Employment authorization document

An employment authorization document (EAD, Form I-765) or EAD card, known popularly as a "work permit", is a document issued by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) that provides temporary employment authorization to noncitizens in the United States.

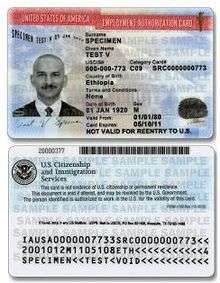

Currently the EAD is issued in the form of a standard credit card-size plastic card enhanced with multiple security features. The card contains some basic information about the alien: name, birth date, sex, immigrant category, country of birth, photo, alien registration number (also called "A-number"), card number, restrictive terms and conditions, and dates of validity. This document, however, should not be confused with the green card.

Obtaining an EAD

To request an EAD card, noncitizens who qualify may file Form I-765, "application for employment authorization." Applicants must then send the form via mail to the USCIS Regional Service Center that serves their area. They may also be eligible to file Form I-765 electronically (see USCIS Electronic Filing). If approved, an EAD will be issued for a specific period of time based on alien's immigration situation.

Thereafter, USCIS will issue EADs in the following categories:

- Renewal EAD: Renewal cannot be filed more than 120 days before the current employment authorization expires.[1]

- Replacement EAD: Replaces a lost, stolen, or mutilated EAD. A replacement EAD also replaces an EAD that was issued with incorrect information, such as a misspelled name.[1]

For employment based green card applicants, your priority date needs to be current to apply for Adjustment of Status (I-485) at which time you can apply for EAD. Typically, it is recommended to apply for Advance Parole (AP) at the same time so that you do not have to get a visa stamping when re-entering US from a foreign country.

Interim EAD

An interim EAD is an EAD issued to an eligible applicant when USCIS has failed to adjudicate an application within 90 days of receipt of a properly filed EAD application or within 30 days of a properly filed initial EAD application based on an asylum application filed on or after January 4, 1995.[1] The interim EAD will be granted for a period not to exceed 240 days and is subject to the conditions noted on the document.

An interim EAD is no longer issued by local service centers. One can however take an INFOPASS appointment and place a service request at local centers, explicitly asking for it if the application exceeds 90 days and 30 days for asylum applicants without an adjudication.

Restrictions

The eligibility criteria for employment authorization is detailed in the Federal Regulations section 8 C.F.R. §274a.12.[2] Only aliens who fall under the enumerated categories are eligible for an employment authorization document. Currently, there are more than 40 types of immigration status that make their holders eligible to apply for an EAD card.[3] Some are nationality-based and apply to a very small number of people. Others are much broader, such as those covering the spouses of E-1, E-2, E-3 or L-1 visa holders.

Qualifying EAD categories

The category includes the persons who either are given EAD incident to their status or must apply for EAD in order to accept the employment.[1]

- Asylee/Refugee, their spouses, and their children

- Citizens or nationals of countries fallen in certain categories

- Foreign students with active

- F-1 status who wish to pursue

- Pre- or Post-Optional Practical Training, either paid or unpaid, which must be directly related to the students' major of study

- Optional Practical Training for designated science, technology, engineering, and mathematics degree holders, where the beneficiary must be employed for paid positions directly related to the beneficiary's major of study, and the employer must be using E-Verify

- The internship, either paid or unpaid, with authorized International Organization

- The off-campus employment during the students' academic progress due to significant economic hardship, regardless of the students' major of study

- M-1 status who wish to pursue practical training which is directly related to the students' vocational training from the school

- F-1 status who wish to pursue

- Spouses of exchange visitors with certain regulation

- Eligible dependents of employees of diplomatic missions, International Organization, or NATO

- Certain employment-based nonimmigrants; limits may apply

- Certain family-Based nonimmigrants

- Persons within the adjustment-of-status categories

- Other eligible categories

Persons who do not qualify for EAD

The following persons do not qualify for EAD nor can they accept any employment in the United States, unless the incident of status may allow.

- Visa waived persons for pleasure

- B-2 visitors for pleasure

- Transferring passengers via U.S. port-of-entry

The following persons do not qualify for EAD, even if they are authorized to work in certain conditions, according to the US Citizenship and Immigration Service regulations (8 CFR Part 274a).[4] Some statuses may be authorized to work only for a certain employer, under the term of 'alien authorized to work for the specific employer incident to the status', usually who has petitioned or sponsored the persons' employment. In this case, unless otherwise stated by DHS, no approval from either DHS or USCIS is needed.

- Temporary non-immigrant workers employed by sponsoring organizations holding following status:

- H

- I

- L-1

- O-1

- Foreign student holding F-1 nonimmigrant student status, with certain working hour limitations, who is pursuing:

- on-campus employment, regardless of the students' field of study

- curricular practical training for paid (can be unpaid) alternative study, pre-approved by the school, which must be the integral part of the students' study

- Exchange visitor employed by sponsoring organizations; limits may apply

- Crew members, only for the carrier who has employed the persons

Background: immigration control and employment regulations

Undocumented immigrants have been considered a source of low-wage labor, both in the formal and informal sectors of the economy. However, in the late 1980s with an increasing influx of un-regulated immigration, many worried about how this would impact the economy and, at the same time, citizens. Consequently, in 1986 congress enacted the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) “in order to control and deter illegal immigration to the United States” resulting increasing patrolling of U.S. borders.[5] Additionally, IRCA, implemented new employment regulations that imposed employer sanctions, criminal and civil penalties "against employers who knowingly [hired] illegal workers.” [6] Prior to this reform, employers did not have to worry about the legal status of employees, thus for the very first time, this reform "made it a crime for undocumented immigrants to work" in the United States.[7] Raising the topic of employment illegality for undocumented immigrants.

Additionally, thereafter, the “Employment Eligibility Verification" document or I-9 form, was then used by employers to “verify the identity and employment authorization of individuals hired for employment in the United States." [8] While this form is not to be submitted unless requested by government officials, it is required that all employers have an I-9 form from each of their employees, which they must be retain for three years after day of hire or one year after employment is terminated.[9]

I-9 qualifying citizenship or immigration statuses

- A citizen of the United States

- A noncitizen national of the United States

- A lawful permanent resident

- An alien authorized to work

- As an "Alien Authorized to Work," the employee must provide an "A-Number" present in the EAD card, along with the expiration day of the temporary employment authorization. Thus, as established by form I-9, the EAD card is a document which serves as both an identification and verification of employment eligibility.[8]

Conccurrently, the Immigration Act of 1990 “increased the limits on lawful immigration to the United States," [...] "established new nonimmigrant admission categories," and revised acceptable grounds for deportation. Most importantly, it brought to light the "authorized temporary protected status" for aliens of designated countries.[5]

Through the revision and creation of new classes of nonimmigrants, qualified for admission and temporary working status, both IRCA and the Immigration Act of 1990 provided legislation for the regulation of employment of noncitizen.

The 9/11 attacks brought to the surface the weak aspect of the immigration system. After 9/11, the United States intensified its focus on interior reinforcement of immigration laws to reduce "illegal immigration" and to identify and remove criminal aliens in effort to prevent another terrorist attack.[10]

Temporary worker: Alien Authorized to Work

Undocumented Immigrants, are individuals in the United States without lawful status. When this individuals qualify for some form of relief from deportation, individuals may qualify for some form of legal status. In this case, temporarily protected noncitizens are those who are granted "the right to remain in the country and work during a designated period." Thus, this is kind of an "in-between status" that provides individuals temporary employment and temporary relief from deportation, but it does not lead to permanent residency or citizenship status.[1] Therefore, an EAD should not be confused with a legalization document or be considered synonymously of permanent or citizenship status. The EAD is given, as mentioned before, to eligible noncitizens as part of a reform or law that gives individuals temporary legal status

Temporary legal statuses granted, to otherwise undocumented immigrants, the ability to achieve socioeconomic incorporation by obtaining an EAD and receiving relief from deportation.

Examples of "Temporarily Protected" noncitizens (eligible for EAD)

- Temporary Protected Status (TPS)

- Under TPS, individuals are given relief from deportation as temporary refugees in the United States. Under TPS individuals are given protected status if found that “conditions in that country pose a danger to personal safety due to ongoing armed conflict or an environmental disaster”. This status is granted typically for 6 to 18 month periods, eligible for renewal unless the individual's Temporary Protected Status is terminated by USCIS. If withdrawal of TPS occurs, the individual faces exclusion or deportation proceedings.[11]

- Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA)

- DACA was authorized by President Obama in 2012, it provided qualified undocumented youth "access to relief from deportation, renewable work permits, and temporary Social Security numbers." [12]

- Currently Blocked and Awaiting Implementation

- Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA): Similar to DACA, if enacted, DAPA would provide parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, protection from deportation and make them eligible for an EAD card.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Instructions for I-765, Application for Employment Authorization" (PDF). U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2015-11-04. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "Classes of aliens authorized to accept employment". Government Printing Office. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ↑ "Employment Authorization". USCIS. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "TITLE 8 OF CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS (8 CFR) | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- 1 2 "Definition of Terms | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ Ngaio, Mae M. (2004). Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 266. ISBN 9780691124292.

- ↑ Abrego, Leisy J. (2014). Sacrificing Families: Navigating Laws, Labor, and Love Across Borders. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804790574.

- 1 2 "Employment Eligibility Verification". USCIS. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ Rojas, Alexander G. (2002). "Renewed Focus on the I-9 Employment Verification Program". Employment Relations Today. 29 (2): 9–17. doi:10.1002/ert.10035. ISSN 1520-6459.

- ↑ Mittelstadt, M.; Speaker, B.; Meissner, D. & Chishti, M. (2011). "Through the prism of national security: Major immigration policy and program changes in the decade since 9/11." (PDF). Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "§ Sec. 244.12 Employment authorization. | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ Gonzales, Roberto G.; Veronica Terriquez & Stephen P. Ruszczyk. (2014). "Becoming DACAmented Assessing the Short-Term Benefits of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)." (PDF). American Behavioral Scientist. 58 (14): 1852–1872. doi:10.1177/0002764214550288. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ Capps, R., Koball, H., Bachmeier, J. D., Soto, A. G. R., Zong, J., & Gelatt, J. (2016). "Deferred Action for Unauthorized Immigrant Parents"