Citole

|

An angel playing a citole in an English stained glass window, c. 1310. | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Plucked string instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification |

321.322-6 (flat-backed) (Chordophone with permanently attached resonator and neck, sounded by a plectrum) |

| Developed | 9th-13th Centuries from the cithara (lyre) and/or other lutes |

| Related instruments | |

|

Bowed Plucked | |

Citole, also spelled Sytole, Cytiole, Gytolle, etc. (probably a French diminutive form of cithara, and not from Latin cista, a box), an archaic musical instrument, and ancestor to the cittern and possibly the modern guitar.[1] It was mentioned in popular poetry, beginning in the 12th Century A.D and largely disappearing in the 15th.[1] Its high period was the 13th and 14th Centuries.[1] It was also included in paintings and sculpture from the 12th through 14th centuries.[2] From the artwork, scholars know that it was generally a four-string instrument, with a "holly-leaf" or "T-shaped" body.

While paintings and sculpture exist, only one instrument has survived the centuries.[2] The sole survivor, associated with Warwick Castle, was made around 1290–1300.[3] It is now preserved in the British Museum's collection.[3] At some point, probably in the sixteenth century, it was converted into a violin-type instrument with a tall bridge, 'f'-holes and angled fingerboard; thus, the instrument's top is not representative of its original appearance. That instrument contributed to a great deal of confusion. It was labeled a violin in the 18th century, a gittern in the 19th century and finally a citole, beginning in the mid 20th century. That confusion is itself illustrative of the confusion about the nature of citoles and gitterns; the instruments had disappeared and scholars in later centuries were confused as to which images and sculpture went with the names found in the poetry and other literature.

Additionally, scholars have translated passages in such a way that literature itself can not always be trusted. One example: a specific reference to the citole may be found in Wycliffe's Bible (1360) in 2 Samuel vi. 5: "Harpis and sitols and tympane". However, the Authorized Version has psaltiries, and the Vulgate lyrae. The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica contributed as well saying that the citole has been supposed to be another name for the psaltery, a box-shaped instrument often seen in the illuminated missals of the Middle Ages, and is also liable to confusion with the gittern[4] Whether the terms overlapped in medieval usage has been the subject of modern controversy. The controversy of citole versus gittern was largely resolved in a 1977 article by Lawrence Wright, called The Medieval Gittern and Citole: A Case of Mistaken Identity.[5]

Characteristics

One of the most prominent features of citoles was a deep neck, so thick that a thumb hole was carved within the neck.[6] This feature gradually receded as the instrument was transformed into the cittern, first becoming larger and then turning into a hook on the back of the neck (a feature of some citterns). Another feature documented is the back which was not curved into a bowl, nor flat like a modern guitar.[6] Instead it "slants upwards from each side to a central ridge extended in the neck."[6] Most citole artwork shows a point at the bottom (often in the shape of a Fleur-de-lis or trefoil, forming a fixed point where the strings could be attached.[6] The pegs were shown as being in the end of the instrument, not in the sides like a violin. The Warwick cithole is not a good example of this because it was was modified; it originally had six end-mounted pegs.[7] The peg holes were covered up during modification but were visible when the instrument was X-rayed.[7]

The overall shape of the instrument varied, but two forms were commonly illustrated, the holly-leaf shaped instruments and the T-shaped instruments.

Holly-leaf citoles had an outline like a holly leaf, with as many as five corners (one at each corner and one at the lower end).[6] In different artwork corners are depicted as missing, for instance rounding the lower section of the instrument so that there were no corners there, but only the point at the bottom.[6] An illustrated example would be the mermaids from Brunetto Latini's "Li livres dou tresor". A carved example would be from the Strasbourg Cathedral.[8]

T-shaped citoles had a prominent T shape at the top of the instrument, where the shoulder projections stuck out. Examples in illustration include the Queen Mary Psalter citoles. Carved examples include citoles at the Strasbourg Cathedral.[9]

Strings

Most depictions of the citole in manuscript drawings and sculpture show it strung with three strings. However, some show more strings, instruments strung in three, four, or five individual strings. The British Museum citole originally had pegs for six strings (the holes covered up when the instrument was converted to violin and revealed under X-Ray photography). On that instrument the neck isn't wide enough for six individual strings, as strung on a modern guitar. One possible arrangement for those six strings would be three courses of two strings. This would be similar to depictions in sculpture, including a citole sculpture mounted at the Collegiate church of Santa María la Mayorj, which has been interpreted as having three courses (two with two strings, one with a single string).[10][11]

Soundholes

Two different styles of soundholes are present in illustrations. One type looks like the soundholes on lutes, a circle cut from near the center of the soundboard in a large, elaborate circular carving called a rose. The citole roses are not as elaborate as the lute roses would be in later centuries.

Another type of soundhole consists of holes drilled in the soundboard and sometimes on the instrument's sides. The holes on the soundboard were cut at the four corners of the instrument. Additionally, holes have been cut into a circle, positioned where a rose would be if one were present.

Origins

Winternitz's theory, a continuous chain

Instruments do not always change in families. A luthier can see or dream of a feature and add it to an existing instrument or create it from scratch. However, instruments can also be thought of as coming from families, with features in common that exist in different instruments. At the Congress of the Galpin Society, Cambridge, June–July, 1959, Dr. Emanuel Winternitz of Yale University lectured about this evolution in instruments, saying, that although musical instruments are adapted to changes and develop new "features and organs", they tend to retain old "useless features" because of customer expectations.[13][14] He saw this pattern in the transformation of the cithara lyre into the citole into the cittern and talked about a "gradual and continuous" chain of instruments.[14][15]

To Winternitz, in the Stuttgart Psalter the old features were visible in its 9th-Century illustrations of the cythara. The instrument had a "superstructure" that reminded him of the "yoke" on the cithara lyre and "enormous ornamental wings" that were remains from the cithara lyre's arms.[16]

Under the theory, a neck was constructed between the two arms of the lyre, and then the arms of the lyre became vestigial, as "wings" (on the cittern "buckles").[15] Pictures from the 9th Century books, the Charles the Bald Bible and the Utrecht Psalter, illustrate this theory.[15] The development continued from the early cithara lyre, through the forms of instruments (called generically cithara), through the citole, and becoming the cittern.[14] Winternitz credited a Professor Westwood for making the Utrecht Psalter discoveries, quoting Westwood's 1859 paper, Archaological Notes of a Tour in Denmark, Prussia, and Holland: "...frequently shows the ancient kithara side by side with an instrument that has the body of a kithara but a neck in place of the yoke, in other words, a cittern, that is if we want to project this term as far back as the 9th century. The frets are usually carefully indicated on the neck, the graceful curvature of the wings corresponds precisely to that of the arms of the kitharas nearby."[16]

The mention of yoke and wings on the cytharas from the Stuttgart Psalter is confusing, as the instruments are very plain and lacking decorations. However, it is possible that when Winternitz referred to the yoke and wings, he was talking about the Utrecht Psalter, as he did in the very next sentence, for the description fits the images from that document.

Earlier variant of the theory, Greeks in Asia Minor

The theory was a variation of an earlier theory, talked about in the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica's articles about the guitar, cithara and rotta, which were written by Kathleen Schlesinger.[17] Where Winternitz focused on the cittern, Schlesinger concentrated on bringing the chain of instrument evolution to the guitar. Schlesinger believed that the instrumental change that adapted the lyre into the guitar-like instruments took place among the Greeks in the Anatolian Peninsula.[18] She saw in the drawings in the Utrecht Psalter as proof of that transformation.[18]

One point of controversy that continues today is the point of view against the idea of the guitar evolving from Arab introduced instruments.[19] Schlesinger wrote about various instruments including the guitarra latina and the guitarra morisca. Scholars have not conclusively straightened out these instruments.[19] The guitarra latina is one that has also been called the citole, due to the inability to know from the images whether it had a free neck (in which a hand can move up and down the neck freely, as on a guitar) or a deep neck with thumb hole (in which the range on the neck is limited to what the fingers can reach from the thumbhole.

Kathleen Schlesinger wrote the cithar article and talked plainly about the transformation of the ancient instrument into the modern: "...it was among the Greeks of Asia Minor that the several steps in the transition from cithara into guitar took place. The first of these steps produced the rotta (q.v.), by the construction of body, arms and transverse bar in one piece...the cithara with rectangular body, while from the cithara with a body having the curve of the lower half of the violin was produced a rotta with the outline of the body of the guitar. Both types were common in Europe until the 14th century, some played with a bow, others twanged by the fingers, and bearing indifferently both names, cithara and rotta....The addition of a finger-board, stretching like a short neck from body to transverse bar, leaving on each side of the finger-board space for the hand to pass through in order to stop the strings, produced the crwth or crowd (q.v.), and brought about the reduction in the number of the strings to three or four. The conversion of the rotta into the guitar (q.v.) was an easy transition effected by the addition of a long neck to a body derived from the oval rotta. When the bow was applied the result was the guitar or troubadour fiddle."

From the rotta article: "...The rotta represents the first step in the evolution of the cithara, when arms and cross-bar were replaced by a frame joined to the body, the strings being usually restricted to eight or less...The next step was the addition of a finger-board and the consequent reduction of the strings to three or four, since each string was now capable of producing several notes...As soon as the neck was added to the guitar-shaped body, the instrument ceased to be a rotta and became a guitar (q.v.), or a guitar-fiddle (q.v.) if played with the bow."

From the guitar article: "The guitar is derived from the cithara both structurally and etymologically...we shall be justified in assuming that the instrument, which required skill in construction, died out in Egypt and in Asia before the days of classic Greece, and had to be evolved anew from the cithara by the Greeks of Asia Minor. That the evolution should take place within the Byzantine Empire or in Syria would be quite consistent with the traditions of the Greeks and their veneration for the cithara, which would lead them to adapt the neck and other improvements to it, rather than adopt the rebab, the tanbur or the barbiton from the Persians or Arabians...The transitions whereby the cithara acquired a neck and became a guitar are shown in the miniatures of a single MS., the celebrated Utrecht Psalter, which gave rise to so many discussions. The Utrecht Psalter was executed in the diocese of Reims in the 9th century, and the miniatures, drawn by an Anglo-Saxon artist attached to the Reims school, are unique, and illustrate the Psalter, psalm by psalm. It is evident that the Anglo-Saxon artist, while endowed with extraordinary talent and vivid imagination, drew his inspiration from an older Greek illustrated Psalter from the Christian East, where the evolution of the guitar took place."

Another theory, plucked fiddles

Musicologist Laurence Wright, who is credited with clearing up the differences between the gittern and the citole wasn't fully convinced.[14] He said that the citole could only have been created from the plucked fiddles that were common in Europe at the time (examples include the guitar fiddle, and the early vielle and viol).[14] Three points he made were that a continuous record of instruments with the vestigial wings on the upper corners did not exist for the preceding 200-year period before 1200 a.d., that the Spanish instruments thought to be citoles (such as those in the Cantigas de Santa Maria) did not have the vestigial wings, and that the name citole did not exist before the 12th Century.[14]

Cythara, word for lyre and plucked fiddles

The word cythara was used generically for stringed instruments of medieval and Renaissance eras.[14] It was the Latin name for "cithara" or kithara, the Greek lyre.[14] The name may have been popular for its "magical" connotations, a belief that the music from a stringed instrument could sway listeners emotions.[14] Lyres were replaced in medieval times by "plucked fiddles" (such as the guitar fiddle), which were plucked until the bow arrived in the 10th Century.[14] The remaining lyres as well as the fiddles were adapted to fit the bow, after its arrival.[14] One example of an early bowed fiddle was the Byzantine lyra; an example of a bowed lyre that survived until modern times is the crwth.

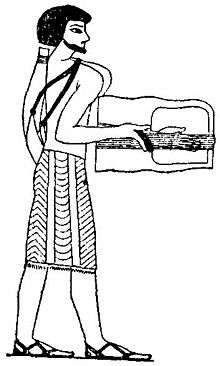

In the 9th Century, one of the instruments that cythara was actively used to name was a large plucked or strummed instrument; pictures show it being played with a plectrum.[20] Pictures of the instrument illustrated in the Stuttgart Psalter all have the word "cythara" near the instrument in the text.[20] The players hold the instrument in a distinct manner similar to the way that citole players were shown to hold their instruments, resting the instrument on the playing arm, and bringing their forearm and wrist to the strings from underneath the body of the instrument. In contrast, players of lute family instruments, such as the gittern, mandore, or lute did not hold the instrument this way. Instead of keeping their arms below the instrument, they allowed their arm and wrist to move parallel to the soundboard, as a guitar player does today.

One picture of the cythara shows it held a different way. The player is holding it vertically, resting on his lap or knee, supporting the neck with his left hand and having a free right hand to play. Citole players have also been shown holding their instruments vertically.[21]

Gallery

|

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Citole. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Citole. |

- Two photos of Spanish citoles and link to a history paper in Spanish

- Exhaustive research on the citole and its development. Comparisons to gittern and cittern.Strasbourg Cathedral carvings showing citoles.]

- The ebook "Dante's Journey to Polyphony" by Francesco Ciabattoni discusses what was known of the citole/cithara in the early 13th century.

- Gittern

- Modern built citole with good pictures showing the double neck and the taper of the top and bottom of the instrument.

- Modern built citole with smaller thumbhole.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Citole". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 397.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Citole". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 397.- Kevin, P. (2008). "A musical instrument fit for a queen: the metamorphosis of a Medieval citole" (PDF). The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin,. 2: pp. 13–28.

- Robinson, James; Speakman, Naomi; Buehler-McWilliams, Kathryn, eds. (2015). The British Museum Citole: New Perspectives (PDF). London: The British Museum Press. ISBN 9780861591862.

- 1 2 3 Butler, Paul. "The Citole Project". crab.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

The citole is definite ancestor of the cittern.

- 1 2 Robinson & 2015 page 1

- 1 2 British Museum Highlights

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 6, CITOLE

- ↑ Baker, Paul. "The Gittern and Citole". Retrieved 4 December 2016.

It took some extremely painstaking cross-referencing by a guy called Laurence Wright to sort it all out. The final conclusion was pretty definite, and appeared in the Galpin Society Journal in May 1977. The information took a while to filter through the early music community though, so beware of any reference to the gittern, citole, or mandora in pre-1985 texts. Check the illustrations and make sure what instrument is being discussed. The following notes use Wright's revised names.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rault, Christian. "The emergence of new approaches to plucked instruments, 13th - 15th centuries.". christianrault.com. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 Kevin & 2008 page 24

- ↑ Strujak, Julien. "Les instruments à cordes pincées de la Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

(First published in September 2011 in “le Joueur de Luth”, bulletin of the Société Française de Luth)...The statue of the musician in the citole "holly leaf" currently at the museum is also in very good condition.

- ↑ Strujak, Julien. "Les instruments à cordes pincées de la Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

(First published in September 2011 in “le Joueur de Luth”, bulletin of the Société Française de Luth)...[talking about the 1924 condition of one of the cathedral's statues which had since been restored] In its state of 1924, the "T" citole presents a particular but elegant form: the fairly straight body is flared at the level of the shoulders in two "fins", which gives it a silhouette in "T".

- ↑ "REYES MUSICOS DEL PORTICO DE LA MAJESTAD, Estudio y comentarios de Luis Delgado, Nº1 REY MUSICO CON CITOLA". argoceramica.com. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

El instrumento esta dotado de cinco cuerdas, agrupadas en tres ordenes. Comparativamente con las numerosas apariciones de este instrumento con otras fuentes iconográficas, podríamos sugerir que tanto la prima como la segunda fueran cuerdas dobles, quedando un bajo simple en la tercera. [translated to English:] The instrument is endowed with five strings, grouped in three orders. Compared with the numerous appearances of this instrument with other iconographic sources, we could suggest that both the prime and the second were double strings, leaving a simple bass in the third.

- ↑ Gamelán. "MusicArt Nº1 REY MÚSICO CON CÍTOLA". pinterest.com. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

[Photo and text]Saved from argotceramica.com...MusicArt Nº18 REY MÚSICO CON CÍTOLA...Comparativamente con las numerosas apariciones de este instrumento con otras fuentes iconográficas, podríamos sugerir que tanto la prima como la segunda fueran cuerdas dobles, quedando un bajo simple en la tercera.

- ↑ Winternitz, Emanuel (July–December 1961). "THE SURVIVAL OF THE KITHARA AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE CITTERN, A Study in Morphology". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 24 (3/4): 213. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Winternitz, Emanuel (July–December 1961). "THE SURVIVAL OF THE KITHARA AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE CITTERN, A Study in Morphology". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 24 (3/4): 210. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Segerman, Ephraim (April 1999). "A Short History of the Cittern". The Galpin Society Journal. 52: 106–107. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

...the drawings of the Utrecht Psalter...a similar instrument in a sixth century mosaic in Libya...a drawing in a 9th Century bible of Charles le Chauve which shows an instrument that was a cross between a kithara and a wide short lute...the thesis that he proposed was that these instruments were links in the gradual and continuous transformation of the kithara to the cittern.

- 1 2 3 Butler, Paul. "THE CITOLE PROJECT, MORPHOLOGY IN REPRESENTATION: WHAT DOES A CITOLE LOOK LIKE?". crab.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

The image on the left is from the Bible of Charles the Bald from the 9th century -the one on the right, from the Utrecht Psalter, Psalm 43, also from the 9th century. These show the cithara in transition to the new form of instrument. The left shows the cithara/lyra having acquired a fingerboard, though the arms still support the top crossbar, even if ornamentally. The figure from Utrecht shows the neck now free of the arms, but the vestages of the arms still present in the broad curls at the top of the body of the instrument where it joins the neck. It is from instruments like these of the 9th century that the citole/gittern develops.

- 1 2 Winternitz, Emanuel (July–December 1961). "THE SURVIVAL OF THE KITHARA AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE CITTERN, A Study in Morphology". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 24 (3/4): 212. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

Here again a decorative superstructure reminds us of the yoke, and the curving arms of the kithara are retained in the enormous ornamental wings. This, like the other illustrations of the Stuttgart Psalter, reflects contemporary musical usage, that is native, barbaric, or rather pagan tradition soon after it was modified by the spread of the Gospel,...

- ↑ The Reader's Guide to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Company, 1913 p. 185

- 1 2 Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). "

Guitar Fiddle". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. Wikisource. "From such evidence as we now possess, it would seem that the evolution of the early guitar with a neck from the Greek cithara took place under Greek influence in the Christian East. The various stages of this transition have been definitely established by the remarkable miniatures of the Utrecht Psalter."

Guitar Fiddle". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. Wikisource. "From such evidence as we now possess, it would seem that the evolution of the early guitar with a neck from the Greek cithara took place under Greek influence in the Christian East. The various stages of this transition have been definitely established by the remarkable miniatures of the Utrecht Psalter." - 1 2 Rey Marco, Juan José. ""Un instrumento punteado del siglo XIII en España", I, II, III (y IV)" (PDF). Retrieved 4 December 2016.

[English translation] The problem posed by this instrument is evidently that of its origin. In fact, if we accept the name "Latin guitar", we will have to discard a path of evolution through the Arabs. According to the studies of C. Geiringer (12), the adjective "latinus" is equivalent to "indigenous", the "Latin guitar" or autochthonous, opposes the "Moorish guitar" from foreign origin.

- 1 2 "Dante's Journey to Polyphony By Francesco Ciabattoni".

There is evidence of citharae shaped like a lute, that is with a neck and an elongated body, even before the 12th century: the Golden Psalter of St Gall depicts King David wielding an instrument...this instrument resembles a lute more than a cythara [lyre]...Further evidence appears in the Stuttgart Psalter...several images of an instrument...in the text, next to all these miniatures, the instrument is called a cythara...

- ↑ Rault, Christian. "plate4.jpg". christianrault.com. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

[photo caption from main page, http://www.christianrault.com/fr/publications/the-emergence-of-new-approaches-to-plucked-instruments-13th-15th-centuries] Plate 4 : Toro Collegiate: West Door, ca 1240.

_by_Benedetto_Antelami%2C_Parma.jpg)