Chumash people

|

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (2,000[1]–5,000[2]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

|

English and Spanish Chumashan languages | |

| Religion | |

|

Traditional tribal religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

Barbareño, Ventureño, Ynezeño, Purismeño, Obiseño[3] |

The Chumash are a Native American people who historically inhabited the central and southern coastal regions of California, in portions of what is now San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura and Los Angeles counties, extending from Morro Bay in the north to Malibu in the south. They also occupied three of the Channel Islands: Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel; the smaller island of Anacapa was likely inhabited seasonally due to the lack of a consistent water source.[4][5]

Modern place names with Chumash origins include Cayucos, Malibu, Lompoc, Ojai, Pismo Beach, Point Mugu, Port Hueneme, Piru, Lake Castaic, Saticoy, Simi Valley and Somis.

Archaeological research demonstrates that the Chumash have deep roots in the Santa Barbara Channel area and lived along the southern California coast for millennia.

History

Chumash environment before European contact (1400 AD)

The Chumash resided between the Santa Ynez Mountains and the California coasts where rivers and tributaries abound. Inside and around the modern-day Santa Barbara region, the Chumash lived with a bounty of resources. The tribe lived in an area of three environments: the interior, the coast, and the Northern Channel Islands.[6] These provided a diverse array of materials to support the Chumash lifestyle.

The interior is composed of the land outside the coast and spanning the wide plains, rivers, and mountains. The coast covers the cliffs and land close to the ocean and, in reference to resources, the areas of the ocean from which the Chumash harvested. The Northern Channel Islands lie off the coast of the Chumash territory.

All of the California coastal-interior has a Mediterranean climate due to the incoming ocean winds.[7] The mild temperatures, save for winter, made gathering easy; during the cold months, the tribespeople harvested what they could and supplemented their diets with stored foods. What villagers gathered and traded during the seasons changed depending on where they resided.[8]

With coasts populated by masses of species of fish and land densely covered by trees and animals, the Chumash had a diverse array of food. Abundant resources and a winter rarely harsh enough to cause concern meant the tribe lived a sedentary lifestyle in addition to a subsistence existence. Villages in the three aforementioned areas contained remains of sea mammals, indicating that trade networks existed for moving materials throughout the Chumash territory.[9] Such connections spread out the land’s wealth, allowing the Chumash to live comfortably without agriculture.

Chumash diet before 1400 AD

The closer a village was to the ocean, the greater its reliance on maritime resources.[10] Due to advanced canoe designs, coastal and island people could procure fish and aquatic mammals from farther out. Shellfish were a good source of nutrition: relatively easy to find and abundant. Many of the favored varieties grew in tidal zones.[11] Shellfish grew in abundance during winter to early spring; their proximity to shore made collection easier. Some of the consumed species included mussels, abalone, and a wide array of clams. Haliotis rufescens (red abalone) was harvested this species along the Central California coast in the pre-contact era.[12] The Chumash and other California Indians also used red abalone shells to make a variety of fishhooks, beads, ornaments, and other artifacts.

Ocean animals such as otters and seals were thought to be the primary meal of coastal tribes people, but recent evidence shows the aforementioned trade networks exchanged oceanic animals for terrestrial foods from the interior. Any village could acquire fish, but the coastal and island communities specialized in catching not just smaller fish, but also the massive catches such as swordfish.[13] This feat, difficult even for today’s technology, was made possible by the tomol plank canoe. Its design allowed for the capture of deepwater fish, and it facilitated trade routes between villages.[13]

Before contact with Europeans, coastal Chumash relied less on terrestrial resources than they did on maritime; vice versa for interior Chumash.[14] Regardless, they consumed similar land resources. Like many other tribes, deer were the most important land mammal the Chumash pursued; deer were consumed in varying amounts across all regions, which cannot be said for other terrestrial animals. Interior Chumash placed greater value on the deer, to the extent that they had unique hunting practices for them. They dressed as deer and grazed alongside the animals until the hunters were in range to use their arrows.[14] Even Chumash close to the ocean pursued deer, though in understandably fewer numbers, and what more meat the villages needed they acquired from smaller animals such as rabbits and birds.

Plant foods composed the rest of Chumash diet, especially acorns, which were the staple food despite the work needed to remove their inherent toxins. They could be ground into a paste that was easy to eat and store for years.[15] Coast live oak provided the best acorns; their mush would be served usually unseasoned with meat and/or fish.[16]

The beginning of the Chumash tribe

Native Americans have lived along the California coast for at least 13,000 years. The first settlement started over 13,000 years ago near the Santa Barbara coast. The name Chumash means “bead maker” or “seashell people” being that they originated near the Santa Barbara coast. The Chumash tribes near the coast benefited most with the “close juxtaposition of a variety or marine and terrestrial habitats, intensive upwelling in coastal waters, and intentional burning of the landscape made the Santa Barbara Channel region one of the most resource abundant places on the planet”.[17] Before the mission period, the Chumash lived in over 150 independent villages, speaking variations of the same language. Much of their culture consisted of basketry, bead manufacturing and trading, cuisine of local abalone and clam, herbalism which consisted of using local herbs to produce teas and medical reliefs, rock art, and the scorpion tree.[18] The scorpion tree was significant to the Chumash as shown in its arborglyph: a carving depicting a six-legged creature with a headdress including a crown and two spheres. The shamans participated in the carving which was used in observations of the stars and in part of the Chumash calendar.

European contact

Europeans first visited the Chumash in 1542. They were met by sailing vessels under the command of Juan Cabrillo. With the arrival of the Europeans “came a series of unprecedented blows to the Chumash and their traditional lifeways. Anthropologists, historians, and other scholars have long been interested in documenting the collision of cultures that accompanied the European exploration and settlement of the Americas.”[17] Spain settled on the territory of the Chumash in 1770. They founded colonies, bringing in missionaries to begin Christianizing Native Americans in the region. Due to the large mission and Christian influence, Chumash villages began moving to many missions springing up along the coast.

Much of the Chumash’s population was diminished due to Old World diseases brought over by the Europeans. The settlement of the Spanish also devastated the Chumash culture.

The Chumash reservation, established in 1901, encompasses 127 acres. No native Chumash speak their own language since Inesño, whose last speaker died in 1965. Today, the Chumash are estimated to have a population of 5,000 members. Many current members can trace their ancestors to the five islands of Channel Island National Park.

Chumash bands

One Chumash band, the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Mission Indians of the Santa Ynez Reservation is a federally recognized tribe, and other Chumash people are enrolled in the federally-recognized Tejon Indian Tribe of California. There are 14 bands of Chumash Indians.[19]

- Barbareno Chumash, affiliated with the Taynayan missions and the Kashwa reservations.

- Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, their historical territory, north of Los Angeles, includes parts of the coastal counties of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, Kern, and Ventura. The Coastal band of the Chumash Nation applied for recognition in 1981.[20]

- Cuyama Chumash, from the Cuyama Valley

- Island Chumash, from the Channel Islands

- Kagismuwas Chumash, from the southwestern-most region of the ancestral Chumash land. Their historical lands are now part of Vandenberg Air Force Base.

- Los Angeles Chumash, formed when members of the traditional Malibu, Tejon, and Venura bands were relocated in the 19th century.

- Malibu Chumash, from the coast of Malibu. Descendants of this band can now be found among the Ventura, Coastal, Tejon, and San Fernando Valley bands.

- Monterey Chumash, from the Monterey peninsula.

- Samala, or Santa Ynez Chumash. The Santa Ynez Chumash people in 2012 went to federal count to regain more land. The Bureau of Indian Affairs approved the request; the land was to go toward tribal housing and a Chumash Museum and Cultural Center. However, protesters and anti-tribal groups have spent approximately $2 million to disrupt or stop the land acquisition.[21]

- San Fernando Valley Chumash, once slave laborers at the San Fernando Valley Mission. They intermarried other tribes who also worked at the mission.

- San Luis Obispo Chumash, northwestern-most Chumash people.

- Tecuya Chumash, most of this band of Chumash tribe were probably Kagismuwas. This band was established as an anti-colonial group, who took residence in the Tecuya Canyon along with the Tejon Chumash.

- Tejon Chumash, part of the Kern County Chumash Council. Tejon is the Spanish word for "badger," and its name was given to the Tejon Rancheria.

- Ventura Chumash, lives in the traditional Chumash domain of the Owl Clan.

Population

Estimates for the precontact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. The anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber thought the 1770 population of the Chumash might have been about 10,000.[22] Alan K. Brown concluded that the population was about 15,000.[23] Sherburne F. Cook, at various times, estimated the aboriginal Chumash as 8,000, 13,650, 20,400, or 18,500.[24]

Some scholars[25] have suggested the Chumash population may have declined substantially during a "protohistoric" period (1542–1769), when intermittent contacts with the crews of Spanish ships, including those of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo's expedition, who wintered in the Santa Barbara Channel in AD 1542–43, brought disease and death. The Chumash appear to have been thriving in the late 18th century, when Spaniards first began actively colonizing the California coast. Whether the deaths began earlier with the contacts with ships' crews or later with the construction of several Spanish missions at Ventura, Santa Barbara, Lompoc, Santa Ynez, and San Luis Obispo, the Chumash were eventually devastated by Old World diseases such as influenza and smallpox, to which they had no immunological resistance. By 1900, their numbers had declined to just 200, while current estimates of Chumash people today range from 2,000[1] to 5,000.[2]

Languages

Several related languages under the name "Chumash" (from čʰumaš /t͡ʃʰumaʃ/, meaning "Santa Cruz Islander") were spoken. Few, if any, living native speakers remain, although they are well documented in the unpublished fieldnotes of linguist John Peabody Harrington. Especially well documented are the Barbareño, Ineseño, and Ventureño dialects. Several Chumash families are working to revitalize the language.[26] The native name for Chumash in Ineseño/Barbareño is s?amala /s?amala/.

Culture

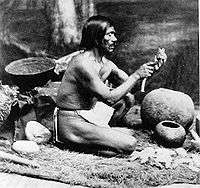

The Chumash were hunter-gatherers and were adept at fishing at the time of Spanish colonization. They are one of the relatively few New World peoples who regularly navigated the ocean (another was the Tongva, a neighboring tribe to the south). Some settlements built a plank boat (tomol), which facilitated the distribution of goods and could be used for whaling.

Basketry

Anthropologists have long collected Chumash baskets. Two of the finest collections are at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, and the Musée de l'Homme (Museum of Mankind) in Paris. The Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History is believed to have the largest collection of Chumash baskets.

Bead manufacture and trading

The Chumash of the Northern Channel Islands were at the center of an intense regional trade network. Beads made from Olivella shells were manufactured on the Channel Islands and used as a form of currency by the Chumash.[27] These shell beads were traded to neighboring groups and have been found throughout Alta California. Over the course of late prehistory, millions of shell beads were manufactured and traded from Santa Cruz Island. It has been suggested that exclusive control over stone quarries used to manufacture the drills needed in bead production could have played a role in the development of social complexity in Chumash society.[27]

Cuisine

Foods historically consumed by the Chumash include several marine species, such as black abalone,[28] the Pacific littleneck clam,[28] red abalone,[28] the bent-nosed clam,[28] ostrea lurida oysters,[28] Pacific littleneck clams,[28] angular unicorn snails,[28] and the butternut clam.[29] They also made flour from the dried fruits of the laurel sumac.[30]

Herbalism

Herbs used in traditional Chumash medicine include thick-leaved yerba santa, used to keep airways open for proper breathing;[31] laurel sumac, the root bark of which was used to make a herbal tea for treating dysentery;[30] and black sage, the leaves and stems were made into a strong sun tea. This was rubbed on the painful area or used to soak one's feet. The plant contains diterpenoids, such as aethiopinone and ursolic acid, which are known pain relievers.[32]

The Chumash formerly practiced an initiation rite involving the use of sacred datura (moymoy in their language). When a boy was 8 years old, his mother would give him a preparation of it to drink. This was supposed to be a spiritual challenge to help him develop the spiritual wellbeing required to become a man. Not all of the boys survived the poison.[33]

Rock art

Remains of a developed Chumash culture, including rock paintings apparently depicting the Chumash cosmology, such as Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park, can still be seen.

Scorpion tree

A centuries-old oak tree in California is considered to have a Chumash arborglyph, a carving of a six-legged creature with a head-dress including a crown and two spheres. Previously thought to have been carved by cowboys, it was visited in 2007 by paleontologist Rex Saint Onge, who identified the three-foot carving as being of Chumash origin and related to other Chumash cave paintings in California. Further studies have led Saint Onge to believe these are not simply the work of Chumash, shamans who were conscious observations of the stars and part of a Chumash calendar.[34]

History

Before Spanish contact

Archaeological evidence of Native American presence in what were later the Chumash lands date to at least 11,000 years before present.[35] Sites of the Millingstone Horizon date from 7000 cal BC to 4500 cal BC and show evidence of a subsistence system focused on the processing of seeds with metates and manos.[36] During that time, people used bipointed bone objects and line to catch fish and began making beads from shells of the marine olive snail (Olivella biplicata).[37]

While droughts were not uncommon in the centuries of the first millennium AD, a population explosion occurred with the coming of the medieval warm period. "Marine productivity soared between 950 and 1300 as natural upwelling intensified off the coast."[38]

Some researchers believe that the Chumash may have been visited by Polynesians between AD 400 and 800, nearly 1,000 years before Christopher Columbus reached the Americas.[39] Although the concept is rejected by most archaeologists who work with the Chumash culture (and this contact has left no genetic legacy), others have given the idea greater plausibility.[40][41]

The Chumash advanced sewn-plank canoe design, used throughout the Polynesian Islands but unknown in North America except by those two tribes, is cited as the chief evidence for contact. Comparative linguistics may provide evidence as the Chumash word for "sewn-plank canoe", tomolo'o, may have been derived from kumula'au, the Polynesian word for the redwood logs used in that construction. However, the language comparison is generally considered tentative. Furthermore, the development of the Chumash plank canoe is fairly well represented in the archaeological record and spans several centuries.[42][43]

Spanish arrival and the Mission era

Chumash people first encountered Europeans in the autumn of 1542, when two sailing vessels under Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo arrived on the coast from Mexico. Cabrillo died and was buried on San Miguel Island, but his men brought back a diary that contained the names and population counts for many Chumash villages, such as Mikiw. Spain claimed what is now California from that time forward, but did not return to settle until 1769, when the first Spanish soldiers and missionaries arrived with the double purpose of Christianizing the Native Americans and facilitating Spanish colonization. By the end of 1770, missions and military presidios had been founded at San Diego to the south of Chumash lands and Monterey to their north.[44]

The Chumash people moved from their villages to the Franciscan missions between 1772 and 1817. Mission San Luis Obispo, established in 1772, was the first mission in Chumash-speaking lands, as well as the northernmost of the five missions ever constructed in those lands. Next established, in 1782, was Mission San Buenaventura on the Pacific Coast near the mouth of the Santa Clara River. Mission Santa Barbara, also on the coast, and facing out to the Channel Islands, was established in 1786. Mission La Purisima Concepción was founded along the inland route from Santa Barbara north to San Luis Obispo in 1789. The final Franciscan mission to be constructed in native Chumash territory was Santa Ynez, founded in 1804 on the Santa Ynez River with a seed population of Chumash people from Missions La Purisima and Santa Barbara. To the southeast, Mission San Fernando, founded in 1798 in the land of Takic Shoshonean speakers, also took in large numbers of Chumash speakers from the middle Santa Clara River valley. While most of the Chumash people joined one mission or another between 1772 and 1806, a significant portion of the native inhabitants of the Channel Islands did not move to the mainland missions until 1816.[45]

Contemporary times

See also the Chumash Revolt of 1824, a Chumash uprising against the presence of the Spanish in The Californias.

The first modern tomol was built and launched in 1976 as a result of a joint venture between Quabajai Chumash of the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation and the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. Its name is Helek/Xelex, the Chumash word for falcon. The Brotherhood of the Tomol was revived and her crew paddled and circumnavigated around the Santa Barbara Channel Islands on a 10-day journey, stopping on three of the islands. The second tomol, the Elye'wun ("swordfish"), was launched in 1997.

On September 9, 2001, the first "crossing" in the Chumash tomol, from the mainland to Channel Islands, was sponsored by the Chumash Maritime Association and the Barbareno Chumash Council. Several Chumash bands and descendants gathered on the island of Limuw (the Chumash name for Santa Cruz Island) to witness the Elye'wun being paddled from the mainland to Santa Cruz Island. Their journey was documented in the short film "Return to Limuw" produced by the Ocean Channel for the Chumash Maritime Association, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, and the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum. The channel crossings have become a yearly event hosted by the Barbareno Chumash Council.

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash is a federally recognized Chumash tribe. They have the Santa Ynez Reservation located in Santa Barbara County, near Santa Ynez. Chumash people are also enrolled in the Tejon Indian Tribe of California.

In addition to the Santa Ynez Band, the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, and the Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians are attempting to gain federal recognition. Other Chumash tribal groups include the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, descendants from the San Luis Obispo area, and the Barbareno Chumash Council, descendants from the greater Santa Barbara area.

The publication of the first Chumash dictionary took place in April 2008. Six hundred pages long and containing 4,000 entries, the Samala-English Dictionary includes more than 2,000 illustrations.[46]

The documentary film 6 Generations: A Chumash Family History features Mary Yee, the last speaker of the Barbareño Chumash language.[47]

A Chumash Indian museum is in Thousand Oaks, California. It has Chumash artifacts, displays illustrating Chumash daily life, and a recreated Chumash village nestled underneath beautiful oak trees by a stream. The museum is surrounded by hiking trails.[48]

As of 2013, a reconstruction of a Chumash village is open in Malibu, "on a bluff overlooking the Pacific."[49]

Santa Ynez history

Mexico seized control of the missions in 1834. Tribespeople either fled into the interior, attempted farming for themselves and were driven off the land, or were enslaved by the new administrators. Many found highly exploitative work on large Mexican ranches. After 1849 most Chumash land was lost due to theft by Americans and a declining population, due to the effects of violence and disease. The remaining Chumash began to lose their cohesive identity. In 1855, a small piece of land (120 acres) was set aside for just over 100 remaining Chumash Indians near Santa Ynez mission. This land ultimately became the only Chumash reservation, although Chumash individuals and families also continued to live throughout their former territory in southern California. Today, the Santa Ynez band lives at and near Santa Ynez. The Chumash population was between roughly 10,000 and 18,000 in the late 18th century. In 1990, 213 Indians lived on the Santa Ynez Reservation.[50]

Produce initiative

In December 2010, the Foodbank of Santa Barbara County was the proud recipient of a $10,000 grant from the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians Foundation to support expansion of the Produce Initiative. The Produce Initiative puts an emphasis on supplying fruits and vegetables to 264 local nonprofits and food programs. The foodbank distributes produce free of charge to member agencies to encourage healthy eating. Expanding produce accessibility to children is important to the foodbank and the newly operating Kids’ Farmers' Market program, an extension of the Produce Initiative, successfully achieves that goal.

The program trains volunteers to teach kids in after-school programs nutrition education and hands-on cooking instructions. This program currently operates at 12 sites countywide, including in the Santa Ynez Valley. After the children cook and eat a healthy meal, they get to take home a bag full of fresh produce, where they can help feed and cook for the whole family.[51] Obesity in children is a major health problem prevalent among Native Americans.[52]

To promote sustainable agriculture and healthy diets, the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Environmental Office and Education Departments' after-school program planted a community garden, which provided vegetables to the Elder's Council, beginning in 2013.[53] The Santa Ynez Valley Fruit and Vegetable Rescue, also known as Veggie Rescue, is another effort to improve food sourcing for the Santa Ynez.[54]

Casino controversy

There was a lawsuit filed on April 3, 2015 in federal court against the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Mission Indians by a group of citizens of Santa Ynez, CA. The lawsuit claims that the tribe is erroneously claiming that the property where they are building their 12-story high-rise hotel/casino expansion project is on federal "Tribal Trust Land" and part of a federal Indian reservation. The case has now been taken to a United States Federal Court.

Places of significance

Places of significant archaeological and historical value.[55]

- Albinger Archaeological Museum in Ventura – Chumash artifacts and history

- Burro Flats Painted Cave in Simi Valley – Chumash pictographs

- Carpinteria State Beach in Carpinteria – cave paintings depicting Chumash life

- Carpinteria Valley Museum of History and Historical Society in Carpinteria – Chumash artifacts and history

- Chumash Indian Museum in Thousand Oaks – exhibitions of artifacts and recreation of Chumash houses

- Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park in Santa Barbara – cave paintings

- Hollister Adobe Museum in San Luis Obispo – Chumash artifacts and exhibits

- La Purisima Mission State Historical Park in Lompoc – displays of mission life in reconstructed buildings

- Lompoc Museum in Lompoc – Chumash artifacts and history

- Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History in Los Angeles – anthropology and guided tours for Chumash natural history

- Mission San Luis Obispo Museum – Chumash artifacts and exhibits

- Morro Bay Museum of Natural History – docent presentations and Chumash exhibits

- Ojai Valley Museum and Historical Society in Ojai. Inland Chumash history.

- Painted Rock, Carrizo Plain Natural Heritage Reserve in San Luis Obispo County – cave paintings

- Port Hueneme Historical Society Museum in Port Hueneme - Chumash speakers (Distinguished Speaker Series) exhibit on Chumash history and artifacts

- San Buenaventura Mission Museum in Ventura – exhibits on Chumash history

- San Luis Obispo County Historical Museum – Chumash artifacts and exhibits.

- Santa Barbara Historical Society in Santa Barbara. Guided tours.

- Santa Barbara Mission in Santa Barbara. Local Chumash history and guided tours.

- Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library. Records of all California mission Indians. < http://www.sbmal.org>

- Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History – exhibits on Chumash Indians and natural history of Native Americans

- Santa Barbara Presidio – historical exhibits

- Santa Cruz Island – cave paintings in Olsen’s Cave:[56] More than 300,000 Chumash objects have been collected in the Channel Islands,[57] which was home to 10 villages and more than 1200 Chumash residents.[58]

- San Luis Obispo County Historical Museum – Chumash artifacts and exhibits

- Santa Ines Mission in Solvang – site of an early Spanish mission

- Santa Maria Valley Historical Society Museum – Chumash artifacts and exhibits

- Santa Rosa Island – cave paintings in Jones Cave. Thousands of artifacts of the island, which has been populated by the Chumash for more than 13,000 years, have been found.[59]

- Santa Ynez Indian Reservation (Samala) – the only Chumash Indian reservation[60]

- Satwiwa – ancient Chumash village and now museum in Newbury Park, CA

- Southwest Museum in Highland Park

- Ventura County Museum of History and Art in Ventura – exhibits on Chumash history with guided tours available

- Wishtoyo Chumash Discovery Village in Malibu -recreation of a Chumash village and exhibit of artifacts at the Nicholas Canyon County Beach

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chumash. |

- Burro Flats Painted Cave

- Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park, California

- Chumash traditional narratives

- Polynesian navigation

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

- Shalawa Meadow, California

Notes

- 1 2 "California Indians and Their Reservations: P. SDSU Library and Information Access. (retrieved 17 July 2010)

- 1 2 Native Inhabitants

- ↑ Pritzker, 121

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/chis/historyculture/nativeinhabitants.htm

- ↑ http://www.seathos.org/chumash-indians-on-the-channel-islands/

- ↑ Gamble 21.

- ↑ Timbrook 164.

- ↑ Gamble 228.

- ↑ Coombs and Plog 313.

- ↑ Gamble 6.

- ↑ Gamble 26–28.

- ↑ Hogan, C. M. Los Osos Back Bay. The Megalithic Portal, editor A. Burnham (2008).

- 1 2 (Gamble 156).

- 1 2 (Gamble 164).

- ↑ Gamble 23.

- ↑ Brittain 5.

- 1 2 (Newton 416).

- ↑ Barry.

- ↑ "Chumash Indians" (PDF). Chumash Indian Bands. Chumash Tribe. 19 June 2014.

- ↑ "Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation". YouTube. Aim Santa Barbra. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ↑ 2012. Indian Lands: Exploring Resolutions to Disputes Concerning Indian Tribes, State and Local Governments, and Private Landowners over Land Use and Development. N.p.

- ↑ A. L. Kroeber, p.883

- ↑ Brown, Alan K (1967). "The Aboriginal Population of the Santa Barbara Channel.". Reports of the University of California Archeological Survey. University of California (69).

- ↑ S. F. Cook, 1976

- ↑ Erlandson et al. 2001

- ↑ Mithun 1999:389–392.

- 1 2 Arnold 2001

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hogan, C. M. "Los Osos Back Bay". The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ↑ Intertidal Marine Invertebrates of the South Puget Sound (2008) Archived February 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Timbrook, Jan (1990). "Ethnobotany of Chumash Indians, California," based on collections by John P. Harrington". Economic Botany. 44 (2): 236–253. doi:10.1007/BF02860489.

- ↑ James D. Adams Jr, Cecilia Garcia (2005). "Palliative Care Among Chumash People". eCAM. 2 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh090. PMC 1142202

. PMID 15937554.

. PMID 15937554. - ↑ "Palliative Care Among Chumash People". Wild Food Plants. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ↑ Cecilia Garcia, James D. Adams (2005). Healing with medicinal plants of the west – cultural and scientific basis for their use. Abedus Press. ISBN 0-9763091-0-6.

- ↑ Kettman, Max "A Tree Carving in California: Ancient Astronomers?" Time Magazine 9 February 2010

- ↑ Dartt-Newton, Deana and Erlandson, Jon (Summer/Fall 2006), "Little Choice for the Chumash: Colonialism, Cattle, and Coercion in Mission Period California," The American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 3 & 4, 416

- ↑ Glassow et al. 2007:192–196

- ↑ King 1990:80–82, 106–107, 231

- ↑ Fagan, The Long Summer, 2004, p.222

- ↑ Did ancient Polynesians visit California? Maybe so., San Francisco Chronicle

- ↑ Jones, Terry L.; Kathryn A. Klar (June 3, 2005). "Diffusionism Reconsidered: Linguistic and Archaeological Evidence for Prehistoric Polynesian Contact with Southern California". American Antiquity. 70 (3): 457–484. doi:10.2307/40035309. JSTOR 40035309. Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on September 27, 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-06. and Adams, James D.; Cecilia Garcia; Eric J. Lien (January 23, 2008). "A Comparison of Chinese and American Indian (Chumash) Medicine". Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 7 (2): 219–25. doi:10.1093/ecam/nem188. PMC 2862936

. PMID 18955312. Retrieved 2008-03-06.. See also Terry Jones's homepage, California Polytechnic State University.

. PMID 18955312. Retrieved 2008-03-06.. See also Terry Jones's homepage, California Polytechnic State University. - ↑ For the argument against the Polynesian Contact Theory, see 2007 Arnold, J.E. "Credit Where Credit is Due: The History of the Chumash Oceangoing Plank Canoe." American Antiquity 72:196–209

- ↑ Arnold, Jeanne E. 1995.

- ↑ Gamble, Lynn H. 2002.

- ↑ Brown 1967

- ↑ McLendon and Johnson 1999

- ↑ Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians Publishes Language Dictionary. (http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS180466+21-Apr-2008+PRN20080421)

- ↑ Kettmann, Matt (2011-01-27). "Santa Barbara on Screen". The Santa Barbara Independent. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- ↑ http://chumashindianmuseum.com

- ↑ "Wishtoyo Foundation's Chumash Discovery Village, Malibu, CA". Wishtoyo Foundation. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- ↑ (Pritzker).

- ↑ Santa Barbara Independent.

- ↑ Blackwell, Amy Hackney (2014). "Childhood obesity." In The American Mosaic: The American Indian Experience. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Chumash Community Garden Update". Santa Ynez Chumash Environmental Office. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "Veggie Rescue". Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ Lynne McCall & Perry Rosalind. 1991. The Chumash People: Materials for Teachers and Students. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. San Luis Obispo, CA: EZ Nature Books. ISBN 0-945092-23-7. Page 72-73.

- ↑ http://www.pcas.org/Vol36N2/11Meighan.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/chis/historyculture/collections.htm

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/chis/planyourvisit/santa-cruz-island.htm

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/chis/planyourvisit/santa-rosa-island.htm

- ↑ http://www.santaynezchumash.org/reservation.html

References

- Arnold, Jeanne E. (ed.) 2001. The Origins of a Pacific Coast Chiefdom: The Chumash of the Channel Islands. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Arnold, Jeanne E. (1995). "Transportation Innovation and Social Complexity among Maritime Hunter-Gatherer Societies". American Anthropologist. 97: 733–747. doi:10.1525/aa.1995.97.4.02a00150.

- Brittain, A.; Evans, S.; Giroux, A.; Hammargren, B.; Treece, B.; Willis, A. (2011). "Climate action on tribal lands: A community based approach (resilience and risk assessment)". Native Communities and Climate Change. 5: 555.

- Brown, Alan K. (1967). "The Aboriginal Population of the Santa Barbara Channel". University of California Archaeological Survey Reports. 69: 1–99.

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976. The Conflict between the California Indian and White Civilization. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976. The Population of the California Indians, 1769–1970. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Coombs, G.; Plog, F. (1977). "The conversion of the chumash Indians: An ecological interpretation". Human Ecology. 5 (4): 309–328. doi:10.1007/bf00889174. JSTOR 4602423.

- Cordero R. The Ancestors Are Dreaming Us. News From Native California [serial online]. Spring2012 2012;25(3):4–27. Available from: Academic Search Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 22, 2014.

- Dartt-Newton, D.; Erlandson, J. M. (2006). "Little Choice for the Chumash: Colonialism, Cattle, and Coercion in Mission Period California". American Indian Quarterly. 30 (3/4): 416–430. doi:10.1353/aiq.2006.0020.

- Erlandson, Jon M.; Rick, Torben C.; Kennett, Douglas J.; Walker, Philip L. (2001). "Dates, demography, and disease: Cultural contacts and possible evidence for Old World epidemics among the Island Chumash". Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly. 37 (3): 11–26.

- Gamble, Lynn H. (2002). "Archaeological Evidence for the Origin of the Plank Canoe in North America". American Antiquity. 67 (2): 301–315. doi:10.2307/2694568.

- Gamble, L. H., & Enki Library eBook. (2008). The chumash world at European contact (1st ed.). Us: University of California Press. Retrieved from http://sjpl.enkilibrary.org/EcontentRecord/11197

- Glassow, Michael A., Lynn H. Gamble, Jennifer E. Perry, and Glenn S. Russell. 2007. Prehistory of the Northern California Bight and the Adjacent Transverse Ranges. In California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity. Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar, editors. New York and Plymouth UK: Altamira Press.

- Hogan, C.Michael. 2008. Morro Creek. Ed. A. Burnham.

- Jones, Terry L.; Klar, Kathryn A. (2005). "Diffusionism Reconsidered: Linguistic and Archaeological Evidence for Prehistoric Polynesian Contact with Southern California". American Antiquity. 70: 457–484. doi:10.2307/40035309.

- King, Chester D. 1991. Evolution of Chumash Society: A Comparative Study of Artifacts Used for Social System Maintenance in the Santa Barbara Channel Region before A.D. 1804. New York and London, Garland Press.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

- McLendon, Sally and John R. Johnson. 1999. Cultural Affiliation and Lineal Descent of Chumash Peoples in the Channel Islands and the Santa Monica Mountains. 2 volumes. Prepared for the Archeology and Ethnography Program, National Park Service by Hunter College, City University of New York and the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

- Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-29875-X.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Pritzker, Barry M. (2014). Chumash. In The American Mosaic: The American Indian Experience. Retrieved February 25, 2014, from http://americanindian2.abc-clio.com.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/

Sandos J. Christianization among the Chumash: an ethnohistoric perspective. American Indian Quarterly [serial online]. Winter91 1991;15:65–89. Available from: OmniFile Full Text Mega (H.W. Wilson), Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 22, 2014.

- Santa Barbara Independent. (2010, December 15). Chumash foundation $10,000 grant helps food bank serve healthy meals. *Timbrook, J.; Johnson, J. R.; Earle, D. D. (1982). "Vegetation burning by the chumash". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 4 (2): 163–186.

- Chumash Tribe sued over casino expansion

Further reading

- Black Gold Library System, 1997, Native Americans of the Central Coast (historic photographs). Ventura, CA, Black Gold Libraries

- Hudson, D. Travis and Thomas C. Blackburn. 1982-7. The Material Culture of the Chumash Interaction Sphere Volumes I–V. Anthropological Papers No. 25-31. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press.

- Hudson, D. Travis, Thomas Blackburn, Rosario Curletti and Janice Timbrook. 1977. The Eye of the Flute: Chumash Traditional History and Ritual as told by Fernando Librado Kitsepawit to John P. Harrington. Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

- Hudson, D. Travis, Janice Timbrook, and Melissa Rempe. 1977. Tomol: Chumash Watercraft as Described in the Ethnographic Notes of John P. Harrington. Anthropological Papers No. 9, edited by Lowell J. Bean and Thomas C. Blackburn. Socorro, NM: Ballena Press.

External links

- Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians

- Inezeño Chumash Language Tutorial

- Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation

- Antelope Valley Indian Museum at California Department of Parks and Recreation

- Native Cultures and the Maritime Heritage Program, NOAA

- Barbareno Chumash Council

- Northern Chumash Tribal Council

- Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park

- Chumash Singer and Storyteller Julie Tumamait-Stenslie

- Chumash Indian Museum, Thousand Oaks, CA

- Map of Chumash towns at the time of European Settlement

- "Wishtoyo Foundation's Chumash Discovery Village, Malibu, CA".