Dehydroepiandrosterone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection (as prasterone enanthate) |

| ATC code |

A14AA07 (WHO) G03EA03 (WHO) (combination with estrogen) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Biological half-life | 12 hours |

| Excretion | Urinary:?% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | (3β)-3-Hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one, 5,6-didehydroepiandrosterone,[1] androst-5-en-3β-ol-17-one |

| CAS Number |

53-43-0 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5881 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 2370 |

| DrugBank |

DB01708 |

| ChemSpider |

5670 |

| UNII |

459AG36T1B |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:28689 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL90593 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 288.424 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Melting point | 148.5 °C (299.3 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), also known as androstenolone or prasterone, is an endogenous steroid hormone.[2] It is the most abundant circulating steroid hormone in humans,[3] in whom it is produced in the adrenal glands,[4] the gonads, and the brain,[5] where it functions predominantly as a metabolic intermediate in the biosynthesis of the androgen and estrogen sex steroids.[2][6] However, DHEA also has a variety of potential biological effects in its own right, binding to an array of nuclear and cell surface receptors,[7] and acting as a neurosteroid.[8]

Medical uses

In women with adrenal insufficiency and the healthy elderly there is insufficient evidence to support the use of DHEA.[9][10]

Menopause

DHEA is sometimes used as an androgen in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for menopause. A long-lasting ester prodrug of DHEA, prasterone enanthate, is used in combination with estradiol valerate for this indication.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

Cancer

There is no evidence DHEA is of benefit in treating or preventing cancer.[17] Although DHEA is postulated as an inhibitor towards glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and suppresses leukemia cell proliferation in vitro,[18][19] DHEA may enhance G6PD mRNA expression, confounding its inhibitory effects.[20]

Strength

Evidence is inconclusive in regards to the effect of DHEA on strength in the elderly.[21]

In middle-aged men, no significant effect of DHEA supplementation on lean body mass, strength, or testosterone levels was found in a randomized placebo-controlled trial.[22]

Memory

DHEA supplementation has not been found to be useful for memory function in normal middle aged or older adults.[23] It has been studied as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease, but there is no evidence that it is effective.[24]

Cardiovascular disease

A review in 2003 found the then-extant evidence sufficient to suggest that low serum levels of DHEA-S may be associated with coronary heart disease in men, but insufficient to determine whether DHEA supplementation would have any cardiovascular benefit.[25]

Lupus

There is some evidence of short-term benefit in those with systemic lupus erythematosus but little evidence of long-term benefit or safety.[26]

Body composition

A meta-analysis of intervention studies shows that DHEA supplementation in elderly men can induce a small but significant positive effect on body composition that is strictly dependent on DHEA conversion into its bioactive metabolites such as androgens or estrogens.[27]

Side effects

DHEA is produced naturally in the human body, but the long-term effects of its use are largely unknown.[17][28] In the short term, several studies have noted few adverse effects. In a study by Chang et al., DHEA was administered at a dose of 200 mg/day for 24 weeks with slight androgenic effects noted.[29] Another study utilized a dose up to 400 mg/day for 8 weeks with few adverse events reported.[30] A longer term study followed patients dosed with 50 mg of DHEA for 12 months with the number and severity of side effects reported to be small.[31] Another study delivered a dose of 50 mg of DHEA for 10 months with no serious adverse events reported.[32]

As a hormone precursor, there has been a smattering of reports of side effects possibly caused by the hormone metabolites of DHEA.[28][33]

It is not known whether DHEA is safe for long-term use. Some researchers believe DHEA supplements might actually raise the risk of breast cancer, prostate cancer, heart disease, diabetes,[28] and stroke. DHEA may stimulate tumor growth in types of cancer that are sensitive to hormones, such as some types of breast, uterine, and prostate cancer.[28] DHEA may increase prostate swelling in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), an enlarged prostate gland.[17]

DHEA is a steroid hormone. High doses may cause aggressiveness, irritability, trouble sleeping, and the growth of body or facial hair on women.[17] It also may stop menstruation and lower the levels of HDL ("good" cholesterol), which could raise the risk of heart disease.[17] Other reported side effects include acne, heart rhythm problems, liver problems, hair loss (from the scalp), and oily skin. It may also alter the body's regulation of blood sugar.[17]

DHEA should not be used with tamoxifen, as it may promote tamoxifen resistance.[17] Patients on hormone replacement therapy may have more estrogen-related side effects when taking DHEA. This supplement may also interfere with other medicines, and potential interactions between it and drugs and herbs should be considered. Always tell your doctor and pharmacist about any supplements and herbs you are taking.[17]

DHEA is possibly unsafe for individuals experiencing the following conditions: pregnancy and breast-feeding, hormone sensitive conditions, liver problems, diabetes, depression or mood disorders, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), or cholesterol problems.[34] Individuals experiencing any of these conditions should consult with a doctor before taking.

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) is the sulfate ester of DHEA. This conversion is reversibly catalyzed by sulfotransferase (SULT2A1) primarily in the adrenals, the liver, and small intestine. In the blood, most DHEA is found as DHEAS with levels that are about 300 times higher than those of free DHEA. Orally ingested DHEA is converted to its sulfate when passing through intestines and liver. Whereas DHEA levels naturally reach their peak in the early morning hours, DHEAS levels show no diurnal variation. From a practical point of view, measurement of DHEAS is preferable to DHEA, as levels are more stable.

Production

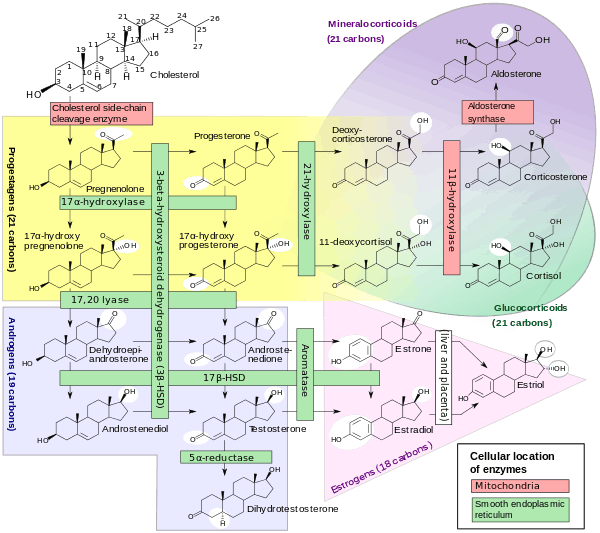

DHEA is produced from cholesterol through two cytochrome P450 enzymes. Cholesterol is converted to pregnenolone by the enzyme P450 scc (side chain cleavage); then another enzyme, CYP17A1, converts pregnenolone to 17α-hydroxypregnenolone and then to DHEA.[36]

Mechanism of action

Although it predominantly functions as an endogenous precursor to more potent androgens such as testosterone and DHT, DHEA has been found to possess some degree of androgenic activity in its own right, acting as a low affinity (Ki = 1 μM), weak partial agonist of the androgen receptor. However, its intrinsic activity at the receptor is quite weak, and on account of that, due to competition for binding with full agonists like testosterone, it can actually behave more like an antagonist depending on circulating testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels, and hence, like an antiandrogen. However, its affinity for the receptor is very low, and for that reason, is unlikely to be of much significance under normal circumstances.[37][38]

In addition to its affinity for the androgen receptor, DHEA has also been found to bind to and activate the ERα and ERβ estrogen receptors with Ki values of 1.1 μM and 0.5 μM, respectively, and EC50 values of >1 μM and 200 nM, respectively. Though it was found to be a partial agonist of the ERα with a maximal efficacy of 30–70%, the concentrations required for this degree of activation make it unlikely that the activity of DHEA at this receptor is physiologically meaningful. Remarkably however, DHEA acts as a full agonist of the ERβ with a maximal response similar to or actually slightly greater than that of estradiol, and its levels in circulation and local tissues in the human body are high enough to activate the receptor to the same degree as that seen with circulating estradiol levels at somewhat higher than their maximal, non-ovulatory concentrations; indeed, when combined with estradiol with both at levels equivalent to those of their physiological concentrations, overall activation of the ERβ was doubled. As such, it has been proposed that DHEA may be an important and potentially major endogenous estrogen in the body.[7][37]

Unlike the case of the androgen and estrogen receptors, DHEA does not bind to or activate the progesterone, glucocorticoid, or mineralocorticoid receptors.[37][39]

Other nuclear receptor targets of DHEA include the PPARα, PXR, and CAR. In addition, it has been found to directly act on several membrane receptors, including the NMDA receptor as a positive allosteric modulator, the GABAA receptor as a negative allosteric modulator, and the σ1 receptor as an agonist. It is these actions that have conferred the label of a "neurosteroid" upon DHEA. Finally, DHEA is thought to regulate a handful of other proteins via indirect, genomic mechanisms, including the enzymes P4502C11 and 11β-HSD1—the latter of which is essential for the biosynthesis of the glucocorticoids such as cortisol and has been suggested to be involved in the antiglucocorticoid effects of DHEA—and the carrier IGFBP1.[37][40]

Biological role

DHEA and other adrenal androgens such as androstenedione, although relatively weak androgens, are responsible for the androgenic effects of adrenarche, such as early pubic and axillary hair growth, adult-type body odor, increased oiliness of hair and skin, and mild acne.[41][42][43] Women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS), who have a non-functional androgen receptor (AR) and are immune to the androgenic effects of DHEA and other androgens, have absent or only sparse/scanty pubic and axillary hair and body hair in general, demonstrating the role of DHEA, testosterone, and other androgens in body hair development at both adrenarche and pubarche.[44][45][46][47]

As a neurosteroid, DHEA has important effects on neurological and psychological functioning.[48][49][50]

Measurement

As almost all DHEA is derived from the adrenal glands, blood measurements of DHEAS/DHEA are useful to detect excess adrenal activity as seen in adrenal cancer or hyperplasia, including certain forms of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome tend to have elevated levels of DHEAS.[51]

Increasing endogenous production

Regular exercise is known to increase DHEA production in the body.[52][53] Calorie restriction has also been shown to increase DHEA in primates.[54] Some theorize that the increase in endogenous DHEA brought about by calorie restriction is partially responsible for the longer life expectancy known to be associated with calorie restriction.[55] Catalpol and a combination of acetyl-carnitine and propionyl-carnitine on 1:1 ratio also improves endogenous DHEA production and release due to direct cholinergic stimulation of CRH release and an increase of IGF-1 expression respectively.

Chemistry

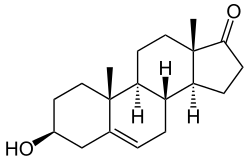

DHEA is an androstane steroid and is known chemically as androst-5-en-3β-ol-17-one. It is the 5-dehydro analogue of epiandrosterone (5α-androstan-3β-ol-17-one) and is also known as 5-dehydroepiandrosterone or as δ5-epiandrosterone.

Isomers

The term "dehydroepiandrosterone" is ambiguous chemically because it does not include the specific positions within epiandrosterone at which hydrogen atoms are missing. DHEA itself is 5,6-didehydroepiandrosterone or 5-dehydroepiandrosterone. A number of naturally occurring isomers also exist and may have similar activities. Some isomers of DHEA are 1-dehydroepiandrosterone (1-androsterone) and 4-dehydroepiandrosterone. These isomers are also technically "DHEA", since they are dehydroepiandrosterones in which hydrogens are removed from the epiandrosterone skeleton.

Society and culture

Legality

United States

DHEA is legal to sell in the United States as a dietary supplement. It is currently grandfathered in as an "Old Dietary Ingredient" being on sale prior to 1994. DHEA is specifically exempted from the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 1990 and 2004.[56] It is banned from use in athletic competition.

Canada

In Canada, DHEA is a Controlled Drug listed under Section 23 of Schedule IV of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act[57] and as such is available by prescription only.

Australia

In Australia, a prescription is required to buy DHEA, where it is also comparatively expensive compared to off-the-shelf purchases in US supplement shops. Australian customs classify DHEA as an "anabolic steroid[s] or precursor[s]" and, as such, it is only possible to carry DHEA into the country through customs if one possesses an import permit which may be obtained if one has a valid prescription for the hormone.[58]

UK

DHEA (Prasterone) is listed as an anabolic steroid and is thus a class C controlled drug.

Sports and athletics

DHEA is a prohibited substance under the World Anti-Doping Code of the World Anti-Doping Agency,[59] which manages drug testing for Olympics and other sports. In January 2011, NBA player O.J. Mayo was given a 10-game suspension after testing positive for DHEA. Mayo termed his use of DHEA as "an honest mistake," saying the DHEA was in an over-the-counter supplement and that he was unaware the supplement was banned by the NBA.[60] Mayo is the seventh player to test positive for performance-enhancing drugs since the league began testing in 1999. Rashard Lewis, then with the Orlando Magic, tested positive for DHEA and was suspended 10 games before the start of the 2009-10 season.[61] 2008 Olympic 400 meter champion Lashawn Merritt has also tested positive for DHEA and was banned from the sport for 21 months.[62] Yulia Efimova, who holds the world record pace for both the 50-meter and 200-meter breaststroke, and won the bronze medal in the 200-meter breaststroke in the 2012 London Olympic Games, tested positive for DHEA in an out-of-competition doping test.[63] In 2016 MMA fighter Fabio Maldonado revealed he was taking DHEA during his time with the UFC.[64]

Marketing

In the United States, DHEA or DHEA-S have been advertised with claims that they may be beneficial for a wide variety of ailments. DHEA and DHEA-S are readily available in the United States, where they are marketed as over-the-counter dietary supplements.[65]

See also

- 3α-Androstanediol

- Androsterone

- Etiocholanolone

- List of unproven and disproven cancer treatments

- Pregnenolone sulfate

References

- ↑ James Devillers (27 April 2009). Endocrine Disruption Modeling. CRC Press. pp. 339–. ISBN 978-1-4200-7636-3.

- 1 2 Mo Q, Lu SF, Simon NG (April 2006). "Dehydroepiandrosterone and its metabolites: differential effects on androgen receptor trafficking and transcriptional activity". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 99 (1): 50–8. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.11.011. PMID 16524719.

- ↑ William F Ganong MD, 'Review of Medical Physiology', 22nd Ed, McGraw Hill, 2005, p. 362.

- ↑ The Merck Index, 13th Edition, 7798

- ↑ Schulman, Robert A.; Dean, Carolyn (2007). Solve It With Supplements. New York City: Rodale, Inc. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-57954-942-8.

DHEA (Dehydroepiandrosterone) is a common hormone produced in the adrenal glands, the gonads, and the brain.

- ↑ Thomas Scott (1996). Concise Encyclopedia Biology. Walter de Gruyter. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-11-010661-9. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- 1 2 Webb SJ, Geoghegan TE, Prough RA, Michael Miller KK (2006). "The biological actions of dehydroepiandrosterone involves multiple receptors". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 38 (1–2): 89–116. doi:10.1080/03602530600569877. PMC 2423429

. PMID 16684650.

. PMID 16684650. - ↑ Friess E, Schiffelholz T, Steckler T, Steiger A (December 2000). "Dehydroepiandrosterone--a neurosteroid". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 30 Suppl 3: 46–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.0300s3046.x. PMID 11281367.

- ↑ Arlt, W (September 2004). "Dehydroepiandrosterone and ageing". Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 18 (3): 363–80. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2004.02.006. PMID 15261843.

- ↑ Alkatib, AA; Cosma, M; Elamin, MB; Erickson, D; Swiglo, BA; Erwin, PJ; Montori, VM (October 2009). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials of DHEA treatment effects on quality of life in women with adrenal insufficiency". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 94 (10): 3676–81. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0672. PMID 19773400.

- ↑ https://www.drugs.com/international/gynodian-depot.html

- ↑ J. Horsky; J. Presl (6 December 2012). Ovarian Function and its Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9.

- ↑ D. Platt (6 December 2012). Geriatrics 3: Gynecology · Orthopaedics · Anesthesiology · Surgery · Otorhinolaryngology · Ophthalmology · Dermatology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-3-642-68976-5.

- ↑ S. Campbell (6 December 2012). The Management of the Menopause & Post-Menopausal Years: The Proceedings of the International Symposium held in London 24–26 November 1975 Arranged by the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of London. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 395–. ISBN 978-94-011-6165-7.

- ↑ Carrie Bagatell; William J. Bremner (27 May 2003). Androgens in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-1-59259-388-0.

- ↑ Frigo P, Eppel W, Asseryanis E, Sator M, Golaszewski T, Gruber D, Lang C, Huber J (1995). "The effects of hormone substitution in depot form on the uterus in a group of 50 perimenopausal women--a vaginosonographic study". Maturitas. 21 (3): 221–5. PMID 7616871.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ades TB, ed. (2009). DHEA. American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Complementary and Alternative Cancer Therapies (2nd ed.). American Cancer Society. pp. 729–33. ISBN 9780944235713.

- ↑ Di Monaco M, Pizzini A, Gatto V, Leonardi L, Gallo M, Brignardello E, Boccuzzi G (1997). "Role of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibition in the antiproliferative effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on human breast cancer cells". Br J Cancer. 75: 589–92. PMID 9052415.

- ↑ Xu SN, Wang TS, Li X, Wang YP (Sep 2016). "SIRT2 activates G6PD to enhance NADPH production and promote leukaemia cell proliferation". Sci Rep. 6: 32734. doi:10.1038/srep32734. PMID 27586085.

- ↑ Hecker PA, Leopold JA, Gupte SA, Recchia FA, Stanley WC (Feb 2013). "Impact of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency on the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease". Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 304: H491–500. PMID 23241320.

- ↑ Baker, WL; Karan, S; Kenny, AM (June 2011). "Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on muscle strength and physical function in older adults: a systematic review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 59 (6): 997–1002. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03410.x. PMID 21649617.

- ↑ Wallace, M. B.; Lim, J.; Cutler, A.; Bucci, L. (1999). "Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone vs androstenedione supplementation in men". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 31 (12): 1788–92. doi:10.1097/00005768-199912000-00014. PMID 10613429.

- ↑ Grimley Evans, J; Malouf, R; Huppert, F; van Niekerk, JK (Oct 18, 2006). Malouf, Reem, ed. "Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation for cognitive function in healthy elderly people". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (4): CD006221. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006221. PMID 17054283.

- ↑ Fuller, SJ; Tan, RS; Martins, RN (September 2007). "Androgens in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease in aging men and possible therapeutic interventions". Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 12 (2): 129–42. PMID 17917157.

- ↑ Thijs L, Fagard R, Forette F, Nawrot T, Staessen JA (October 2003). "Are low dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate levels predictive for cardiovascular diseases? A review of prospective and retrospective studies". Acta Cardiol. 58 (5): 403–10. doi:10.2143/AC.58.5.2005304. PMID 14609305.

- ↑ Crosbie, D; Black, C; McIntyre, L; Royle, PL; Thomas, S (Oct 17, 2007). Crosbie, David, ed. "Dehydroepiandrosterone for systemic lupus erythematosus". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (4): CD005114. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005114.pub2. PMID 17943841.

- ↑ Corona, G; Rastrelli, G; Giagulli, VA; Sila, A; Sforza, A; Forti, G; Mannucci, E; Maggi, M (2013). "Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation in elderly men: a meta-analysis study of placebo-controlled trials". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98: 3615–26. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1358. PMID 23824417.

- 1 2 3 4 Medscape (2010). "DHEA Oral". Drug Reference. WebMD LLC. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ Chang DM, Lan JL, Lin HY, Luo SF (2002). "Dehydroepiandrosterone treatment of women with mild-to-moderate systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Arthritis Rheum. 46 (11): 2924–27. doi:10.1002/art.10615. PMID 12428233.

- ↑ Rabkin JG, McElhiney MC, Rabkin R, McGrath PJ, Ferrando SJ (2006). "Placebo-controlled trial of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) for treatment of nonmajor depression in patients with HIV/AIDS". Am J Psychiatry. 163 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.59. PMID 16390890.

- ↑ Brooke AM, Kalingag LA, Miraki-Moud F, Camacho-Hübner C, Maher KT, Walker DM, Hinson JP, Monson JP (2006). "Dehydroepiandrosterone improves psychological well-being in male and female hypopituitary patients on maintenance growth hormone replacement". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 91 (10): 3773–79. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0316. PMID 16849414.

- ↑ Villareal DT, Holloszy JO (2006). "DHEA enhances effects of weight training on muscle mass and strength in elderly women and men". Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 291 (5): E1003–08. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00100.2006.

- ↑ Medline Plus. "DHEA". Drugs and Supplements Information. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ "DHEA: Side effects and safety". WebMD. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ↑ Häggström, Mikael; Richfield, David (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005. ISSN 2002-4436.

- ↑ Harper's illustrated Biochemistry, 27th edition, Ch.41 "The Diversity of the Endocrine system"

- 1 2 3 4 Chen F, Knecht K, Birzin E, et al. (November 2005). "Direct agonist/antagonist functions of dehydroepiandrosterone". Endocrinology. 146 (11): 4568–76. doi:10.1210/en.2005-0368. PMID 15994348.

- ↑ Gao W, Bohl CE, Dalton JT (September 2005). "Chemistry and structural biology of androgen receptor". Chemical Reviews. 105 (9): 3352–70. doi:10.1021/cr020456u. PMC 2096617

. PMID 16159155.

. PMID 16159155. - ↑ Lindschau C, Kirsch T, Klinge U, Kolkhof P, Peters I, Fiebeler A (September 2011). "Dehydroepiandrosterone-induced phosphorylation and translocation of FoxO1 depend on the mineralocorticoid receptor". Hypertension. 58 (3): 471–78. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171280. PMID 21747041.

- ↑ Kalimi M, Shafagoj Y, Loria R, Padgett D, Regelson W (February 1994). "Anti-glucocorticoid effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 131 (2): 99–104. doi:10.1007/BF00925945. PMID 8035785.

- ↑ Ora Hirsch Pescovitz; Erica A. Eugster (2004). Pediatric Endocrinology: Mechanisms, Manifestations, and Management. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 362–. ISBN 978-0-7817-4059-3.

- ↑ Fima Lifshitz (26 December 2006). Pediatric Endocrinology: Growth, Adrenal, Sexual, Thyroid, Calcium, and Fluid Balance Disorders. CRC Press. pp. 289–. ISBN 978-1-4200-4272-6.

- ↑ Sudha Salhan (1 August 2011). Textbook of Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-93-5025-369-4.

- ↑ J.P. Lavery; J.S. Sanfilippo (6 December 2012). Pediatric and Adolescent Obstetrics and Gynecology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-1-4612-5064-7.

- ↑ Robert L. Nussbaum; Roderick R. McInnes; Huntington F Willard (28 April 2015). Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-323-39206-8.

- ↑ Marcus E Setchell; C. N. Hudson (4 April 2013). Shaw's Textbook of Operative Gynaecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 129–. ISBN 81-312-3481-9.

- ↑ Bruno Bissonnette; Bernard Dalens (20 July 2006). Syndromes: Rapid Recognition and Perioperative Implications. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-07-135455-4.

- ↑ Abraham Weizman (1 February 2008). Neuroactive Steroids in Brain Function, Behavior and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Novel Strategies for Research and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 241–. ISBN 978-1-4020-6854-6.

- ↑ Achille G. Gravanis; Synthia H. Mellon (24 June 2011). Hormones in Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection, and Neurogenesis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 349–. ISBN 978-3-527-63397-5.

- ↑ Sex difference in the human brain, their underpinnings and implications. Elsevier. 3 December 2010. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-0-444-53631-0.

- ↑ Banaszewska B, Spaczyński RZ, Pelesz M, Pawelczyk L (2003). "Incidence of elevated LH/FSH ratioin polycystic ovary syndrome women with normo- and hyperinsulinemia". Annales Academiae Medicae Bialostocensis. 48.

- ↑ Filaire, E; Duché, P; Lac, G (1998). "Effects of amount of training on the saliva concentrations of cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone and on the dehydroepiandrosterone: Cortisol concentration ratio in women over 16 weeks of training". Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 78 (5): 466–71. doi:10.1007/s004210050447. PMID 9809849.

- ↑ Copeland, J. L.; Consitt, L. A.; Tremblay, M. S. (2002). "Hormonal Responses to Endurance and Resistance Exercise in Females Aged 19–69 Years". J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 57 (4): B158–65. doi:10.1093/gerona/57.4.B158.

- ↑ Mattison, Julie A.; Lane, Mark A.; Roth, George S.; Ingram, Donald K. (2003). "Calorie restriction in rhesus monkeys". Experimental Gerontology. 38 (1–2): 35–46. doi:10.1016/S0531-5565(02)00146-8. PMID 12543259..

- ↑ Roberts, E. (1999). "The importance of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in the blood of primates: a longer and healthier life?". Biochemical Pharmacology. 57 (4): 329–46. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00246-9. PMID 9933021..

- ↑ "Drug Scheduling Actions – 2005". Drug Enforcement Administration.

- ↑ Health Canada, DHEA listing in the Ingredient Database

- ↑ Therapeutic Goods Administration, Personal Importation Scheme

- ↑ World Anti-Doping Agency

- ↑ Memphis Grizzlies' O.J. Mayo gets 10-game drug suspension, ESPN, January 27, 2011.

- ↑ Memphis Grizzlies' O.J. Mayo suspended 10 games for violating NBA anti-drug program

- ↑ "US 400m star LaShawn Merritt fails drug test". BBC Sport. 22 April 2010.

- ↑ Russian Olympic Medal-Winning Swimmer Efimova Fails Doping Test – Report

- ↑ Fabio Maldonado plans to use DHEA for Fedor match, admits use in UFC

- ↑ Calfee, R.; Fadale, P. (March 2006). "Popular ergogenic drugs and supplements in young athletes". Pediatrics. 117 (3): e577–89. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1429. PMID 16510635.

In 2004, a new Steroid Control Act that placed androstenedione under Schedule III of controlled substances effective January 2005 was signed. DHEA was not included in this act and remains an over-the-counter nutritional supplement.

External links

- Information on DHEA from the Mayo Clinic

- DHEA in elderly women and DHEA or testosterone in elderly men, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2006. "Neither DHEA nor low-dose testosterone replacement in elderly people has physiologically relevant beneficial effects on body composition, physical performance, insulin sensitivity, or quality of life."

- DHEA, from the Skeptic's Dictionary

- ChemSub Online: Dehydroepiandrosterone - DHEA