Bozeman, Montana

| Bozeman, Montana | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

|

Aerial view of Bozeman | ||

| ||

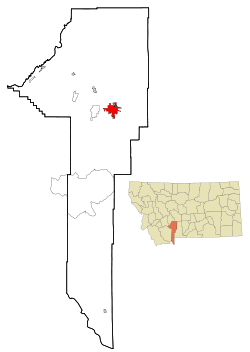

Location of Bozeman, Montana | ||

Bozeman, Montana Location in the United States | ||

| Coordinates: 45°40′40″N 111°2′50″W / 45.67778°N 111.04722°WCoordinates: 45°40′40″N 111°2′50″W / 45.67778°N 111.04722°W[1] | ||

| Country | United States | |

| State | Montana | |

| County | Gallatin | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Carson Taylor | |

| • City Manager | Chris Kukulski | |

| Area[2] | ||

| • City | 19.15 sq mi (49.60 km2) | |

| • Land | 19.12 sq mi (49.52 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) | |

| Elevation | 4,820 ft (1,461 m) | |

| Population (2010)[3] | ||

| • City | 37,280 | |

| • Estimate (2015)[4] | 43,405 | |

| • Density | 1,949.8/sq mi (752.8/km2) | |

| • Metro | 97,308 | |

| • Demonym | Bozemanite | |

| Time zone | MST (UTC-7) | |

| • Summer (DST) | MDT (UTC-6) | |

| ZIP codes | 59715, 59717-59719, 59771-59772 | |

| Area code(s) | 406 | |

| FIPS code | 30-08950 | |

| GNIS feature ID | 0769173 | |

| Website | www.bozeman.net | |

Bozeman is a city in and the county seat of Gallatin County, Montana, United States,[5] in the southwestern part of the state. The 2010 census put Bozeman's population at 37,280 and the 2015 census estimate put the population at 43,405 making it the fourth largest city in the state.[6] It is the principal city of the Bozeman, MT Micropolitan Statistical Area, consisting of all of Gallatin County with a population of 97,304.[7] It is the largest Micropolitan Statistical Area in Montana and is the third largest of all of Montana’s statistical areas.[8][9]

The city is named after John M. Bozeman who established the Bozeman Trail and was a key founder of the town in August 1864. The town became incorporated in April 1883 with a city council form of government and in January 1922 transitioned to its current city manager/city commission form of government. Bozeman was elected an All-America City in 2001 by the National Civic League.[10]

Bozeman is a college town, home to Montana State University.[11] The local newspaper is the Bozeman Daily Chronicle, and the city is served by Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport.

History

Early history

For thousands of years indigenous people of the United States, including the Shoshone, Nez Perce, Blackfeet, Flathead, Crow Nation and Sioux traveled through the area, called the "Valley of the Flowers",[12] although the Gallatin Valley, in which Bozeman is located, was primarily within the territory of the Crow people.

Nineteenth century

William Clark visited the area in July 1806 as he traveled east from Three Forks along the Gallatin River. The party camped 3 miles (4.8 km) east of what is now Bozeman, at the mouth of Kelly Canyon. The journal entries from Clark's party briefly describe the future city's location.[13]

John Bozeman

In 1863 John Bozeman, along with a partner named John Jacobs, opened the Bozeman Trail, a new northern trail off the Oregon Trail leading to the mining town of Virginia City through the Gallatin Valley and the future location of the city of Bozeman.

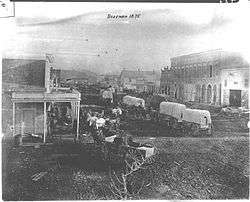

John Bozeman, with Daniel Rouse and William Beall platted the town in August 1864, stating "standing right in the gate of the mountains ready to swallow up all tenderfeet that would reach the territory from the east, with their golden fleeces to be taken care of".[14] Red Cloud's War closed the Bozeman Trail in 1868, but the town's fertile land attracted permanent settlers.

Nelson Story

In 1866 Nelson Story, a successful Virginia City, Montana, gold miner originally from Ohio entered the cattle business. Story braved the hostile Bozeman Trail to successfully drive ~1000 head of longhorn cattle into Paradise Valley just east of Bozeman. Eluding the U.S. Army, who tried to turn Story back to protect the drive from hostile Indians, Story's cattle formed one of the earliest significant herds in Montana's cattle industry.[15] Story established a sizable ranch in the Paradise Valley and holdings in the Gallatin Valley. He later donated land to the state for the establishment of Montana State University – Bozeman.[16]

Fort Ellis

Fort Ellis 45°39′16″N 110°56′35″W / 45.65444°N 110.94306°W, el. 4,987 feet (1,520 m)[17] was established in 1867 by Captain R. S. LaMotte and two companies of the 2nd Cavalry, after the mysterious death of John Bozeman near the mouth of Mission Creek on Yellowstone River 45°42′52″N 110°23′20″W / 45.71444°N 110.38889°W,[18][19] and considerable political disturbance in the area led local settlers and miners to feel a need for added protection. The fort, named for Gettysburg casualty Colonel Augustus Van Horne Ellis, was decommissioned in 1886 and few remnants are left at the actual site, now occupied by the Fort Ellis Experimental Station of Montana State University.[20] In addition to Fort Ellis, a short-lived fort, Fort Elizabeth Meagher (also simply known as Fort Meagher), was established in 1867 by volunteer militiamen. This fort was located eight miles (13 km) east of town on Rocky Creek.45°38′30″N 110°55′05″W / 45.64167°N 110.91806°W, el. 5,249 feet (1,600 m)[21]

Other

The first issue of the weekly Avant Courier newspaper, the precursor of today's Bozeman Chronicle was published in Bozeman on September 13, 1871.[22]

Bozeman's main cemetery, Sunset Hills Cemetery, was gifted to the city in 1872 when the English lawyer and philanthropist William Henry Blackmore purchased the land after his wife Mary Blackmore died of pneumonia in Bozeman in July 1872.[24]

The first library in Bozeman was formed by the Young Men's Library Association in a room above a drugstore in 1872. It later moved to the mayor's office and was taken over by the city in 1890.[24]

The first Grange meeting in Montana Territory was held in Bozeman in 1873.[25] The Northern Pacific Railway reached Bozeman from the east in 1883.[26] By 1900 Bozeman's population reached 3,500.

In 1892 the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries established a fish hatchery on Bridger Creek at the entrance to Bridger Canyon. The fourth oldest fish hatchery in the United States, the facility ceased to be primarily a hatchery in 1966 and became the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Bozeman National Fish Hatchery, later a fish technology and fish health center. The Center receives approximately 5000 visitors a year observing biologists working on diet testing, feed manufacturing technology, fish diseases, brood stock development and improvement of water quality.[27][28]

Montana State University - Bozeman was established in 1893 as the state's land-grant college, then named the Agricultural College of the State of Montana. By the 1920s, the institution was known as Montana State College, and in 1965 it became Montana State University.[29]

Twentieth century

Bozeman's first high school, the Gallatin Valley High School, was built on West Main Street in 1902. Later known as Willson School, named for notable Bozeman architect Fred Fielding Willson, son of Lester S. Willson, the building still stands today and functions as administrative offices for the Bozeman School District.[30]

In the early 20th century, over 17,000 acres (69 km2) of the Gallatin Valley were planted in edible peas harvested for both canning and seed.[31] By the 1920s, canneries in the Bozeman area were major producers of canned peas, and at one point Bozeman produced approximately 75% of all seed peas in the United States.[32] The area was once known as the "Sweet Pea capital of the nation" referencing the prolific edible pea crop. To promote the area and celebrate its prosperity, local business owners began a "Sweet Pea Carnival" that included a parade and queen contest. The annual event lasted from 1906 to 1916. Promoters used the inedible but fragrant and colorful sweet pea flower as an emblem of the celebration. In 1977 the "Sweet Pea" concept was revived as an arts festival rather than a harvest celebration, growing into a three-day event that is one of the largest festivals in Montana.[31]

The first federal building and Post Office was built in 1915. Many years later, while empty, it was a film location, along with downtown Bozeman, in A River Runs Through It (1992) by Robert Redford, starring Brad Pitt. It is now used by HRDC, a community organization.

The Bridger Bowl Ski Area45°49′02″N 110°53′48″W / 45.81722°N 110.89667°W[33] operates as a 501(c)(4) organization by the Bridger Bowl Association, and is located on the northeast face of the Bridger Mountains, utilizing state and federal land.[34] Bridger Bowl was Bozeman's first ski area and opened to the public in 1955.[35] In 1973 news anchorman Chet Huntley created the Big Sky Ski Resort off Gallatin Canyon 40 miles (64 km) south of Bozeman. The resort has grown considerably since 1973 into a residential community and major winter tourist destination.45°16′51″N 111°24′24″W / 45.28083°N 111.40667°W[36]

In 1986 the 60 acres (240,000 m2) site of the Idaho Pole Co. on Rouse Avenue, was designated a Superfund site and placed on the National Priorities List. Idaho Pole treated wood products with creosote and pentachlorophenol on the site between 1945 and 1997.[37]

The Museum of the Rockies was created in 1957 as the gift from Butte physician Caroline McGill and is a part of Montana State University and an affiliate institution of the Smithsonian. It is Montana's premier natural and cultural history museum and houses permanent exhibits on dinosaurs, geology and Montana history, as well as a planetarium and a living history farm. Paleontologist Jack Horner is the museum's curator of palentology and brought national notice to the museum for his fossil discoveries in the 1980s.[38]

Bozeman receives a steady influx of new residents and visitors in part due to its plentiful recreational activities such as fly fishing, hiking, whitewater kayaking, and mountain climbing. Additionally, Bozeman is a gateway community through which visitors pass on the way to Yellowstone National Park and its abundant wildlife and thermal features. The showcasing of spectacular scenery and the western way of life the area received from films set nearby, such as A River Runs Through It and The Horse Whisperer, have also served to draw people to the area.

Twenty-first century

In the past forty years, Bozeman has grown from the sixth- to the fourth-largest city in the state.[39][40] The area attracts new residents due to quality of life, scenery, and nearby recreation. In August 2010, Bozeman was selected by Outside as the best place to live in the west for skiing.[41]

Growth in the Gallatin Valley prompted the Gallatin Airport Authority to authorize a major expansion of the Gallatin Field Airport with two new gates, an expanded passenger screening area, and a third baggage carousel.[42] Gallatin Field was subsequently renamed Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport.[43]

Geography and climate

Bozeman is located at an altitude of 4,820 feet (1,468m).[44] The Bridger Mountains are to the north-northeast, the Tobacco Root Mountains to the west-south-west, the Big Belt Mountains and Horseshoe Hills to the northwest, the Hyalite Peaks of the northern Gallatin Range to the south and the Spanish Peaks of the northern Madison Range to the south-southwest. Bozeman is east of the continental divide, and Interstate 90 passes through the city. It is 84 miles (135 km) east of Butte, 125 miles (201 km) west of Billings, and 93 miles (150 km) north of Yellowstone National Park.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 19.15 square miles (49.60 km2), of which, 19.12 square miles (49.52 km2) is land and 0.03 square miles (0.08 km2) is water.[2]

Bozeman experiences a dry continental climate (Köppen Dfb). Bozeman and the surrounding area receives significantly higher rainfall than much of the central and eastern parts of the state, up to 24 inches (610 mm) of precipitation annually vs. the 8–12" (20–30 cm) common throughout much of Montana east of the Continental Divide.[45] Combined with fertile soils, plant growth is relatively lush. This undoubtedly contributed to the early nickname "Valley of the Flowers" and the establishment of MSU as the state's agricultural college.[46] Bozeman has cold, snowy winters and relatively warm summers, though due to elevation, temperature changes from day to night can be significant. The highest temperature ever recorded in Bozeman was 105 °F (41 °C) on July 31, 1892. The lowest recorded temperature, −43 °F (−42 °C), occurred on February 8, 1936.[47]

| Climate data for Bozeman Montana State University (Western Regional Climate Center station) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

64 (18) |

75 (24) |

83 (28) |

91 (33) |

96 (36) |

105 (41) |

99 (37) |

95 (35) |

88 (31) |

73 (23) |

63 (17) |

105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.7 (−0.2) |

35.5 (1.9) |

42.7 (5.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

63 (17) |

71.6 (22) |

81.3 (27.4) |

80.3 (26.8) |

69.3 (20.7) |

57.6 (14.2) |

42.2 (5.7) |

33.6 (0.9) |

55.23 (12.87) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 21.9 (−5.6) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

32.1 (0.1) |

42.2 (5.7) |

50.7 (10.4) |

58.4 (14.7) |

66.2 (19) |

66.2 (19) |

55.3 (12.9) |

45.3 (7.4) |

32.2 (0.1) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

43.33 (6.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 12.0 (−11.1) |

15.3 (−9.3) |

21.4 (−5.9) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

38.4 (3.6) |

45.2 (7.3) |

51.1 (10.6) |

49.5 (9.7) |

41.2 (5.1) |

32.9 (0.5) |

22.2 (−5.4) |

14.5 (−9.7) |

31.17 (−0.46) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −36 (−38) |

−43 (−42) |

−27 (−33) |

−10 (−23) |

16 (−9) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

26 (−3) |

12 (−11) |

−10 (−23) |

−26 (−32) |

−36 (−38) |

−43 (−42) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.84 (21.3) |

0.70 (17.8) |

1.40 (35.6) |

2.06 (52.3) |

3.22 (81.8) |

2.85 (72.4) |

1.44 (36.6) |

1.48 (37.6) |

1.80 (45.7) |

1.61 (40.9) |

1.10 (27.9) |

0.79 (20.1) |

19.29 (490) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.6 (32) |

10.2 (25.9) |

15.7 (39.9) |

13.1 (33.3) |

4.0 (10.2) |

.5 (1.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.8 (2) |

5.8 (14.7) |

11.6 (29.5) |

11.9 (30.2) |

86.1 (218.7) |

| Source #1: NOAA (normals, 1971–2000)[48] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: The Weather Channel (Records)[49] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 168 | — | |

| 1880 | 894 | 432.1% | |

| 1890 | 2,143 | 139.7% | |

| 1900 | 3,419 | 59.5% | |

| 1910 | 5,187 | 51.7% | |

| 1920 | 6,183 | 19.2% | |

| 1930 | 6,855 | 10.9% | |

| 1940 | 8,665 | 26.4% | |

| 1950 | 11,325 | 30.7% | |

| 1960 | 13,361 | 18.0% | |

| 1970 | 18,670 | 39.7% | |

| 1980 | 21,645 | 15.9% | |

| 1990 | 22,660 | 4.7% | |

| 2000 | 27,509 | 21.4% | |

| 2010 | 37,280 | 35.5% | |

| Est. 2015 | 43,405 | [50] | 16.4% |

| source:[40][51] 2015 Estimate[4] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 37,280 people, 15,775 households, and 6,900 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,949.8 inhabitants per square mile (752.8/km2). There were 17,464 housing units at an average density of 913.4 per square mile (352.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.6% White, 0.5% African American, 1.1% Native American, 1.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.7% from other races, and 2.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.9% of the population.

There were 15,775 households of which 21.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.1% were married couples living together, 7.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 56.3% were non-families. 33.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.17 and the average family size was 2.80.

The median age in the city was 27.2 years. 15.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 28.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 31.4% were from 25 to 44; 16.7% were from 45 to 64; and 8.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 52.6% male and 47.4% female.

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 27,509 people, 10,877 households, and 5,014 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,183.8 people per square mile (843.0/km²). There were 11,577 housing units at an average density of 919.0 per square mile (354.8/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 94.73% White, 0.33% African American, 1.24% Native American, 1.62% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islander, 0.54% from other races, and 1.47% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.59% of the population.

There were 10,877 households out of which 22.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.0% were married couples living together, 7.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 53.9% were non-families. 30.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.85.

In the city the population was spread out with 16.0% under the age of 18, 33.0% from 18 to 24, 28.6% from 25 to 44, 14.4% from 45 to 64, and 8.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 25 years. For every 100 females there were 111.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 112.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,156, and the median income for a family was $41,723. Males had a median income of $28,794 versus $20,743 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,104. About 9.2% of families and 20.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.8% of those under age 18 and 4.4% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Bozeman became an incorporated Montana city in April 1883 and adopted a city council form of government.[53] Currently, the City of Bozeman uses a city commission/city manager form of government which the citizens adopted on January 1, 1922[54] with an elected Municipal Judge. The City Commission is chaired by an elected Mayor. These three entities form the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government.[55]

Departments

- Finance Department – Provides financial administration, treasury and accounting services, grant administration and sustainability management.[56]

- Fire Department – Bozeman is served by the Bozeman Fire Department which is a full-time career fire department. There are currently 39 uniformed firefighters, 3 fire stations, 4 engines (1 reserve), 1 ladder truck, 1 Battalion Suburban, 1 brush truck, 1 HazMat unit, and 1 Medic Unit. The Bozeman Fire Department responded to approximately 3,900 emergency calls in 2014.[57]

- Park, Recreation and Cemetery Department – Operates the Sunset Hills Cemetery, maintains public parks throughout the city to include the East Gallatin Recreation Area and conducts recreational programs for the citizens of Bozeman.[58]

- Public Service Department – Provides engineering, forestry, signs and signals, solid waste, street, vehicle maintenance, water reclamation, water and sewer and water treatment services for the citizens of Bozeman.[59]

Schools

Public

- The Bozeman School District operates one high school-Bozeman High School; two middle schools—Chief Joseph Middle School and Sacajawea Middle School; and eight elementary schools – Emily Dickinson Elementary School, Hawthorne Elementary School, Hyalite Elementary School, Irving Elementary School, Longfellow Elementary School, Meadowlark Elementary School, Morning Star Elementary School, and Whittier Elementary School.[60]

- The district also operates the Bridger Alternative Program as a branch campus of Bozeman High School to serve "at-risk" secondary students.[61]

- The former Emerson Elementary School is now a cultural community center. Willson School, originally a high school, then a middle school, then the base for an alternative high school, is still owned by the school district and houses a number of school district offices.

Private

- Mount Ellis Academy is a co-educational boarding high school (grades 9 through 12) affiliated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church,and Headwaters Academy near the campus of Montana State University.

Media

- Newspapers and Magazines

- Bozeman Avant Courier – published 1871–1905[62]

- The Republican-courier – published 1905–1913[63]

- The Bozeman Courier – publisher 1919–1954[64]

- Bozeman Daily Chronicle is the current local daily paper, owned by Pioneer Newspapers

- Bozeman Magazine is a free monthly publication.

- The BoZone Entertainment and Events Calendar has been publishing since 1993, a free biweekly publication owned by Bozeman Entertainment, LLC

- The Montana Pioneer is a monthly newspaper of some decades' history, based in nearby Livingston but serving both areas.

- AM Radio

- KBOZ 1090, (Talk/Personality), Reier Broadcasting Company

- KOBB 1230, (sports talk), Reier Broadcasting Company

- KPRK AM 1340, (Classic Hits), Townsquare Media

- KMMS 1450, (News/Talk), Townsquare Media

- FM Radio

- KGLT 91.9, (Variety), Montana State University-Bozeman

- KOBB-FM 93.7, (Oldies), Reier Broadcasting Company

- KMMS-FM 95.1, (Adult Album), Townsquare Media

- KISN 96.7, (Top 40 (CHR)), Townsquare Media

- KOZB 97.5, (Classic rock), Reier Broadcasting Company

- KBOZ-FM 99.9, (Country Music), Reier Broadcasting Company

- KXLB 100.7, (Country Music), Townsquare Media

- KBMC (FM) 102.1, (Variety), Montana State University-Billings

- KZMY 103.5, (Hot Adult Contemporary), Townsquare Media

- KBZM 104.7, (Classic Rock), Orion Media LLC

- KKQX 105.7, (Classic Rock), Orion Media LLC

- KSCY 106.9, (Country Music), Orion Media LLC

- Television

- KTVM 6 NBC, Bonten Media Group

- KBZK 7 CBS, Evening Post Publishing Company

- KUSM 9 PBS, Montana State University – Bozeman

- KWYB-LD 28-1 ABC, Max Media (LP relay from Butte)

- KWYB-LD 28-2 FOX

Appearance in art, literature and media

The Bozeman area has served as a filming site for a number of films, including The Wildest Dream,[67] A River Runs Through It, A Plumm Summer and Amazing Grace and Chuck.[68] Aside from being shot in Bozeman, A Plumm Summer featured two local actors, Ben Trotter and John Hosking, as well as many local extras. Films shot in the nearby Paradise Valley south of Livingston and Big Timber areas, such as The Horse Whisperer and Rancho Deluxe also headquartered out of Bozeman due to its status as the largest community in the local trade area.[69]

In popular music, the members of the noise rock group Steel Pole Bath Tub are originally from Bozeman, and wrote a song titled "Bozeman" on their third album, The Miracle of Sound in Motion. The 1980s hard rock band Vixen also featured a former Bozeman resident, Janet Gardner, as lead singer.[70]

Literary references include the Bozeman area and real-life Bozeman artists Bob and Gennie DeWeese[71] as a key setting in Robert Pirsig's novel Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance; the narrator was a professor teaching English composition while developing his philosophical ideas, reflecting the author's own history – Pirsig himself taught at Montana State.[72] John Steinbeck passed through Bozeman via the former U.S. Route 10 as well as venturing into Yellowstone National Park, and recounted his impressions of Montana in Travels with Charley.[73]

Bozeman has been referenced in the science fiction franchise Star Trek, most likely due to the influence of writer Brannon Braga, a native of Bozeman. Per the Star Trek: Enterprise episode "Desert Crossing", the Bozeman area was the fictional site of Earth's first contact with an alien species (the Vulcans) on April 5, 2063 in the film Star Trek: First Contact, though the movie was not filmed in Montana. A starship named the USS Bozeman appears in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Cause and Effect"; it is mentioned in the episode "All Good Things...", the films Star Trek Generations and Star Trek: First Contact, and the First Contact prequel novel Ship of the Line by Diane Carey.

Bozeman was briefly featured in The Big Bang Theory episode "The Bozeman Reaction". It is also featured and mentioned in some episodes of CSI: NY, as the hometown of the character Lindsay Monroe.

National media coverage

On March 5, 2009, the city of Bozeman made national news outlets when an early morning explosion destroyed three buildings in the historic downtown area. Several other buildings were damaged and one person was killed. The blast occurred at about 8:15 a.m. and prompted the evacuation of a two-block area. Investigators found the cause of the explosion to be a leak in a gas line that led to a business that was destroyed in the blast. The gas line was more than 70 years old.[74] Business owners and local residents later filed major lawsuits against Northwestern Energy, the company in charge of the gas line. The suits claimed negligence for the gas leak that led to the blast. As of December 2010, most of the lawsuits against the energy company were settled.[75]

In June of the same year, Bozeman was once again in the national news when it was reported that the city government was requesting that job applicants provide their user names and passwords to social networking sites. A passage from the city's application form said, "Please list any and all current personal or business Web sites, web pages or memberships on any Internet-based chat rooms, social clubs or forums, to include, but not limited to: Facebook, Google, Yahoo, YouTube.com, MySpace, etc."[76]

After the initial news story aired, the Bozeman City Commissioner received e-mails and phone calls expressing indignation about the practice from across the nation. Bozeman residents were astonished and alarmed by the request. The local government believed the practice had been going on as part of a background search for about three years.[77] In response to the negative backlash from the news media and local citizens, the city rescinded the policy on the 20th of June 2009, just two days after making the national news.[78]

Transportation

Bozeman straddles east-west Interstate 90 and is approximately 85 miles (137 km) east of north-south Interstate 15 in Butte, Montana. U.S. Highway 191 connects Bozeman with Big Sky and West Yellowstone to the south. Bozeman is serviced by Montana Rail Link, a privately held, Class II railroad that connects Spokane, Washington with Huntley, Montana. Bozeman has operated a free public bus transportation system called Streamline since 2006.[79] Streamline operates four routes covering the University, Bozeman-Deaconess Hospital, Gallatin Valley Mall, 7th street and 19th street shopping areas, and downtown. The system is funded by a variety of Federal, State, and local sources. The Gallatin Big Sky Transportation District has operated the Skyline between Bozeman and Big Sky since December 2006.[80]

One of the three major regional airports serving southwest Montana is Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport 45°46′39″N 111°09′11″W / 45.77750°N 111.15306°W[81] located 8 miles (13 km) west of Bozeman on the outskirts of Belgrade, Montana. It primarily serves travelers to Bozeman, Big Sky, West Yellowstone and Yellowstone National Park. A smaller commercial airport is located in West Yellowstone, 90 miles (140 km) south of Bozeman.

Notable people

The following individuals are either notable current or former residents of Bozeman (R), were born or raised in Bozeman in their early years (B), or otherwise have a significant connection to the history of the Bozeman area (C).

- Sports personalities

- Conrad Anker, mountaineer C

- Brock Coyle, linebacker for the Seattle Seahawks B

- Dane Fletcher, linebacker for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers B

- Alex Lowe, ice-climber and alpinist R

- Darren Main, yoga instructor R

- Mike McLeod, former National Football League safety B

- Heather McPhie, freestyle skier, member of 2010 US Olympic Team B

- Phil Olsen, former National Football League lineman R

- Willie Saunders, Bozeman-born Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame jockey, won U.S. Triple Crown B

- Tejay van Garderen, professional cyclist R

- Jan Stenerud, member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, AFL and NFL place-kicker for Kansas City Chiefs, Green Bay Packers and Minnesota Vikings; winner of Super Bowl IV R

- Kevin Sweeney, former quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys B

- Military and pioneers

- John Bozeman, pioneer and founder of the Bozeman Trail C

- Henry Comstock, a discoverer of the Comstock Lode died (suicide) in Bozeman on September 29, 1870[82] C

- Gustavus Cheyney Doane, member of Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition 1870 and buried in Sunset Hills Cemetery, Bozeman

- Nelson Story, prominent cattleman and merchant in Bozeman's early years R

- Lester S. Willson, prominent merchant in Bozeman's early years R

- Arts, culture and entertainment

- Kris Atteberry, MLB broadcaster, one of only two Montanans to call an MLB game B

- Brannon Braga, writer and producer of Star Trek television shows and films B

- Deborah Butterfield, sculptor known for use of horses in artwork R

- Gary Cooper, actor, attended Gallatin Valley High School in Bozeman[83] R

- Daniella Deutscher, actress B

- Pablo Elvira, opera singer R

- Landon Jones, journalist and author R

- Donna Kelley, former CNN anchor and current KBZK anchor. R

- Jane Lawrence, actress and opera singer B

- Jason Lytle, lead singer of Modesto band, Grandaddy; solo artist R

- John Mayer, musician, currently resides in a home he purchased "in the Bozeman area" according to an interview on "The Ellen DeGeneres Show"[84] R

- Ben Mikaelsen, author[85] R

- Albert, Alfred and Chris Schlechten multi-generation family of photographers noted for portraiture and images of Yellowstone National Park and the Gallatin Valley.[86] R, R, B

- Christopher Parkening, guitarist, fly casting champion R

- David Quammen, long-time columnist for Outside magazine, and author R

- James Willard Schultz, author and Glacier National Park explorer, lived in Bozeman 1928–29 with partner Jessica McDonald, professor at Montana State; R[87] Schultz's papers are archived at Montana State Burlingame Special Collections Library.[88]

- Michael Spears, actor, calls Bozeman home according to an article from "The Montana Pioneer"[89] R

- Eddie Spears, actor, calls Bozeman home according to an article from "The Montana Pioneer"[89] R

- Julia Thorne, writer and ex-wife of 2004 Democratic Presidential candidate John Kerry R

- Kathy Tyers, writer particularly known for her contribution to the Star Wars series R

- Peter Voulkos, ceramic artist B

- Sarah Vowell, author, regular on This American Life, and voiceover actress, most recognized from The Incredibles,[90][91] B

- Dave Walker, musician R

- Science and academia

- Loren Acton, astronaut and physicist[92] R

- Don G. Despain, botanist, ecologist, and fire behavior specialist R

- Christopher Langan, scientist with one of the highest recorded IQs was born in San Francisco but grew up mostly in Bozeman.

- Diana L. Eck, Professor of Comparative Religion at Harvard University B

- Dr. James A. Henshall, 1st superintendent of the Bozeman Fish Technology Center C[28]

- Alice Haskins, government botanist and professor R [93][94]

- Jack Horner, preeminent paleontologist upon whom the main character, Dr. Alan Grant, in the book and film Jurassic Park was patterned R

- Dale W. Jorgenson, Harvard University professor and economist B

- Robert M. Pirsig, author and past instructor of English and rhetoric at Montana State University R

- Politics, government and business

- Les AuCoin, former U.S. congressman from Oregon R

- John Bohlinger, Lieutenant Governor of Montana B

- Dorothy Bradley, former state legislator, congressional candidate, and gubernatorial candidate[95] R

- Will Brooke, former chief of staff of Conrad Burns R

- Steve Daines, entrepreneur, business leader and Montana's current junior Senator B

- Zales Ecton, Republican politician in the 1930s B

- Charles S. Hartman, United States Congressman from Montana R

- Christopher Hedrick, entrepreneur and international development expert R

- Stan Jones, Libertarian Party candidate for Montana governor and United States Senator R

- Vanessa Kerry, daughter of politician John Kerry R

- Michael McFaul, current United States Ambassador to Russia R

- Scott Sales, former Speaker of the Montana House of Representatives R

- Raymond Strother, Democratic political consultant[96] R

- Sidney Runyan Thomas, judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit B

- Ted Turner, entrepreneur (Ted's Montana Grill) and founder of cable television empires including CNN and TBS[97][98] R

- Philanthropy

- Greg Mortenson, humanitarian and founder of the Central Asia Institute R

- Religion

- Elizabeth Clare Prophet, co-founder of Church Universal and Triumphant R

Business and industry

Bozeman's largest employers include Montana State University – Bozeman 45°40′06″N 111°03′00″W / 45.66833°N 111.05000°W as well as at least two dozen high-tech companies engaged in research or production of lasers and other optical equipment,[99] over a dozen bio-tech companies, and several large software companies.[100] Nationally known companies based in Bozeman include Newport/ILX Lightwave, Quantel USA, RightNow Technologies, Gibson Guitar Corporation, and Simms Fishing Products. Notable non-profit organizations based in Bozeman include the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Human Resource Development Council (HRDC) and Eagle Mount.

Points of interest

- Museums and gardens

- Montana Arboretum and Gardens

- Museum of the Rockies

- American Computer Museum

- Gallatin Historical Society-The Pioneer Museum[101]

- Story Mansion[102]

- Libraries

- Bozeman Public Library[103]

- Renne Library, Montana State University[104]

- Ski areas

- National parks and historic areas

- Universities and colleges

- Other

- Gibson Guitar Factory

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fish Technology Center, established 1892,[27][28]

- Sweet Pea-A Festival of the Arts—Annual festival held in Bozeman annually since 1977. Originally the Sweet Pea Carnival first established in 1906,[105][106]

- Hyalite Canyon and Reservoir

- East Gallatin Recreation Area

Olympic Host Bidding

Bozeman was selected as a potential bid to host the 2026 Winter Olympics.[107]

References

- ↑ "Bozeman, Montana". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- 1 2 "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- 1 2 "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Census 2010 News - U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Montana's 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting".

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

- ↑ http://www.census.gov/popest/data/metro/totals/2012/tables/CBSA-EST2012-01.csv

- ↑ http://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/missoulian.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/3/79/37954978-4f4f-11e0-aaa3-001cc4c03286/4d7fe0c8d7132.pdf.pdf

- ↑ "Bozeman". Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ↑ http://pubpages.unh.edu/~gumprech/Collegetowns.pdf

- ↑ Smith, Phyllis (1996). Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley. A History. Helena, MT: Falcon Press Publishers. pp. 1–2. ISBN 1-56044-540-8.

- ↑ "Lewis and Clark, Bozeman and the Museum of the Rockies". Travel Montana. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ↑ Freeman, Cortlandt L. (1988). The Growing Up Years The First 100 Years of Bozeman as an Incorporated City from 1883 to 1983. Bozeman, MT: Montana Centennial Commission Gallatin County Historical Society. pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Kennedy, Michael S. (1964). "Tall in the Saddle-First Trail Drive to Montana Territory". Cowboys and Cattlemen-A Roundup from Montana The Magazine of Western History. New York: Hastings House Publishing. pp. 103–111.

- ↑ Wellman, Paul I. (1939). "IX-Men Who Didn't Care". The Trampling Herd. Philadelphia, PA: J. P. Lippincott. pp. 94–106.

- ↑ "Fort Ellis". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Smith, Phyllis (1996). Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley. A History. Helena, MT: Falcon Press Publishers. pp. 102–103. ISBN 1-56044-540-8.

- ↑ "Mission Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Siebel, Dennis (1996). Fort Ellis, Montana Territory (1867–1886) – The Fort That Guarded Bozeman. Bozeman, Montana: Gallatin County Historical Association. p. 44.

- ↑ "Fort Elizabeth Meagher". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Putnam, James Bruce (1988). The Evolution of a Frontier Town: Bozeman, Montana and Its Search For Economic Stability 1864–1887. Bozeman, MT: Montana Centennial Commission Gallatin County Historical Society. p. 28.

- ↑ Thomas B. Brook. "Thomas Brook Photographs Collection 771 – Montana State University Libraries". Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- 1 2 Freeman, Cortlandt L. (1988). The Growing Up Years The First 100 Years of Bozeman as an Incorporated City from 1883 to 1983. Bozeman, MT: Montana Centennial Commission Gallatin County Historical Society. p. 67.

- ↑ Smith, Phyllis (1996). Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley. A History. Helena, MT: Falcon Press Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 1-56044-540-8.

- ↑ Mulvaney, Tom (2009). Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-7385-7084-6.

- 1 2 "Fish Technology Center-Outreach". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- 1 2 3 "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Fish Technology Center". Montana River Action. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ↑ Montana State University History "Montana State University History" Check

|url=value (help). Montana State History. Retrieved 2011-01-09. - ↑ Jenks, Jim (2007). A Guide to Historic Bozeman. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. pp. 26–33. ISBN 0-9721522-3-7.

- 1 2 Hurlbut, Brian; Seabring Davis (2009). Insiders' Guide to Yellowstone and Grand Teton. Globe Pequot. pp. 179–181. ISBN 978-0-7627-5041-2.

- ↑ Jenks, Jim (2007). A Guide to Historic Bozeman. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-9721522-3-7.

- ↑ "Bridger Bowl Ski Area". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Bridger Bowl Association". Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ Jenks, Jim (2007). A Guide to Historic Bozeman. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-9721522-3-7.

- ↑ "Big Sky Ski Resort". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Superfund Program-Idaho Pole Co.". Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- ↑ "Museum of the Rockies to become Smithsonian affiliate". Helena Independent Record. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2012. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- 1 2 "Bozeman (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Quickfacts.census.gov. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ↑ "Best Towns 2010". Outside Magazine. Archived from the original on January 14, 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ "Airport Expansion Ramping Up-October 28, 2009". Bozeman Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ Bacaj, Jason (December 9, 2011). "Gallatin Airport Authority approves airport name change". Bozeman Daily Chronicle. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Bozeman, Montana". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Bozeman Series". National Cooperative Soil Survey. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Montana State University History". Montana State University. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Bozeman, Montana Period of Record Daily Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Climatography of the United States NO.81" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Monthly Averages for Bozeman, MT". The Weather Channel. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 128.

- ↑ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ↑ Freeman, Cortlandt L. (1988). The Growing Up Years The First 100 Years of Bozeman as an Incorporated City from 1883 to 1983. Bozeman, MT: Montana Centennial Commission Gallatin County Historical Society. pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Freeman, Cortlandt L. (1988). The Growing Up Years The First 100 Years of Bozeman as an Incorporated City from 1883 to 1983. Bozeman, MT: Montana Centennial Commission Gallatin County Historical Society. p. 77.

- ↑ "Bozeman City Government". City of Bozeman. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "City of Bozeman Finance Department". City of Bozeman. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ↑ "Bozeman Fire Department". City of Bozeman. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ "City of Bozeman Parks, Recreation and Cemetery Department". Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ↑ "City of Bozeman Public Services Department". City of Bozeman. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Bozeman School District-Our Schools". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-12.

- ↑ "Bozeman School District-High Schools". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-12.

- ↑ "About Bozeman Avant Courier". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ↑ "About The Republican Courier". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ↑ "About The Bozeman Courier". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- 1 2 "Radio Stations near the city of Bozeman MT". OnTheRadio.net. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ↑ "Butte-Bozeman TV Stations". Station Index-The Broadcasting Website. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ↑ "The Wildest Dream". MoviesPlanet. Archived from Location info the original Check

|url=value (help) on March 24, 2012. Retrieved 2011-01-09. - ↑ "Movies made in Montana". MontanaKids.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ↑ "Feature films shot in Montana". Film Montana Office. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ "Big Sky Conference". Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Henry Gurr presentation". Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Robert M. Pirsig´s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and the term ´Chautauqua´". Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Travels Without Charley – Montana: Love at first sight". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. October 24, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ Robbins, Jim (17 March 2009). "Fatal Blast Wounds a City to Its Core". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Boyce, Dan (December 9, 2010). "Most lawsuits against NorthWestern Energy for downtown Bozeman explosion settled". KTVQ. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Gouras, Matt (19 June 2009). "Montana City Asks Job Applicants For Facebook passwords". Huffington Post. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Heussner, Kimae (19 June 2009). "Montana City Asks Jobb Applicants for Online Passwords". ABC News. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Weinstein, Natalie (20 June 2009). "Bozeman to job seekers: We won't seek passwords". CNET. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ "Streamline". Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Skyline bus service schedule between Bozeman and Big Sky announced". Montana State University News Service. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ "Gallatin Field Airport". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Stout, Tom (1921). History of Montana. I. New York: American Historical Society. p. 322.

- ↑ "Gary Cooper-Cool Montana Stories". Montanakids.com. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ Browning, Skylar (May 15, 2012). "John Mayer now lives in Montana | Indy Blog". Missoulanews.bigskypress.com. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ↑ Author Ben Mikaelsen Archived February 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Photo Archives - Museum of the Rockies".

- ↑ Hanna, Warren L. (1986). "Life with Apaki". The Life and Times of James Willard Schultz (Apikuni). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 233–248. ISBN 0-8061-1985-3.

- ↑ "Collection 10 – James Willard Schultz Papers, 1867–1969". MSU Libraries. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- 1 2 ["Native Stars: The Spears Brothers- Rising Stars Call Bozeman Home" The Montana Pioneer, http://www.mtpioneer.com/2012-February-Native-Stars.html February 2014.

- ↑ "Sarah Vowell". transom.org. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ "Sarah Vowell-Author of The Partly Cloudy Patriot talks with Robert Birnbaum". identitytheory.com. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ "MSU PHYSICS FACULTY - LOREN ACTON". montana.edu.

- ↑ "Biographies". The Smith Alumnae Quarterly. Smith College. 30-31: 444. 1938. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ↑ "List of members of the American Phytopathological Society". Phytopathology. 3: 330. 1913.

- ↑ "Ex-lawmaker Dorothy Bradley named to NorthWestern board, Missoulian Online, April 22, 2009, accessed June 29, 2009

- ↑ "Raymond Strother: Political Strategist/Author (1940)". Museum of the Gulf Coast. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Turner Enterprises, Ranches FAQ Archived April 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ted Turner grand marshal of Livingston parade" Great Falls Tribune, June 26, 2009

- ↑ "Montana optics-related companies".

- ↑ "High-tech clusters spur growth in western Montana". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ↑ "Gallatin Historical Society-The Pioneer Museum". Gallatin Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Story Mansion History". Friends of the Story Mansion. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ "Bozeman Public Library". Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Montana State University Libraries". Retrieved 2011-01-10.

- ↑ "Sweet Pea-History". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- ↑ Smith, Phyllis (1997). Sweet Pea Days: A History. Bozeman, MT: Gallatin County Historical Society. p. 1.

- ↑ "Bozeman 2026". Retrieved 2016-03-10.#

Further reading

- Burlingame, Merrill G. (1976). Gallatin County Heritage-A Report of Progress 1805–1976. Gallatin County Bicentennial Committee.

- Putnam, James Bruce (1988). The Evolution of a Frontier Town: Bozeman, Montana and Its Search For Economic Stability 1864–1887. Bozeman, MT: Montana Centennial Commission Gallatin County Historical Society.

- Freeman, Cortlandt L. (1988). The Growing Up Years The First 100 Years of Bozeman as an Incorporated City from 1883 to 1983. Bozeman, MT: Montana Centennial Commission Gallatin County Historical Society.

- Bates, Grace (1994). Gallatin County-Places and Things Present and Past. Gallatin County Historical Society. ISBN 0-930401-78-6.

- Smith, Phyllis (1996). Bozeman Names Have A History. Bozeman, MT: Gallatin County Historical Society.

- Smith, Phyllis (1996). Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley. A History. Helena, MT: Falcon Press Publishers. ISBN 1-56044-540-8.

- Smith, Phyllis (1997). Sweet Pea Days: A History. Bozeman, MT: Gallatin County Historical Society.

- Jenks, Jim (2007). A Guide to Historic Bozeman. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-9721522-3-7.

- Malloy, Denise Glaser (2008). Images of America-Bozeman. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-4844-9.

- Mulvaney, Tom (2009). Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7084-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bozeman, Montana. |

- Official website

- Chamber of Commerce

- Convention and Visitors' Bureau

- Bozeman Public Schools

- Gallatin County Emergency Management

- Gallatin County Genealogical Society

![]() Bozeman travel guide from Wikivoyage

Bozeman travel guide from Wikivoyage