Franklin's electrostatic machine

Franklin's electrostatic machine is a high voltage static electricity generating device that was used by Benjamin Franklin in the mid-eighteenth century for research on electricity. The mechanism supplied sparks of momentary electricity that were stored in a Leyden jar that was designed to store high voltage charges. The basic apparatus consisted of a cranking wheel, a glass globe that was turned around on an axis, a rubbing pad that touched the spinning globe and a set of metal needles to collect electricity generated by the globe. Experiments from it eventually led to the invention of the lightning rod and new theories about electricity that Franklin wrote a book on.

Background

The concept to make man-made electricity by the use of a mechanical machine was not new in Franklin's time. The technology had already been developed by European scientists in the middle of the seventeenth century. In 1663 Otto von Guericke made an apparatus that generated man-made static electricity which used a sphere of sulfur. Later in 1704 Francis Hauksbee made an advanced technology machine for generating static electricity. By 1740 a version of his electrostatic machine was used throughout Europe as a means to generate a supply of static electricity for research. In 1745 a means was developed to store these static electric charges. This was a type of electrical storage condenser capacitor that was referred to as a Leyden jar.[2][3]

Peter Collinson, a businessman from London who corresponded with American and European scientists, donated to Franklin's Library Company of Philadelphia in 1745 a German "glass tube"[1] and instructions on how to make static electricity with it.[4] Collinson was the library's London agent and provided many gifts, services, and the latest technology information from Europe.[5][6][7] Franklin wrote a letter to Collinson on March 28, 1747, thanking him for the gadget and explained what he was doing with the article.[8] He wrote that the tube and the instructions that came with it motivated him and several of his colleagues to get excited about doing serious electrical experimentation.[9]

In 1746 Franklin began his early electrical experiments with a core team that consisted of Ebenezer Kinnersley, Thomas Hopkinson and Philip Syng.[10][11] In the summer of 1747 they had received a complete Electrical Apparatus system from Thomas Penn.[12] While no records exists to tell what all the parts to this system were, it is surmised by Benjamin Franklin historian J. A. Leo LeMay that it was a combination of an electricity generating machine, a Leyden jar, a glass tube, and a stool that was insulated in some way off the ground from passing electricity.[12][13] Franklin and his associates therefore had a complete electrical apparatus system for producing and storing all the electricity they needed for experimental research.[6]

Objects like amber, sulphur, or glass that are rubbed with certain materials produced electrical effects.[14] Franklin theorized this "electrical fire" was collected from this other material somehow and not produced by the actual friction action itself on the object.[15][16] In order to conduct a serious investigation on this and do long term experimental research he decided to retire early from his printing business. In 1748, Franklin in his early forties turned over his entire operation to his business partner David Hall.[17] He then moved into his new Philadelphia home with his wife and made it a place for laboratory experimenting and research on these new electricity theories.[18][19] Franklin then experimented not only with the electrostatic machine with the glass globe, but with the electric Leyden jar wet cell as well to try to figure out how it worked.[20] He kept a detailed journal of his research in a diary called "Electrical Minutes" that has since been lost.[21]

Description

Franklin used a hand operated wheel and pulley type machine (designed like a hand operated knife sharping grindstone) that could be operated by one person using a handle.[20] The motion rubbed a large glass bulb that produced static electricity that he called "Electrical Fire" and the friction machine as an "electric machine."[6] The basic mechanics was of Philip Syng's design and a practical mechanical improvement on ones made in Europe at the time, in that the glass globe could be spun easier. It had an iron axis shaft spindle that was attached to the globe and went through it. Where it came out at the other end of the globe tube a small handle was attached and it could be turned like an everyday grindstone for sharpening knives. This improvement made the basic globe tube machine that produced electricity unique from other electricity producing machines of the time. The bulb mechanism itself was small enough to be portable and could be boxed up and stored away by a person for later use.[22] The glass globe mechanisms were kept in specially designed flannel lined cardboard box cases for protection from breaking and soiling the surface of the glass.[22][23]

The globe tube was made by Wistarburgh Glass Works of New Jersey.[12] Certain element materials were specified by Franklin to be used in the glass formula for the construction make-up. The glass manufacturer and blower was Caspar Wistar, a close associate with Franklin. This was then a scientific glass designed so as to produce static electricity effectively.[24] These were referred to as "electerizing globes and tubes."[25] Wistarburgh Glass Works also made scientific glass for the Leyden jars Franklin needed in the 1750s for additional complete Electrical Apparatus systems he made for himself and others.[12][25]

The glass globe on an axle that rotated had a piece of cloth type material, sometimes a buckskin pad, that rubbed the tube when it spun around. This action caused an electrical charge like rubbing a glass tube with wool cloth by hand, but was less tiring.[22] The electricity, in the form of sparks then went to a set of metal needles that was very close to the spinning globe, passing through a beaded iron chain acting like a copper wire that led to a Leyden jar that received the electricity.[26][27][28][29] Franklin explained that when the great Wheel was used with the basic machine it gave more swiftness on spinning the glass globe.[22] A few simple revolutions, that didn't need to be extremely fast, was all that was needed to charge a Leyden jar.[22][23]

Electrical principles

An electrical principle that Franklin proved in 1747 with his electrostatic machine was that of conservation of charge.[15][22] He was the first to use the terms "positive" and "negative" ("plus" and "minus") as applied to electricity. Franklin expounded on it and wrote detailed letters and documents on his findings from experimenting with the electrostatic machine and Leyden jars.[15][30][31] He concluded that lightning was just giant sparks of these electric charges redistributing themselves.[32] He referred to this static electricity as "electric fire" and sometimes as "electric fluid" and at other times as "electric matter."[33] Franklin had made a list in 1749 of several ways in which lightning had similar characteristics as this electricity.[32] That developed a theory for the "electical fire" as a type of motion travel or current flow rather than a type of explosion.[34] There were new electric terms then developed from his name in the middle of the eighteenth century. For example, "Franklin current" is electrostatic electricity.[35] "Franklinization" is electrotherapy where Franklin applied strong static charges from powerful Leyden jars, which were charged from his electrostatic machine, to treat patients with various illnesses.[36][37]

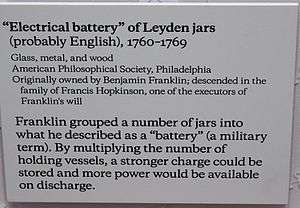

Franklin's experiments in charging a Leyden jar with his electrostatic machine developed into connecting a bank of Leyden jars in series, with "one hanging on the tail of the other", that could all be charged with his electrostatic electricity generating machine.[33] Franklin called these an "Electrical Battery" and used them together for an amplified power effect.[1] The word "battery" was then a military term used at the time for a group of cannons.[38] In compliance with his will, Franklin's Leyden "battery" of jars and the original Collinson 1747 "glass tube" gift to Franklin was given to the Royal Society on April 1, 1836, by Thomas Hopkinson's grandson Joseph Hopkinson.[39]

Franklin and his team of associates observed in using the electrostatic machine that pointed objects had a better effect of "drawing off" and "throwing off" electricity than a blunt object.[40][11] This discovery was first reported by Hopkinson.[18] Franklin thought on how this could be used to a practical advantage in everyday usage.[41] He concluded that perhaps something could be made to attract this electricity out of storm clouds, but first had to verify that these thunder bolts were the same thing as sparks of electricity he had already observed.[41] He wrote Collinson and Cadwallader Colden letters about this theory.[42]

Franklin developed and produced his lightning rod invention from what he learned from his electrostatic machine about static electricity principles as related to pointed objects.[10][43] He proposed an experiment to be done during an electrical storm where a person was to stand inside a sentry box upon a stool containing feet that would not conduct electricity. He was to hold out a long pointed iron rod to attract a lightning bolt.[14] On May 10, 1752, this was first performed with success in France and repeated later several more times throughout Europe. Franklin proved by this sentry-box experiment that lightning was electricity.[14] He determined from this experiment that by placing a pointed iron rod at the top of the roof of a wooden structure and the other end of the rod placed deep into the ground it would protect it. The point would attract the electrical discharge from the cloud and hit the iron rod instead of the structure and go directly into the earth to discharge the electricity, bypassing the structure.[44]

Legacy

"electrostatic machines"

Franklin's distribution to other close associates of his versions of the electrostatic machine caused many to seriously study electricity.[12] By the end of the eighteenth century most scientific laboratories contained a hand operated machine that had some form of an electrostatic machine. Italian anatomist Luigi Galvani had a version of the static electricity producer in his laboratory, which ultimately led to the development of the modern day electric battery.[45]

The chemist Joseph Priestly was mentored and encouraged by Franklin to study electricity with the use of an electrostatic machine with a similar design that Franklin used. Priestly resigned and used his own versions of Franklin's machine for research.[46] In 1767 he published a 700-page book on his findings called The History and Present State of Electricity.[47][48]

Franklin sent many letters to his friend Collinson in London between 1747 and 1750 about his electrical experiments using the electrostatic machine and the Leyden jar.[11] In them he included his observations through experimentation and theories on the principles of how electricity worked. These letters were eventually assembled and initially published in 1751 in a book entitled Experiments and Observations on Electricity. It had four major editions and was translated into several European languages.[49][50][51][52]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 Talbott 2009, p. 185.

- ↑ Grimnes 2014, p. 495.

- ↑ "Benjamin Franklin tries to electrocute a turkey". Massachusetts Historical Society. 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ↑ Cohen 1990, p. 61.

- ↑ Lemay 2009, pp. 58–59.

- 1 2 3 Crane 1954, p. 48.

- ↑ Pasles 2008, p. 119.

- ↑ Lemay 2009, p. 67.

- ↑ "From Benjamin Franklin to Peter Collinson, 28 March 1747". Founders Online. National Historical Publications and Records Commission. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- 1 2 Maclean 1877, p. 142.

- 1 2 3 Talbott 2009, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lemay 2009, p. 75.

- ↑ Garche 2013, p. 596.

- 1 2 3 Cohen 1990, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Talbott 2009, p. 184.

- ↑ Lemay 2009, p. 71.

- ↑ Waldstreicher 2005, pp. 126–127.

- 1 2 Finger 2012, p. 85.

- ↑ "Franklin's Lightning Rod". The Franklin Institute. 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- 1 2 Tucker 2009, p. 40.

- ↑ Lemay 2009, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lemay 2009, p. 72.

- 1 2 Cohen 1956, p. 440.

- ↑ "The Wistars and their Glass 1739 – 1777". WheatonArts. 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- 1 2 Bridenbaugh 2012, p. 63.

- ↑ McNichol 2011, pp. 10–16.

- ↑ "Science Encyclopedia". Electrostatic Devices (page 2393). Net Industries. 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ↑ Gregory 1822, p. 8.

- ↑ McGrath 2001, p. 1335.

- ↑ McNichol 2011, p. 16.

- ↑ Malmivuo & Plonsey 1995, p. 13.

- 1 2 Morgan 2003, p. 12.

- 1 2 Cohen 1956, p. 460.

- ↑ Lemay 2009, pp. 72–75.

- ↑ Grimnes 2014, p. 496.

- ↑ Schiffer 2003, pp. 136, 137.

- ↑ "Electro-therapeutics". The Encyclopedia Americana: A universal reference library comprising the arts and sciences. Scientific American Compiling Department. 1905.

- ↑ Lynn 2009, p. 136.

- ↑ Cohen 1956, p. 454B.

- ↑ LeMay 1987, p. 600.

- 1 2 Isaacson 2004, pp. 137–145.

- ↑ Lemay 2009, p. 86–96.

- ↑ Coulson 1950, p. 32.

- ↑ Schafer 1992, p. 58.

- ↑ Avery 2016, p. 207.

- ↑ Pyenson & Gauvin 2002, p. 93.

- ↑ Jackson 2005, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Schofield 1997, pp. 140–150.

- ↑ McNichol 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ "Experiments and observations on electricity". Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Cohen 1956, pp. 432, 478.

- ↑ "From Benjamin Franklin to Peter Collinson, 28 March 1747". Founders Online. National Historical Publications and Records Commission. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

Sources

- Avery, John Scales (14 September 2016). Science and Society. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-3147-73-7.

- Bridenbaugh, Carl (4 May 2012). The Colonial Craftsman. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-14473-3.

- Cohen, I. Bernard (1956). Franklin and Newton: An Inquiry Into Speculative Newtonian Experimental Science and Franklin's Work in Electricity as an Example Thereof. Harvard University Press.

- Cohen, I. Bernard (1990). Benjamin Franklin's Science. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06659-5.

- Coulson, Thomas (1950). Joseph Henry, his life and work. Princeton University Press.

The atmosphere of Philadelphia gave him and his associates exceptional opportunity to exercise their skill with the electrostatic machine. As a result, many of their experiments were of an original character. The famous kite experiment enabled the Philadelphia group to established what had been surmised by others, that lightning was identical to the mild charge of electricity produced by the friction of the electrostatic machine. Franklin invented the lightning rod, which goes down in history as the first practical electrical invention.

- Crane, Verner Winslow (1954). Benjamin Franklin and a rising people. Little, Brown.

- Finger, Stanley (21 December 2012). Doctor Franklin's Medicine. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-0191-4.

- Garche, Jürgen (20 May 2013). Encyclopedia of Electrochemical Power Sources. Newnes. ISBN 978-0-444-52745-5.

- Gregory, George (1822). A Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. W.T. Robinson.

- Grimnes, Sverre (2014). Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity Basics. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-411533-0.

- Isaacson, Walter (4 May 2004). Benjamin Franklin: An American Life. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5807-4.

- Jackson, Joe (2005). A World on Fire: A Heretic, an Aristocrat, and the Race to Discover Oxygen. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03434-5.

- LeMay, J. A. Leo (1 September 1987). Benjamin Franklin: Writings. Penguin Group USA. ISBN 978-0-940450-29-5.

- Lemay, J. A. Leo (2009). The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 3: Soldier, Scientist, and Politician, 1748–1757. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4121-1.

- Lynn, Barry C. (2009). Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-55703-6.

- Maclean, John (1877). History of the College of New Jersey: From Its Origin in 1746 to the Commencement of 1854. Lippincott.

- McGrath, Kimberley A. (2001). The Gale Encyclopedia of Science: Catastrophism-Eukaryotae. Gale Group. ISBN 978-0-7876-4372-0.

- McNichol, Tom (2011). AC/DC: The Savage Tale of the First Standards War. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1-118-04702-8.

- Morgan, Edmund Sears (2003). Benjamin Franklin. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10162-1.

- Malmivuo, Jaakko; Plonsey, Robert (1995). Bioelectromagnetism: Principles and Applications of Bioelectric and Biomagnetic Fields. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505823-9.

- Pasles, Paul C. (2008). Benjamin Franklin's Numbers: An Unsung Mathematical Odyssey. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12956-8.

- Pyenson, Lewis; Gauvin, Jean-François (2002). The Art of Teaching Physics: The Eighteenth-century Demonstration Apparatus of Jean Antoine Nollet. Les éditions du Septentrion. ISBN 978-2-89448-320-6.

- Schafer, Larry E. (1992). Taking Charge: An Introduction to Electricity. NSTA Press. ISBN 978-0-87355-110-6.

- Schiffer, Michael B. (2003). Draw the Lightning Down: Benjamin Franklin and Electrical Technology in the Age of Enlightenment. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23802-8.

- Schofield, Robert E. (1 January 1997). The Enlightenment of Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1733 to 1773. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-04083-1.

- Talbott, Page (June 2009). Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World. DIANE Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4379-6732-6.

- Tucker, Tom (1 April 2009). Bolt Of Fate: Benjamin Franklin and His Fabulous Kite. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-0-7867-3942-4.

- Waldstreicher, David (10 August 2005). Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-8090-8315-2.

External links

- Benjamin Franklin's electrical apparatus (electrostatic machine) at Smithsonian National Museum of American History

- The Amazing Adventures of Ben Franklin – Scientist & Inventor / Opposites Attract with picture of glass globe on top

- Franklin's Electrostatic Generator information and picture from University of Maryland Electrical and Computer Engineering Dept.