Edward Watkin

Sir Edward William Watkin, 1st Baronet (26 September 1819 – 13 April 1901) was a British Member of Parliament, railway and cable car entrepreneur. He was an ambitious visionary, and presided over large-scale railway engineering projects to fulfil his business aspirations, eventually rising to become chairman of nine different British railway companies.

Among his more notable projects were his expansion of the Metropolitan Railway (part of today's London Underground network); the construction of the Great Central Main Line, a purpose-built high-speed railway line; the creation of a pleasure gardens with a partially constructed iron tower at Wembley and a failed attempt to dig a channel tunnel under the English Channel to connect his railway empire to the French rail network.[1]

Biography

Watkin was born in Salford, Lancashire, the son of wealthy cotton merchant Absalom Watkin,[2] who was noted for his involvement in the Anti-Corn Law League.

After a private education, he went to work in his father's mill business.[3] In 1845 at age 26 he founded the Manchester Examiner, by which time he had become a partner in his father's business.

He lived at Rose Hill, Northenden, a suburb of Manchester, in a house bought by his father in 1832.[4] He is buried in St Wilfrid's churchyard in Northenden, where a memorial plaque commemorates his life.

Railways

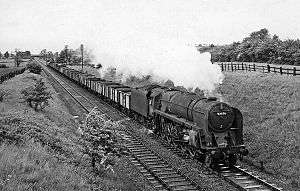

Watkin began to show an interest in railways and in 1845 he took on the secretaryship of the Trent Valley Railway, which was sold the following year to the London and North Western Railway (LNWR), for £438,000.[5] He then became assistant to Captain Mark Huish, general manager of the LNWR. He visited USA and Canada and in 1852 he published a book about the railways in these countries. Back in Great Britain he was appointed secretary of the Worcester & Hereford Railway. He then left the LNWR and in 1853 became the general manager of the Manchester Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR).[6] He held this position to 1862, and was chairman of the company from 1864 to 1894.[7] He was knighted in 1868 and made a baronet in 1880.[8]

Abroad, he encouraged the uniting of the Canadian provinces by the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. He also helped to build the railway between Athens and Piraeus, advised on the Indian railways and organised transport in the Belgian Congo.

Watkin was involved with other railway companies. In 1866 he became a director of the Great Western Railway and later the Great Eastern Railway. By 1881 he was a director of nine railways and trustee of a tenth. These included the Cheshire Lines, the East London, the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire, the Manchester, South Junction & Altrincham, the Metropolitan, the Oldham, Ashton & Guide Bridge, the Sheffield & Midland Joint, the South Eastern, the Wigan Junction and the New York, Lake Erie and Western railways.

He was instrumental in the creation of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway's (MS&LR) 'London Extension', Sheffield to Marylebone, the Great Central Main Line, opened in 1899.[9]

Channel Tunnel

For Watkin, opening an independent route to London was crucial for the long-term survival and development of the MS&LR, but it was also one part of a grander scheme: a line from Manchester to Paris.[9] His chairmanships of the South Eastern Railway, the Metropolitan Railway,[7] in addition to the MS&LR meant that he controlled railways from England's south coast ports, through London and (with the London Extension) through the Midlands to the industrial cities of the North; he was also on the board of the Chemin de Fer du Nord, a French railway company based in Calais. Watkin's ambitious plan was to develop a railway network which could run passenger trains directly from Liverpool and Manchester to Paris, crossing from Britain to France via a tunnel under the English Channel.[10] As well as a high-speed specification, the Great Central Main Line was also built to an expanded continental loading gauge; unlike any other railway lines in Britain, Watkin's line would be able to accommodate larger-sized continental trains crossing from France.[11]

Watkin started his tunnel works with the South Eastern Railway in 1880–81. Digging began at Shakespeare Cliff between Folkestone and Dover and reached a length of 2,020 yards (1,850 m). The project was highly controversial and fears grew of the tunnel being used as a route for a possible French invasion of Great Britain; notable opponents of the project were the War Office Scientific Committee, Lord Wolseley and Prince George, Duke of Cambridge;[12] Queen Victoria reportedly found the tunnel scheme "objectionable". Watkin was skilled at public relations and attempted to garner political support for his project, inviting such high-profile guests as the Prince and Princess of Wales, Liberal Party Leader William Gladstone and the Archbishop of Canterbury to submarine champagne receptions in the tunnel.[1] In spite of his attempts at winning support, his tunnel project was blocked by parliament and cancelled in the interests of national security. The original entrance to Watkin's tunnel works remains in the cliff face but is now closed for safety reasons.[13][14]

Politics

Watkin was Liberal Member of Parliament for the constituencies of Great Yarmouth (1857–1858) Stockport (1864–1868) and Hythe in Kent (1874–1895). He was High Sheriff of Cheshire in 1874.[15]

Wembley Park and Watkin's Tower

Watkin's last project was the construction of a large iron tower, called Watkin's Tower, in Wembley Park, north-west London. The 1,200-foot (370 m) tower was to be the centrepiece of a large public amusement park which he opened in May 1894 to attract London passengers onto his Metropolitan Railway. The park was served by Wembley Park station, which officially opened in the same month, though it had in fact been open on Saturdays since October 1893 to cater for football matches in the pleasure gardens.

Watkin's vision of Wembley Park as a day-out destination for Londoners had far reaching consequences, shaping the history and use of the area to the present day. Without Watkin's pleasure gardens and station it is unlikely that the British Empire Exhibition would have been held at Wembley, which in turn would have prevented Wembley becoming either synonymous with English football or a successful popular music venue. Without Watkin, it is likely that the district would have simply become inter-war semi-detached suburbia like the rest of west London.

The tower was intended to rival the Eiffel Tower in Paris.[1][16] The foundations of the tower were laid in 1892, the first stage was completed in September 1895 and it was opened to the public in 1896.[17]

After an initial burst of popularity, the tower failed to draw large crowds. Of the 100,000 visitors to the Park in 1896 rather less than a fifth paid to go up the Tower. Furthermore, the marshy site proved unsuitable for such a structure. Whether the original design (which was to have had eight legs) would have distributed the weight more evenly cannot be known, but by 1896 the four-legged tower was clearly tilting. In addition, Watkin had retired from the chairmanship of the Metropolitan in 1894 after suffering a stroke, so the tower’s enthusiastic champion was gone. In June 1897 the tower was illuminated for Queen Victoria's 60th Jubilee, but it was never extended beyond the first stage.

In 1902 the Tower, now known as ‘Watkin's Folly’, was declared unsafe (though this was because of concerns about the safety of the lifts, rather than directly about the subsidence) and closed to the public. In 1904 it was decided to demolish the structure, a process that ended with the foundations being destroyed by explosives in 1907, leaving four large holes in the ground.[1][17][18][19][20] The Empire Stadium (today's Wembley Stadium) was built on the site in 1923.

Other schemes

Watkin was responsible for an abortive attempt in the 1880s to create a new south-coast resort and deep-water port at Dungeness in Kent.

Family

Watkin married Mary Briggs in 1845;[21] their son Alfred Mellor Watkin was locomotive superintendent of the South Eastern Railway in 1876[22] and Member of Parliament for Great Grimsby (UK Parliament constituency) in 1877.[21] His nephew Edward Watkin was general manager of the Hull and Barnsley Railway.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Goffin, Magdalen (2005). "4. The Watkin path". The Watkin path : an approach to belief. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 23–25. ISBN 9781845191283. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para. 1.

- ↑ Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para. 2.

- ↑ The Buildings of England: Lancashire-Manchester and the South-East

- ↑ Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para.3.

- ↑ Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para. 3.

- 1 2 Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para.5.

- ↑ Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para.4, 10.

- 1 2 Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para.6.

- ↑ Haywood, Russell (2012). Railways, Urban Development and Town Planning in Britain: 1948–2008. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 9781409488255.

- ↑ Healy 1987, pp. 24–53.

- ↑ Hadfield-Amkhan, Amelia (2010). "4. The 1882 channel Tunnel Crisis". British foreign policy, national identity, and neoclassical realism. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 67–72. ISBN 9781442205468.

- ↑ "Channel Tunnel – Yes Or No?". 1957. British Pathé. Retrieved 6 September 2013. Missing or empty

|series=(help) - ↑ Horsfall Turner, Olivia (2013). "Making Connections". Dreaming the Impossible: Unbuilt Britain. British Broadcasting Corporation. BBC Four.

- ↑ Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para.10.

- ↑

- Lynde, Fred. C. (1890). "Design No. 37". Descriptive Illustrated Catalogue of the Sixty-Eight Competitive Designs for the Great Tower for London. London: The Tower Company/Industries. pp. 82–83. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- 1 2 Hewlett, Geoffrey (1979). A History of Wembley. Brent Library Service. pp. 170–1.

- ↑ Greaves, John Neville (2014). Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901 The Last of the Railway Kings. Melrose Books. p. 203. ISBN 1909757322.

- ↑ Hodgkins, David (2002). The Second Railway King: The Life and Times of Sir Edward Watkin 1819-1901. Merton Priory Press. p. 652. ISBN 1898937494.

- ↑ Rowley, Trevor (2006). The English landscape in the twentieth century. London [u.a.]: Hambledon Continuum. pp. 405–7. ISBN 9781852853884.

- 1 2 Sutton & Bagwell 2004, para.11.

- ↑ Biographical details of managers, chairmen, etc

References

- Hartwell, Clare, Hyde, Matthew and Pevsner, Nikolaus, The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Manchester and the South East (2004) Yale University Press

- Healy, John (1987). Echoes of the Great Central. Greenwich Editions. ISBN 0-86288-076-9.

- Dyckhoff, Nigel. Portrait of the Cheshire Lines Committee, Ian Allan, Shepperton, 1999 ISBN 978-0-7110-2521-9

Biographical articles

- Sutton, C. W.; Bagwell, P. S. (2004), "Watkin, Sir Edward William, first baronet (1819–1901), railway promoter", The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36762

- David Hodgkins (2002), The Second Railway King – The Life and Times of Sir Edward Watkin 1819–1901, Merton Priory Press, ISBN 1-898937-49-4

- Kirsty Elleray (4 December 2002), "The nearly man of Northenden", menmedia.co.uk, The South Manchester Reporter

- John Greaves (Summer 2007), "Sir Edward Watkin and the Liberal cause in the Nineteenth Century" (PDF), Journal of Liberal History (55): 25–27

- John Speller, "Sir Edward Watkin", spellerweb.net

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Watkin. |

- Works by Edward Watkin at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edward Watkin at Internet Archive

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Edward Watkin

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles Edmund Rumbold Sir Edmund Lacon |

Member of Parliament for Great Yarmouth 1857 – August 1857 With: William Torrens McCullagh |

Succeeded by Adolphus William Young John Mellor |

| Preceded by James Kershaw John Benjamin Smith |

Member of Parliament for Stockport 1864–1868 With: John Benjamin Smith |

Succeeded by William Tipping John Benjamin Smith |

| Preceded by Baron Amschel de Rothschild |

Member of Parliament for Hythe 1874–1895 |

Succeeded by Sir James Bevan Edwards |

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New title | Baronet (of Rose Hill) 1880–1901 |

Succeeded by Alfred Mellor Watkin |