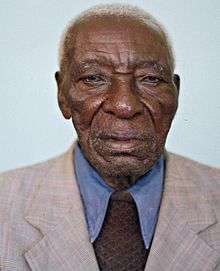

Esau Khamati Oriedo

| Esau Khamati Oriedo | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Esau Khamati Oriedo 29 January 1888 Ebwali Village, Bunyore, North Kavirondo, colonial African territory governed by Imperial British East Africa Company | ||||||||||||||||||

| Died |

1 December 1992 (aged 104) Iboona Village at Bunyore in Kenya | ||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Exclusively self-taught and functional acumen | ||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Entrepreneur, politician, soldier, religious scholar & activist, legal scholar, court interpreter & clerk, philanthropist | ||||||||||||||||||

| Years active | 1904–1992 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Organization | Kenya African Union, Kenya African National Union, Kenya Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Local Native Council of North Nyanza, Kavirondo Taxpayers Welfare Association, Kisumu Chamber of Commerce, North Kavirondo Taxpayers Association, Oriedo Self Help Society, Committee on Native Land Tenure in the North Kavirondo Reserve, Church Missionary Society Kavirondo, Anglican Church of Kenya, Church of God Kima Mission | ||||||||||||||||||

| Known for |

Valor, freedom fighter, trade unionist, philanthropist, entrepreneur, politician, culinary expert—gourmet chef, and activism (literacy and higher education, civil rights, socioeconomic and sociocultural, and religion)

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Christian | ||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Evangeline Olukhanya Ohana Analo-Oriedo (d. 11 July 1982) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

10 children

| ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Esau Khamati Oriedo (circa 1888 – 1992) was a consummate founding Kenyan statesman, freedom fighter, an anti-colonialism activist and crusader of the rights of the native peoples in the British East African Protectorate & Colony of Kenya, during the period that span more than five decades (1910s – 1960s); he was a veteran of World War I and World War II as a soldier in the King's African Rifles (KAR); politician; freedom fighter; Christian crusader and champion of religious tolerance; entrepreneur and trade unionist; a legal advocate; literacy champion; and philanthropist of the colonial and postcolonial eras.[1][2][3][4][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

In 1952 – 1957 he was detained at Kapenguria together with Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and fellow Kenyan freedom fighters reminiscent of Chief Koinange Wa Mbiyu (d. 1960).[5][10] He developed a close relationship with the latter. While in detention, Esau Oriedo endured torture and the harshest conditions chastened by the British colonial government in Kenya, under the so-called emergency rule; he was denied legal representation and visitation by his family nor associates. Moreover, he bore the arrogation of all his business enterprises, financial, and real-estate property—confiscated as a penal measure by the colonial authorities. Albeit such abominable human rights bête noire sufferance, he never dithered.[13][14] As a freedom fighter, Esau Oriedo advocated for a pan-ethnic African nationalistic independent Kenya; he was at the fore of Kenya’s struggle for her independence from the British colonial rule. His knowledge of the British Judicature of Acts and multiligualism acumen were vital factors for the freedom movement, especially in promoting a pan-ethnic African nationalistic independent Kenya.

Esau Oriedo is accredited among the native Africans who contributed to the growth and headway of the modern Christian church into the interior of the African continent, from 1450 – 1950.[1] He and Chief Otieno wa Andale were principal Africans ascribed with contributing to the successful founding of the Church of God Kima Mission in 1904.He was an ardently effective advocate for the mission by organizing recruitment drives among the native tribes and numerous testimonial appeals to the Church of God’s International Missionary Board headquarters at Anderson in the State of Indiana, United States of America.[4][15] He was one of the first aboriginal Africans to undergo the ordinance of baptism and Communion at the Church of God Kima Mission.

In 1923 he singlehandedly altered the Christian church landscape in Bunyore and the rest of North Nyanza in present day western Kenya; he was an effective crusader against the inimical censorious stance towards the African culture by the colonial Christian church, the Christian missionaries in the Kenya Colony, and the respective overseas mission sponsors. He sought the syncretism of Christianity and African values; a cause that was anathema to the colonial Church of God establishment de jour, which remained decisively and dogmatically intolerant of the native African cultural values. Finding justification lacking in the church's stance, he was forced to forsake the Church of God Kima Mission. And in 1924 he went on to found the St. John's Anglican Church at Ebwali village in Bunyore under the auspices of the Church Mission Society.[1][16] Antecedently, the dominance of the Church of God in Bunyore came to an end in 1924; when Bunyore became the pillar of strength of the Anglican Church.

In the early 1930s Esau Oriedo and Jeremiah Othuoni (1898 – c. 1958) of Enyaita successfully advocated for the chieftainship of Bunyore. Before that, Bunyore was still under the jurisdiction of the Paramount Chief, Nabongo Mumia of Wanga (d. 1949).[6] Mumia had in 1926 been appointed, by the British colonial government, paramount chief of all four traditionally aligned districts of western Kenya; which of course, included the people of Bunyore—Esau Oriedo’s Bantu ethnic Luhya group.[17]

As a trade unionist and a legal advocate and scholar, he was one of the key members of the original trade-union movement in Kenya which advocated for fair wages, suitable employment conditions, and housing for African workers. He made effective use of his knowledge of the British Judicature of Acts to provide legal representation and advocacy to trade unions and its members, and other native African organizations being targeted for persecution by the colonial government as political subversives.[18] His legal acumen, political prescience, and multilingualism made him a valuable resource to the early pan-ethnic and grassroots labor movement in colonial Kenya. The antecedent trade-union movement was impetus to the 1944 formation of the Kenya African Union (KAU) political party which was banned in 1953 during the Mau Mau rebellion;[19] it eventually became Kenya African National Union (KANU)—the party that formed the first African Government of Kenya at independence in 1963.

During the Kakamega Gold Rush of 1930–52[20] he advocated for the unionisation of African mine workers as a non-violent effective approach to fighting for their rights through collective bargaining campaign; he implored the Local Native Council (LNC) of North Nyanza to support the unionisation approach, but was unsuccessful.[6][21][22] Nevertheless, he endeavoured to bring attention and awareness of sympathetic Britons to plight of the native Africans.[23] His efforts and others akin to it were deemed by colonial authorities as antigovernment sedition or rabblerousing and were posthaste outlawed.[24]

He was a member of the multiethnic Kisumu Chamber of Commerce founded in 1927 by the Kavirondo Taxpayers Welfare Association (founded in 1923) under the leadership of Zablon Aduwo Nanyonje; and later in the 1930s was a founding member of North Kavirondo Chamber of Commerce to lobby for the growing number of African retail traders, including himself. Whereas, Kisumu Chamber of Commerce was multiethnic, the Kavirondo Taxpayers Welfare Association became dominated by Luo—Nilotic Kavirondo; hence, the offshoot in 1924 of North Kavirondo Taxpayers Association which drew membership from the Luhya—Bantu Kavirondo. Both Kavirondo and North Kavirondo Taxpayers Associations were initially products of chiefs and their patrons; but, Kisumu Chamber of Commerce and North Kavirondo Chamber of Commerce, respectively, excluded chiefs and their cohorts from membership. The chamber’s mission was to end collision between colonial chiefs and Asian traders, and to oppose the anti-African economic activities regulations by colonial government marketing boards.[13][25][26]

He served as a colonial era district representative in the District House Assembly known as the Local Native Council (LNC) of North Nyanza; one of the 26 countrywide local native legislative units enacted by the colonial government in 1924. In addition to being a district representative, he also served as the council’s chairperson. Notably, the Local Native Council of North Nyanza had the largest colonial era budget of any of the 26 native legislative units in the British Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. (Revenue, 1949) Whereas, the initial intent of enacting Local Native Councils—by the colonial government—was not empowerment self-determination; however, by 1932 during Esau Oriedo’s tenure, the Local Native Council of North Nyanza was making important decisions to steer her own course of action towards establishing important infrastructures to support African. For instance, establishing secular higher education facilities (Mukudi, 1989), agricultural transformation in North Nyanza, free commerce and economic system, healthcare systems, roads, an inclusive sociopolitical process, etc.; the archetype of the North Nyanza LNC secular education initiative is the Government African School Kakamega, present day Kakamega High School.[27] Esau Oriedo, the philanthropist and a literacy advocate, awarded bursaries to individuals from poor families who could not afford to pay fees to attend school. Albeit not focused on steering the recipients towards secular in lieu mission schools; nevertheless, he encouraged the recipients of his bursaries to attend the LNC secular schools. Likewise, the North Nyanza LNC had its own scholarship program which he helped champion. The scholarship was mostly focused on higher education opportunities for talented students who could not afford to attend colleges such as Makerere Medical School at Mengo, in present day Uganda. The archetypical recipient of the North Nyanza LNC scholarships was Arthur Okwemba a cerebrally brilliant young man who went study medicine at Makerere Medical School; Mr. Okwemba personified the 15 percent of Makerere’ students who came from entirely illiterate and humble origins. Individuals such as Arthur Okwemba are an exemplification of Esau Oriedo’s pioneering role in making both early and higher educational opportunity universally accessible for all students without regard to their origin or family societal status.

When Kenya acquired her independence in December 1963, he was elected to multiple terms as a councilman in the County Council of Kakamega; he voluntarily stepped down from the council to pave way for the younger generation, whom he continued to coach and mentor. In 1964 he successfully spearheaded the election to the national parliament of Edward Eric Khasakhala, the first member of parliament (MP) in Bunyore.[10][28]

Biography

Esau Khamati Oriedo born circa 1888 at Ebwali village, North Kavirondo, in the colonial African territory governed by Imperial British East Africa Company, which is now in Kenya. He lost his father early in life and had to craft his way through life as an orphan to become a self-made man who was respected by his peers and revered by his country.

Esau Oriedo grew up an orphan who became self-educated and multilingual—a self-made consummate man who was respected by his peers and revered by his country. He exemplified himself in multi-faceted ways of life by effectively championing a multiplicity of diverse causes. This aspect is contextualized by the myriad of aforesaid contributions. He tirelessly put himself at the fore of the struggle to enhance socioeconomic; sociocultural; political; educational; legal system; and civil infrastructure wherewithal of his native Kenyan homeland.

He championed many human causes—interdisciplinary (socioeconomic & geopolitical) and across ethnicities in his native Kenya.

Politics

As a politician, he was a pragmatic and effective colonial era and early post-colonial era politician. He served as a colonial era district representative in the District House Assembly known as the Local Native Council (LNC) of North Nyanza;[2][29] one of the 26 countrywide local native legislative units enacted by the colonial government in 1924.[30] In addition to being a district representative, he also served as the council’s chairperson. Notably, the Local Native Council of North Nyanza had the largest colonial era budget of any of the 26 native legislative units in the British Colony and Protectorate of Kenya.[31]

He was a member of the Kenya African Union (KAU), a grassroots organiser and an events coordinator, recruited merchants and workers into the organisation.[Note 1]

When Kenya acquired her independence in December 1963, he was elected to several terms as a councilman in the County Council of Kakamega;[3][9] he voluntarily gave up his position—as a councillor—to the younger generation, whom he continued to mentor.

Faith

As a Christian crusader, a champion of religious (Christianity) tolerance and cultural inclusiveness, he challenged the colonial-era Christian church and missionaries in Kenya to embrace the traditional African heritage;[32] he is credited among those Africans whose efforts effectuated successful amelioration and headway of the modern Christian church into Africa’s interior, between 1450 — 1950;[1] in 1923 he spearheaded the founding of St. John’s Anglican Church at Ebwali village in Bunyore, Kenya[16] to counter Church of God’s dominance in Bunyore, after he forsook Church of God Anderson, Indiana, USA Kima Mission[4] in 1923 because of its censoriously inimical stance towards the African culture—until then, he and Chief Otieno wa Ndale were key Africans in the establishment and growth of the Kima Mission; he had been a crucial African member and a principal stakeholder of the Kima mission.[1][15] In 1954 he and his wife were presented with an ex post facto award for their outstanding contribution to the success of the Church of God, Kima mission; the award was conferred by the Kima Mission with the approval of International Missionary Board of Church of God at Anderson, Indiana in the USA.

In 1923 Esau Oriedo singlehandedly altered the Christian church landscape in Bunyore and the rest of North Nyanza. He was a devout Christian, albeit an ardent opponent of the antagonistic stance of the colonial Christian church missionaries and their overseas benefactors toward his native African culture. An embodiment of his embrace of this duality — i.e., a seamless integration of Christianity with the aboriginal African ethos — is contextualized by the events of his wedding in 1923 which blended a Christian holy sacrament of matrimonial covenant which was celebrated at the Church of God, Kima Mission with a traditional African marriage reception which took place at Ebwali village.The wedding reception triggered unmitigated controversy and condemnation from the Reverend H. C. Kramer — the head missionary at the Kima Mission who was the matrimonial service officiant — and the mission's home office in United States of America, Anderson, Indiana. Both Reverend Kramer and the mission's home office denounced the reception as sacrilegious, and demanded an act of contrition by the couple. A disappointed Esau Khamati, the "inquisitor" and advocate of religious inclusiveness, regarded the demands for contrition as an act of religious servitude aimed at his African heritage; the very same heritage, he opined, that had been instrumental in the success of the Church of God mission in the region. He emphatically asserted that he and his wife were pious Christians, created by God in His own image of the familial African birthright; antecedently, he explicated that seeking contrition would be an act of sacrilege. Rather than acquiesce, the newlywed couple challenged fellow African parishioners to embrace their heritage by abdicating the Church of God and founding their own church. In 1923 they founded the Ebwali St. John Anglican Church parish with the full blessings of the British Anglican Archdeacon Walter Edwin Owen; the Archdeacon Owen presided over the archdioceses of the Kavirondo region of the Kenya Colony and the British East African Protectorate of Uganda. The founding of the Ebwali Anglican Church parish by Esau Khamati became the impetus of the evolution of the three-modern era Maseno Dioceses of the Anglican Church of Kenya. Moreover, Esau Khamati not only forsook the Church of God, but he became an impassioned and effective crusader of the Christian Missionary Society. Consequently, in 1924 the dominance of the Church of God in Bunyore came to an end in 1924, when the region became the pillar of strength of the Anglican Church. In 1954 Rev. Daudi Otieno of the Church of God Kima Mission and the Anderson, Indiana mission head office retrospectively venerated Mr. & Mrs. Esau Khamati Oriedo for their illustrious contribution to the Church of God Mission, Kima Bunyore Mission and their continued proselytizing of Christianity in Bunyore and the rest of Nyanza province. Moreover, the Church of God, Anderson, Indiana and the Kima Mission officially acknowledged and registered the 1923 Esau Khamati Oriedo Christian marriage. This ex post facto acknowledgement, of Mr. and Mrs. Esau Khamati Oriedo's matrimony and stewardship to the church and Christianity, ushered in the beginning of a metamorphosis of the Church of God Mission' embrace of a more open attitude towards syncretism of the Christian doctrine with customary indigenous African values; thus, facilitating the effectiveness of the church's teachings.[1][15][33][34]

Activism

As a political activist and freedom fighter, in 1953 he was detained for four years—alongside Chief Koinange Wa Mbiyu (d. 1960), a number of Kenyan founding fathers, and other key Kenyan figures.[5] While in detention, he endured torture and harsh conditions by the British colonial government in Kenya, under the emergency rule; he lost all his business enterprises and property, as a consequence.

As a trade unionist, a legal advocate and scholar, he was one of the key members of the original trade-union movement in Kenya which advocated for fair wages, suitable employment conditions, and housing for African workers.[35]

The Kakamega Gold Rush of 1930-52

As a member of the North Nyanza LNC, and during his tenure as the body's chairman, he joined with other Luhya (Kavirondo-Bantu) leaders and activists to advocate for the Luhya (Kavirondo-Bantu) land rights; especially, during the Kakamega Gold Rush of 1930-52.[20][22][36] Together with the majority of North Nyanza LNC members, asserted that the North Nyanza LNC possessed the statutory rights to all gold revenues; furthermore, they reasoned, the native people of North Kavirondo district of Nyanza Province held absolute ownership of the land (with gold or without gold). Whereas, they maintained, the North Nyanza LNC was the primary body—under the Native Authority Amendment Ordinance, No. 14 of 1924[37][38][39]—with decision-making statutory powers on land already declared as native land, under the colonial and imperial authorities’ strategy of restricting native populations to reservations that were thought to be worthless to colonial and imperial interests. Owing to Archdeacon Owen—he and his colleagues—protested the alienation by colonial and imperial authorities of land owned by the native people of Luhya (North Kavirondo) since the changing of fortunes—gold deposits.[25][26][29] The Native Land Trust Amendment Ordinance of 1932 had once more, anew, denied the native people of Luhya (North Kavirondo) their alienable rights to their land, and the nullification of the already categorically inadequate statutory powers provided to them by the colonial and imperial authority in the form of the North Nyanza LNC established under the Native Authority Amendment Ordinance, No. 14 of 1924.[23]

He also advocated for the African mine workers’ rights; he was an outspoken North Nyanza LNC member on the repugnant working conditions and exiguous rate of pay which the native African gold mine workers were subjected to, in addition to the unmitigated loss of reservation land—assumed worthless by the colonial and imperial authorities of the British Colony and Protectorate of Kenya—allotted them under the Native Land Trust Ordinance of 1924. He urged the North Nyanza LNC to support the unionization of African mine workers as a non-violent effective approach to fighting for their rights through collective bargaining. He endeavored to bring attention and awareness of sympathetic Britons to plight of the native Africans; the plight brought about by the Kakamega Gold Rush of 1930-52. His efforts faced insurmountable peril as the colonial and imperial authorities colluded with European miners, mining companies, and speculators in establishing statutory basis for maintaining bounteous mining workforce at exiguous rate of pay and abhorrent working conditions; consequently, Esau Oriedo’s efforts were deemed by authorities as antigovernment sedition or rabble-rousing.

In 1964 he founded of Kenya Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Bunyore Branch (registered on 3 June 1964).;[12] a not-for-profit, non-governmental, member based organization chartered with promoting conducive and productive business environment, regulatory advocacy, community stewardship, literate local human resources, raw material and technology, and a creation of commerce and industry infrastructure able to attract sustainable business development to further socioeconomic welfare of all communities in Bunyore.

The Bunyore Chieftaincy

Esau Oriedo and Jeremiah Othuoni were political frontier activist whose gallantry and altruism through political defiance effectuated progressive change; change that brought Bunyore chieftaincy structure that was supported by the Nyore/Nyole community. Important to note that pre-European acephalous Nyore/Nyole of Bantu Kavirondo/Luhya, like other Bantu Kavirondo/Luhya, were a sovereign people; (Gutkind) thus, system of rule by the British colonial Government Officials supported by appointed chiefs in disregard of the traditional power structures engendered contemptuousness, which Kenyatta charismatically delineated among the Bantu Gikuyu people of central Kenya, and that which Esau Oriedo and Jeremiah Othuoni reproachfully resisted.

Colonial-era court clerk and interpreter

He was multi-lingual, capable of speaking and writing in several languages; because of this talent he was chosen by the British judiciary to become a court interpreter and clerk through which he acquired considerable knowledge and skills in the British legal system. During the struggle for Kenya’s independence he used his knowledge of the British law to advocate for the rights of the Africans; he provided free legal representation to Africans charged with political crimes by the British colonial government in Kenya under the state of emergency rule and the general provisions of seditious speeches and acts.[7]

Entrepreneur

He was an entrepreneur, a merchant and commercial miller with business enterprises across the country, in 1938 he became the first African to own and operate, in absolute, an automated commercial scale Posho/Grain Mill—for gristing and grinding maize and other genera of comestible grain—in North and South Nyanza regions in present-day Western and Nyanza provinces in the east African Republic of Kenya.

In the 1920s he established Oriedo, Esau & Sons trading company which later became a national enterprise with branches in all major cities of the British Kenyan colony and independent Republic of Kenya. He established an effective supply chain and brokerage infrastructure for the business, and was recognised accordingly in a report commissioned by US Agency for International Development on agro-industrial enterprises in Kenya.[8][11]

As a businessman he developed close and effective business partnerships and social friendships with the Kenyan Indian/Asian communities, including speaking Hindi with adequate reading & writing skills. Indian merchants were prominent in economic development in colonial and postcolonial east Africa.

Philanthropy

Esau Oriedo was a philanthropist who supported multifaceted human causes—in 1923 he spearheaded the founding of Ebwali St. John’s Anglican at Bunyore, Kakamega District (presently, Vihiga district) in Kenya; he ceded funds and property to the church and Ebwali Primary School, provided bursaries and other kinds of financial support to help promote the welfare of those in need. In 1964 he founded “Oriedo Self Help Society” (registered on 3 June 1964);[12] a non-governmental charitable foundation whose primary objective was to further socioeconomic welfare of communities in Bunyore and beyond, via self-driven and outcome-based sustainable development initiatives aimed at establishing socioeconomic self-sufficiency in the region.

He was an advocate and promoter of literacy and higher education, which became his lifelong pursuit—as District Representative in Native Local Council of North Nyanza he spearheaded the creation of a secular schooling system to rival mission schools.[20]

Soldier

He was a veteran of World War I and World War II, a frontline foot soldier in the British Army's King's African Rifles (KAR) regiment, stationed in Burma during the second world war.[40]

Timeline of key event in his life

| CATEGORY | EVENT |

|---|---|

| Freedom Fighter & Advocate for the Rights of Native Peoples |

|

| Politician |

|

| Trade Unionist | He was one of the key members of the original trade-union movement in Kenya which advocated for fair wages; employment conditions and housing for African workers. Trade-union movement was the catalytic impetus of the political movement; the Kenya African Union which later became Kenyan African National Union (KANU) is a direct descendant of trade-union movement in Kenya.

He advocated for the unionisation of African mine workers as a non-violent effective approach to fighting for their rights through collective bargaining campaign, and implored the North Nyanza LNC to support the unionisation approach, but was unsuccessful. Nevertheless, endeavoured to bring attention and awareness of sympathetic Britons to plight of the native Africans; the plight brought about by the Kakamega Gold Rush of 1930–52. His efforts and others akin to it were deemed by colonial authorities as antigovernment sedition or rabblerousing and were posthaste outlawed.[24]

|

| Philanthropist | Led by example and was an inspirational role model to many Kenyans across ethnicities, geopolitical and economic spectra; he provided many, and of course his siblings, with formal educational opportunities to attain their highest possible potential.[49][Note 6]

He gave property to his kinfolks, donated funds to business enterprises, to church organisations and to charity. He ensured that his relatives as well as his friends received education to literate and numerate, and achieved apprentice skills.

|

| Soldier | He was a veteran of the First and the Second World Wars as a soldier in the King's African Rifle (KAR)

|

| Religious Scholar and Activist | He was fascinated with theological comparative grasp of the similarities and contrasts between Christianity and traditional African heritage, and religious practices of other cultures; a quest that led to his exhaustive study of the bible and other related literary works.

|

| Entrepreneur | He was a successful entrepreneur—a merchant and commercial miller with business enterprises across the country—North Nyanza, South Nyanza, and Central Provinces (Western, Nyanza, & Central provinces of Republic of Kenya; colonial era British Colony and Protectorate of Kenya).

Founded Oriedo, Esau & Sons trading company with multiply diverse business units. He established one of the most effective business supply chain and brokerage infrastructure.[11] As a businessman he developed close and effective business partnerships and social friendships with the Kenyan Indian/Asian communities, including speaking Hindi with adequate reading & writing skills. Worthwhile to note that Indian merchants contributed immensely to economic development in colonial and postcolonial east Africa, albeit monopolising trade in the region.[51][52]

|

| Legal Advocate | He made effective use of his knowledge of British Judicature of Acts to provide legal representation and advocacy to trade unions and its members, and other native African organisations being targeted for persecution by the colonial government as political subversives.

|

Notes

- ↑ The KAU was founded in 1944 and was chartered with fighting for Kenya's autonomy via peaceable but stolid rebellion against colonial rule. The KAU was an offspring of the trade union movement in Kenya and a forerunner to the Kenya African National Union (KANU). Despite the organization's proscription in 1952 by the British colonial government, former KAU members and leaders led successful peaceful negotiations which resulted in Kenya's independence.

- ↑ A battle-hardened soldier and a student of the British military strategies, he developed a profound appreciation for and understanding of nationhood—organizing the different native African population in the British Colony and Protectorate of Kenya into a single nation by aggregating and embracing her diverse ethnicities; he saw how soldiers from different races and ethnicities, and units fighting under the British banner were effectively leveraged in successfully attaining common military interests. The enlightenment lay bare to him that European culture as embodied in their military strategies was akin to his own traditional African culture of communalism teamwork to attain a common purpose. He espoused the amalgamation of the native African cause(s) and nationalism, cognizing that these constituents were indissoluble—you could not advocate for one without the other.

- ↑ This was in consequence to which, not only, was the colonial system of reservations troublesome to the Bantu Kavirondo people, but then again, to implement the flawed recommendations contained in the report by Committee on Native Land Tenure in North Kavirondo Reserve—which included fiscal policy provisions that mandated land registration and corresponding registration fees and other forms of levies—was futile; the Bantu Kavirondo people viewed such stipulation as a tyrannical subjugation whose implication(s) inferred that their land—the land of their forefathers—was being claimed by the imperial and colonial authorities and their native cronies. An act which hoisted the imperial and colonial authorities and their native cronies to landlords; whereas, consigning the native Africans of North Kavirondo to a class of squatter or tenant denizens on their own lands, a feat that tradition obliged be met with perspicuous contemptuous resistance.

- ↑ Whereas, the initial intent of enacting Local Native Councils—by the colonial government—was not empowerment self-determination; however, by 1930s the Local Native Council of North Nyanza was making important decisions to steer her own course of action towards establishing important infrastructures to support African. For instance, establishing secular higher education facilities, agricultural transformation in North Nyanza, free commerce and economic system, healthcare systems, roads, an inclusive sociopolitical process, etc.

- ↑ He served multiple terms as a councilor—an elected member of Kakamega County Council; County Councils were local political governing federations of the newly restructured country, the Republic of Kenya.

- ↑ His younger brother, Bernard W. A. Oriedo (d. 20 January 1983), was such benefactor—of his academic bursaries and purposeful championing of formal education in colonial era Kenya—who took full advantage of the opportunity, gifted him by his elder brother, to attain his highest possible potential and became a very accomplished pharmacist. Also, Bernard was amongst a handful of native Kenyans of his generation (in the second decade of the 20th century) to be awarded an equivalent of today’s college diploma, in healthcare profession; three years after independence, Bernard was appointed to a nationwide post of Children’s Officer—one of the highest levels of civil service at the time—by former President Daniel T. Arap Moi, who was then the Minister for Home Affairs.

- ↑ An embodiment of his embrace of this duality is his own wedding in 1923 which blended a Christian service at Kima mission with a traditional African reception at Ebwali village. The church wedding was presided over by H. C. Kramer the head of Church of God Anderson, Indiana Kima Mission at Kima in present-day Bunyore, Kenya which—to the chagrin of Church of God missionary. The original Church of God Mission, Kima Bunyore Mission "Certificate of Marriage" issued ex post facto to Mr. and Mrs. Esau Khamati Oriedo on 12 November 1954 (signed by Rev. Daudi Otieno); in recognition of Mr. & Mrs. Oriedo's previous contribution to the Church of God Mission, Kima Bunyore Mission and their continued proselytizing of Christianity in Bunyore and the rest of Nyanza province. This ex post facto acknowledgement, of Mr. and Mrs. Esau Khamati Oriedo's matrimony and stewardship to the church and Christianity, ushered in the beginning of a metamorphosis of the Church of God Mission' embrace of a more open attitude towards syncretism of the Christian doctrine with customary indigenous African values, which facilitated the effectiveness of the church's teachings.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hastings, Adrian. The Church in Africa, 1450–1950. London: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- 1 2 British Colonial Office of The Government of Great Britain, The Crown. Colonial Reports—Annual Report on the Social and Economic Progress of the People of the Kenya Colony And Protectorate, 1931. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1931.

- 1 2 The Government of Kenya. "Kakamega County Council Elected Members." Kanya Gazette. Vol. 68. 6. Nairobi: Official Publication of the Government of the Republic of Kenya, 8 February 1966.

- 1 2 3 4 Kima Church of God Mission. "Church Archival Records." Kima, Bunyore, ca. 1915 – 1985.

- 1 2 3 Great Britain. East Africa Royal Commission, Great Britain. Parliament, Great Britain. Colonial Office. East Africa Royal Commission 1953–1955 report. Great Britain: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1955.

- 1 2 3 Solomon, Alan C. and Lohrentz, Kenneth P., "Guide to Nyanza Province Microfilm Collection, Kenya National Archives, Part III: Section 10, Daily Correspondence and Reports, 1930–1963, Vol. II" (1975). Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs – Former Departments, Centers, Institutes and Projects. Paper 1.

- 1 2 Benjamin N. Lawrance, Emily Lynn Osborn, and Richard L. Roberts. "Intermediaries, Interpreters, and Clerks: African Employees in the Making of Colonial Africa." Benjamin N. Lawrance, Emily Lynn Osborn, and Richard L. Roberts. Intermediaries, Interpreters, and Clerks: African Employees in the Making of Colonial Africa. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2006. 189.

- 1 2 United States Agency for International Aid (USAID). pdf documents: PNAAM016.pdf. 1 July 2013. <http://www.usaid.gov>.

- 1 2 The Republic of Kenya. "Kakamega County Council Elections." The Kenyan Gazette (1966): 151.

- 1 2 3 "Emuhaya constituency". www.emuhaya.co.ke. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- 1 2 3 Devres, Inc. Technology and Management Needs of Small and Medium Agro-Industrial and Enterprises in Kenya: Implication for An International Agro-Industrial Service Center. United States Government. Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for International Development (U.S.A.I.D.), 1981.

- 1 2 3 4 R. D. McLaren, Assistant Registrar of Societies, Government of Kenya. "Notice of Registered Societies." Kenya Gazette. Nairobi: Official Publication of the Government of the Republic of Kenya, 13 March 1964.

- 1 2 Lonsdale, John. Mau Mau & nationhood: arms, authority & narration. Ohio State University Press, 2003.

- ↑ Elkins, Caroline. Imperial reckoning: The untold story of Britain's gulag in Kenya. Macmillan, 2005.

- 1 2 3 Anderson University and Church of God. "Church of God (Anderson, Ind.) Missionary Board. Missionary Board correspondence. [ca. 1915]-1985." Anderson University and Church of God Archives. Anderson: Anderson University and Church of God Archives, 1994.

- 1 2 The Anglican Church of Kenya. About Anglican Church of Kenya: Church History.

- ↑ Greenberg, J. H. (1950), The Bantu of North Kavirondo. Volume I. Günter Wagner. American Anthropologist, 52: 255–256. doi: 10.1525/aa.1950.52.2.02a00190

- ↑ Singh, Makhan. History of Kenya's trade union movement, to 1952. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1969.

- 1 2 Lonsdale, John. Journal of African Cultural Studies:KAU's Cultures: Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after the Second World War. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, LTD., 2000.

- 1 2 3 Mukudi, Edith Sumba Wanyama. Thesis (M.Ed) – Kenyatta university: African contribution to the growth of secular education in North Nyanza, 1920–1945. Nairobi: Kenyatta university, 1989.

- ↑ Solomon, Alan C., "Guide to Nyanza Province Microfilm Collection, Kenya National Archives, Part II: Section 10A, Correspondence and Reports, 1899–1942" (1974). Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs – Former Departments, Centers, Institutes and Projects. Paper 3.

- 1 2 Solomon, Alan C. and Crosby, C. A., "Guide to Nyanza Province Microfilm Collection, Kenya National Archives, Part I: Section 10B,Correspondence and Reports 1925–1960" (1974). Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs – Former Departments, Centers,Institutes and Projects. Paper 4.

- 1 2 Kenya. Committee on Native Land Tenure in the North Kavirondo Reserve. Committee on Native Land Tenure in the North Kavirondo Reserve. Socioeconomic & Political History. Nairobi: Printed by the Government Printer, 1932.

- 1 2 Anderson, David M. "Master and Servant in Colonial Kenya." The Journal of African History 41.3 (2000): 459–485.

- 1 2 Murray, Nancy Uhlar. "Archdeacon WE Owen: Missionary as Propagandist." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 15.4 (1982): 653-670.

- 1 2 Charles G. Richards, Archdeacon Owen of Kavirondo: A Memoir (1947)

- ↑ Schilling, Donald G. "Local native councils and the politics of education in Kenya, 1925-1939." The International Journal of African Historical Studies9.2 (1976): 218-247.

- ↑ Hornsby, Charles. Kenya: A history since independence. IB Tauris, 2013.

- 1 2 Colonial Reports: The Official Gazette of The Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 10 June 1925.

- ↑ The Resident Natives Ordinance, Ord 19 of 1924. Kenya Gazette, 16 October 1924.

- ↑ Revenue, O. "African Affairs." Oxford Journals (1949): 311–317

- ↑ Spencer, Leon P. "Christianity and Colonial Protest: Perceptions of W. E. Owen, Archdeacon of Kavirondo." Journal of Religion in Africa 13.1 (1982): 47–60. Electronic/Internet. 11 August 2013. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1581117>.

- ↑ Hastings, Adrian (1995). The Church in Africa, 1450–1950. London: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ The original Church of God Mission, Kima Bunyore Mission “Certificate of Marriage” issued ex post facto to Mr. and Mrs. Esau Khamati Oriedo on 12 November 1954 (signed by Rev. Daudi Otieno), in recognition of Mr. & Mrs. Oriedo’s previous contribution to the Church of God Mission, Kima Bunyore Mission and their continued proselytizing of Christianity in Bunyore and the rest of Nyanza province.

- ↑ Singh, Makhan. History of Kenya's trade union movement, to 1952. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1969.

- ↑ MacArthur, Julie. Cartography and the Political Imagination: Mapping Community in Colonial Kenya. Ohio University Press, 2016.

- ↑ McGregor, Ross W. Kenya from Within: A Short Political History. Routledge, 2012.

- ↑ H. C. Willan, H. G. Morgan, Rupert Haig, G. W. McL. Henderson, M. Ralph Hone, A. Hallam Roberts and Cecil H. A. Bennett, East Africa", Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law Vol. 21, No. 3 (1939), pp. 149-158

- ↑ "East Africa on JSTOR" (PDF). www.jstor.org. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ↑ Brands, Hal. "Wartime Recruiting Practices, Martial Identity and Post-world War II Demobilization in Colonial Kenya." Journal of African History 46.1 (2005): 103–125.

- ↑ "East Africa Royal Commission 1953–1955 report." Great Britain. East Africa Royal Commission, Great Britain. Parliament, Great Britain. Colonial Office. Printed by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1955.

- ↑ Anthony Clayton, Donald Cockfield Savage. Government and Labour in Kenya 1895–1963. Routledge: Frank Cass and Company LTD, 1974.

- 1 2 KENYA. Committee on Native Land Tenure in the North Kavirondo Reserve. Committee on Native Land Tenure in the North Kavirondo Reserve. Socioeconomic & Political History. Nairobi: Printed by the Government Printer, 1932.

- 1 2 Owen, W.E. "The Bantu of Kavirondo." 1932.

- ↑ The National Archives-United Kingdom. The Kenya Land Commission Report. Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Colonies. His Britannic Majesty's Government (United Kingdom). London: His Britannic Majesty's Government (United Kingdom), 1934. Electronic. 15 August 2013.

- 1 2 E. S. Atieno Odhiambo, John Lonsdale. Mau Mau & Nationhood: Arms, Authority & Narration. Ohio State University Press, 2003.

- ↑ Lonsdale, J. (2000). Journal of African Cultural Studies: KAU's Cultures: Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after the Second World War. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

- ↑ Anthony Clayton, Donald Cockfield Savage. Government and Labour in Kenya 1895–1963. Routledge: Frank Cass and Company LTD, 1974

- ↑ Republic of Kenya. "Appointments by D. T. Arap Moi, Minister for Home Affairs: Children's Officers, Ministry of Home Affairs." The Kenya Gazette. Nairobi: The Government of The Republic of Kenya, 15 February 1966.

- ↑ R. D. McLaren, A. R. (13 March 1964). Notice of Registered Societies. Kenya Gazette. Nairobi, Kenya: Official Publication of the Government of the Republic of Kenya

- ↑ David Himbara, “Kenyan Capitalists, the State, and Development: Businessmen” (East African Publishers, 1994).

- ↑ J. S. Mangat, “A History of the Asians in East Africa—c. 1886–1945” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969)

- ↑ Devres, Inc. (1981). “Technology and Management Needs of Small and Medium Agro-Industrial and Enterprises in Kenya: Implication for An International Agro-Industrial Service Center.” United States Government, Development Support Bureau. Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for International Development (U.S.A.I.D.).

- ↑ Benjamin N. Lawrance, Emily Lynn Osborn, and Richard L. Roberts. "Intermediaries, Interpreters, and Clerks: African Employees in the Making of Colonial Africa." Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2006.