Lymphedema

| Lymphedema | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | lymphoedema, lymphatic obstruction |

| |

| Lymphedema on a 67 year old female | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| ICD-10 | I89.0, I97.2, Q82.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 457.0, 457.1, 757.0 |

| OMIM | 153100 |

| DiseasesDB | 7679 |

| eMedicine | article/1087313 |

| MeSH | D008209 |

Lymphedema is a condition of localized fluid retention and tissue swelling caused by a compromised lymphatic system, which normally returns interstitial fluid to the thoracic duct, then the bloodstream. The condition can be inherited or can be caused by a birth defect, though it is frequently caused by cancer treatments and by parasitic infections. Though incurable and progressive, a number of treatments can ameliorate symptoms. Tissues with lymphedema are at high risk of infection.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may include a feeling of heaviness or fullness, edema, and (occasionally) aching pain in the affected area. In advanced lymphedema, there may be the presence of skin changes such as discoloration, verrucous (wart-like) hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis; and eventually deformity (elephantiasis).

Lymphedema should not be confused with edema arising from venous insufficiency, which is not lymphedema. However, untreated venous insufficiency can progress into a combined venous/lymphatic disorder which is treated the same way as lymphedema.

Presented here is an extreme case of severe unilateral hereditary lymphedema which had been present for 25 years without treatment:

.jpg) Comparison of normal and swollen limb

Comparison of normal and swollen limb.jpg) Size of swollen foot, toes underneath

Size of swollen foot, toes underneath.jpg) Another view of lymphedemic foot

Another view of lymphedemic foot.jpg) Foot and leg (held vertically)

Foot and leg (held vertically)

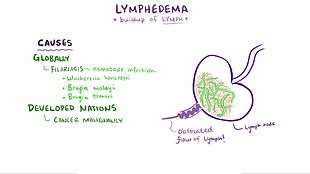

Causes

Lymphedema affects approximately 140 million people worldwide.[1]

Lymphedema may be inherited (primary) or caused by injury to the lymphatic vessels (secondary). It is most frequently seen after lymph node dissection, surgery and/or radiation therapy, in which damage to the lymphatic system is caused during the treatment of cancer, most notably breast cancer. In many patients with cancer, this condition does not develop until months or even years after therapy has concluded. Lymphedema may also be associated with accidents or certain diseases or problems that may inhibit the lymphatic system from functioning properly. In tropical areas of the world, a common cause of secondary lymphedema is filariasis, a parasitic infection. It can also be caused by a compromising of the lymphatic system resulting from cellulitis.

While the exact cause of primary lymphedema is still unknown, it generally occurs due to poorly developed or missing lymph nodes and/or channels in the body. Lymphedema may be present at birth, develop at the onset of puberty (praecox), or not become apparent for many years into adulthood (tarda). In men, lower-limb primary lymphedema is most common, occurring in one or both legs. Some cases of lymphedema may be associated with other vascular abnormalities.

Secondary lymphedema affects both men and women. In women, it is most prevalent in the upper limbs after breast cancer surgery, in particular after axillary lymph node dissection,[2] occurring in the arm on the side of the body in which the surgery is performed. In Western countries, secondary lymphedema is most commonly due to cancer treatment.[1] Between 38 and 89% of breast cancer patients suffer from lymphedema due to axillary lymph node dissection and/or radiation.[1][3][4] Unilateral lymphedema occurs in up to 41% of patients after gynecologic cancer.[1][5] For men, a 5-66% incidence of lymphedema has been reported in patients treated with incidence depending on whether staging or radical removal of lymph glands was done in addition to radiotherapy.[1][6][7]

Head and neck lymphedema can be caused by surgery or radiation therapy for tongue or throat cancer. It may also occur in the lower limbs or groin after surgery for colon, ovarian or uterine cancer, in which removal of lymph nodes or radiation therapy is required. Surgery or treatment for prostate, colon and testicular cancers may result in secondary lymphedema, particularly when lymph nodes have been removed or damaged.

The onset of secondary lymphedema in patients who have had cancer surgery has also been linked to aircraft flight (likely due to decreased cabin pressure or relative immobility). For cancer survivors, therefore, wearing a prescribed and properly fitted compression garment may help decrease swelling during air travel.

Some cases of lower-limb lymphedema have been associated with the use of tamoxifen, due to the blood clots and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that can be caused by this medication. Resolution of the blood clots or DVT is needed before lymphedema treatment can be initiated.

Congenital lymphedema

Congenital lymphedema is swelling that results from abnormalities in the lymphatic system that are present from birth. Swelling may be present in a single affected limb, several limbs, genitalia, or the face. It is sometimes diagnosed prenatally by a nuchal scan or post-natally by lymphoscintigraphy. A hereditary form of congenital lymphedema is called Milroy's disease and is caused by mutations in the VEGFR3 gene.[8] Congenital lymphedema is frequently syndromic and is associated with Turner syndrome, lymphedema–distichiasis syndrome, yellow nail syndrome, and Klippel–Trénaunay–Weber syndrome.[9] In some cases, the condition can sometimes be associated with congenital heart defect, among other things.[10]

Physiology

Lymph is formed from the fluid that filters out of the blood circulation to nourish cells. This fluid returns through venous capillaries to the blood circulation through the force of osmosis in the venous blood; however, a portion of the fluid that contains proteins, cellular debris, bacteria, etc. must return through the lymphatic collection system to maintain tissue fluid balance. The collection of this prelymph fluid is carried out by the initial lymph collectors that are blind-ended epithelial-lined vessels with fenestrated openings that allow fluids and particles as large as cells to enter. Once inside the lumen of the lymphatic vessels, the fluid is guided along increasingly larger vessels, first with rudimentary valves to prevent backflow, which later develop into complete valves similar to the venous valve. Once the lymph enters the fully valved lymphatic vessels, it is pumped by a rhythmic peristaltic-like action by smooth muscle cells within the lymphatic vessel walls. This peristaltic action is the primary driving force, moving lymph within its vessel walls. The regulation of the frequency and power of contraction is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system. Lymph movement can be influenced by the pressure of nearby muscle contraction, arterial pulse pressure and the vacuum created in the chest cavity during respiration, but these passive forces contribute only a minor percentage of lymph transport. The fluids collected are pumped into continually larger vessels and through lymph nodes, which remove debris and police the fluid for dangerous microbes. The lymph ends its journey in the thoracic duct or right lymphatic duct, which drain into the blood circulation.

Diagnosis

Assessment of the lower extremities begins with a visual inspection. Color, presence of hair, visible veins, size and any sores or ulcerations are noted. Lack of hair may indicate an arterial circulation problem.[11] Given swelling, the calf circumference is measured for reference as time continues. Elevating the legs may reduce or eliminate the swelling. Palpation of the ankle can determine the degree of swelling. Assessment includes a check of the popliteal, femoral, posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses. The inguinal nodes may be enlarged. Enlargement of the nodes lasting more than three weeks may indicate infection or some other disease process requiring further medical attention.[11]

Diagnosis or early detection of lymphedema is difficult. The first signs may be subjective observations such as "my arm feels heavy" or "I have difficulty these days getting rings on and off my fingers". These may be symptomatic of early stage of lymphedema where accumulation of lymph is mild and not detectable by changes in volume or circumference. As lymphedema develops further, definitive diagnosis is commonly based upon an objective measurement of differences between the affected or at-risk limb at the opposite unaffected limb, e.g. in volume or circumference. No generally accepted criterion is definitively diagnostic, although a volume difference of 200 ml between limbs or a 4-cm difference (at a single measurement site or set intervals along the limb) is often used. Bioimpedance measurement (which measures the amount of fluid in a limb) offers greater sensitivity than existing methods.[12]

Chronic venous stasis changes can mimic early lymphedema, but the changes in venous stasis are more often bilateral and symmetric. Lipedema can also mimic lymphedema, however lipedema characteristically spares the feet beginning abruptly at the medial malleoli (ankle level). Lipedema is common in overweight women. As a part of the initial work-up before diagnosing lymphedema, it may be necessary to exclude other potential causes of lower extremity swelling such as renal failure, hypoalbuminemia, congestive heart-failure, protein-losing nephropathy, pulmonary hypertension, obesity, pregnancy and drug-induced edema.[13]

Stages

Whether primary or secondary, lymphedema develops in stages, from mild to severe. Methods of staging are numerous and inconsistent across the globe. Lymphedema staging systems range from three to eight stages.

Staging system of lymphedema to improve diagnosis and outcome

One staging system was endorsed by the American Society of Lymphology.[14] This system provides a four-stage technique that can be employed by clinical and laboratory assessments to more accurately diagnose and prescribe therapy and obtain measurable outcomes. Symptom descriptors and clinical presentation must be established at the assessment by the physician to prescribe interventions, monitor efficacy and support medical necessity. Additional assessments, such as bioimpedance, MRI or CT, build on a clinical assessment (physical evaluation).

The most common method of staging was defined by the Fifth WHO Expert Committee on Filariasis:[15][16]

- Stage 0 (latent): The lymphatic vessels have sustained some damage that is not yet apparent. Transport capacity is sufficient for the amount of lymph being removed. Lymphedema is not present.

- Stage 1 (spontaneously reversible): Tissue is still at the pitting stage: when pressed by the fingertips, the affected area indents and reverses with elevation. Usually upon waking in the morning, the limb or affected area is normal or almost normal in size.

- Stage 2 (spontaneously irreversible): The tissue now has a spongy consistency and is considered non-pitting: when pressed by the fingertips, the affected area bounces back without indentation. Fibrosis found in stage 2 lymphedema marks the beginning of the hardening of the limbs and increasing size.

- Stage 3 (lymphostatic elephantiasis): At this stage, the swelling is irreversible and usually the limb(s) or affected area is noticeably large. The tissue is hard (fibrotic) and unresponsive; some patients consider undergoing reconstructive surgery, called "debulking". This remains controversial, however, since the risks may outweigh the benefits and the further damage done to the lymphatic system may in fact make the lymphedema worse.

Grades

Lymphedema can also be categorized by its severity (usually referenced to a healthy extremity):

- Grade 1 (mild edema): Involves the distal parts such as a forearm and hand or a lower leg and foot. The difference in circumference is less than 4 cm and other tissue changes are not yet present.

- Grade 2 (moderate edema): Involves an entire limb or corresponding quadrant of the trunk. Difference in circumference is 4–6 cm. Tissue changes, such as pitting, are apparent. The patient may experience erysipelas.

- Grade 3a (severe edema): Lymphedema is present in one limb and its associated trunk quadrant. Circumferential difference is greater than 6 centimeters. Significant skin alterations, such as cornification or keratosis, cysts and/or fistulae, are present. Additionally, the patient may experience repeated attacks of erysipelas.

- Grade 3b (massive edema): The same symptoms as grade 3a, except that two or more extremities are affected.

- Grade 4 (gigantic edema): Also known as elephantiasis, in this stage of lymphedema, the affected extremities are huge, due to almost complete blockage of the lymph channels. Elephantiasis may also affect the head and face.

Treatment

Treatment varies depending on edema severity and the degree of fibrosis. Most people with lymphedema follow a daily regimen of treatment. The most common treatments are a combination of manual compression lymphatic massage, compression garments or bandaging. Complex decongestive physiotherapy is an empiric system of lymphatic massage, skin care and compressive garments. Although a combination treatment program may be ideal, any of the treatments can be done individually.

Complete decongestive therapy

CDT is a primary tool in lymphedema management. It consists of manual manipulation of the lymphatic ducts,[17] short-stretch compression bandaging, therapeutic exercise and skin care. The technique was pioneered by Emil Vodder in the 1930s for the treatment of chronic sinusitis and other immune disorders. Initially, CDT involves frequent visits to a therapist. Once the lymphedema is reduced, increased patient participation is required for ongoing care, along with the use of elastic compression garments and nonelastic directional flow foam garments.

Manual manipulation of the lymphatic ducts (manual lymphatic drainage or MLD) consists of gentle, rhythmic massage to stimulate lymph flow and its return to the blood circulation system. The treatment is gentle. A typical session involves drainage of the neck, trunk and involved extremity (in that order), lasting approximately 40 to 60 minutes. CDT is generally effective on nonfibrotic lymphedema and less effective on more fibrotic legs, although it helps break up fibrotic tissue.

Compression

Garments

Elastic compression garments are worn on the affected limb following complete decongestive therapy to maintain edema reduction. Inelastic garments provide containment and reduction.

Bandaging

Compression bandaging, also called wrapping, is the application of layers of padding and short-stretch bandages to the involved areas. Short-stretch bandages are preferred over long-stretch bandages (such as those normally used to treat sprains), as the long-stretch bandages cannot produce the proper therapeutic tension necessary to safely reduce lymphedema and may in fact end up producing a tourniquet effect. During activity, whether exercise or daily activities, the short-stretch bandages enhance the pumping action of the lymph vessels by providing increased resistance. This encourages lymphatic flow and helps to soften fluid-swollen areas.

A 2002 study showed patients receiving the combined modalities of manual lymph drainage (MLD) with complete decongestive therapy (CDT) and pneumatic pumping had a greater overall reduction in limb volume than patients receiving only MLD/CDT.[18]

Intermittent pneumatic compression therapy

Intermittent pneumatic compression therapy (IPC) utilizes a multi-chambered pneumatic sleeve with overlapping cells to promote movement of lymph fluid. Pump therapy should be used in addition to other treatments such as compression bandaging and manual lymph drainage. In some cases, pump therapy helps soften fibrotic tissue and therefore potentially enable more efficient lymphatic drainage. However, reports link pump therapy to increased incidence of edema proximal to the affected limb, such as genital edema arising after pump therapy in the lower limb.[19] IPC should be used in combination with complete decongestive therapy.[18]

Exercise

Most studies investigating the effects exercise in patients with lymphedema or at risk of developing lymphedema examined patients with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. In these studies, resistance training did not increase swelling in patients with pre-existing lymphedema and decreases edema in some patients, in addition to other potential beneficial effects on cardiovascular health.[20][21][22][23] Moreover, resistance training and other forms of exercise were not associated with an increased risk of developing lymphedema in patients who previously received breast cancer-related treatment. Compression garments should be worn during exercise (with the possible exception of swimming in some patients).[24] Patients who have or risk lymphedema should consult their physician or certified lymphedema therapist before beginning an exercise regimen. Resistance training is not recommended in the immediate post-operative period in patients who have undergone axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer.

Few studies examine the effects of exercise in primary lymphedema or in secondary lymphedema that is not related to breast cancer treatment.

Surgery

Several surgical procedures provide long-term solutions for patients who suffer from lymphedema. Prior to surgery, patients typically are treated by a physical or occupational therapist, trained in providing lymphedema treatment for initial conservative treatment of their lymphedema. CDT, MLD and compression bandaging are all helpful components of conservative lymphedema treatment.[25]

Vascularized lymph node transfer

Vascularized lymph node transfers (VLNT) can be an effective treatment of the arm and upper extremity. Lymph nodes are harvested from the groin area with their supporting artery and vein and moved to the axilla (armpit). Microsurgery techniques connect the artery and vein to blood vessels in the axilla to provide support to the lymph nodes while they develop their own blood supply over the first few weeks after surgery.

The newly transferred lymph nodes then serve as a conduit or filter to remove the excess lymphatic fluid from the arm and return it to the body's natural circulation.

This technique of lymph node transfer usually is performed together with a DIEP flap breast reconstruction. This allows for both the simultaneous treatment of the arm lymphedema and the creation of a breast in one surgery. The lymph node transfer removes the excess lymphatic fluid to return form and function to the arm. In selected cases, the lymph nodes may be transferred as a group with their supporting artery and vein, but without the associated abdominal tissue for breast reconstruction.

Lymph node transfers are most effective in patients whose extremity circumference reduces significantly with compression wrapping, indicating most of the edema is fluid.

VLNT significantly improves the fluid component of lymphedema and decrease the amount of lymphedema therapy and compression garment use required.[26]

Lymphaticovenous anastomosis

Lymphaticovenous anastomosis (LVA) uses supermicrosurgery to connect the affected lymphatic channels directly to tiny veins located nearby. The lymphatics are tiny, typically 0.1 mm to 0.8 mm in diameter. The procedure requires the use of specialized techniques with superfine surgical suture and an adapted, high-power microscope.

LVA can be an effective and long-term solution for extremity lymphedema and many patients have results that range from a moderate improvement to an almost complete resolution. LVA is most effective early in the course of the disease in patients whose extremity circumference reduces significantly with compression wrapping, indicating most of the edema is fluid. Patients who do not respond to compression are less likely to fare well with LVA, as a greater amount of their increased extremity volume consists of fibrotic tissue, protein or fat. Multiple studies showed LVAs to be effective.[26][27][28]

Lymphaticovenous anastomosis was introduced by B. M. O'Brien and colleagues for the treatment of obstructive lymphedema in the extremities.[29] In 2003, supermicrosurgery pioneer Isao Koshima and colleagues improved the surgery with supermicrosurgical techniques and established the new standard in reconstructive microsurgery.[29] Studies involving long-term follow-up after LVA for lymphedema indicated patients showed remarkable improvement compared to conservative treatment using continuous elastic stocking and occasional pumping.[29]

Clinical studies involving LVA indicate immediate and long-term results showed significant reductions in volume and improvement in systems that appear to be long-lasting.[26][27][30] A 2006 study comparing two groups of breast cancer patients at high risk for lymphedema in whom LVA was used to prevent the onset of clinically evident lymphedema. Results showed a statistically significant reduction in the number of patients who went on to develop clinically significant lymphedema.[30] Other studies showed LVA surgeries reduce the severity of lymphedema in breast cancer patients.[31][32] In particular, a clinical study of 1,000 cases of lymphedema treated with microsurgery from 1973 to 2006 showed beneficial results.[32] Clinical reports from microsurgeons and physical therapists documented more than 1,500 patients treated with LVA surgery over a span of 30 years showing significant improvement and effectiveness.[28]

Indocyanine green fluoroscopy is a safe, minimally invasive and useful tool for surgical evaluation.[33] Microsurgeons use indocyanine green lymphography to assist in LVA surgeries.[34]

Suction assisted lipectomy

People whose limbs no longer adequately respond to compression therapy may be candidates for suction assisted lipectomy (SAL). This procedure has been called liposuction for lymphedema and is specifically adapted to treat this advanced condition. SAL employs a different operative technique and requires significant therapy and compression garment care that must be administered by a therapist experienced in the technique.

This procedure was pioneered by Hakan Brorson in 1987.[1] Well-controlled clinical trials conducted from 1993 to 2014 showed SAL, combined with controlled compression therapy (CCT), to be an effective lymphedema treatment without recurrence.[1][26][27][35][36][37][38][39] Long-term followup (11–13 years) of patients with lymphedema showed no recurrence of swelling.[1] Lymphatic liposuction combined with controlled compression therapy was more effective than controlled compression therapy alone.[40][41]

SAL has been refined in recent years by using vibrating cannulae that are finer and more effective than previous equipment.[1] In addition, the introduction of the tourniquet and tumescent technique led to minimized blood loss.[1][42]

SAL uses specialized techniques that differ from conventional liposuction procedures and requires specific training.

Lymphatic vessel grafting

With advanced microsurgical techniques, lymph vessels can be used as grafts. A locally interrupted or obstructed lymphatic pathway, mostly after resection of lymph nodes, can be reconstructed via a bypass using lymphatic vessels. These vessels are specialized to drain lymph by active pumping forces. These grafts are connected with main lymphatic collectors in front and behind the obstruction. The technique is mostly used in arm edemas after treatment of breast cancer and in unilateral edemas of lower extremities after resection of lymph nodes and radiation. The procedure is less widely used than the other surgical procedures, mainly in Germany. The method was developed in 1980 by Ruediger Baumeister.[43]

The method is proven effective.[44] Follow-up studies showed significant volume reduction of the extremities even 10 years after surgery.[45] The patients, who had been previously treated with both MLD and compression therapy, gained significant improvement in quality of life after being treated with lymphatic vessel grafting.[46] Lymphoscintigraphic investigations showed a lasting enhancement of lymphatic transport after grafting.[47]

The patency of lymphatic grafts was demonstrated after more than 12 years, using indirect lymphography and MRI lymphography.

Low level laser therapy

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of lymphedema in November 2006.[48]

According to the US National Cancer Institute,

Studies suggest that low-level laser therapy may be effective in reducing lymphedema in a clinically meaningful way for some women. Two cycles of laser treatment were found to be effective in reducing the volume of the affected arm, extracellular fluid, and tissue hardness in approximately one-third of patients with postmastectomy lymphedema at 3 months posttreatment. Suggested rationales for laser therapy include a potential decrease in fibrosis, stimulation of macrophages and the immune system, and a possible role in encouraging lymphangiogenesis.[49][50]

Prevention and disease regression in breast cancer

In 2008, an NIH study revealed early diagnosis of lymphedema in breast cancer patients ("stage 0") associated with an early intervention, a compression sleeve and gauntlet for one month, led to a return to preoperative baseline status. In a five-year followup, patients remained at their preoperative baseline, suggesting preclinical detection of lymphedema can halt if not reverse its progression.

Complications

When the lymphatic impairment becomes so great that the lymph fluid exceeds the lymphatic system's ability to transport it, an abnormal amount of protein-rich fluid collects in the tissues. Left untreated, this stagnant, protein-rich fluid causes tissue channels to increase in size and number, reducing oxygen availability. This interferes with wound healing and provides a rich culture medium for bacterial growth that can result in infections: cellulitis, lymphangitis, lymphadenitis and in severe cases, skin ulcers. It is vital for lymphedema patients to be aware of the symptoms of infection and to seek immediate treatment, since recurrent infections or cellulitis, in addition to their inherent danger, further damage the lymphatic system and set up a vicious circle.

In rare cases, lymphedema can lead to a form of cancer called lymphangiosarcoma, although the mechanism of carcinogenesis is not understood. Lymphedema-associated lymphangiosarcoma is called Stewart-Treves syndrome. Lymphangiosarcoma most frequently occurs in cases of long-standing lymphedema. The incidence of angiosarcoma is estimated to be 0.45% in patients living 5 years after radical mastectomy.[51][52] Lymphedema is also associated with a low grade form of cancer called retiform hemangioendothelioma (a low grade angiosarcoma).[53]

Since lymphedema is disfiguring, causing difficulties in daily living and can lead to lifestyle becoming severely limited, it may also result in psychological distress.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Svensson B, Svensson H (June 2008). "Controlled compression and liposuction treatment for lower extremity lymphedema". Lymphology. 41 (2): 52–63. PMID 18720912.

- ↑ Jeannie Burt; Gwen White (1 January 2005). Lymphedema: A Breast Cancer Patient's Guide to Prevention and Healing. Hunter House. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-89793-458-9.

- ↑ Kissin MW, Querci della Rovere G, Easton D, Westbury G (July 1986). "Risk of lymphoedema following the treatment of breast cancer". Br J Surg. 73 (7): 580–4. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800730723. PMID 3730795.

- ↑ Segerström K, Bjerle P, Graffman S, Nyström A (1992). "Factors that influence the incidence of brachial oedema after treatment of breast cancer". Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 26 (2): 223–7. doi:10.3109/02844319209016016. PMID 1411352.

- ↑ Werngren-Elgström M, Lidman D (December 1994). "Lymphoedema of the lower extremities after surgery and radiotherapy for cancer of the cervix". Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 28 (4): 289–93. doi:10.3109/02844319409022014. PMID 7899840.

- ↑ Pilepich MV, Asbell SO, Mulholland GS, Pajak T (1984). "Surgical staging in carcinoma of the prostate: the RTOG experience. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group". Prostate. 5 (5): 471–6. doi:10.1002/pros.2990050502. PMID 6483687.

- ↑ Pilepich MV, Krall J, George FW, Asbell SO, Plenk HD, Johnson RJ, Stetz J, Zinninger M, Walz BJ (1994). "Treatment-related morbidity in Phase III RTOG studies of extended-field irradiation for carcinoma of the prostate". Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 10 (10): 1861–7. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(84)90263-3. PMID 6386761.

- ↑ Liem TK, Moneta GL. Chapter 24. Venous and Lymphatic Disease. In: Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Matthews JB, Pollock RE, eds. Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=5014541.

- ↑ Boon LM, Vikkula M. Chapter 172. Vascular Malformations. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Dallas NA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- ↑ "Relationship Between Nuchal Translucency Thickness and Prevalence of Major Cardiac Defects in Fetuses With Normal Karyotype", by Atzei, A; Gajewska, K; Huggon, I C.; Allan, L; Nicolaides, K H. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. January 2006. Volume 61, Issue 1, pages 8-10.

- 1 2 Jarvis, C. (2004). Physical Examination and Health Assessment (5th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 530–553. ISBN 1-4160-5188-0.

- ↑ Ward LC (2006). "Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis: Proven Utility in Lymphedema Risk Assessment and Therapeutic Monitoring". Lymphatic Research and Biology. 4 (1): 51–6. doi:10.1089/lrb.2006.4.51. PMID 16569209.

- ↑ Burkhart CN, Adigun C, Burton CS. Chapter 174. Cutaneous Changes in Peripheral Venous and Lymphatic Insufficiency. In: Wolff K, ed. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=56081150. Accessed November 3, 2013.

- ↑ Lawrence L Tretbar; Cheryl L. Morgan; Byung-Boong Lee; Benoit Blondeau; Simon J. Simonian (2007). Lymphedema: Diagnosis and Treatment. Springer. ISBN 1-84628-548-8.

- ↑ "Lymphatic filariasis: The disease and its control. Fifth report of the WHO Expert Committee on Filariasis". World Health Organization technical report series. 821: 1–71. 1992. PMID 1441569.

- ↑ "Treatment and Prevention of Problems Associated with Lymphatic Filariasis" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ http://www.lymphnet.org/pdfDocs/nlntreatment.pdf

- 1 2 Szuba A, Achalu R, Rockson SG (2002). "Decongestive lymphatic therapy for patients with breast carcinoma-associated lymphedema". Cancer. 95 (11): 2260–7. doi:10.1002/cncr.10976. PMID 12436430.

- ↑ Boris M, Weindorf S, Lasinski BB (Mar 1998). "The risk of genital edema after external pump compression for lower limb lymphedema". Lymphology. 31 (1): 15–20. PMID 9561507.

- ↑ Markes M, Brockow T, Resch KL (2006). "Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (4): CD005001. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005001.pub2. PMID 17054230.

- ↑ McKenzie DC, Kalda AL (2003). "Effect of upper extremity exercise on secondary lymphedema in breast cancer patients: A pilot study". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 21 (3): 463–6. doi:10.1200/jco.2003.04.069. PMID 12560436.

- ↑ Ahmed RL, Thomas W, Yee D, Schmitz KH (2006). "Randomized controlled trial of weight training and lymphedema in breast cancer survivors". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (18): 2765–72. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6749. PMID 16702582.

- ↑ Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, Cheville A, Smith R, Lewis-Grant L, Bryan CJ, Williams-Smith CT, Greene QP (2009). "Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (7): 664–73. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810118. PMID 19675330.

- ↑ "Position Paper: Exercise | National Lymphedema Network". Lymphnet.org. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ Granzow, Jay W.; Soderberg, Julie M.; Kaji, Amy H.; Dauphine, Christine (2014). "Review of Current Surgical Treatments for Lymphedema". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 21 (4): 1195–1201. doi:10.1245/s10434-014-3518-8. ISSN 1068-9265.

- 1 2 3 4 Granzow, Jay W.; Soderberg, Julie M.; Kaji, Amy H.; Dauphine, Christine (2014). "An Effective System of Surgical Treatment of Lymphedema". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 21 (4): 1189–1194. doi:10.1245/s10434-014-3515-y. ISSN 1068-9265.

- 1 2 3 Granzow JW, Soderberg JM, Dauphine C. A Novel Two-Stage Surgical Approach to Treat Chronic Lymphedema. Breast J. 2014 Jun 19.

- 1 2 Campisi C, Eretta C, Pertile D, Da Rin E, Campisi C, Macciò A, Campisi M, Accogli S, Bellini C, Bonioli E, Boccardo F (2007). "Microsurgery for treatment of peripheral lymphedema: long-term outcome and future perspectives". Microsurgery. 27 (4): 333–8. doi:10.1002/micr.20346. PMID 17477420.

- 1 2 3 Koshima I, Nanba Y, Tsutsui T, Takahashi Y, Itoh S (May 2003). "Long-term follow-up after lymphaticovenular anastomosis for lymphedema in the leg". J Reconstr Microsurg. 19 (4): 209–15. doi:10.1055/s-2003-40575. PMID 12858242.

- 1 2 Campisi C, Davini D, Bellini C, Taddei G, Villa G, Fulcheri E, Zilli A, da Rin E, Eretta C, Boccardo F (2006). "Is there a role for microsurgery in the prevention of arm lymphedema secondary to breast cancer treatment?". Microsurgery. 26 (1): 70–2. doi:10.1002/micr.20215. PMID 16444710.

- ↑ Chang DW (September 2010). "Lymphaticovenular bypass for lymphedema management in breast cancer patients: a prospective study". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 126 (3): 752–8. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e5f6a9. PMID 20811210.

- 1 2 Campisi C, Davini D, Bellini C, Taddei G, Villa G, Fulcheri E, Zilli A, Da Rin E, Eretta C, Boccardo F (2006). "Lymphatic microsurgery for the treatment of lymphedema". Microsurgery. 26 (1): 65–9. doi:10.1002/micr.20214. PMID 16444753.

- ↑ Yamamoto T, Narushima M, Doi K, Oshima A, Ogata F, Mihara M, Koshima I, Mundinger GS (May 2011). "Characteristic indocyanine green lymphography findings in lower extremity lymphedema: the generation of a novel lymphedema severity staging system using dermal backflow patterns". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 127 (5): 1979–86. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820cf5df. PMID 21532424.

- ↑ Ogata F, Narushima M, Mihara M, Azuma R, Morimoto Y, Koshima I (August 2007). "Intraoperative lymphography using indocyanine green dye for near-infrared fluorescence labeling in lymphedema". Ann Plast Surg. 59 (2): 180–4. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000253341.70866.54. PMID 17667413.

- ↑ Brorson, Hakan; Karin Ohlin, OCT, Barbro Svensson, PT, LT (2008). "The Facts About Liposuction As A Treatment For Lymphoedema". Journal of Lymphoedema. 3 (1): 38–47. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Brorson H, Svensson H (June 1997). "Complete reduction of lymphoedema of the arm by liposuction after breast cancer". Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 31 (2): 137–43. doi:10.3109/02844319709085480. PMID 9232698.

- ↑ Brorson H (2000). "Liposuction gives complete reduction of chronic large arm lymphedema after breast cancer". Acta Oncol. 39 (3): 407–20. doi:10.1080/028418600750013195. PMID 10987239.

- ↑ Brorson H (2003). "Liposuction in arm lymphedema treatment" (PDF). Scand J Surg. 92 (4): 287–95. PMID 14758919.

- ↑ Brorson, H.; K. Ohlin; G. Olsson; et al. (2006). "Long term cosmetic and functional results following liposuction for arm lymphedema: An eleven year study". Lymphology. 40 (Supp): 253–255.

- ↑ Brorson H, Svensson H (September 1998). "Liposuction combined with controlled compression therapy reduces arm lymphedema more effectively than controlled compression therapy alone". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 102 (4): 1058–67; discussion 1068. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809020-00022. PMID 9734424.

- ↑ Damstra RJ, Voesten HG, Klinkert P, Brorson H (August 2009). "Circumferential suction-assisted lipectomy for lymphoedema after surgery for breast cancer". Br J Surg. 96 (8): 859–64. doi:10.1002/bjs.6658. PMID 19591161.

- ↑ Wojnikow S, Malm J, Brorson H (2007). "Use of a tourniquet with and without adrenaline reduces blood loss during liposuction for lymphoedema of the arm". Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery / Nordisk Plastikkirurgisk Forening [and] Nordisk Klubb for Handkirurgi. 41 (5): 243–9. doi:10.1080/02844310701546920. PMID 17886128.

- ↑ Baumeister RG, Seifert J, Wiebecke B, Hahn D (May 1981). "Experimental basis and first application of clinical lymph vessel transplantation of secondary lymphedema". World J Surg. 5 (3): 401–7. doi:10.1007/BF01658013. PMID 7293201.

- ↑ Baumeister RG, Siuda S (January 1990). "Treatment of lymphedemas by microsurgical lymphatic grafting: what is proved?". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 85 (1): 64–74; discussion 75–6. doi:10.1097/00006534-199001000-00012. PMID 2293739.

- ↑ Baumeister RG, Frick A (July 2003). "[The microsurgical lymph vessel transplantation]". Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir (in German). 35 (4): 202–9. doi:10.1055/s-2003-42131. PMID 12968216.

- ↑ Springer S, Koller M, Baumeister RG, Frick A (June 2011). "Changes in quality of life of patients with lymphedema after lymphatic vessel transplantation". Lymphology. 44 (2): 65–71. PMID 21949975.

- ↑ Weiss M, Baumeister RG, Hahn K (November 2002). "Post-therapeutic lymphedema: scintigraphy before and after autologous lymph vessel transplantation: 8 years of long-term follow-up". Clin Nucl Med. 27 (11): 788–92. doi:10.1097/01.RLU.0000033613.05410.34. PMID 12394126.

- ↑ dotmed.com December 27, 2006 Low Level Laser FDA Cleared for the Treatment of Lymphedema. (accessed 9 November 09)

- ↑ National Cancer Institute: Low-level laser therapy accessed 9 November 09

- ↑ Carati CJ, Anderson SN, Gannon BJ, Piller NB (2003). "Treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema with low-level laser therapy". Cancer. 98 (6): 1114–22. doi:10.1002/cncr.11641. PMID 12973834.

- ↑ Martin MB, Kon ND, Kawamoto EH, Myers RT, Sterchi JM (1984). "Postmastectomy angiosarcoma". The American surgeon. 50 (10): 541–5. PMID 6541442.

- ↑ Chopra S, Ors F, Bergin D (2007). "MRI of angiosarcoma associated with chronic lymphoedema: Stewart Treves syndrome". British Journal of Radiology. 80 (960): e310–3. doi:10.1259/bjr/19441948. PMID 18065640.

- ↑ Requena L, Sangueza OP (1998). "Cutaneous vascular proliferations. Part III. Malignant neoplasms, other cutaneous neoplasms with significant vascular component, and disorders erroneously considered as vascular neoplasms". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 38 (2): 143–75; quiz 176–8. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70237-3. PMID 9486670.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lymphedema. |