines. In Kasići there is a group of five stećak tombstones. One is decorated, and one has a label that was partially damaged, but can nevertheless be translated. In Krupac, in one of two lone stećak, there is a drawing of Crescent. Near Razići, at Crkvine hamlet, there is a huge necropolis of 93 stećak, decorated with the only three interesting themes. In one drawing is the human head, "that makes the spirits go away" and it is likely that below this carving, probably, a Bogumil was buried. On the second is a carved cross which signified that under this stećak is Christian, while the third stećak has a crescent moon under which, probably, rests a local inhabitant who accepted Islam. The hamlet Račica at the place which is called Gromile, there are two lone stećak. One of them has two podiums, which is very rarely. On the Visočica mountain, on the Poljica, in a really great necropolis tombstones are two stećak: Vukosav Lupčić and Rabrena Vukić with inscriptions

Ancient road

Roman road from Narona (Village Vid at Metković) ran over Nevesinjsko field and Dubrava, and on the location of Velika Poljana, near Lipeta, join with main rout. Solid construction of the Roman roads, making it clearly visible even today, from Lipeta to Vrabča. Milestones found in Konjic at the mouth of the Bijela river, in Polje, Borci village, Kuli, Malom Polju near Lipeta, all mentioning Roman emperors Augustus, Dacija, Tacitus, and Philip Augustus. That means that the Romans constructed these roads sometime in the 1st century and with significant reconstructed during the 3rd century, and continuously used in the Middle Ages as the closest connection from Dubrovnik Republic with trading centers in Bosnia. From Lipeta to Konjic, Roman Road and the Turkish route have been built almost on the same route. During Ottoman rule, there was a vital traffic between Sarajevo and Mostar. How important this road was in the Middle Ages Bosnia, tells us his name: "Džada Mostar", "Great road of Mostar" or "Sarajevo road". Even the Romans had forts to ensure traffic and the protection of passengers on this rout. During the Middle Ages, except fortifications, along the way were built settlements. In Ottoman times along the way were made Karaula (English: Watchtower), with a mission to protect the passengers. Karaula are placed on peaks, canyons and places that are ideal for the attacker and the most dangerous for passengers. Along the road shelters were built for the night sleep and rest of passing travelers. On the Roman road these shelters were called diversarium. With diversarium was a shop, stable, shelter or barn, blacksmith's shop for repair of wagons and shoeing. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Roman road were neglected. At the time of the Bosnian kings, all the imports and exports of goods going towards Dubrovnik Republic and back. People traveled with caravans and lodged under the starry sky, there were fewer shalters at the time like in Konjic and Vrabč. After the occupation of Bosnia by the Ottoman empire, a new shelters called hans were built. Hans served for lodging and accommodation of travelers called "kiridžija" and their caravans, but also the trade took place in these hans as well. During the Ottoman rule hans were a form of "bed and breakfast" facilities, to meet basic needs, these were buildings with dining room, rooms for passengers, room for hadžije (English: Hajjis), shops, stables for horses.[25]

History

Early history

There are a lot of reliable signs and evidences of human life in ancient period of this region. The oldest written record is actually a tombstone from the 2nd century AD raised by Elije Pinnes and Temus, parents of Pinniusu the Roman soldier of the 2.Legion Auxiliary. At the nearby Dernek were found many parts of ceramics from the Roman era. From the Early Stone Age there is no evidence of living in Glavatičevo, although there are signs of ancient inhabitants in wider area. Pieces of ceramics from the Late Stone Age period were found in the sites of Gradac, Lonac and Vijenac near Razići, and sites of Šibenik and Kom near Kašići.

Middle age

Numerous sources confirm that Glavatičevo area and the wider surrounding countryside, from the 12th century until the arrival of the Ottoman empire, was very important for medieval Bosnian Kingdom, apart from the military significant, also, both economically and culturally. Komska Župa (English: Parish = Bosnian: Župa), or area of the current Glavatičevo at that time was a very important road junction. For securing crossing over the Neretva river, near Glavatičevo has built town of Gradac with the citadel. Center of the developed area was the old town of Kom, whose ruins are now preserved on the hard viable top mountain ridge above the village Kašići. The whole Župa area was named after the ancient town of Kom, Komska Župa. Kom was a significant military, economic and cultural center of ancient medieval Bosnian Kingdom and aristocratic Sanković family. The first written document on Kom originate from the 12th century, as a part of the famous "Ljetopis popa Dukljanina" by pop Dukljanin (English: "Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja"). A lot of trading have been happening in Komska Župa at the time. Dubrovnik Republic (also Republic of Ragusa) had a leading role in this. 15 May 1391 Vojvoda (English: Duke=Bosnian: Vojvoda) Radić Sanković issued Charter to Dubrovnik merchants that can trade on its territory, including Komsku Župu. As proof of this trading is discovery of coins from Dubrovnik Republic, as well as a document from 1381 which mentions the clearance of goods in this region. Thus, in Kom worked custom office. At the end of 14th century Kom are still mentioned as a Župa (English: Parish = Bosnian: Župa). It was rare, because the other noble estates were already called principality. Therefore, the area Kom was continued to be called a Župa and that the name has been preserved to these days. Aristocratic Kosača family governed Komska Župa until the second half of 1465. But two years earlier, 1463, after the war campaign, Turkish Sultan Mehmed II el Fatih conquered the area of Konjic and Kom, but that same year Herceg Stjepan Vukčić Kosača and his sons went to counterattack and restored Kom and its surrounding area. Two years is a peace reigned again, but in constant fear of a new Turkish attack. In mid-1465 The Turkish army under the command of Isa-Beg Isaković invaded the land of Herceg Stjepan and won. That was final fall of Kom. Komska Župa became nahia and has been Kadiluku Blagaj. It can be seen from the list of Bosnian Sandžak from 1469 (During the Ottoman times Bosnia was both a single sanjak, and after 1580 a pashaluk divided into several sanjaks).

World War II

German troops invaded Yugoslavia on 17 April 1941 and invaded Konjic at the same time. The village of Glavatičevo was established under Ustaše control. Police station commander Philip Didić and Fra Andelko Nuić Didić made mass arrests, persecution and killings of Bosniaks and Serbs in Glavatičevo and the surrounding area. Honest people were vanished overnight.

On 8 September 1941, at the Boračko Lake, Konjic partisan detachment was founded by communists from Mostar and Konjic: Salko Fejica, Alija Delić, Nijaz Saric, Osman Grebo - Osa, Šaćir Palata, Hasan Bubić, Džemal Dragnić, Aziz Kuluder, Nono Belša, Muhamed Pirkić and Uglješa Danilović, who was also a member of the Party Provincial Committee. The first armed conflict took place on the Boračko Lake on 15 September 1941, when 25 Ustaša soldiers came from the direction of town of Konjic, led by commander of the local death camp Zvonko Jerković. Partisans of the Konjic Battalion surrounded and captured enemy. On that occasion the first victim fell on the side of the partisans - Šaćir Palata. Ustaša were captured and the first People's Court was organized, and judged the evildoers. Battalion was then divided into three companies. The first batch operated on the plateau of Borci village, the second in Glavatičevo area, a third at Blace village area. In April 1942 the battalion had about 450 fighters, which were grouped into six companies.

In early May 1942, begins četniks treason. In Glavatičevo was established četniks command. Since then, until the fourth enemy offensives Glavatičevo was ruled by četniks. Četniks, which was around 3000 commanded by warlord "Duke" Baja Stanišić.

Glavatičevo was liberated 14 February 1945 by parts of the 11th and 14th Hercegovacka Brigade. During the final operations for the liberation, battles were fought near the bridge and Bukovica. After Glavatičevo was liberated, the fighters of this region continue fighting for the liberation of Konjic, Ivan Sedlo mountain and for the final liberation of the former Yugoslavia.

Yugoslavia (1945–92)

After the war Glavatičevo area was divided into two local boards: the local board of Glavatičevo and the local board of Ribari, which is later associated to Glavatičevo. 1952 Glavatičevo becomes municipality and it remains the next 6 years. Immediately after the establishment of the municipality on the river Lađanica has built a small hidro electrical power station on Republic Day 29 November 1952, and the first bulb is finally beginning to radiate in Glavatičevu. A year later the stage of the road Boračko Lake - Glavatičevo was built, with which Glavatičevo is connected with Konjic, Mostar and Sarajevo. Glavatičevo slowly grew and in a few years village got large agricultural cooperatives building, and within that building two shops, caffe-shop, cinema and theatre hall for multiple purpose. In 1958 emerged the first generation of students form elementary school in Glavatičevu, the same year the building of a new school with six classrooms, collections, library and courtyard was completed. Even earlier was finished the primary school in Ribari in 1955, and Grušči in 1956. At that time Glavatičevo had doctors who worked part-time, and paramedic. Period of eighties can be called the golden period for Glavatičevo. In this period many new jobs in various companies were created, so people did not depend just on agriculture and livestock anymore, which until that period was the main source of living and survival. Employees were around 600 and in Unis's factory of aluminum products, Military Post Office, in the ŠIP, Unevit's shops, etc. There was also Zadruga (English: Co-op = Bosnian: Zadruga) with about 30 subcontractors. Apart from these enterprises, Glavatičevo had a large and stabile infrastructure: eight year Primary School "7 Banijska Division", cultural center, mall which was opened in June 1988, water supply, state road, post office, mosques, churches, chapels. Apart from the primary school in Glavatičevo there were two regional schools, one in Grušci and other in Ribari, which was closed in 1985 and merged with the central school in Glavatičevo.

Bosnian War

Demographic

The basis of the list is the source material of the Statistical Institute Bulletin RBiH 119 from January 1991 and Bosnian Congress USA web site as well as Glavatičevo web site[26][27]

1879

| Village name | House No. | Household No. | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biskup | 8 | 8 | 45 |

| Dudle | 7 | 7 | 46 |

| Dužani | 9 | 9 | 59 |

| Glavatičevo | 34 | 58 | 203 |

| Grušča | 25 | 26 | 164 |

| Janjina | 5 | 6 | 32 |

| Kašići | 9 | 11 | 61 |

| Kula-Čičevo | 22 | 22 | 194 |

| Lađanica | 5 | 7 | 39 |

| Razići | 15 | 15 | 91 |

| Ribari | 10 | 10 | 85 |

| Total | 149 | 179 | 1019 |

1991

Village of Glavatičevo - total: 1945 Number of households: 496

- Bosniaks 70%

- Serbs 23%

- Croats 7%

See also

| Water bodies | Settlements | Protected environment and treasures | Nature and culture |

References

- ↑ "Neretva River Sub-basin". INWEB Internationally Shared Surface Water Bodies in the Balkan Region. Retrieved 19 March 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 "Hydrological characteristics of Bosnia and Herzegovina - Adriatic watershed". Hydro-meteorological institute of Federation of B&H. Retrieved 10 March 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Water Quality Protection Project - Environmental Assessment". World Bank. Retrieved 18 June 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ BHTourism - Rakitnica

- ↑ "Salmo obtusirostris". Balkan Trout Restoration Group. Retrieved 10 March 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Salmo dentex". Balkan Trout Restoration Group. Retrieved 10 March 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Salmo marmoratus". Balkan Trout Restoration Group. Retrieved 10 March 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Freyhof, J.; Kottelat, M. (2008). "Salmo dentex". 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 5 August 2007. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Crivelli, A.J. (2006). "Salmo marmoratus". 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 5 August 2007. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Hydroelectric power's dirty secret revealed". New Scientist - Environment. Retrieved 18 June 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Our view of the Hydroelectrical Power Station System "Upper Neretva"" (PDF). ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation Of The Neretva River And Environment Protection. Retrieved 22 June 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Dams–Impact of dams". Science Encyclopedia, vol.2.

- ↑ Environmental Impact of Dams

- ↑ "Methodology and Technical Notes". Watersheds of the World. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

A large dam is defined by the industry as one higher than 15 meters high and a major dam as higher than 150.5 meters.

- ↑ "ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation Of The Neretva River And Environment Protection". Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- ↑ "Water power: the upper Neretva River, Bosnia-Herzegovina". WWF - World Wide Fund. Retrieved 10 March 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Fondacija Heinrich Böll". Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ "REC - The Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe". Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ "Living Neretva". WWF - World Wide Fund. Retrieved 18 March 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Declaration For The Protection Of The Neretva River". ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation Of The Neretva River And Environment Protection. Retrieved 22 June 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Silenced Rivers: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams, by Patrick McCully, Zed Books, London, 1996

- ↑ "Arguments Pro&Contra - Why Are We Contra The Hydroelectrical Power Station System "Upper Neretva"" Check

|url=value (help) (ZIP). ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation Of The Neretva River And Environment Protection (http://zeleni-neretva.ba). Retrieved 22 June 2009. - ↑ http://www.openbook.ba/wenzel/marian_wenzel_bosnia_report.htm

- ↑ http://www.openbook.ba/wenzel/marian_wenzel_guardian.htm

- ↑ dr.Ljubo J. Mihić (1978). Battle for wounded on the Neretva - Cultural-historic monuments and recreational centers. Skupština opštine Jablanica, Skupština opštine Prozor. pp. 11–16.

- ↑ Bosnia and Herzegovina - Cenzus

- ↑ Glavaticevo

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neretva. |

- Glavatičevo

- ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation Of The Neretva River And Environment Protection

- 'Declaration For The Protection Of The Neretva River for download - Declaration Initiator, ZELENI-NERETVA Konjic NGO For Preservation Of The Neretva River And Environment Protection

- WWF Panda - Living Neretva

- Regional Programme for Cultural and Natural Heritage in South East Europe Council of Europe - Directorate of Culture, Cultural and Natural Heritage

- Balkan Trout Restoration Group Site

- Center of expertise on hydropower impacts on fish and fish habitat, Canada

- REC Transboundary Cooperation Through the Management of Shared Natural Resources

- Bosnia and Herzegovina Commission for Preservation of National Monuments

- International Rivers

- Interactive site that demonstrates dams' effects on rivers

- Municipal Website of Konjic (Bosnian)

- Website of Konjic (Bosnian) (English)

- Konjicani

- Neretva.org Open Project

- Rafting Neretva

- Ambasada Neretva Rafting