Chinese Rites controversy

The Chinese Rites controversy was a dispute among Roman Catholic missionaries over the religiosity of Confucianism and Chinese rituals during the 17th and 18th centuries. The debated centered over whether Chinese ritual practices of honoring family ancestors and other formal Confucian and Chinese imperial rites qualified as religious rites and thus incompatible with Catholic belief.[1][2] The Jesuits argued that these Chinese rites were secular rituals that were compatible with Christianity, within certain limits, and should thus be tolerated. The Dominicans and Franciscans, however, disagreed and reported the issue to Rome.

Rome's Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith sided with the Dominicans in 1645 by condemning the Chinese rites based on their brief. However, the same congregation sided with the Jesuits in 1656, thereby lifting the ban.[1] It was one of the many disputes between the Jesuits and the Dominicans in China and elsewhere in Asia, including Japan[3] and India.[4]

The controversy embroiled leading European universities; the Qing dynasty's Kangxi Emperor and several popes (including Clement XI and Clement XIV) considered the case; the offices of the Holy See also intervened. Near the end of the 17th century, many Dominicans and Franciscans had shifted their positions in agreeing with the Jesuits' opinion, but Rome disagreed. Clement XI banned the rites in 1704. In 1742, Benedict XIV reaffirmed the ban and forbade debate.[1]

In 1939, after two centuries the Holy See re-assessed the issue. Pope Pius XII issued a decree on December 8, 1939, authorizing Christians to observe the ancestral rites and participate in Confucius-honouring ceremonies.[1] The general principle of sometimes admitting native traditions even into the liturgy of the church, provided that such traditions harmonize with the true and authentic spirit of the liturgy, was proclaimed by the Second Vatican Council (1962–65).[5]

Background

Early adaptation to local customs

Unlike the American landmass, which had been conquered by military force by Spain and Portugal, European missionaries encountered in Asia united, literate societies that were as yet untouched by European influence or national endeavour.[6]

Alessandro Valignano, Visitor of the Society of Jesus in Asia, was one of the first Jesuits to argue, in the case of Japan, for an adaptation of Christian customs to the societies of Asia, through his Résolutions and Cérémonial.[7]

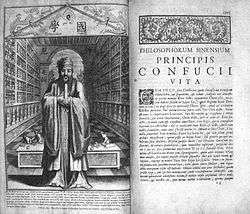

Matteo Ricci’s policy of accommodation

In China, Matteo Ricci reused the Cérémonial and adapted it to the Chinese context. At one point the Jesuits even started to wear the gown of Buddhist monks, before adopting the more prestigious silk gown of Chinese literati.[7] In particular, Matteo Ricci's Christian views on Confucianism and Chinese rituals, often called as "the Directives of Matteo Ricci" (Chinese: 利瑪竇規矩), was followed by Jesuit missionaries in China and Japan.[8]

In a decree signed on 23 March 1656, Pope Alexander VII accepted practices "favorable to Chinese customs", reinforcing 1615 decrees which accepted the usage of the Chinese language in liturgy, a notable exception to the contemporary Latin Catholic discipline which had generally forbidden the use of local languages.[9]

In the 1659 instructions given by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (known as the Propaganda Fide) to new missionaries to Asia, provisions were clearly made to the effect that adapting to local customs and respecting the habits of the countries to be evangelised was paramount:[10]

Do not act with zeal, do not put forward any arguments to convince these peoples to change their rites, their customs or their usages, except if they are evidently contrary to the religion [i.e., Catholic Christianity] and morality. What would be more absurd than to bring France, Spain, Italy or any other European country to the Chinese? Do not bring to them our countries, but instead bring to them the Faith, a Faith that does not reject or hurt the rites, nor the usages of any people, provided that these are not distasteful, but that instead keeps and protects them.— Extract from the 1659 Instructions, given to Mgr François Pallu and Mgr Lambert de la Motte of the Paris Foreign Missions Society by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith.[11][12]

Reception in China

The Kangxi Emperor was at first friendly to the Jesuit Missionaries working in China. He was grateful for the services they provided to him, in the areas of astronomy, diplomacy and artillery manufacture.[13] The Jesuits also made an important contribution to the Empire's military, with the diffusion of European artillery technology, and they directed the castings of cannons of various calibres. Jesuit translators Jean-François Gerbillon and Thomas Pereira took part in the negotiations of the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, where they helped translating.[12] By the end of the seventeenth century, the Jesuits also had made many converts.

In 1692, Kangxi issued an edict of toleration of Christianity (Chinese: 容教令 or Chinese: 正教奉傳[14]):[3][15]

The Europeans are very quiet; they do not excite any disturbances in the provinces, they do no harm to anyone, they commit no crimes, and their doctrine has nothing in common with that of the false sects in the empire, nor has it any tendency to excite sedition ... We decide therefore that all temples dedicated to the Lord of heaven, in whatever place they may be found, ought to be preserved, and that it may be permitted to all who wish to worship this God to enter these temples, offer him incense, and perform the ceremonies practised according to ancient custom by the Christians. Therefore let no one henceforth offer them any opposition.[16]

This edict elevates Christianity on equal status with Confucianism in China.[17] The Kangxi Emperor also hired several Jesuits in his court as scientists and artists.[18]

Controversy

The Society of Jesus (the Jesuit order) was successful in penetrating China and serving at the Imperial court. They impressed the Chinese with their knowledge of European astronomy and mechanics, and in fact ran the Imperial Observatory.[19] Their accurate methods allowed the Kangxi Emperor to successfully predict eclipses, one of his ritual duties. Other Jesuits functioned as court painters. The Jesuits in turn were impressed by the knowledge and intelligence of the Han Chinese Confucian scholar elite, and adapted to their ancient Chinese intellectual lifestyle.[20][21]

The Jesuits encountered a problem with their missionary work in China, and gradually developed and adopted a policy of accommodation on the issue of Chinese rites.[22] The Chinese scholar elite were attached to Confucianism, while Buddhism and Daoism were mostly practiced by the common people and lower aristocracy of this period. Despite this, all three provided the framework of both state and home life. Part of Confucian and Taoist practices involved veneration of one's ancestors.[3]

Besides the Jesuits, other religious orders such as the Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians started missionary work in China during the 17th century, often coming from the Spanish colony of the Philippines. Contrary to the Jesuits, they refused any adaptation to local customs and wished to apply in China the same tabula rasa principle they had applied in other places,[7] and were horrified by the practices of the Jesuits.[12]

They ignited a heated controversy and brought it to Rome.[23] They raised three main points of contention:[7]

- Determination of the Chinese word for "God", which was generally accepted as 天主 Tiānzhǔ (Lord of Heaven), while Jesuits were willing to allow Chinese Christians to use 天 Tiān (Heaven) or 上帝 Shàngdì (Lord Above / Supreme Emperor)

- Prohibition for Christians to participate in the season rites for Confucius.

- Prohibition for Christians of the use of tablets with the forbidden inscription "site of the soul", and to follow the Chinese rites for the ancestor worship.

In Rome, the Jesuits tried to argue that these "Chinese Rites" were social (rather than religious) ceremonies, and that converts should be allowed to continue to participate.[14][24]

The Jesuits argued that Chinese folk religion and offerings to the Emperor and departed ancestors were civil in nature and therefore not incompatible with Catholicism, while their opponents argued that these kinds of worship were an expression of native religion and thus incompatible with Catholic beliefs.[14][25]

Pope Clement XI's decree

Pope Clement XI condemned the Chinese rites and Confucian rituals, and outlawed any further discussion in 1704,[14] with the anti-rites decree Cum Deus optimus of November 20, 1704.[22] It forbade the use of "Tiān" and "Shàngdì", while approving Tiānzhǔ (‘Lord of Heaven’).[14]

In 1705, the Pope sent a Papal Legate to the Kangxi Emperor, to communicate to him the interdiction of Chinese rites. The mission, led by Charles-Thomas Maillard De Tournon, communicated the prohibition of Chinese rites in January 1707, but as a result was banished to Macao.[13][26]

Further, the Pope issued the 19 March 1715 Papal bull Ex illa die which officially condemned the Chinese rites:[13][27][28]

Pope Clement XI wishes to make the following facts permanently known to all the people in the world ...I. The West calls Deus [God] the creator of Heaven, Earth, and everything in the universe. Since the word Deus does not sound right in the Chinese language, the Westerners in China and Chinese converts to Catholicism have used the term "Heavenly Lord" (Tiānzhǔ) for many years. From now on such terms as "Heaven" [Tiān] and "Shàngdì" should not be used: Deus should be addressed as the Lord of Heaven, Earth, and everything in the universe. The tablet that bears the Chinese words "Reverence for Heaven" should not be allowed to hang inside a Catholic church and should be immediately taken down if already there.

II. The spring and autumn worship of Confucius, together with the worship of ancestors, is not allowed among Catholic converts. It is not allowed even though the converts appear in the ritual as bystanders, because to be a bystander in this ritual is as pagan as to participate in it actively.

III. Chinese officials and successful candidates in the metropolitan, provincial, or prefectural examinations, if they have been converted to Roman Catholicism, are not allowed to worship in Confucian temples on the first and fifteenth days of each month. The same prohibition is applicable to all the Chinese Catholics who, as officials, have recently arrived at their posts or who, as students, have recently passed the metropolitan, provincial, or prefectural examinations.

IV. No Chinese Catholics are allowed to worship ancestors in their familial temples.

V. Whether at home, in the cemetery, or during the time of a funeral, a Chinese Catholic is not allowed to perform the ritual of ancestor worship. He is not allowed to do so even if he is in company with non-Christians. Such a ritual is heathen in nature regardless of the circumstances.

Despite the above decisions, I have made it clear that other Chinese customs and traditions that can in no way be interpreted as heathen in nature should be allowed to continue among Chinese converts. The way the Chinese manage their households or govern their country should by no means be interfered with. As to exactly what customs should or should not be allowed to continue, the papal legate in China will make the necessary decisions. In the absence of the papal legate, the responsibility of making such decisions should rest with the head of the China mission and the Bishop of China. In short, customs and traditions that are not contradictory to Roman Catholicism will be allowed, while those that are clearly contradictory to it will not be tolerated under any circumstances.[29]

In 1742 Benedict XIV reiterated in his papal bull Ex quo singulari Clement XI's decree. Benedict demanded that missionaries in China take an oath forbidding them to discuss the issue again.[30]

Kangxi's ban

In the early 18th century, Rome's ensuing challenge to the Chinese Rites led to the expulsion of Catholic missionaries from China.[31]

In July 1706, the Papal Legate led by Charles-Thomas Maillard De Tournon irritated the Kangxi Emperor, and the emperor issued an order that all missionaries, in order to obtain an imperial permit (piao) to stay in China, would have to declare that they would follow ‘the rules of Matteo Ricci’.[22]

In 1721, the Kangxi Emperor disagreed with Clement's decree and banned Christian missions in China.[32][33] In the Decree of Kangxi, he stated,

Reading this proclamation, I have concluded that the Westerners are petty indeed. It is impossible to reason with them because they do not understand larger issues as we understand them in China. There is not a single Westerner versed in Chinese works, and their remarks are often incredible and ridiculous. To judge from this proclamation, their religion is no different from other small, bigoted sects of Buddhism or Taoism. I have never seen a document which contains so much nonsense. From now on, Westerners should not be allowed to preach in China, to avoid further trouble.[34]

Chinese converts were also involved in the controversy through letters of protest, books, pamphlets, etc.[22] The Controversy debate was most intense between a group of Christian literati and a Catholic Bishop (named Charles Maigrot de Crissey) in Fujian province, with the Chinese group of converts support the Jesuits and the bishop supported by less accommodating Iberian mendicants (Dominicans and Franciscans).[24]

The Qianlong Emperor's reinforcement

Although the Jesuits' defense of Christianity in China was still grounded in the accommodation policy first practiced by Matteo Ricci, it ended in failure in the eighteenth century: The persecution of Chinese Christians that began with his father's, the Yongzheng Emperor's 1724 proscription of the Heavenly Lord sect (Tianzhujiao, the name given Catholicism in China in that period)[35] steadily increased during the reign of Qianlong Emperor.[14] While the Qianlong Emperor appreciated and admired the Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione's artwork and western technologies, the emperor reinforced anti-Christian policies in 1737.[14]

Dissolution of Jesuits

Pope Clement XIV dissolved the Society of Jesuits in 1773, on the issue over Jesuit accommodation policy; in particular, the 1773 decree did not accept that Chinese Rites can be placed on equal footing with Europe and Christianity.[22]

Pope Pius XII's decision

The Rites controversy continued to hamper Church efforts to gain converts in China. In 1939, a few weeks after his election to the papacy, Pope Pius XII ordered the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples to relax certain aspects of Clement XI's and Benedict XIV's decrees.[36][37] After the Apostolic Vicars had received guarantees from the Manchukuo Government that confirmed the mere "civil" characteristics of the so-called "Chinese rites", the Holy See released, on December 8, 1939, a new decree, known as Plane Compertum, stating that:

- Catholics are permitted to be present at ceremonies in honor of Confucius in Confucian temples or in schools;

- Erection of an image of Confucius or tablet with his name on is permitted in Catholic schools.

- Catholic magistrates and students are permitted to passively attend public ceremonies which have the appearance of superstition.

- It is licit and unobjectionable for head inclinations and other manifestations of civil observance before the deceased or their images.

- The oath on the Chinese rites, which was prescribed by Benedict XIV, is not fully in accord with recent regulations and is superfluous.[38]

This meant that Chinese customs were no longer considered superstitious, but were an honourable way of esteeming one's relatives and therefore permitted by Catholic Christians.[39] Confucianism was also thus recognized as a philosophy and an integral part of Chinese culture rather than as a heathen religion in conflict with Catholicism. Shortly afterwards, in 1943, the Government of China established diplomatic relations with the Vatican. The Papal decree changed the ecclesiastical situation in China in an almost revolutionary way.[40] As the Church began to flourish, Pius XII established a local ecclesiastical hierarchy, and, in 1946, named Thomas Tien Ken-sin (Chinese: 田耕莘) SVD, then Apostolic Vicar of Qingdao, as the first Chinese national in the Sacred College of Cardinals[40] and later that year appointed him to the Archdiocese of Beijing.

See also

- History of Christian missions

- Religion in China

- Matteo Ricci

- Jesuit China missions

- Charles-Thomas Maillard de Tournon (1668–1710)

- List of Protestant theological seminaries in the People's Republic of China

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 Kuiper, Kathleen (31 Aug 2006). "Chinese Rites Controversy (Roman Catholicism) -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

The continuing controversy involved leading universities in Europe, was considered by eight popes and by the Kangxi emperor...

- ↑ Pacific Rim Report No. 32, February 2004, The Chinese Rites Controversy: A Long Lasting Controversy in Sino-Western Cultural History by Paul Rule, Ph.D.

- 1 2 3 George Minamiki (1985). The Chinese rites controversy: from its beginning to modern times. Loyola University Press. ISBN 978-0-8294-0457-9. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Edward G. Gray; Norman Fiering (2000). The Language Encounter in the Americas, 1492–1800: A Collection of Essays. Berghahn Books. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-57181-210-0. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Sacrosanctum concilium, para. 37. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ↑ Mantienne, pp.177-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Mantienne, p.178.

- ↑ Rule, Paul A. (2010). "What Were "The directives of Matteo Ricci" Regarding the Chinese Rites?" (PDF). Pacific Rim Report (54). Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- ↑ Mantienne, p.179.

- ↑ Missions, p. 4.

- ↑ Missions, p. 5. Original French: "Ne mettez aucun zèle, n'avancez aucun argument pour convaincre ces peuples de changer leurs rites, leurs coutumes et leur moeurs, à moins qu'ils ne soient évidemment contraires à la religion et à la morale. Quoi de plus absurde que de transporter chez les Chinois la france, l'Espagne, l'Italie, ou quelque autre pays d'Europe ? N'introduisez pas chez eux nos pays, mais la foi, cette foi qui ne repousse ni ne blesse les rites, ni les usages d'aucun peuple, pourvu qu'ils ne soient pas détestables, mais bien au contraire veut qu'on les garde et les protège."

- 1 2 3 p. 83.

- 1 2 3 Mantienne, p. 180.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jocelyn M. N. Marinescu (2008). Defending Christianity in China: The Jesuit Defense of Christianity in the "Lettres Edifiantes Et Curieuses" & "Ruijianlu" in Relation to the Yongzheng Proscription of 1724. ProQuest. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-0-549-59712-4. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Stephen Neill (1964). History of Christian Missions. Penguin Books. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Don Alvin Pittman (2001). Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu's Reforms. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-8248-2231-6. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Jesus in history, thought, and culture. 2. K - Z. ABC-CLIO. 2003. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-57607-856-3. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

... an Edict of Toleration, elevating Christiainity to the same status as Buddhism and Daoism.

- ↑ Zhidong Hao (28 February 2011). Macau: History and Society. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-988-8028-54-2. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph; Colin A. Ronan (20 June 1985). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China:. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31536-4.

- ↑ Udias, Agustin (1994). "Jesuit Astronomers in Beijing 1601–1805". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 35: 463. Bibcode:1994QJRAS..35..463U. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1958). Chinese astronomy and the Jesuit mission: an encounter of cultures. China Society occasional papers ; no. 10. China Society. OCLC 652232428.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stewart J. Brown; Timothy Tackett (2006). Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 7, Enlightenment, Reawakening and Revolution 1660-1815. Cambridge University Press. p. 463. ISBN 978-0-521-81605-2. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

Whereas from a missionary perspective the focus is on the sharp demarcation between the so-called ‘Jesuit’ and ‘Dominican’ positions, the role of the Chinese converts has been largely ignored. ‘Their involvement in the controversy through books, pamphlets, letters of protest etc. shows that they were truly imbedded in a Chinese society in which rites occupied an important place.’

- ↑ Mantienne, pp.177-80

- 1 2 D. E. Mungello (1 November 2012). The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4422-1977-9. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

Rites Controversy debate was most intense in Fujian province where an active group of Christian literati debated with a combative Catholic bishop named Charles Maigrot de Crissey (1652-1730). European missionaries divided largely on the lines of religious orders and nationalities. The Jesuits largely supported the Chinese while the Iberian mendicants (Dominicans and Franciscans) and secular priests were less accommodating.

- ↑ Donald Frederick Lach; Edwin J.. Van Kley (1998). East Asia. University of Chicago Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-226-46765-8. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Alfred Owen Aldridge (1997). Crosscurrents in the Literatures of Asia and the West: Essays in Honor of A. Owen Aldridge. University of Delaware Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-87413-639-5. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ 中國教會的禮儀之爭(1715年)

- ↑ 现代欧洲中心论者对莱布尼茨的抱怨

- ↑ Mantienne, pp.177-82

- ↑ James MacCaffrey (30 June 2004). The History Of The Catholic Church From The Renaissance To The French Revolution Volume 1. Kessinger Publishing. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4191-2406-8. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Peter Tze Ming Ng (3 February 2012). Chinese Christianity: An Interplay Between Global and Local Perspectives. BRILL. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-90-04-22574-9. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Marcia R. Ristaino (13 February 2008). The Jacquinot Safe Zone: Wartime Refugees in Shanghai. Stanford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8047-5793-5. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Robert Richmond Ellis (6 August 2012). They Need Nothing: Hispanic-Asian Encounters of the Colonial Period. University of Toronto Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-4426-4511-0. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Dun Jen Li (1969). China in transition, 1517-1911. Van Nostrand Reinhold. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Thomas H. Reilly, 2004, "The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: Rebellion and the Blasphemy of Empire," Seattle, WA:University of Washington Press, p. 43ff, 14ff, 150ff, ISBN 0295984309, see , accessed 18 April 2015.

- ↑ Matthew Bunson; Monsignor Timothy M Dolan (1 March 2004). OSV's Encyclopedia of Catholic History. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-59276-026-8. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ Christina Miu Bing Cheng (1999). Macau: A Cultural Janus. Hong Kong University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-962-209-486-4. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ↑ S.C.Prop. Fid., 8 Dec 1939, AAS 32-24. (The Sacred Congregation of Propaganda)

- ↑ Smit, pp.186–7

- 1 2 Smit, p.188

- References

- Mantienne, Frédéric 1999 Monseigneur Pigneau de Béhaine, Editions Eglises d'Asie, 128 Rue du Bac, Paris, ISSN 1275-6865 ISBN 2-914402-20-1,

- Missions étrangères de Paris. 350 ans au service du Christ 2008 Editeurs Malesherbes Publications, Paris ISBN 978-2-916828-10-7

- Smit, Jan Olav, 1951 Pope Pius XII, Burns Oates & Washburne, London&Dublin.

Further reading

- Jedin, Hubert, Kirchengeschichte Vol. VII, Herder Freiburg, 1988 (German)

- Metzler, Joseph, La Congregazione 'de Propaganda Fide' e lo sviluppo delle missioni cattoliche (secc. XVIII al XX), in Anuario de la Historia de la Iglesia, Año/Vol IX, Pamplona, 2000, pp. 145–54 (Italian)