Falls Church, Virginia

| Falls Church, Virginia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Independent city | ||

| City of Falls Church | ||

|

A view off Broad Street (Route 7) | ||

| ||

Falls Church  Falls Church  Falls Church | ||

| Coordinates: 38°52′56″N 77°10′16″W / 38.88222°N 77.17111°WCoordinates: 38°52′56″N 77°10′16″W / 38.88222°N 77.17111°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| State |

| |

| County | None (Independent city) | |

| Settled | c. 1699 | |

| Incorporated (town) | 1875 | |

| Incorporated (city) | 1948 | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Council–manager | |

| • Mayor | David Tarter | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 2.0 sq mi (5.2 km2) | |

| • Land | 2.0 sq mi (5.2 km2) | |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) | |

| Elevation | 325 ft (99 m) | |

| Population (2010) | ||

| • Total | 12,332 | |

| • Estimate (2015) | 13,892 | |

| • Density | 6,950/sq mi (2,683.5/km2) | |

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | |

| ZIP codes | 22040, 220142, 22044, 22046 | |

| Area code(s) | 703 and 571 | |

| FIPS code | 51-27200 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 1495526[1] | |

| Website |

fallschurchva | |

| Sister city is Kokolopori, Democratic Republic of Congo | ||

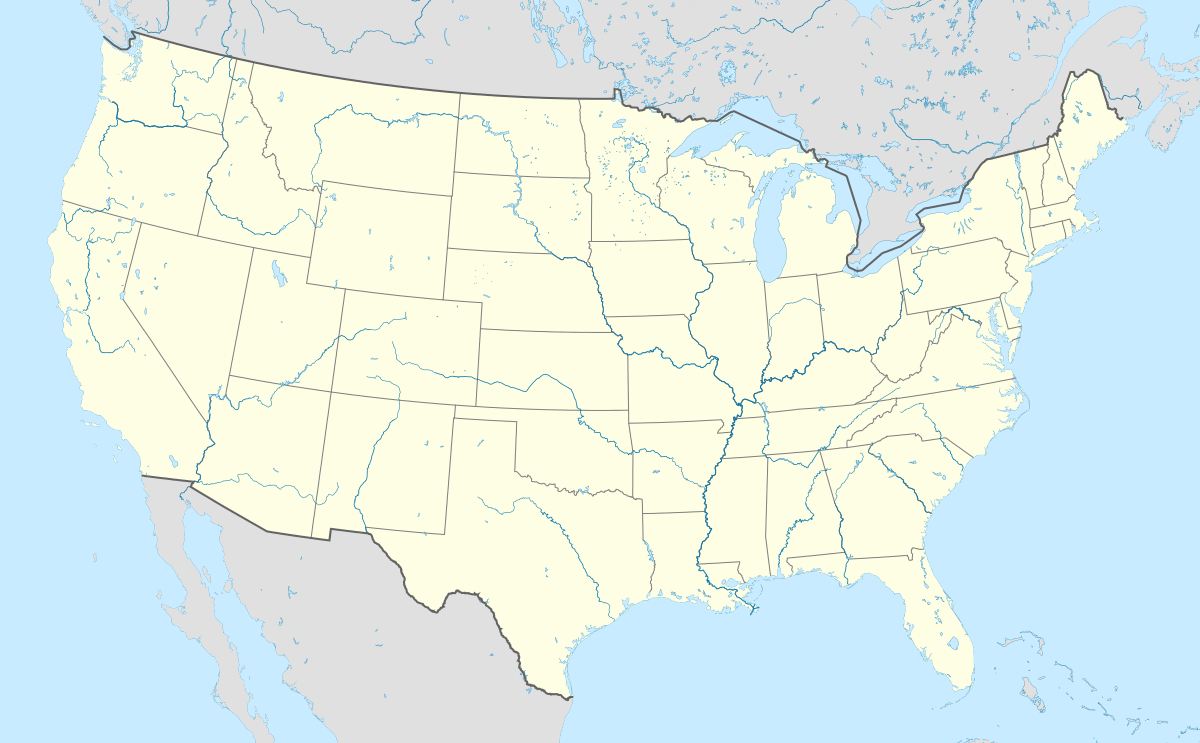

Falls Church is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 12,332.[2] The estimated population in 2015 was 13,892.[3]

Falls Church is included in the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Taking its name from The Falls Church, an 18th-century Anglican parish, Falls Church gained township status within Fairfax County in 1875. In 1948, it was incorporated as the City of Falls Church, an independent city with county-level governance status.[4] It is also referred to as Falls Church City.

The city's corporate boundaries do not include all of the area historically known as Falls Church; these areas include portions of Seven Corners and other portions of the current Falls Church postal districts of Fairfax County, as well as the area of Arlington County known as East Falls Church, which was part of the town of Falls Church from 1875 to 1936.[5] For statistical purposes, the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the City of Falls Church with Fairfax City and Fairfax County.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Falls Church has the lowest level of poverty of any independent city or county in the United States.[6]

History

When the City of Falls Church was incorporated in 1948, its boundaries included only the central portion of the area historically known as Falls Church;[7] those other areas, often still known as Falls Church (although they lie in Fairfax and Arlington counties), are considered here for historical reasons.

Sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the area of present-day Falls Church was part of the Algonquian-speaking world, outside the fringes of the powerful Powhatan paramount chiefdom to the south. It was part of the Anacostan chiefdom, centered on the lower Anacostia River near present-day Washington, DC. (John Smith visited them in 1608.) The Anacostans were organized under the Piscataway paramount chiefdom (not part of the Powhatan alliance), which by the 1630s claimed to have had thirteen successive rulers.[8] Tauxenent/Doegs, who had shifted politically from Powhatan's alliance to Iroquois alliances,[9] migrated into the Piscataway territories in the 1660s.[10]

The earliest known settlement within the current city limits of Falls Church (whether Anacostan or Doeg is unclear) was on the south side of present-day N. Washington Street at its intersection with Columbia Street.[11][12] Just east of Falls Church, on Wilson Boulevard, is Powhatan Springs,[13] where Powhatan is said to have convened autumn councils.[14] Today's Broad Street and Great Falls Street follow long-established trade and communication routes.[15]

In the late 17th century, especially after Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, English settlers from the Tidewater region of Virginia began to migrate to the area. According to local tradition, one of the chimneys of the "Big Chimneys" house and tavern was inscribed "1699"; based on this claim, 1699 is often taken to be the first European settlement in the immediate vicinity.[16] (The house site is now Big Chimneys Park, on W. Annandale Road north of S. Maple.)

Eighteenth century

The Falls Church, from which the city takes its name, was first called "William Gunnell's Church", and built of wood in 1733 to serve the western part of Truro Parish, which had been formed two years earlier from a larger parish centered near Quantico. By 1757, the building was referred to as "The Falls Church", reflecting its location near the main tobacco rolling road circumventing the Little Falls of the Potomac River. George Mason became a vestryman in 1748, as did his neighbor George Washington in 1763.[17] In 1769, a brick church designed by James Wren (who later designed the Fairfax County Courthouse) replaced the wooden one, at which point the new Falls Church became the seat of the newly formed Fairfax Parish, with the eastern portion of the former parish (nearer Mason's and Washington's residences) becoming Pohick Church.[18] However, following the Revolution, the Commonwealth of Virginia disestablished the Anglican Church, and it lost tax support (and many ministers had also left due to British loyalties, although those that remained formed the Episcopal Church). In 1789, The Falls Church was abandoned,[19] and the Wren-designed building was only re-occupied again by an Episcopal congregation in 1836; that congregation continues to this day.[20] Nearly a decade later, in 1843, Truro Church was founded to serve Episcopalians in Fairfax City.

Around 1776, Methodism came to the area, with religious services held at "Church Hill", a home about a mile east of the Falls Church near Seven Corners. A chapel known as Adam's Chapel or Fairfax Chapel had been built on what later became Oakwood Cemetery by 1779, and iterant black Methodist preacher Harry Hosier preached there in 1781.[21] The Methodist chapel (replaced by a brick structure in 1819) continued in service until torn down by Union troops in 1862.[22] In 1869, it was rebuilt nearby by Southern sympathizers as Dulin United Methodist Church, and expanded in 1892 and 1926.[23] Meanwhile, African American Methodists had been meeting secretly at the home of ex-slaves on the Dulany plantation, and were encouraged by white minister Rev. Hiram Reed to form their own church, so with the help of a white former Union Army officer who purchased land on their behalf in 1867, and later with timber donated by William Y. Dulin (former owner of several members), they formed Galloway Chapel, which later became Galloway United Methodist Church.[24]

Nineteenth century

Falls Church, like many colonial Virginia settlements, began as a "neighborhood" of large land grant plantations anchored by an Anglican church. By 1800, the large land holdings had been subdivided into smaller farms, many of them relying on enslaved labor. With the soil exhausted by tobacco, new crops including wheat, corn, potatoes, and fruit were grown for area markets.[25] At the same time, the movement of the nation's capital from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., in 1800 brought a gradual influx of workers to nearby Falls Church.[26] Taverns also opened to serve travelers going to and from the federal district.

By the start of the Civil War, Falls Church had seen an influx of Northerners seeking land and better weather. Thus the township's vote for Virginian secession was about 75% for, 25% against. The town changed hands several times during the early years of the war. Confederate General James Longstreet was headquartered at Home Hill (now the Lawton House on Lawton Street) following the First Battle of Manassas. The earliest known instance of U.S. wartime aerial reconnaissance was carried out from Taylor's Tavern at Seven Corners by aeronaut Thaddeus S. C. Lowe of the Union Army Balloon Corps. When Confederates took Falls Church, the town became one of the earliest targets of aerially-directed bombardment, with Lowe operating air reconnaissance from Arlington Heights and directing Union guns near the Chain Bridge by telegraph. These events have now been documented extensively, particularly the military encampments on Minor's Hill and Upton's Hill.[27][28]

Julia Ward Howe was inspired to write "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" after observing a review of Federal troops at Upton's Hill in Falls Church with her husband and friends on May 28, 1861.[29] She had witnessed the troops singing "John Brown's Body" and spent the next morning beginning to develop the lyrics she would eventually set to that same tune and publish in The Atlantic in 1862.[30]

Following Reconstruction, Falls Church remained a rural farm community. It gained township status in 1875. Its first mayor after this status change was Dr. John Joseph Moran, known as the attending physician when Edgar Allan Poe died.[31]

In 1887, the town of Falls Church retroceded to Fairfax County the section south of what is now Lee Highway, then known as "the colored settlement".[32]

Twentieth century

By 1900, Falls Church was the largest town in Fairfax County, with 1,007 residents.[33] Many of the residents at that time had come from the northern states or elsewhere. A 1904 map of the town shows 125 homes and 38 properties from two to 132 acres (0.53 km2). The town had become a center of commerce and culture, with 55 stores and offices and seven churches.[33] In 1915 the town had a population of 1,386 (88% white, 12% black).[34]

In 1912 the Commonwealth allowed municipalities to enact residential segregation, and Falls Church's town council soon passed an ordinance designating a colored residential district, in which whites were not allowed to live and outside of which blacks were not allowed to live; black property owners already living outside that district did not have to move, but could only sell to whites.[34] The Colored Citizen's Protective League formed in opposition to this ordinance and worked to prevent it from being enforced. The League incorporated as the first rural chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1915. In November 1917 the segregation law was formally nullified by the United States Supreme Court, though the Falls Church City Council did not formally repeal it until February 1999.[35]

In 1948, Falls Church became an independent city in order, according to the city's website, "to establish a highly acclaimed school system."[36] The existing system was racially segregated, as was common at the time.[37][38] (See "Cultural Events," below, for more on Falls Church's history of segregation. Also note the naming of the middle school after Mary Ellen Henderson in a belated effort to make amends.) Following the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, one city school board member pushed to allow black students to attend Falls Church city schools (they attended Fairfax County schools, with the city paying tuition to the county), but others delayed, and the state government's "Massive Resistance" laws (known as the Stanley plan) prevented desegregation of any schools.[32] In the 1959 school board elections, candidates supported by the Citizens for a Better Council, which lobbied for increased school funding overall, won the majority of the school board. These more progressive school board members then allowed "pupil placement" of selected black students into Falls Church schools as allowed by Virginia's 1959 freedom of choice law. Three students applied for fall 1961, two for Mason High School and one for Madison Elementary; all were approved and attended city schools that fall. In 1963, one of these Mason students helped gain full desegregation for the State Theatre, on Washington Street, which had previously excluded black patrons.[39][40]

Twenty-first century

In 2014, the Falls Church boundary expanded to include an additional 38.4 acres (15.5 ha) of what was Fairfax County, from the sale of the Falls Church Water Utility to Fairfax Water.[41]

Northern Virginia is home to a sizable Vietnamese-American community that began to develop with immigration from South Vietnam after the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. One visible sign of this community is Eden Center, a Vietnamese-American shopping plaza constructed in 1984 in the southeast corner of Falls Church, at Seven Corners, and marked by a traditional gateway, guardian lions, and a clock tower modeled on one in Saigon. It houses restaurants, bakeries, and shops.[42][43]

Historic sites

Cherry Hill Farmhouse and Barn, an 1845 Greek-Revival farmhouse and 1856 barn, owned and managed by the city of Falls Church, are open to the public select Saturdays in summer.[44]

Tinner Hill Arch and Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation represent a locus of early African American history in the area, including the site of the first rural chapter of the NAACP.

Two of the District of Columbia's original 1791 boundary stones (see: Boundary Markers of the Original District of Columbia) are located in public parks on the boundary between Falls Church and Arlington County. The West Cornerstone stands in Andrew Ellicott Park at 2824 Meridian Street, Falls Church[45]/N. Arizona Street, Arlington, just south of West Street.[46][47] Stone number SW9 stands in Benjamin Banneker Park on Van Buren Street, south of 18th Street, near the East Falls Church Metro station. (Most of Banneker Park is in Arlington County, across Van Buren Street from Isaac Crossman Park at Four Mile Run).[46][48][49]

- Sites on the National Register of Historic Places

| Site | Year built | Address | Listed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birch House (Joseph Edward Birch House) | 1840 | 312 East Broad Street | 1977 |

| Cherry Hill (John Mills Farm) | 1845 | 312 Park Avenue | 1973 |

| The Falls Church | 1769 | 115 East Fairfax Street | 1970 |

| Federal District Boundary Marker, SW 9 Stone | 1791 | 1976 | |

| Federal District Boundary Marker, West Cornerstone | 1791 | 2824 Meridian Street | 1991 |

| Mount Hope | 1790s | 203 South Oak Street | 1984 |

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.0 square miles (5.2 km2), all of its land.[50] Falls Church is the smallest independent city by area in Virginia. Since independent cities in Virginia are considered county-equivalents, it is also the smallest county-equivalent in the United States by area.

The center of the city is the crossroads of Virginia State Route 7 (Broad St./Leesburg Pike) and U.S. Route 29 (Washington St./Lee Highway).

Tripps Run, a tributary of the Cameron Run Watershed, drains two-thirds of Falls Church, while the Four Mile Run watershed drains the other third of the city. Four Mile Run flows at the base of Minor's Hill, which overlooks Falls Church on its north, and Upton's Hill, which bounds the area to its east.[51]

Major highways

- VA 7

- VA 237

- VA 338

- US 29

- SR 649

- SR 694

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 660 | — | |

| 1890 | 792 | 20.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,007 | 27.1% | |

| 1910 | 1,128 | 12.0% | |

| 1920 | 1,659 | 47.1% | |

| 1930 | 2,019 | 21.7% | |

| 1940 | 2,576 | 27.6% | |

| 1950 | 7,535 | 192.5% | |

| 1960 | 10,192 | 35.3% | |

| 1970 | 10,772 | 5.7% | |

| 1980 | 9,515 | −11.7% | |

| 1990 | 9,578 | 0.7% | |

| 2000 | 10,377 | 8.3% | |

| 2010 | 12,332 | 18.8% | |

| Est. 2015 | 13,892 | [3] | 12.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[52] 1790-1960[53] 1900-1990[54] 1990-2000[55] 2010-2013[56] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[57] of 2010, Falls Church City had a population of 12,332. The population density was 6,169.1 people per square mile. There were 5,496 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 80.6% White, 5.3% Black or African American, 0.5% Native American, 9.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, and 4.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 9.5% of the population.

In the city the population was spread out with 7.3% under the age of five, 26.6% under the age of 18, and 11.6% over the age of 65. The percentage of the population that were female was 51%. 74.4% of the population had a bachelor's degree or higher (age 25+).

The median income for a household in the city was $120,000, with 4% of the population below the poverty line, the lowest level of poverty of any independent city or county in the United States.

2000 census

As of the census[58] of 2000, there were 10,377 people, 4,471 households, and 2,620 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,225.8 people per square mile (2,013.4/km²). There were 4,725 housing units at an average density of 2,379.5/sq mi (916.8/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 84.97% White, 3.28% Black or African American, 0.24% Native American, 6.50% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islander, 2.52% from other races, and 2.43% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.44% of the population.

There were 4,471 households out of which 30.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them; 47.1% were married couples living together, 8.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.4% were non-families. 33.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city the population was spread out with 23.4% under the age of 18, 5.1% from 18 to 24, 31.1% from 25 to 44, 28.1% from 45 to 64, and 12.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 94.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $74,924, and the median income for a family was $97,225. Males had a median income of $65,227 versus $46,014 for females. The per capita income for the city was $41,051. About 2.8% of families and 4.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.3% of those under age 18 and 4.1% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Falls Church is governed by a seven-member city council, each elected at large for four-year, staggered terms.[59] Council members are typically career professionals holding down full-time jobs.[59] In addition to attending a minimum of 22 council meetings and 22 work sessions each year, they also attend meetings of local boards and commissions and regional organizations (several Council Members serve on committees of regional organizations as well).[59] Members also participate in the Virginia Municipal League and some serve on statewide committees.[59] The mayor is elected by members of the council.[59] The city operates in a typical council-manager form of municipal government, with a city manager hired by the council to serve as the city's chief administrative officer.[59] The city's elected Sheriff is S. Steven Bittle.

Candidates for city elections typically do not run under a nationally affiliated party nomination.[59]

City services and functions include education, recreation and parks, library, police, land use, zoning, and building inspections, street maintenance, and storm water and sanitary sewer service. Often named a Tree City USA, the city has one full-time arborist. Some public services are provided by agreement with the city's county neighbors of Arlington and Fairfax, including certain health and human services (Fairfax); and court services, transport, and fire/rescue services (Arlington).

The city provided water utility service to a large portion of eastern Fairfax County, including the dense commercial areas of Tysons Corner and Merrifield, until January, 2014, when the water utility was sold to the Fairfax County Water Authority.[60]

Economy

In 2011, Falls Church was named the richest county in the United States, with a median annual household income of $113,313.[61] While Fortune 500 companies Computer Sciences Corporation,[62] General Dynamics,[63] and Northrop Grumman[64] have headquarters addressed in Falls Church, they are physically in Fairfax County.

ENSCO, Inc. is in Fairfax County but has a Falls Church address.[65][66]

Top employers

According to the city's 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[67] the top employers in the City are:

| Employer | Employees |

|---|---|

| Falls Church City Public Schools | 559 |

| City of Falls Church | 337 |

| Kaiser Permanente | 265 |

| Koon's Ford & Nissan | 204 |

| BG Healthcare Services | 202 |

| Tax Analysts | 182 |

| VL Home Health Care, Inc | 160 |

| Giant Food Store | 130 |

| Care Options | 127 |

Education

The city is served by Falls Church City Public Schools:

- Jessie Thackrey Preschool

- Mount Daniel Elementary School, which includes kindergarten and first grade.

- Thomas Jefferson Elementary School, which includes grades 2–5.

- Mary Ellen Henderson Middle School, which includes grades 6–8.

- George Mason High School, which includes grades 9–12.

Of these four Falls Church City Public Schools, one, Mount Daniel Elementary School, is located outside city limits in neighboring Fairfax County.[68] Falls Church High School is not part of the Falls Church City Public School system, but rather the Fairfax County Public School system; it does not serve the city of Falls Church.

Falls Church City is eligible to send up to three students per year to the Fairfax County magnet school, Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology.[69]

The city is home to Saint James Catholic School, a parochial school serving grades K–8.

Transportation

Although two stations on the Washington Metro's Orange Line have "Falls Church" in their names, neither lies within the City of Falls Church: East Falls Church is in Arlington County and West Falls Church is in Fairfax County.

- Metro's Silver Line, completed July 2014, serves the East Falls Church station. It runs between Largo Town Center in the east, following the Blue Line route to Stadium-Armory, the Orange and Blue Lines to Rosslyn, and finally the Orange route alone until it reaches East Falls Church, where it branches off towards the northwest, currently terminating at the Wiehle-Reston East station. The next phase of the Silver Line will eventually reach eastern Loudoun County, including a station at Dulles International Airport. East Falls Church is the westernmost designated transfer station.

- The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority provides bus service throughout the Washington metropolitan area, including Falls Church.

- A small portion of the 45-mile (72 km) Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Trail (W&OD Trail) runs through the City (see: Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Regional Park). The trail enters the City from the west between mile markers 7 and 7.5 (near Broad Street). The trail enters the city from the east between mile markers 5.5 and 6. The W&OD Trail travels on the rail bed of the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad and various predecessor lines, which provided passenger service from 1860 to May 31, 1951, with exception of a few years during the U.S. Civil War. Freight service was abandoned when the railroad closed in August 1968. The Four Mile Run Trail, which ends at an intersection with the Mount Vernon Trail near Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, begins in the city at Van Buren Street. These trails comprise a major bicycle commuting route to Washington, D.C.

From 1948 to 1960, Falls Church was the home of Falls Church Airpark, a general aviation airport located along U.S. Route 50, west of Seven Corners. The facility's 2,650 foot unpaved runway was used extensively by private pilots and civil defense officials. Residential development, multiple accidents, and the demand for retail space led to its closure in 1960.[70][71][72]

News and media

The Falls Church News-Press is a free weekly newspaper founded in 1991 that focuses on local news and commentary and includes nationally syndicated columns.[73]

The area is also served by national and regional newspapers, including The Washington Examiner, The Washington Times, and The Washington Post. The City is also served by numerous citizen- and corporate-sponsored Internet blogs.

WAMU Radio 88.5 produces several locally oriented news and opinion programs.

Culture

- Annual events

Memorial Day Parade. Held since at least the 1950s, with bands, military units, civic associations, and fire/rescue stations, in recent years the event has featured a street festival with food, crafts, and non-profit organization booths, and a 3k fun run (the 2009 race drew some 3,000 runners).[74]

Falls Church Farmer's Market is held Saturdays year-round, Jan. 3 – April 25 (9 am – Noon), May 2 – Dec. 26 (8 am – Noon), at the City Hall Parking Lot, 300 Park Ave. In addition to regional attention,[75] in 2010 the market was ranked first in the medium category of the American Farmland Trust's contest to identify America's Favorite Farmers' Markets.[76]

- Cultural institutions

The Falls Church Village Preservation and Improvement Society was originally founded in 1885 by Arthur Douglas and re-established in 1965 to promote the history, culture, and beautification of the city.

The Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation was founded in 1997 by Edwin B. Henderson, II to preserve the Civil Rights and African American history and culture. Falls Church is where the first rural branch of the NAACP was established stemming from events that took place in 1915, when the town attempted to pass a segregation ordinance by creating segregated districts in the town. The ordinance was not enforced after the U. S. Supreme Court ruling on Buchanan versus Warley, in 1917.

The Mary Riley Styles Public Library, 120 N. Virginia Ave., is Falls Church's public library; established in 1928, its current building was constructed for the purpose in 1958 and expanded in 1993.[77] In addition to its circulating collections, it houses a local history collection, including newspaper files, local government documents, and photographs.

The State Theatre, 220 North Washington St., stages a wide variety of live performances. Built as a movie house in 1936, it was reputed to be the first air-conditioned theater on the east coast. It closed in 1983; after extensive renovations in the 1990s, including a stage, bar, and restaurant, it re-opened as a music venue.[78]

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Falls Church has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[79]

Notable people

- Golnar Adili (1976), multidisciplinary artist[80]

- Tommy Amaker (1965), current head men's basketball coach at Harvard University

- Allan Bridge, conceptual artist

- Jane Brucker, actress and screenwriter

- Jayme Cramer, backstroke and butterfly swimmer

- Nick Galifianakis, cartoonist

- John Hartman, musician and founding member of The Doobie Brothers

- Molly Henneberg, news reporter

- Mike Hindert, bass guitarist

- Louisa Krause, actress

- Nancy Kyes, film and television actress

- Matthew F. McHugh, former US congressman

- Kyle E. McSlarrow, former Deputy Secretary of the United States Department of Energy

- Alixa Naff, historian[81]

- Joseph Harvey Riley, ornithologist

- Eric Schmidt (1955), Executive Chairman & former CEO of Google, former CEO of Novell, 138th-richest person in the world in 2012[82]

- Mohamed Soltan, political activist

- Fred Talbot (1941–2013), professional baseball player[83]

See also

References

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Falls Church city, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- 1 2 "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Municipal Code of the City of Falls Church: Incorporation and Boundaries". Library1.municode.com:80. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ Gernard and Netherton, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited, p.65.

- ↑ "Table 1: 2011 Poverty and Median Income Estimates - Counties". Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. 2011.

- ↑ Gernand and Netherton, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited, p.156. This and other histories of Falls Church document numerous historical references to areas outside the current city boundaries (and even outside then-town boundaries) as part of "Falls Church."

- ↑ Wayne Clark & Helen Rountree, "The Powhatans and the Maryland Mainland," in Powhatan Foreign Relations, 1500–1722 (Univ. Press of Virginia, 1993), pp.114 (fig. 5.2), 115.

- ↑ "Early Virginia (Powhatan's Territory in 1607), map, Powhatan Museum of Indigenous Arts and Culture". Powhatanmuseum.com. December 13, 2006. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ Wayne Clark & Helen Rountree, "The Powhatans and the Maryland Mainland," in Powhatan Foreign Relations, 1500–1722 (Univ. Press of Virginia, 1993), p.118.

- ↑ Melvin Lee Steadman, Jr., Falls Church: By Fence and Fireside (Falls Church Public Library, 1964), p. 3.

- ↑ Samuel V. Poudfit, "Ancient Village Sites and Aboriginal Workshops in the District of Columbia," American Anthropologist (Anthropological Society of Washington), 2.3 (July 1889): 243.

- ↑ "A Pictorial History of Arlington, Area C Neighborhoods" (see Powhatan Springs) Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Steadman, Falls Church, p. 2.

- ↑ History of Falls Church Archived August 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Gernand & Netherton, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited, pp. 7, 19.

- ↑ Steadman, Falls Church by Fence and Fireside, pp. 15, 16–17, 37.

- ↑ Steadman, 13.

- ↑ Steadman, p.25

- ↑ "Joan R. Gundersen, PhD, "How 'Historic' Are Truro Church and The Falls Church?" Dec. 22, 2006". Jrgundersen.name. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ Netherton, Nan. Fairfax County, Virginia: A History, p. 233. Fairfax County Board of Supervisors, 1978.

- ↑ Gernand and Netherton, Falls Church, pp. 31–32, 42, citing Froncek, The City of Washington, pp. 48–49

- ↑ http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=2841

- ↑ http://www.gallowayumchurch.org/#!history/c1xu8

- ↑ Images of America: Victorian Falls Church, The Victorian Society at Falls Church, 2007, page 7.

- ↑ All-American Crossroads, Jean Rust, 1970, p. 11.

- ↑ ""Balloons in the American Civil War," U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission". centennialofflight.net. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ Gernand and Netherton, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited, 47–48; Bradley E. Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War--Falls Church During the Civil War.

- ↑ Connery, William S. (2011). Civil War Northern Virginia 1861. Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 104.

- ↑ Herbert, Paul N. (2009). God Knows All Your Names: Stories in American History. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. p. 139.

- ↑ Bandy, W.T. "Dr. Moran and the Poe-Reynolds Myth", in Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987. pp. 34–5

- 1 2 "Darian Bates, "Meeting John A. Johnson: Unsung Hero in Falls Church's 1950s Struggle to Integrate Its Schools," Falls Church News-Press 15.30 (Sept. 29-Oct. 5, 2005)". Fcnp.com. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- 1 2 Images of America: Victorian Falls Church, The Victorian Society at Falls Church, 2007, page 101.

- 1 2 Images of America: Victorian Falls Church, The Victorian Society at Falls Church, 2007, p. 125

- ↑ "Darian Bates, "Mary Ellen 'Nellie' Henderson: A Life of Making Differences, Big and Small," Falls Church News-Press, Feb. 17, 2005". Fcnp.com. February 17, 2005. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ "About Falls Church". Fallschurchva.gov. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ The Falls Church NAACP Archived February 27, 2004, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Images of America: Victorian Falls Church, The Victorian Society at Falls Church, 2007, page 8.

- ↑ "Darian Bates, "M.E. Costner Leads First Class of Black Students Following Approval by Falls Church School Board," Falls Church News-Press 15.31 (Oct. 6–12, 2005)". Fcnp.com. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ On the 1959 state law, see James H. Hershman Jr., "Massive Resistance Meets Its Match: The Emergence of a Pro-Public School Majority," in The Moderates' Dilemma: Massive Resistance to School Desegregation in Virginia, eds. Matthew Lassiter & Andrew Lewis (Univ. Press of Virginia, 1998), pp. 127–132.

- ↑ "3-Judge Panel Gives Final OK to Terms of F.C. Water System Sale". Falls Church News-Press. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ Jessica Meyers, "Pho and Apple Pie: Eden Center as a Representation of Vietnamese American Ethnic Identity in the Washington, D.C., Metropolitan Area, 1975–2005," Journal of Asian American Studies 9.1 (2006): 55–85.

- ↑ "Eden Center Web site". Edencenter.com. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ "About Cherry Hill". Friends of Cherry Hill Foundation, Inc. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ↑ Steadman, Falls Church by Fence & Fireside, 9.

- 1 2 "Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia". Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ↑ "Andrew Ellicott Park at the West Cornerstone" in official website of Arlington County, Virginia. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Benjamin Banneker Park" in official website of Arlington County, Virginia. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Isaac Crossman Park at Four Mile Run" in official website of Arlington County, Virginia. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "The Hills and Valleys of Falls Church". Fallschurchenvironment.org. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "About the City Council". Fallschurchva.gov. July 14, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ "City Agrees to Sell Water System to Fairfax".

- ↑ Vardi, Nathan "America's Richest Counties", Forbes, April 11, 2011, accessed June 6, 2011.

- ↑ "CSC Global Locations". Computer Sciences Corporation.

- ↑ Contacts. General Dynamics. Retrieved on August 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Locations" Northrop Grumman. Retrieved on August 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Office locations." ENSCO, Inc. Retrieved on April 2, 2015. "Falls Church, Virginia 3110 Fairview Park Drive, Suite 300 Falls Church, Virginia 22042-4501"

- ↑ "Annandale CDP, Virginia" (Archive). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on April 2, 2015. "2010 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Annandale CDP, VA"

- ↑ "2013 financials" (PDF). City of Falls Church, VA. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ Barton, Mary Ann. "It's Official: Fairfax Water Purchases Falls Church Water System for $40 Million" (Archive). Falls Church Patch. Retrieved on May 2, 2015. "This agreement also included a boundary adjustment that transferred 38.4 acres of land into the City of Falls Church. The largest parcel includes the 36 acres on which the City's George Mason High School and Mary Ellen Henderson Middle School sit."

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology

- ↑ Freeman, Paul "Falls Church Airpark, Falls Church, VA" Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields. Retrieved March 19, 2014

- ↑ Rollo, Vera (2003) Virginia Airports : A Historical Survey of Airports and Aviation From the Earliest Days. Richmond, VA: Virginia Aviation Historical Society

- ↑ Day, Kathleen (September 21, 1987) "Small Airports Nosediving in Number" The Washington Post, page B1

- ↑ "The Publisher: Q&A with Falls Church News-Press Owner-Editor Nicholas F. Benton," Out Front Blog, July 7, 2009 Archived February 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Article in ''Falls Church News-Press'', May 2009". Fcnp.com. May 28, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Stephanie Willis, "Falls Church Farmer's Market," D.C. Foodies, Feb. 2, 2009". Dcfoodies.com. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ "American Farmland Trust: Current Top 20 America's Favorite Farmers Markets". Action.farmland.org. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ Mary Riley Styles Public Library – History

- ↑ "The State Theatre – History". Thestatetheatre.com. November 27, 1988. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Climate Summary for Falls Church, Virginia". Weatherbase.

- ↑ "Golnar Adili". Victori Contemporary. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ Barakat, Matthew (2013-06-05). "Arab-American scholar Alixa Naff dies at 93". Associated Press. Seattle Times. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- ↑ Esposito, Greg (November 10, 2006). "Google CEO gives Va. Tech $2 million –". Roanoke.com. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Death Notice: FREDERICK L. TALBOT", The Washington Post, January 16, 2013

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Falls Church, Virginia. |

-

Falls Church travel guide from Wikivoyage

Falls Church travel guide from Wikivoyage - Official website

-

Geographic data related to Falls Church, Virginia at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Falls Church, Virginia at OpenStreetMap - City of Falls Church at the Wayback Machine (archived November 3, 2005)

- City of Falls Church at the Wayback Machine (archived February 18, 2001)

|

Fairfax County |  | ||

| Fairfax County | |

Arlington County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Fairfax County |