Experience curve effects

In management, models of the learning curve effect and the closely related experience curve effect express the relationship between equations for experience and efficiency or between efficiency gains and investment in the effort.

Learning curve and learning curve effect

"Learning curves" were first observed by the 19th century German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus investigating the difficulty of memorizing varying numbers of verbal stimuli. Subsequent learning about the complex processes of learning are discussed in the Learning curve article.

Experience shows that the more times a task has been performed, the less time is required on each subsequent iteration. This relationship was probably first quantified in 1936 at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in the United States,[1] where it was determined that every time total aircraft production doubled, the required labour time decreased by 10 to 15 percent. Subsequent empirical studies from other industries have yielded different values ranging from only a couple of percent up to 30%, but in most cases it is a constant percentage: It did not vary at different scales of operation. The Learning Curve model posits that for each doubling of the total quantity of items produced, costs decrease by a fixed proportion, as described by Equations 1 and 2. The equations have the same equation form. The two equations differ only in the definition of the Y term, but this difference can make a significant difference in the outcome of an estimate.

Unit Curve

This equation describes the basis for what is called the unit curve. In this equation, Y represents the cost of a specified unit in a production run. For example, If a production run has generated 200 units, the total cost can be derived by taking the equation below and applying it 200 times (for units 1 to 200) and then summing the 200 values. This is cumbersome and requires the use of a computer or published tables of predetermined values. [The following information may be helpful: When the equation for Yx below is associated with a unit improvement curve it is called a Crawford unit curve. When exactly the same equation for Yx below is called a cumulative average learning curve, it is called a Wright cumulative average. To calculate a Wright xth unit cost, Px, from its cumulative average, we have

because in this case

Now the equation for the unit curve is given by:[2]

where

- K is the number of direct labour hours to produce the first unit

- Yx is the number of direct labour hours to produce the xth unit

- x is the unit number

- b is the learning percentage (expressed as a decimal)

Cumulative Average Curve

This equation describes the basis for the cumulative average or cum average curve. In this equation, Y represents the average cost of different quantities (X) of units. The significance of the "cum" in cum average is that the average costs are computed for X cumulative units. Therefore, the total cost for X units is the product of X times the cum average cost. For example, to compute the total costs of units 1 to 200, an analyst could compute the cumulative average cost of unit 200 and multiply this value by 200. This is a much easier calculation than in the case of the unit curve.

where

- K is the number of direct labour hours to produce the first unit

- Yx is the average number of direct labour hours to produce first x units

- x is the unit number

- b is the learning percentage

The experience curve

Generally the production of any good or service shows the experience curve effect. Each time cumulative volume doubles, value added costs (including administration, marketing, distribution, and manufacturing) fall by a constant percentage.

The Experience Curve was developed by Bruce D. Henderson and the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) while analyzing overall cost behavior in the 1960s.[3] In 1968, Henderson and BCG began to emphasize the implications of the experience curve for strategy.[4] Research by BCG in the 1960s and 70s observed experience curve effects for various industries that ranged from 10 to 25 percent.[5]

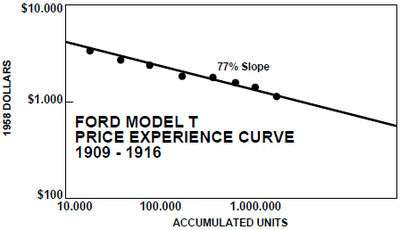

These effects are often expressed graphically. The curve is plotted with the cumulative units produced on the horizontal axis and unit cost on the vertical axis. A curve showing a 15% cost reduction for every doubling of output is called an “85% experience curve”, indicating that unit costs drop to 85% of their original level.

The experience curve is described by a power law function sometimes referred to as Henderson's Law:[6]

where:

- C1 is the cost of the first unit of production

- Cn is the cost of the n-th unit of production

- n is the cumulative volume of production

- a is the elasticity of cost with regard to output

Reasons for the effect

Examples

NASA quotes the following experience curves:[7]

- Aerospace 85%

- Shipbuilding 80-85%

- Complex machine tools for new models 75-85%

- Repetitive electronics manufacturing 90-95%

- Repetitive machining or punch-press operations 90-95%

- Repetitive electrical operations 75-85%

- Repetitive welding operations 90%

- Raw materials 93-96%

- Purchased Parts 85-88%

The primary reason for why experience and learning curve effects apply, of course, is the complex processes of learning involved. As discussed in the main article, learning generally begins with making successively larger finds and then successively smaller ones. The equations for these effects come from the usefulness of mathematical models for certain somewhat predictable aspects of those generally non-deterministic processes. They include:

- Labour efficiency - Workers become physically more dexterous. They become mentally more confident and spend less time hesitating, learning, experimenting, or making mistakes. Over time they learn short-cuts and improvements. This applies to all employees and managers, not just those directly involved in production.

- Standardization, specialization, and methods improvements - As processes, parts, and products become more standardized, efficiency tends to increase. When employees specialize in a limited set of tasks, they gain more experience with these tasks and operate at a faster rate.

- Technology-Driven Learning - Automated production technology and information technology can introduce efficiencies as they are implemented and people learn how to use them efficiently and effectively.

- Better use of equipment - as total production has increased, manufacturing equipment will have been more fully exploited, lowering fully accounted unit costs. In addition, purchase of more productive equipment can be justifiable.

- Changes in the resource mix - As a company acquires experience, it can alter its mix of inputs and thereby become more efficient.

- Product redesign - As the manufacturers and consumers have more experience with the product, they can usually find improvements. This filters through to the manufacturing process. A good example of this is Cadillac's testing of various "bells and whistles" specialty accessories. The ones that did not break became mass-produced in other General Motors products; the ones that didn't stand the test of user "beatings" were discontinued, saving the car company money. As General Motors produced more cars, they learned how to best produce products that work for the least money.

- Network-building and use-cost reductions (network effects) - As a product enters more widespread use, the consumer uses it more efficiently because they're familiar with it. One fax machine in the world can do nothing, but if everyone has one, they build an increasingly efficient network of communications. Another example is email accounts; the more there are, the more efficient the network is, the lower everyone's cost per utility of using it.

- Shared experience effects - Experience curve effects are reinforced when two or more products share a common activity or resource. Any efficiency learned from one product can be applied to the other products. (This is related to the principle of least astonishment).

Experience curve discontinuities

The experience curve effect can on occasion come to an abrupt stop. Graphically, the curve is truncated. Existing processes become obsolete and the firm must upgrade to remain competitive. The upgrade will mean the old experience curve will be replaced by a new one. This occurs when:

- Competitors introduce new products or processes that you must respond to

- Key suppliers have much bigger customers that determine the price of products and services, and that becomes the main cost driver for the product

- Technological change requires that you or your suppliers change processes

- The experience curve strategies must be re-evaluated because

- they are leading to price wars

- they are not producing a marketing mix that the market values

Strategic consequences of the effect

The BCG strategists examined the consequences of the experience effect for businesses. They concluded that because relatively low cost of operations is a very powerful strategic advantage, firms should capitalize on these learning and experience effects. [8] The reasoning is increased activity leads to increased learning, which leads to lower costs, which can lead to lower prices, which can lead to increased market share, which can lead to increased profitability and market dominance. According to BCG, the most effective business strategy was one of striving for market dominance in this way. This was particularly true when a firm had an early leadership in market share. It was claimed that if you cannot get enough market share to be competitive, you should get out of that business and concentrate your resources where you can take advantage of experience effects and gain dominant market share. The BCG strategists developed product portfolio techniques like the BCG Matrix (in part) to manage this strategy.

Today we recognize that there are other strategies that are just as effective as cost leadership so we need not limit ourselves to this one path. See for example Porter generic strategies which talks about product differentiation and focused market segmentation as two alternatives to cost leadership. Sterman et al. show that expanding rapidly to realize experience curve benefits is a high risk strategy in dynamic markets with common features like bounded rationality and durable products.[9]

One consequence of the experience curve effect is that cost savings should be passed on as price decreases rather than kept as profit margin increases. The BCG strategists felt that maintaining a relatively high price, although very profitable in the short run, spelled disaster for the strategy in the long run. They felt that it encouraged competitors to enter the market, triggering a steep price decline and a competitive shakeout. If prices were reduced as unit costs fell (due to experience curve effects), then competitive entry would be discouraged and one's market share maintained. Using this strategy, you could always stay one step ahead of new or existing rivals.

Origins of the experience curve

Excerpts of Bruce D. Henderson's published writing describe the development of the experience curve.[10][11]

Starting in 1966, according to Henderson:

- "The Boston Consulting Group's first effort to formulate the experience curve concept was an attempt to explain cost behavior over time in a process industry. The correlation between competitive profitability and market share was strikingly apparent.[10]

- "The pattern of the learning curve was an attractive initial hypothesis to explain this. The name, Experience Curve, was selected to distinguish this cost behavior phenomenon from the well known and well documented learning curve effect. The two are related, but quite different."[10]

- BCG found there were far reaching implications based on volume changes in production.[10]

- "Semiconductors provided the evidence on which to build the experience curve concept itself. The wide variety of semiconductors offered a chance to compare differing growth rates and price decline rates in a similar environment. Price data supplied by the Electronic Industries Association was compared with accumulated industry volume. Two distinct patterns emerged.[10]

- "In one pattern, prices, in current dollars, remained constant for long periods and then began a relatively steep and long continued decline in constant dollars. In the other pattern, prices, in constant dollars, declined steadily at a constant rate of about 25 percent each time accumulated experience doubled. That was the experience curve. That was 1966."[10]

Criticisms

Some authors claim that in most organizations it is impossible to quantify the effects. They claim that experience effects are so closely intertwined with economies of scale that it is impossible to separate the two.[12] In theory we can say that economies of scale are those efficiencies that arise from an increased scale of production, and that experience effects are those efficiencies that arise from the learning and experience gained from repeated activities, but in practice the two mirror each other: growth of experience coincides with increased production. Economies of scale should be considered one of the reasons why experience effects exist. Likewise, experience effects are one of the reasons why economies of scale exist. This makes assigning a numerical value to either of them difficult.

The well travelled road effect may lead people to overestimate the effect of the experience curve.

See also

- Economies of scale

- Hermann Ebbinghaus

- Management

- Marketing strategies

- Porter generic strategies

- Strategic planning

- Gordon Moore's Law of affordable computing performance growth

- Mark Kryder's Law of magnetic disk storage growth

- Jakob Nielsen's Law of wired bandwidth growth

- Martin Cooper's Law of simultaneous wireless conversation capacity growth

- Learning-by-doing

References

- ↑ Wright, T.P., Factors Affecting the Cost of Airplanes, Journal of Aeronautical Sciences, 3(4) (1936): 122-128.

- ↑ Chase, Richard B. (2001), Operations management for competitive advantage, ninth edition, International edition: McGraw Hill/ Irwin, ISBN 0-07-118030-3

- ↑ Henderson, Bruce D. "The Experience Curve – Reviewed II: History, 1973". Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ↑ https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/Classics/strategy_the_experience_curve/ BCJ 1968

- ↑ Hax, Arnoldo C.; Majluf, Nicolas S. (October 1982), "Competitive cost dynamics: the experience curve", Interfaces, 12 (5): 50–61, doi:10.1287/inte.12.5.50.

- ↑ Grant, Robert M. (2004), Contemporary strategy analysis, U.S., UK, Australia, Germany: Blackwell publishing, ISBN 1-4051-1999-3

- ↑ Cost Models - Learning Curve Calculator

- ↑ Henderson, Bruce (1974). "The Experience Curve Reviewed: V. Price Stability" (PDF). Perspectives. The Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ↑ Strategic Dynamics with Increasing Returns and Bounded Rationality, John D. Sterman, Rebecca Henderson, Eric D. Beinhocker, and Lee I. Newman, Management Science, 53(4), April 2007, 683–696.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Henderson, Bruce D. "The Experience Curve – Reviewed II: History, 1973". Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ Henderson, Bruce D. "The Experience Curve – Reviewed I: The Concept, 1974". Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ↑ Berndt, Ernst (1990). The practice of econometrics: classic and contemporary, Chapter 3.

Further reading

- Wright, Theodore Paul (February 1936), "Learning Curve", Journal of the Aeronautical Sciences

- Hirschmann, W. (Jan–Feb 1964), "Profit from the Learning Curve", Harvard Business Review

- Consulting, Boston (1972), Perspectives on Experience, Boston, Mass

- Abernathy, William; Wayne, Kenneth (Sep–Oct 1974), "Limits to the Learning Curve", Harvard Business Review

- Kiechel, Walter III (October 5, 1981), "The Decline of the Experience Curve", Fortune

- Day, George S.; Montgomery, David Bernard (1983), "Diagnosing the Experience Curve", Journal of Marketing, 47 (Spring), doi:10.2307/1251492

- Ghemawat, Pankaj (March–April 1985), "Building Strategy on the Experience Curve", Harvard Business Review, 42

- Teplitz, C.J., ed. (1991), The Learning Curve Deskbook: A Reference Guide to Theory, Calculations, and Applications, New York: Quorum Books

- Ostwald, Phillip F. (1992), Engineering Cost Estimating (3rd ed.), Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-276627-2

- Davies, Geoffrey F. (2004), Economia: New Economic Systems to Empower People and Support the Living World, ABC Books, ISBN 0-7333-1298-5

- Le Morvan, Pierre; Stock, Barbara (2005), "Medical Learning Curves and the Kantian Ideal", Journal of Medical Ethics, 31: 513–518, doi:10.1136/jme.2004.009316

- Junginger, Martin; van Sark, Wilfried; Faaij, André (2010), Technological Learning in the Energy Sector, Lessons for Policy, Industry and Science, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84844-834-6

External links

- Cost Models - Learning Curve Calculator (Accessed May 28, 2013)

- http://fast.faa.gov/pricing/98-30c18.htm