Fort Dix

| Fort Dix | |

|---|---|

| Located near: Trenton, New Jersey | |

|

Combat Training at Army Support Activity, Fort Dix | |

| Coordinates | 40°01′09″N 74°31′22″W / 40.01917°N 74.52278°WCoordinates: 40°01′09″N 74°31′22″W / 40.01917°N 74.52278°W |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1917 |

| In use | 1917 – present |

| Army Support Activity Fort Dix | ||

|---|---|---|

| census-designated place | ||

| ||

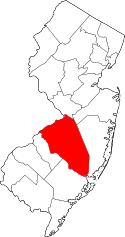

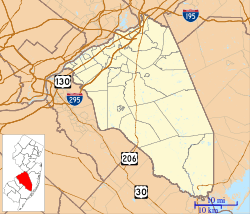

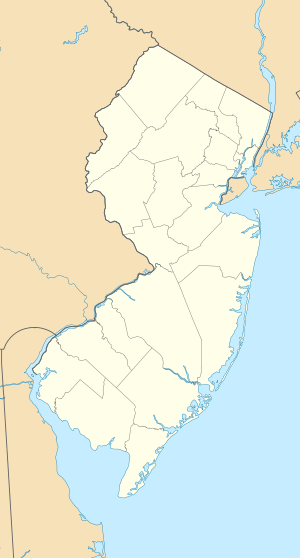

Army Support Activity Fort Dix  Army Support Activity Fort Dix  Army Support Activity Fort Dix Fort Dix CDP's location in Burlington County (Inset: Location of Burlington County in New Jersey). | ||

| Coordinates: 40°00′22″N 74°36′40″W / 40.006°N 74.611°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| State |

| |

| County | Burlington | |

| Township |

New Hanover Pemberton Springfield | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Total | 10.389 sq mi (26.909 km2) | |

| • Land | 10.262 sq mi (26.580 km2) | |

| • Water | 0.127 sq mi (0.329 km2) 1.22% | |

| Elevation[2] | 141 ft (43 m) | |

| Population (2010 Census)[3] | ||

| • Total | 7,716 | |

| • Density | 751.9/sq mi (290.3/km2) | |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) | |

| • Summer (DST) | Eastern (EDT) (UTC-4) | |

| ZIP code | 08640[4] | |

| Area code(s) | 609 | |

| FIPS code | 3424300[1][5][6] | |

| GNIS feature ID | 02389104[1][7] | |

Fort Dix, the common name for the Army Support Activity located at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, is a United States Army post. It is located approximately 16.1 miles (25.9 km) south-southeast of Trenton, New Jersey. Fort Dix is under the jurisdiction of the Army Installation Management Command. As of the 2010 United States Census, Fort Dix census-designated place (CDP) had a total population of 7,716,[3][8][9][10] of which 5,951 were in New Hanover Township, 1,765 were in Pemberton Township and none were in Springfield Township (though portions of the CDP are included there).[10]

Fort Dix, established in 1917, was consolidated with an adjoining U.S. Air Force and Navy facility to become part of Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (JB MDL) on 1 October 2009. However, it remains commonly known as "Fort Dix," "ASA Dix," or "Dix" as of 2015.

Overview

The supporting component at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst is the United States Air Force, and base operations are executed by the 87th Air Base Wing (87 ABW). The 87 ABW provides installation management to all of JBMDL while both the Navy and Army retain command and control of their mission, personnel, equipment and component-specific services. While the Joint Base has an assigned Deputy Joint Base Commander for both Army and Navy, neither the Navy nor the Army bases are subordinate to the Joint Base. Each are simply supported by the joint base in base operations such as utilities, child care centers, gyms, and other services, but each report through their own service-specific command chains and have their own commanders (the Navy a Captain and the Army a Colonel). sub.[11]

Fort Dix was established on 16 July 1917 as Camp Dix, named in honor of Major General John Adams Dix, a veteran of the War of 1812 and the American Civil War, and a former United States Senator, Secretary of the Treasury and Governor of New York.[12]

Dix has a history of mobilizing, training and demobilizing Soldiers from as early as World War I through April 2015 when Forts Bliss and Hood in Texas assumed full responsibility for that mission. In 1978, the first female recruits entered basic training at Fort Dix. In 1991, Dix trained Kuwaiti civilians in basic military skills so they could take part in their country's liberation.[12]

Dix ended its active Army training mission in 1991 due to Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommendations, which ended its command by a two-star general. Presently, it serves as a joint training site for all components and all services of the U.S. military and is commanded by an Army Colonel.

Units assigned

- Marine Aircraft Group 49[12]

- 99th Regional Support Command[12]

- 2d Brigade, 75th Division[12]

- USCG Atlantic Strike Team[12]

- U.S. Air Force Expeditionary Center[12]

- Military Entrance Processing Station[12]

- NCO Academy[12]

- Navy Operational Support Center[12]

- 174th Infantry Brigade[12]

- Fleet Logistics Squadron (VR-64)[12]

History

- See footnote[13]

Fort Dix is named for Major General John Adams Dix, a veteran of the War of 1812 and the Civil War. Construction began in June 1917. Camp Dix, as it was known at the time, was a training and staging ground for units during World War I. Though the camp was an embarkation camp for the New York Port of Embarkation it did not fall under the direct control of that command with the War Department retaining direct jurisdiction.[14] The camp became a demobilization center after the war. Between the World Wars, Camp Dix was a reception, training and discharge center for the Civilian Conservation Corps. Camp Dix became Fort Dix on March 8, 1939, and the installation became a permanent Army post. During and after World War II the fort served the same purpose as in the first World War. It served as a training and staging ground during the war and a demobilization center after the war.

On July 15, 1947, Fort Dix became a basic training center and the home of the 9th Infantry Division. In 1954, the 9th moved out and the 69th Infantry Division made the fort home until it was deactivated on March 16, 1956. During the Vietnam War rapid expansion took place. A mock Vietnam village was constructed and soldiers received Vietnam-specific training before being deployed. Since Vietnam, Fort Dix has sent soldiers to Operation Desert Shield, Desert Storm, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

U.S. Coast Guard site

The Atlantic Strike Team (AST) of the U.S. Coast Guard is based at Fort Dix. As part of the Department of Homeland Security, the AST is responsible for responding to oil pollution and hazardous materials release incidents to protect public health and the environment.[15][16]

Federal Correctional Institution

Fort Dix is also home to Fort Dix Federal Correctional Institution, the largest single federal prison in America. It is a low security installation for male inmates located within the military installation. As of November 19, 2009, it housed 4,310 inmates, and a minimum-security satellite camp housed an additional 426.[17] The coinage is mackerel, or macks; the inmates buy plastic pouches of it from the commissary and use it as commodity money.[18]

Mission realignment

Knowing that Fort Dix was on a base closure list the U.S. Air Force attempted to save the U.S. Army post during 1987. The USAF moved the Security Police Air Base Ground Defence school from Camp Bullis Texas to Dix in the fall of 1987. It was eventually realized that it was not cost effective to put 50-100 S.P. trainees on a commercial flight from San Antonio, Texas to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania every couple of weeks, so the school was later moved back to Camp Bullis Texas. Fort Dix was an early casualty of the first Base Realignment and Closure process in the early 1990s, losing the basic-training mission that had introduced new recruits to military life since 1917. But Fort Dix advocates attracted Army Reserve interest in keeping the 31,000-acre (13,000 ha) post as a training reservation. With the reserves, and millions for improvements, Fort Dix actually has grown again to employ 3,000. As many as 15,000 troops train there on weekends, and the post has been a major mobilization point for reserve and National Guard troops since the September 11, terror attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C.

Fort Dix has completed its realignment from an individual training center to a FORSCOM Power Projection Platform for the Northeastern United States under the command and control of the Army's Installation Management Command. Primary missions include a training, providing regional base operations support to on-post and off-post active component and U.S Army Reserve units, Soldiers, Families and Retirees. Fort Dix supported more than 1.1 million man-days of training in 1998. A daily average of more than 13,500 persons live or work within the garrison and its tenant organizations. Devens Reserve Force Training Area, MA is a sub-installation of the ASA.

2005 Realignments

In 2005, the United States Department of Defense announced that Fort Dix would be affected by a Base Realignment and Closure. For base operations support, it became part of shing Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, N.J. It was the first base of its kind in the United States and is the Department of Defense's only tri-service joint base. ASA, Ft Dix occupies and supports all training across 31,000 of the joint base's 42,000 acres.

Attack plots

1970

In 1970, the Weather Underground planned to detonate a nail bomb at a noncommissioned officers' dance at the base to "bring the war home" and "give the United States and the rest of the world a sense that this country was going to be completely unlivable if the United States continued in Vietnam." The plot failed the morning of the dance, when a bomb under construction exploded at the group's Greenwich Village, New York City townhouse, killing three members of the group.[19]

2007

| Wikinews has related news: Six arrested in plot against US army base in New Jersey |

On May 8, 2007, six individuals, mostly ethnic Albanian Muslims,[20] were arrested for plotting an attack against Fort Dix and the soldiers within. The men are believed to be Islamic radicals who may have been inspired by the ideologies of Al-Qaeda.[21] The men allegedly planned to storm the fort with automatic weapons in an attempt to kill as many soldiers as possible.[20] The men faced charges of conspiracy to kill U.S. soldiers.[22]

1969 stockade riot

On June 5, 1969, 250 men imprisoned in the military stockade for being AWOL, rioted in an effort to expose the unsanitary conditions.[23][24][25]

"Ultimate Weapon" monument

In 1957, during their leisure hours, Specialist 4 Steven Goodman, assisted by PFC Stuart Scherr, made a small clay model of a charging infantryman . Their tabletop model was spotted by a public relations officer who brought it to the attention of Deputy Post Commander Bruce Clarke, who suggested the construction of a larger statue to serve as a symbol of Fort Dix.[26] Goodman and Scherr, who had studied industrial arts together in New York City and were classified by the Army as illustrators, undertook the project under the management of Sergeant Major Bill Wright. Operating on a limited budget, and using old railroad track, Bondo and other available items, they created a 12-foot figure of a charging infantryman in full battle dress,[26] representing no particular race or ethnicity.[27]

By 1988, years of weather had taken a toll on the statue, and a restoration campaign raised over $100,000. Under the auspices of Goodman and the Fort Dix chapter of the Association of the United States Army, the statue was recast in bronze and its concrete base replaced by black granite.[28]

The statue stands 25 feet tall at the entrance to Infantry Park. Its inscription reads

- This monument is dedicated to

- the only indispensable instrument of war,

- The American Soldier---

- THE ULTIMATE WEAPON

- "If they are not there,

- you don't own it."

- 17 August 1990

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, Fort Dix had a total area of 10.389 square miles (26.909 km2), including 10.262 square miles (26.580 km2) of land and 0.127 square miles (0.329 km2) of water (1.22%).[1][29]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1970 | 26,290 | — | |

| 1980 | 14,297 | −45.6% | |

| 1990 | 10,205 | −28.6% | |

| 2000 | 7,464 | −26.9% | |

| 2010 | 7,716 | 3.4% | |

| Population sources: 1970-1980[30] 1990-2010[10] 2000[31] 2010[3] | |||

Census 2010

At the 2010 United States Census, there were 7,716 people, 784 households, and 590.4 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 751.9 per square mile (290.3/km2). There were 898 housing units at an average density of 87.5 per square mile (33.8/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 52.57% (4,056) White, 34.47% (2,660) Black or African American, 0.67% (52) Native American, 1.91% (147) Asian, 0.30% (23) Pacific Islander, 6.07% (468) from other races, and 4.02% (310) from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 21.47% (1,657) of the population.[3]

There were 784 households, of which 59.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 63.8% were married couples living together, 8.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.7% were non-families. 15.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 0.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.05 and the average family size was 3.56.[3]

In the CDP, 12.1% of the population were under the age of 18, 4.2% from 18 to 24, 50.2% from 25 to 44, 30.9% from 45 to 64, and 2.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.9 years. For every 100 females there were 522.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 757.5 males.[3]

Census 2000

As of the 2000 United States Census[5] there were 7,464 people, 843 households, and 714 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 663.9 people per square mile (256.4/km2). There were 1,106 housing units at an average density of 98.4 homes per square mile (38.0/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 58.4% White, 35.6% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.5% from other races, and 1.7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 22.8% of the population.[31]

There were 843 households, of which 63.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 75.2% were married couples living together, 6.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 15.3% were non-families. 14.7% of all households were made up of individuals and none had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.06 and the average family size was 3.39.[31]

In the CDP the population was spread out with 13.6% under the age of 18, 8.1% from 18 to 24, 62.1% from 25 to 44, 15.1% from 45 to 64, and 1.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 491.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 734.5 males.[31]

The median income for a household in the CDP was $41,397, and the median income for a family was $41,705. Males had a median income of $31,657 versus $22,024 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $10,543. About 2.5% of families and 3.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.2% of those under age 18 and none of those age 65 or over.[31]

Transportation

New Jersey Route 68 links Fort Dix to U.S. Route 206 near the latter's interchanges with the New Jersey Turnpike, U.S. Route 130 and Interstate 195. New Jersey Transit provides service to and from Philadelphia on the 317 route.[32]

Pop culture references

Fort Dix is the home base setting in Cinemaware's 1988 C64 and Nintendo video game Rocket Ranger; the game is based on an alternate World War II scenario, wherein the Nazis discover lunarium, which could allow them to win the war unless a young American scientist stops them.[33]

Fort Dix is mentioned several times in the TV show M*A*S*H as a former duty station of Colonel Potter, Commander of the 4077th MASH. Also, Company Clerk Maxwell Klinger lyingly told his mother he was stationed at Fort Dix so she wouldn't know he was serving in Korea.

See also

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Fort Dix has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Gazetteer of New Jersey Places, United States Census Bureau. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Fort Dix Census Designated Place, Geographic Names Information System. Accessed June 17, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data for Fort Dix CDP, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Look Up a ZIP Code for Fort Dix, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed June 17, 2013.

- 1 2 American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ↑ A Cure for the Common Codes: New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed June 17, 2013.

- ↑ US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ↑ GCT-PH1 - Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County -- County Subdivision and Place from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for Burlington County, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 8, 2013.

- ↑ 2006-2010 American Community Survey Geography for New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 8, 2013.

- 1 2 3 New Jersey: 2010 - Population and Housing Unit Counts - 2010 Census of Population and Housing (CPH-2-32), United States Census Bureau, p. III-5, August 2012. Accessed June 8, 2013.

- ↑ Mission Partners webpage. Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (JB MDL) official website. Accessed June 18, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst Dix". Newpreview.afnews.af.mil. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ↑ John Adams Dix and the history of Fort Dix webpage (ASA-Dix (U.S. Army Support Activity) official website). Accessed 2010-06-18.

- ↑ Huston, James A. (1966). The Sinews of War: Army Logistics 1775—1953. Army Historical Series. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. p. 346. LCCN 66060015. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Atlantic Strike Team (AST)". Uscg.mil. 2011-12-22. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ↑ Nash, Margo (July 2, 2000). "A Coast Guard Team Based (Where Else?) in the Pine Barrens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ "Federal Bureau of Prisons Weekly Population Report". Bop.gov. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ↑ Paumgarten, Nick (October 12, 2009). "The Secret Cycle". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

The coinage is mackerel, or macks; the inmates buy plastic pouches of it from the commissary.

- ↑ "The Weather Underground". TIME. October 7, 2008.

- 1 2 Russakoff, Dale; Eggen, Dan (2007-05-08). "Fort Dix Targeted in Terror Plot". Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ "6 held on terror conspiracy charges in N.J.". MSNBC. 2007-05-08. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ "6 Arrested In New Jersey Terror Plot". CBS. 2007-05-08. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ "150 Riot at Ft. Dix Stockade; Fires Set and Windows Broken". The New York Times. June 6, 1969.

Prisoners in the Fort Dix stockade set mattress fires, smashed windows and hurled footlockers, beds and other equipment tonight in what an Army spokesman characterized as a "disturbance."

- ↑ Crowell, Joan (1974). Fort Dix Stockade: Our Prison Camp Next Door. Berlin: Links. ISBN 0-8256-3035-5.

- ↑ Wallechinsky, David (1975). The People's Almanac. Garden City: Doubleday. p. 68. ISBN 0-385-04060-1.

- 1 2 "Stuart Scherr and Steven Goodman, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. Universal Match Corporation and United States of America, Defendants-Appellees., 417 F.2d 497 (2nd Cir. 1969)". Vlex.com. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ↑ "Historical Marker Database, The Ultimate Weapon". Hmdb.org. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ↑ The Ultimate Weapon - soldier's artwork stands for military tradition Archived June 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- ↑ Staff. 1980 Census of Population: Number of Inhabitants United States Summary, p. 1-140. United States Census Bureau, June 1983. Accessed June 17, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 DP-1 - Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 from the Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Fort Dix CDP, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 8, 2013.

- ↑ Burlington County Bus / Rail Connections, New Jersey Transit, backed up by the Internet Archive as of June 26, 2010. Accessed June 17, 2013.

- ↑ Farrell, Andrew. "Future's back to good old days", The Sydney Morning Herald, October 31, 1988. Accessed June 17, 2013. "Cinemaware's new game, Rocket Ranger, brings back the memories and pays tribute to old-time greats... Commands can only be issued from home base in Fort Dix, New Jersey."

- ↑ Climate Summary for Fort Dix

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Dix. |

- Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst official website

- ASA - Dix official website (U.S. Army Support Activity)

- Fort Dix Command Chaplain Section. Army Support Activity–Dix (ASA-Dix) official website

- IMCOM Atlantic Region official website (U.S. Army Installation Management Command)

- Details on the Ultimate Weapon monument from the Fort Dix website

- Global Security details of history, area, military units, etc.