Cultural homogenization

Cultural homogenization is an aspect of cultural globalization,[1] listed as one of its main characteristics,[2] and refers to the reduction in cultural diversity[3] through the popularization and diffusion of a wide array of cultural symbols — not only physical objects but customs, ideas and values.[2] O'Connor defines it as "the process by which local cultures are transformed or absorbed by a dominant outside culture."[4] Cultural homogenization has been called "perhaps the most widely discussed hallmark of global culture.[2] In theory, homogenization could result in the breakdown of cultural barriers and the global assimilation of a single culture.[2]

Cultural homogenization can impact national identity and culture, which would be "eroded by the impact of global cultural industries and multinational media."[5] The term is usually used in the context of Western culture dominating and destroying other cultures.[6] The process of cultural homogenization in the context of the domination of the Western (American), capitalist culture is also known as McDonaldization,[2] coca-colonization,[7]Americanization[8] or Westernization[9] and criticized as a form of cultural imperialism[3] and neo-colonialism.[10][11] This process has been resented by many indigenous cultures.[12] However, while some scholars, critical of this process, stress the dominance of American culture and corporate capitalism in modern cultural homogenization, others note that the process of cultural homogenization is not one-way, and in fact involves a number of cultures exchanging various elements.[2][3] Critics of cultural homogenization theory point out that as different cultures mix, homogenization is less about the spread of a single culture as about the mixture of different cultures, as people become aware of other cultures and adopt their elements.[2][3][10][11] Examples of non-Western culture affecting the West include world music and the popularization of non-Western television (Latin American telenovelas, Japanese anime, Indian Bollywood), religion (Islam, Buddhism), food, and clothing in the West, though in most cases insignificant in comparison to the Western influence in other countries.[3][11][13] The process of adoption of elements of global culture to local cultures is known as glocalization[3][5] or cultural heterogenization.[14]

Some scholars like Arjun Appadurai note that "the central problem of today's global interaction [is] the tension between cultural homogenization and cultural heterogenization."[7]

Perspectives

The debate regarding the concept of cultural homogenization consists of two separate questions:

- whether homogenization is occurring or not

- whether it is good or not.

John Tomlinson says, "It is one thing to say that cultural diversity is being destroyed, quite another to lament the fact."[15]

Tomlinson argues that globalization leads to homogenization.[15] He comments on Cees Hamelink, "Hamelink is right to identify cultural synchronization as an unprecedented feature of global modernity."[15] However, unlike Hamelink, he believes in the idea that homogenization is not a bad thing in itself and that benefits of homogenization may outweigh the goods of cultural diversity.[15]

Appadurai, acknowledging the concept of homogenization, still provides an alternative argument of indigenization. He says that " the homogenization argument subspeciates into either an argument about Americanization or an argument about commoditization.... What these arguments fail to consider is that at least as rapidly as forces from various metropolises are brought into new societies, they tend to become indigenized."

Although there is more to be explored on the dynamics of indigenization, examples such as Indonesianization in Irian Jaya and Indianization in Sri Lanka show the possibility of alternatives to Americanization.[16]

Generally homogenization is viewed negatively, as it leads to the "reduction in cultural diversity."[3] However, some scholars have a positive view on homogenization, especially in the area of education.[17] They say that it "produces consistent norms of behavior across a set of modern institutions, thus tying institutions such as the modern nation state and formal education together in a tight political sphere."[17]

Teaching universal values such as rationality by mass schooling is a part of the positive benefits that can be generated from homogenization.[17]

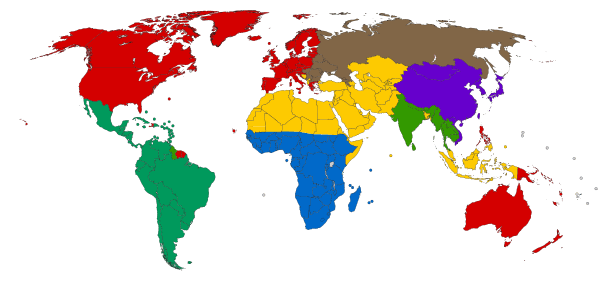

Maps

See also

- American hegemony

- Criticism of Walmart

- Cultural uniformity

- Globalism

- Globalization

- Linguistic imperialism

References

- ↑ Justin Ervin; Zachary Alden Smith (1 August 2008). Globalization: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-59884-073-5. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Justin Jennings (8 November 2010). Globalizations and the Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-521-76077-5. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chris Barker (17 January 2008). Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice. SAGE. pp. 159–162. ISBN 978-1-4129-2416-0. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ David E. O'Connor (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia Of The Global Economy A Guide For Students And Researchers. Academic Foundation. pp. 391–. ISBN 978-81-7188-547-3. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 Mark Kirby (1 May 2000). Sociology in Perspective. Heinemann. pp. 407–408. ISBN 978-0-435-33160-3. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Arthur Asa Berger (21 March 2000). Media and Communication Research: An Introduction to Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. SAGE. pp. 271–. ISBN 978-0-7619-1853-0. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 George Ritzer (15 April 2008). The Blackwell Companion to Globalization. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-470-76642-2. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Ilan Alon (2006). Service Franchising: A Global Perspective. Springer. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-387-28256-5. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Paul Hopper (19 December 2007). Understanding Cultural Globalization. Polity. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7456-3558-3. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 Katie Willis (11 January 2013). Theories and Practices of Development. Taylor & Francis. pp. 193–. ISBN 978-0-415-30052-0. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 Cheris Kramarae; Dale Spender (2000). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women: Global Women's Issues and Knowledge. Taylor & Francis. pp. 933–. ISBN 978-0-415-92088-9. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ David E. O'Connor (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia Of The Global Economy A Guide For Students And Researchers. Academic Foundation. p. 176. ISBN 978-81-7188-547-3. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Mie Hiramoto (9 May 2012). Media Intertextualities. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-272-0256-7. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ Peter Clarke (6 November 2008). The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Oxford Handbooks Online. pp. 492–. ISBN 978-0-19-927979-1. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 John Tomlinson. Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction. Continuum. pp. 45–50, 108–13.

- ↑ Arjun Appadurai. Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy in Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 27–30, 32–43.

- 1 2 3 David P. Baker and Gerald K. LeTendre. National Differences, Global Similarities: World Culture and the Future of Schooling. Stanford University Press. pp. 1–4, 6–10, 12.